Introduction to Mead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Served Nightly 6-11Pm Enlightenment . Wines . Meadery . Food Bottles to Go

SEASONAL ARCHIVE ELCOME. TO. HONEY’S, OUR RECENT RELEASES RARE MEADS FROM THE EW VAULT THE . T AST I N G . R OOM AND.COCKTAIL.BAR.FOR ENLIGHTENMENT W DAGGER ENLIGHTE NME NT. WINE S W* GLASS: 16 (2.5OZ) BOTTLE: 60 NEW..YORK CITY’S..FIRST..MEADERY. *NE NOUGHT MOST OF .WHAT .WE. PRODUCE YOU GLASS: 10 BOTTLE: 35 BOTANICAL CHERRY MEAD WITH FIR HEMLOCK, CHAMOMILE AND YARROW. OUR SHOW MEAD, SPONTANEOUSLY FERMENTED CAN DRINK BY THE GLASS AS WELL AS AROMATIC DRY AND TANNIC DRY FROM WILDFLOWER HONEY AND WELL WATER- , . PURCHASE IN BOTTLES TO GO. AGED IN BARRELS, DRY AND COMPLEX 12.5%ABV, 375 ML BOTTLE 2018 MEAD IS A KIND OF WINE, FERMENTED 12.5%ABV, 750 ML 2019 FROM HONEY, HERBS AND FRUITS RTR (RAISE THE ROOF) W* GLASS: N/A BOTTLE: 60 RATHER.THAN.GRAPES. THROUGH *NE NIGHT EYES LIGHTLY SPARKLING SOUR MEAD FERMENTED IN OAK GLASS: 12 BOTTLE: 40 THE WINDOW BEHIND THE BAR, FROM LACTIC BACTERIA, WILD YEAST, WELL WATER AND YOU CAN VIEW OUR MEADERY AND SPARKLING MEAD MADE FROM APPLES, APPLE BLOSSOM HONEY. BOTTLE CONDITIONED IN THE MAY EVEN FIND US WORKING ON A CHERRIES, ROSEHIPS AND SUMAC. ANCESTRAL METHOD.13%ABV, 750 ML 2018 BONE DRY AND FRUITY. NEW RELEASE. 12.5%ABV, 750 ML 2019 ENLIGHTENMENTWINES IS A NATURAL * NEW MEADERY..ALL.OUR.INGREDIENTS * MEMENTO MORI . BOTTLES TO GO WINES ARE.LOCALLY.SOURCED.OR.FORAGED. GLASS: 9 (2.5OZ) BOTTLE: 35 DANDELION MEAD, A HISTORICAL NEW ENGLAND * W E EMB R A CE SPONTA NEOUS NEW 2019 NOUGHT 750ml 25 TONIC AND DIGESTIF MADE FROM FORAGED * 2019 NIGHT EYES 750ml 30 FERMENTATION, BARREL AGING W* DANDELION BLOSSOMS AND WILDFLOWER HONEY. -

Chaucer's Presspak.Pub

Our History established 1964 1970’s label 1979: LAWRENCE BARGETTO in the vineyard The CHAUCER’S dessert wine story begins on the banks of Soquel “Her mouth was sweet as Mead or Creek, California. In 1964, winery president, Lawrence Bargetto, saw honey say a hand of apples lying an opportunity to create a new style of dessert wine made from fresh, in the hay” locally-grown fruit in Santa Cruz County. —THE MILLERS TALE With an abundant supply of local plums, Lawrence decided to make “They fetched him first the sweetest wine from the Santa Rosa Plums growing on the winery property. wine. Then Mead in mazers they combine” Using the winemaking skills he learned from his father, he picked the —TALE OF SIR TOPAZ fresh plums into 40 lb. lug boxes and dumped them into the empty W open-top redwood fermentation tanks. Since it was summer, the fer- The above passages were taken from mentation tanks were empty and could be used for this new dessert Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, wine experiment. a great literary achievement filled with rich images of Medieval life in Merry ole’ England. Immediately after the fermentation began, the cellars were filled with the delicate and sensuous aromas of the Santa Rosa Plum. Lawrence Throughout the rhyming tales one had not smelled this aroma in the cellars before and he was exhilarated finds Mead to be enjoyed by com- moner and royalty alike. with the possibilities. After finishing the fermentation, clarification, stabilization and sweet- ening, he bottled the wine in clear glass to highlight the alluring color of crimson. -

View Shelf Talker

PROPERTY OF PACIFIC EDGE IMPORTS, AGOURA HILLS, CA PROPERTY OF PACIFIC EDGE IMPORTS, AGOURA HILLS, CA Lindisfarne Meade Lindisfarne Meade Lindisfarne Mead is a unique alcoholic fortified Lindisfarne Mead is a unique alcoholic fortified wine manufactured on the Holy Island of wine manufactured on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast. Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast. The honey which is used in the production of The honey which is used in the production of Lindisfarne Mead is drawn from the four corners Lindisfarne Mead is drawn from the four corners of the world and here on the island, it is vatted of the world and here on the island, it is vatted with fermented grape juice, honey, herbs and pure with fermented grape juice, honey, herbs and pure natural water of an artesian well and fortified with natural water of an artesian well and fortified with fine spirits to produce this unique drink. fine spirits to produce this unique drink. PROPERTY OF PACIFIC EDGE IMPORTS, AGOURA HILLS, CA PROPERTY OF PACIFIC EDGE IMPORTS, AGOURA HILLS, CA Lindisfarne Meade Lindisfarne Meade Lindisfarne Mead is a unique alcoholic fortified Lindisfarne Mead is a unique alcoholic fortified wine manufactured on the Holy Island of wine manufactured on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast. Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast. The honey which is used in the production of The honey which is used in the production of Lindisfarne Mead is drawn from the four corners Lindisfarne Mead is drawn from the four corners of the world and here on the island, it is vatted of the world and here on the island, it is vatted with fermented grape juice, honey, herbs and pure with fermented grape juice, honey, herbs and pure natural water of an artesian well and fortified with natural water of an artesian well and fortified with fine spirits to produce this unique drink. -

Wine List Denali Spirits Cocktails Handcrafted

WINE LIST DENALI SPIRITS COCKTAILS Mead by Twisted Mule Denali Spirits Vodka, our handcrafted ginger soda and fresh Denali Brewing squeezed lime. Served in a copper mug. 10 Razzery Bloody Mary A fruity, earthy nose with a Denali Spirits Vodka, Demitri’s Bloody Mary mix, tomato juice, fresh combination of raspberries, sour squeezed lemon and a Cajun spice seasoned rim. Garnished with cherries and apples. soprasetta, pepperjack cheese and a pepperoncini. 11 Glass 9 | Bottle 34 Denali Spirits Martini Mead by Chilled Denali Spirits vodka or gin, with a dry vermouth wash and olive garnish. 13 Celestial Meads Negroni Tentaçao Denali Spirits Gin, Campari, sweet vermouth and fresh orange zest. A blend of Solera tawny port and Served on the rocks. 12 sorghum honey mead. Glass 8 | Bottle 28 Denali Spirits Cocktail Special Oh Pear The Denali Spirits distillery is always trying something new... A semi sweet melomel made with Ask your server what’s shaking! orange blossom honey and pears. Glass 8 | Bottle 28 Tutti Frutti HANDCRAFTED COCKTAILS A sweet melomel made with blackberry blossom honey and six Perfect Scratch Margarita different fruits. Tequila, Cointreau, simple syrup and lime, Glass 8 | Bottle 28 lemon and orange juice fresh squeezed to order. 12 Cadillac Margarita with Grand Marnier 14 Mead Spritzer Your choice of mead with a Old Fashioned splash of soda water. 9 Your choice of whiskey, simple syrup, bitters, fresh orange zest and a Luxardo cherry, stirred and served over ice. Red Wine Price varies with choice of spirit House Malbec Glass 6 Irish Coffee House Cabernet Glass 6 Jameson Irish Whiskey, Kaladi Bros. -

Mead Variants

Mead Variants (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Tr6jniak - A Polish mead, made using two units of water for each unit of honey Acerglyn - A mead made with honey and maple syrup. Balche - A native Mexican version of mead. Black mead - A name sometimes given to the blend of honey and black currants. Bochet - A mead where the honey is caramelized or burned separately before adding the water. Yields toffee, chocolate, and marshmallow flavors. Braggot - Also called bracket or brackett. Originally brewed with honey and hops, later with honey and malt - with or without hops added. Welsh origin (bragawd). Capsicumel - A mead flavored with chili peppers. Chouchenn - A kind of mead made in Brittany. Cyser - A blend of honey and apple juice fermented together; see also cider. Czw5rniak (TSG) - A Polish mead, made using three units of water for each unit of honey Dandaghare - A mead from Nepal, combines honey with Himalayan herbs and spices. lt has been brewed since 1972 in the city of Pokhara. Dw6jniak(Tsc) - A Polish mead, made using equal amounts of water and honey Great mead - Any mead that is intended to be aged several years. The designation is meant to distinguish this type of mead from "short mead" (see below). Gverc or Medovina - Croatian mead prepared in Samobor and many other places. The word "gverc" or "gvirc' is from the German "Gewiirze" and refers to various spices added to mead. Hydromet - Literally "water-honey" in Greek. lt is also the French name for mead. (Compare with the Catalan hidromel, Galician aiguamel, Portuguese hidromel, ltalian idromele, and Spanish hidromiel and aguamiel). -

Regulation (Eu) 2019/ 787 of the European Parliament

17.5.2019 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 130/1 I (Legislative acts) REGULATIONS REGULATION (EU) 2019/787 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 17 April 2019 on the definition, description, presentation and labelling of spirit drinks, the use of the names of spirit drinks in the presentation and labelling of other foodstuffs, the protection of geographical indications for spirit drinks, the use of ethyl alcohol and distillates of agricultural origin in alcoholic beverages, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 110/2008 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Articles 43(2) and 114(1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the European Commission, After transmission of the draft legislative act to the national parliaments, Having regard to the opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee (1), Acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure (2), Whereas: (1) Regulation (EC) No 110/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council (3) has proved successful in regulating the spirit drinks sector. However, in the light of recent experience and technological innovation, market developments and evolving consumer expectations, it is necessary to update the rules on the definition, description, presentation and labelling of spirit drinks and to review the ways in which geographical indications for spirit drinks are registered and protected. (2) The rules applicable to spirit drinks should contribute to attaining a high level of consumer protection, removing information asymmetry, preventing deceptive practices and attaining market transparency and fair competition. -

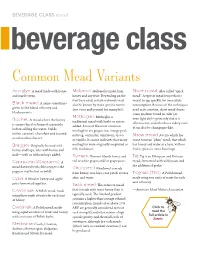

Common Mead Variants Acerglyn: a Mead Made with Honey Melomel: Melomel Is Made from Short Mead: Also Called “Quick and Maple Syrup

BEVERAGE CLASS mead beverage class Common Mead Variants Acerglyn: A mead made with honey Melomel: Melomel is made from Short mead: Also called “quick and maple syrup. honey and any fruit. Depending on the mead.” A type of mead recipe that is fruit base used, certain melomels may meant to age quickly, for immediate Black mead: A name sometimes also be known by more specific names consumption. Because of the techniques given to the blend of honey and (see cyser and pyment for examples). used in its creation, short mead shares blackcurrants. some qualities found in cider (or Metheglin: Metheglin is Bochet: even light ale)—primarily that it is A mead where the honey traditional mead with herbs or spices is caramelized or burned separately effervescent, and often has a cidery taste. added. Some of the most common It can also be champagne-like. before adding the water. Yields metheglins are ginger, tea, orange peel, toffee, caramel, chocolate and toasted nutmeg, coriander, cinnamon, cloves Show mead: A term which has marshmallow flavors. or vanilla. Its name indicates that many come to mean “plain” mead, that which Braggot: Originally brewed with metheglins were originally employed as has honey and water as a base, with no honey and hops, later with honey and folk medicines. fruits, spices or extra flavorings. malt—with or without hops added. Pyment: Pyment blends honey and Tej: Tej is an Ethiopian and Eritrean Capsicumel/Capsumel: A red or white grapes and/or grape juice. mead, fermented with wild yeasts and the addition of gesho. mead flavored with chile peppers (the Rhodomel: Rhodomel is made peppers may be hot or mild). -

THE MAGAZINE of the GERMAN WINE INSTITUTE Ochsle

THE MAGAZINE OF THE GERMAN WINE INSTITUTE oCHSLE TRAVEL & ENJOYMENT EXPERIENCE WINE WINE KNOWLEDGE OVERVIEW OF ALL ALL YOU NEED TO GERMAN WINE TIPS FOR KNOW FROM AHR GROWING REGIONS THE ACTIVE TO ZELLERTAL Wine is the nightingale of drinks. Voltaire David Schildknecht, The Wine Advocate, USA Advocate, The Wine David Schildknecht, this to us. has revealed generations of vintners which of Riesling and the work several greatness I do indeed feel deep humility in view of the German wine is very popular in my country today, as it is all over the world. German wine is very popular in my country today, Riesling especially so,even in Italy is seen as the finest and most which durable white wine in the world. Gian Luca Mazella, wine journalist, Rome Wine is bottled poetry. Robert Louis Stevenson Paul Grieco, Restaurant Hearth, New York Paul Grieco,Hearth, New Restaurant German wine! in America… Thank god for produced the antithesis of those German wines are German wines, whether it is the inimitable Riesling or the deli- cate Pinot Noir, are enjoyable and wonderful with all types of food with their refreshing acidity and focused, linear style. Jeannie Cho Lee, MW, Hongkong A miracle has happened in Germany. A generation ago there were good German wines but you had to search hard to find some. Today they are available in abundance in every price range. Stuart Pigott, English author and wine critic Consumers’ and opinion makers’ fanaticism for dry wine and against the threat of global gustatory uni- formity, gives German vintners an opportunity to flourish with that dazzling stylistic diversity of which they are uniquely capable. -

Volatile Profile of Mead Fermenting Blossom Honey and Honeydew

molecules Article Volatile Profile of Mead Fermenting Blossom Honey and Honeydew Honey with or without Ribes nigrum Giulia Chitarrini 1 , Luca Debiasi 1, Mary Stuffer 1,2, Eva Ueberegger 1, Egon Zehetner 2, Henry Jaeger 2, Peter Robatscher 1 and Lorenza Conterno 1,* 1 Laimburg Research Centre, Ora (BZ), 39040 Auer, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (L.D.); mary.stuff[email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (E.U.); [email protected] (P.R.) 2 Institute of Food Technology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (E.Z.); [email protected] (H.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0471969591 Academic Editor: Eugenio Aprea Received: 27 March 2020; Accepted: 11 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Abstract: Mead is a not very diffused alcoholic beverage and is obtained by fermentation of honey and water. Despite its very long tradition, little information is available on the relation between the ingredient used during fermentation and the aromatic characteristics of the fermented beverage outcome. In order to provide further information, multi-floral blossom honey and a forest honeydew honey with and without the addition of black currant during fermentation were used to prepare four different honey wines to be compared for their volatile organic compound content. Fermentation was monitored, and the total phenolic content (Folin–Ciocalteu), volatile organic compounds (HS-SPME-GC-MS), together with a sensory evaluation on the overall quality (44 nontrained panelists) were measured for all products at the end of fermentation. -

Wine and Spirit Drinks Act Promulgated, State Gazette No

Wine and Spirit Drinks Act Promulgated, State Gazette No. 86/1.10.1999, effective 2.01.2000, amended and supplemented, SG No. 56/7.06.2002, SG No. 16/27.02.2004, supplemented, SG No. 108/10.12.2004, effective 1.01.2005, amended, SG No. 113/28.12.2004, effective 1.01.2005, SG No. 99/9.12.2005, effective 10.06.2006, SG No.1 OS/29.12.2005, effective 1.01.2006 Chapter One GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1. (1) (Supplemented, SG No. 16/2004) This Act establishes the terms and the procedure for the production, obtaining, processing, trade and control of grapes for wine-making, wines, grape-based and wine-based products, and of spirit drinks, as well as the management and control of vine-growing and wine production potential. (2) (New, SG No. 16/2004) The provisions of this Act shall apply to the products listed in Annex 1 hereto. (3) (Renumbered from Paragraph (2), SG No. 16/2004) This Act is intended to create conditions for rehabilitation and development of the vine and wine sector, for improvement of the quality of wines, grape based or wine-based drinks and products, through introduction of a system of measures regulating the processes of the obtaining, production and trade thereof. (4) (Renumbered from Paragraph (3) and amended, SG No. 16/2004) The Minister of Agriculture and Forestry, jointly with the National Vine and Wine Chamber, shall prepare a National Strategy for Development of Vine growing and Wine-making in Bulgaria and shall lay the said Strategy before the Council of Ministers for approval. -

Let's Talk About Mead and Cider…

Let’s talk about mead and cider… Balance – this is something every brewer is familiar with. Two or more aspects of the beer, in harmony. They don’t have to necessarily be equal, but must complement each other – that IPA has way more hops than malt, but without ANY malt, it wouldn’t be balanced. So each style and each individual creation has their own balanced points. There’s more than two aspects to balance in mead, and there isn’t only one right answer. The legs of the chair you’re on can be balanced at a shorter or longer length, and a slight imbalance will barely be noticeable. Balance in mead and cider Sweetness – generally a function of FG, with higher FG being sweeter, however some honeys (meadowfoam/tupelo) will remain sweet at a fairly low FG. Can be from residual sugar or back-sweetening Acidity – low pH, sometimes tartness or sourness. Balances well with sweetness, though too much of each and you’ve got a Sweet-Tart – Good in candy, not a great combination in most meads. Not enough acid, and you’ve got a “flabby” uninteresting, structureless beverage like the blackberry mead I served last time. Alcohol – this tends to balance sweetness and increases bitterness. Body gets bigger with more alcohol but IMO the perceived body gets lower. Tannin – these can be hard (bitter) or soft (astringent) and are perhaps most easily noticed in wine or over- brewed tea. They have a drying aftertaste, and increase perception of dryness in mead/cider, and increase body. Other than grapes, some apples have a lot of tannins, but honey has little. -

Guide to Mead Making a Moremanual !™ by Shea A.J

Guide to Mead Making A MoreManual !™ by Shea A.J. Comfort www.MoreBeer.com 1–800-600–0033 www.MoreWinemaking.com 1–800-823–0010 Hello, and welcome to MoreFlavor!’s Mead Making Manual. I mean that all of the usual techniques that one is hoping to The goal of this manual is to give a complete, yet, easily acces- employ for a quality white wine apply here, as well, namely: sible overview of what is needed to make great mead the first • yeast strain selection (they all have quite different quali- time out. We will begin by taking a look at some important ties) technical aspects that are unique to mead making, because • proper care and feeding of the yeast (extremely impor- this will show us what is needed for a successful fermentation. tant for a mead, more later) From there, we will look at a simple, yet elegant solution that • pH & TA% monitoring (also very critical for a successful incorporates these considerations into a straight-foreward, fermentation) step-by-step process for preparing the mead for fermentation • controlling the fermentation’s temperature, if possible that does not require heating and is done in around 30 min- (55° F to 75° F) utes! Finally, we will look at how to make different styles of • complete absence of oxygen after the primary fermenta- mead, such as sparkling mead and how to incorporate fruit. tion has completed Every so often in life we come across something that requires very little effort on our part, yet winds up being extremely re- Understanding and incorporating each of these above ele- warding and mead making is one of those things! Enjoy the ments into your meadmaking as a whole is important because process and welcome to mead making! they are the very steps needed to avoid a prolonged, stuck fer- mentation, avoid hydrogen sulphide problems, and to ensure Let’s Begin With A Quick Word About (as well as to preserve) the best, possible flavour and aroma Honey Quality And It’s Handling profile for your meads.