Complete and Worth Nothing When Fallow 'Because It Is Detailed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maurice Warwick Beresford 1920–2005

02 Beresford 1722 13/11/09 13:19 Page 18 MAURICE BERESFORD Zygmunt Bauman University of Leeds 02 Beresford 1722 13/11/09 13:19 Page 19 Maurice Warwick Beresford 1920–2005 MAURICE BERESFORD, economic and social historian born in Sutton Coldfield, Warwickshire on 6 February 1920, was the only child of Harry Bertram Beresford and Nora Elizabeth Beresford (née Jefferies). Both sides of the family had their roots in the Birmingham area. Presumably his parents met when they were both living in Handsworth and working in a chemist’s company; on their marriage certificate of 1915 his father is described as a despatch clerk and his mother as an assistant. By the time Maurice was born his father had risen to the rank of ‘Departmental Manager in Wholesale Druggists Warehouse’, a position he continued to hold until his early death aged 46 in 1934. Maurice continued to live with his widowed mother in the Sutton Coldfield area and later in Yorkshire until her death in Adel, Leeds, aged 79, in 1966. As the family was of modest financial means, the more so after his father’s death, all of Maurice’s schooling was local to Sutton Coldfield (Boldmere Council Infants, 1925–6: Green Lanes Senior Boys, 1926–30: Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School, 1930–8). At Bishop Vesey’s, as he was later to recount,1 two masters in particular influenced the course of his life; William Roberts, a ‘stimulating history master’ and William Sutton— ‘a terrifying and rigorous geography master who made map reading as natural and interesting as reading a novel or a play’. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 P1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647 Mm Scale: 100%

British Sky Broadcasting Group plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 p1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647mm Scale: 100% Table of contents Chairman’s statement 3 Directors’ report – review of the business Chief Executive Officer’s statement 4 Our performance 6 The business, its objectives and its strategy 8 Corporate responsibility 23 People 25 Principal risks and uncertainties 27 Government regulation 30 Directors’ report – financial review Introduction 39 Financial and operating review 40 Property 49 Directors’ report – governance Board of Directors and senior management 50 Corporate governance report 52 Report on Directors’ remuneration 58 Other governance and statutory disclosures 67 Consolidated financial statements Statement of Directors’ responsibility 69 Auditors’ report 70 Consolidated financial statements 71 Group financial record 119 Shareholder information 121 Glossary of terms 130 Form 20-F cross reference guide 132 This constitutes the Annual Report of British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (the ‘‘Company’’) in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (‘‘IFRS’’) and with those parts of the Companies Act 2006 applicable to companies reporting under IFRS and is dated 29 July 2009. This document also contains information set out within the Company’s Annual Report to be filed on Form 20-F in accordance with the requirements of the United States (“US”) Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”). However, this information may be updated or supplemented at the time of filing of that document with the SEC or later amended if necessary. This Annual Report makes references to various Company websites. The information on our websites shall not be deemed to be part of, or incorporated by reference into, this Annual Report. -

Blauen Folker

Im Kalender vermerkt? Ausgabe 5/6.2020 ISSN 1435-9634 Unsere blauen Termin- und Postvertriebsstück: Serviceseiten K45876 Webseiten für Termine 04 Folker Corona Angebote 16 Wundertütenschätze CD‘S 18 Minnesang zur Popakademie 19 d Etcetera I 21 Wir suchten Helfer 23 Womex goes digital 2020 24 (se) Ausgerechnet die Gema 25 Die blauen Sicherung des Kulturlebens 26 Wirrwarr um Soforthilfen 27 Ja, ich bin systemrelevant 29 Gaeltacht Irland Reisen 30 Folker- 23 Jahre Folker 31 Irish Folk Festival 2021 32 Redaktionsschluss für die Serviceseiten der Ausgabe 1/21 ist spät. am 10.12.2020. „Termin“- und Oder schon vorher, wenn wir euch online informieren sollen/wollen. Serviceseiten Gerne auch online: www.termine-folk-lied-weltmusik.de Moers, Mitte September 2020 und zu denen die (quasi öffentlich-rechtliche) Bundessteuerberaterkammer fast jede Woche ein Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Update von Fragen und Antworten veröffentlichen musste, weil die Damen und Herren BeamtenInnen in Was sind das für Zeiten! den vielen beteiligten Ministerien (von den Politikern Kann es sein, dass sie so oder ähnlich bleiben – für wollen wir nicht reden) fast keine Vorschrift länger? auslegungseindeutig oder rechtssicher hingekriegt Corona scheint unser Leben zu beherrschen, das der haben? Das muss man sich mal vorstellen: Da Medien ohnehin. Deshalb halten „Frust, Wut und wurden Anträge (seit 7. Juli) abgegeben – und die Fassungslosigkeit“ an (Siehe letzte „Blaue Seiten“, spezifizierten Auslegungskriterien wurden erst Heft 3+4/2020, und die verkümmerten Terminseiten hinterher veröffentlicht, Stück für Stück, auf zuletzt in der Heftmitte). weiteren 50 Seiten, gut 150 Einzelpunkte. Deshalb „Für viele sogenannte Soloselbstständigen und gibt es einen Beitrag (in den „Blauen Seiten“) mit Freiberufler bleibt es ein Hohn, wenn Olaf Scholz dem Titel „Wirrwarr bei den Hilfen“. -

Walking in Steeple Bumpstead

Birdbrook a courtyard house of about 1500. It 2 The small village of Birdbrook, was built for the Gent family, although Steeple Bumpstead Highlights with a population of around 300, is takes its name from the Norman ‘Le thought to be named such due to the Moigne’ family, who were there in 1254 Steeple Bumpstead 1915, shot by German firing squad for brook that passes through the parish. and owned much land in the area. 1 As you walk around Steeple helping allied soldiers escape. The Old The quaint and beautiful village The house was passed down from Bumpstead, there are several features Vicarage, now a private residence, has church, St Augustine’s, is one of the Major-General Cecil Robert St John Ives that give a nod to the village’s ancient a plaque that commemorates her time oldest churches in the county. The to his grandson, Ivar Bryce. There is history, and people of the past. in Steeple Bumpstead. There is also a a long-standing equestrian history to The Moot Hall, at the cross-roads in plaque dedicated to her memory in St The Church of St Augustine the house. It was used as a residential the middle of the village, is believed Mary’s Parish Church, and there is a riding school in and around 1949, with to have been built sometime in the road named after her in the village – courses in dressage and show jumping, 1570’s and is the earliest known school Edith Cavell Way. and then became a stud farm in 1955. -

Channel Guide August 2018

CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2018 KEY HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU HAVE 1 PLAYER PREMIUM CHANNELS 1. Match your ENTERTAINMENT package 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 MORE to the column 100 Virgin Media Previews 3 M+ 101 BBC One If there’s a tick 4 MIX 2. 102 BBC Two in your column, 103 ITV 5 FUN you get that 104 Channel 4 6 FULL HOUSE channel ENTERTAINMENT SPORT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 100 Virgin Media Previews 501 Sky Sports Main Event 101 BBC One HD 102 BBC Two 502 Sky Sports Premier 103 ITV League HD 104 Channel 4 503 Sky Sports Football HD 105 Channel 5 504 Sky Sports Cricket HD 106 E4 505 Sky Sports Golf HD 107 BBC Four 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 108 BBC One HD 507 Sky Sports Action HD 109 Sky One HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 110 Sky One 509 Sky Sports News HD 111 Sky Living HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 112 Sky Living 511 Sky Sports Main Event 113 ITV HD 512 Sky Sports Premier 114 ITV +1 League 115 ITV2 513 Sky Sports Football 116 ITV2 +1 514 Sky Sports Cricket 117 ITV3 515 Sky Sports Golf 118 ITV4 516 Sky Sports F1® 119 ITVBe 517 Sky Sports Action 120 ITVBe +1 518 Sky Sports Arena 121 Sky Two 519 Sky Sports News 122 Sky Arts 520 Sky Sports Mix 123 Pick 521 Eurosport 1 HD 132 Comedy Central 522 Eurosport 2 HD 133 Comedy Central +1 523 Eurosport 1 134 MTV 524 Eurosport 2 135 SYFY 526 MUTV 136 SYFY +1 527 BT Sport 1 HD 137 Universal TV 528 BT Sport 2 HD 138 Universal -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

For Sale Or to Let

FOR SALE OR TO LET Part Barn at Birdbrook Hall Farm Fell Road, Birdbrook, Essex, CO9 4BJ Haverhill 4.5 miles, Steeple Bumpstead 3 miles, Braintree 16 miles, Cambridge 23 miles Single span of a Dutch barn Available to let for a variety of alternative uses (subject to planning permission) Approximately: 237m2 (2,548 sq ft2) Viewing Strictly by appointment Please call to discuss your requirements. Land Partners LLP, Lyons Hall Business Park, Lyons Hall Road, Braintree, Essex, CM7 9SH Tel: 01376 328297 Email: [email protected] Location & Description: Birdbrook Hall Farm lies on the northern edge of the rural village of Birdbrook. Birdbrook is approximately 4.5 miles from the centre of Haverhill and 16 miles from Braintree. The building is accessed from Fell Road through a farm-gate and the space to be let comprises part of a 3 span Dutch barn. [NB. It is only the span closest to the road which is available, as identified on the plan below] The space to be let measures 8.8 metres by 26.9 metres and is of steel portal frame construction with part concrete block walls to a height of approximately 1.6 metres as the external wall, clad with corrugated iron above. The roof is curved corrugated iron and there is a concrete floor throughout. The space is partially divided from the remainder of the building by a wooden grain-wall partition to a height of c. 1.6 metres along 5 of the 6 bays of the barn but is open above this height. The front of the space is open. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

At My Table 12:00 Football Focus 13:00 BBC News

SATURDAY 9TH DECEMBER 06:00 Breakfast All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 09:25 Saturday Morning with James Martin 09:50 Black-ish 06:00 Forces News 11:30 Nigella: At My Table 11:20 Gino's Italian Coastal Escape 10:10 Made in Chelsea 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 12:00 Football Focus 11:45 The Hungry Sailors 11:05 The Real Housewives of Cheshire 07:00 Flying Through Time 13:00 BBC News 12:45 Thunderbirds Are Go 11:55 Funniest Falls, Fails & Flops 07:30 The Aviators 13:15 Snooker: UK Championship 2017 13:10 ITV News 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 08:00 Sea Power 16:30 Final Score 13:20 The X Factor: Finals 13:05 Shortlist 08:30 America's WWII 17:15 Len Goodman's Partners in Rhyme 15:00 Endeavour 13:10 Baby Daddy 09:00 America's WWII 17:45 BBC News 17:00 The Chase 13:35 Baby Daddy 09:30 America's WWII 17:55 BBC London News 18:00 Paul O'Grady: For the Love of Dogs 14:00 The Big Bang Theory 10:00 The Forces Sports Show 18:00 Pointless Celebrities 18:25 ITV News London 14:20 The Big Bang Theory 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:45 Strictly Come Dancing 18:35 ITV News 14:40 The Gadget Show 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 20:20 Michael McIntyre's Big Show 18:50 You've Been Framed! 15:30 Tamara's World 11:30 Hogan's Heroes Family entertainment with Michael McIntyre 19:15 Ninja Warrior UK 16:25 The Middle 12:00 Hogan's Heroes featuring music from pop rockers The Vamps and Ben Shephard, Rochelle Humes and Chris Kamara 16:45 Shortlist 12:30 Hogan's Heroes stand-up comedy from Jason Manford. -

TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam

UK SALES Tel: 0345 2600 621 SatFi Email: [email protected] Web: www.satfi.co.uk satellite fidelity Freesat FTA (Free-to-Air) TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam 4Music BBC Radio Foyle Film 4 UK +1 ITV Westcountry West 4Seven BBC Radio London Food Network UK ITV Westcountry West +1 5 Star BBC Radio Nan Gàidheal Food Network UK +1 ITV Westcountry West HD 5 Star +1 BBC Radio Scotland France 24 English ITV Yorkshire East 5 USA BBC Radio Ulster FreeSports ITV Yorkshire East +1 5 USA +1 BBC Radio Wales Gems TV ITV Yorkshire West ARY World +1 BBC Red Button 1 High Street TV 2 ITV Yorkshire West HD Babestation BBC Two England Home Kerrang! Babestation Blue BBC Two HD Horror Channel UK Kiss TV (UK) Babestation Daytime Xtra BBC Two Northern Ireland Horror Channel UK +1 Magic TV (UK) BBC 1Xtra BBC Two Scotland ITV 2 More 4 UK BBC 6 Music BBC Two Wales ITV 2 +1 More 4 UK +1 BBC Alba BBC World Service UK ITV 3 My 5 BBC Asian Network Box Hits ITV 3 +1 PBS America BBC Four (19-04) Box Upfront ITV 4 Pop BBC Four (19-04) HD CBBC (07-21) ITV 4 +1 Pop +1 BBC News CBBC (07-21) HD ITV Anglia East Pop Max BBC News HD CBeebies UK (06-19) ITV Anglia East +1 Pop Max +1 BBC One Cambridge CBeebies UK (06-19) HD ITV Anglia East HD Psychic Today BBC One Channel Islands CBS Action UK ITV Anglia West Quest BBC One East East CBS Drama UK ITV Be Quest Red BBC One East Midlands CBS Reality UK ITV Be +1 Really Ireland BBC One East Yorkshire & Lincolnshire CBS Reality UK +1 ITV Border England Really UK BBC One HD Channel 4 London ITV Border England HD S4C BBC One London -

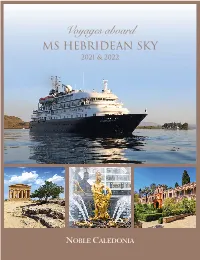

Voyages Aboard MS HEBRIDEAN SKY 2021 & 2022

Voyages aboard MS HEBRIDEAN SKY 2021 & 2022 2 Chester Close, Belgravia, London, SW1X 7BE +44 (0)20 7752 0000 | [email protected] www.noble-caledonia.co.uk Our current booking conditions apply to all reservations and are available on request. CONTENTS MS Hebridean Sky & Your Space On Board 04-05 Your Suite On Board 06-07 Your Dining On Board & Deck Plan 08-09 Your Onboard Team 10-11 The Voyages Island Life 12-13 White Nights in the Baltic 14-17 Sailing from the Baltic to Britain 18-19 Summer in the Isles 20-21 Islands on the Edge II 22-23 Summer in the Baltic 24-25 Iberian Stepping Stones 26-27 Passage to Morocco 28-29 Passage to Cape Verde 30-31 Antarctica – The Great White Continent 32-35 Scottish Island Odyssey 36-37 Spring in the Hebrides 38-39 Baltic Odyssey 40-41 Italy & Her Islands 42-43 Circumnavigation of Sicily 44-45 2 www.noble-caledonia.co.uk St Kilda A 0 YE RS 3 1 9 1 9 2 1 0 Dear Traveller 2 We are delighted to bring you this new brochure detailing the voyages which the all-suite, 118-passenger MS Hebridean Sky will undertake in 2021 and 2022. During the recent period of inactivity for our vessels owing to the global pandemic, we have been busy working on our future schedules and are very much looking forward to welcoming you on board once more. Over the following pages you will find details of some in-depth cruises around the Baltic, expedition cruises around the United Kingdom, voyages along the North African coast, cruises with a focus on Italy and her islands along with an expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula, South Georgia and the Falkland Islands.