Part I - Parasites, Human Hosts, and the Environment 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Resistencia Mapuche-Williche, 1930-1985

La resistencia mapuche-williche, 1930-1985. Zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin im März 2019. Vorgelegt von Alejandro Javier Cárcamo Mansilla aus Osorno, Chile 1 1. Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Stefan Rinke, Freie Universität Berlin ZI Lateinamerika Institut 2. Gutachter: apl. Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Böttcher, Freie Universität Berlin ZI Lateinamerika Institut Tag der Disputation: 09.07.2019 2 Índice Agradecimientos ....................................................................................................................... 5 Introducción .............................................................................................................................. 6 La resistencia mapuche-williche ............................................................................................ 8 La nueva historia desde lo mapuche ..................................................................................... 17 Una metodología de lectura a contrapelo ............................................................................. 22 I Capítulo: Características de la subalternidad y la resistencia mapuche-williche en el siglo XX. .................................................................................................................................. 27 Resumen ............................................................................................................................... 27 La violencia cultural como marco de la resistencia -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

Lautaro Aprendid Tdcticas Guerreras Cziado, Hecho Prisiouero, Fue Cnballerixo De Don Pedro De Valdivia

ISIDORA AGUIRRE (Epopeya del pueblo mapuche) EDITORIAL NASCIMENTO SANTIAGO 1982 CHILE A mi liermano Fernundo Aprendemos en 10s textos de historin que 10s a+.aucauos’ -ellos prelieren llamnrse “mapuches”, gente de la tierra- emu by’icosos y valzentes, que rnantuvieron en laque a 10s espagoks en una guerrn que durd tres siglos, qzie de nigh modo no fueron vencidos. Pero lo que machos tgnoran es qzic adrt siguen luckando. Por !a tierra en comunidad, por un modo de vida, por comervur su leizgua, sus cantos, sa cultura y sus tradiciones como algo VIVO y cotediano. Ellos lo resumen el?’ pocas palabras: ‘(Iuchamos por conservar nuez- tra identidad, por integrarnos a in sociedad chilena mnyorita- ria sin ser absorbidos por e1Ja”. Sabemos cdmo murid el to- pi Caupolica‘n, cdmo Lautaro aprendid tdcticas guerreras cziado, hecho prisiouero, fue cnballerixo de don Pedro de Valdivia. Sabemos, en suma, que no fueron vencidos, pero iporamos el “cdlno” y el “por que”‘. Nay nurneroros estudios antropoldgicos sobre 10s map- rhes pero se ha hecho de ellos muy poca difusidn. Y menos conocemos aun su vida de hoy, la de esu minoria de un me- dio rnilldiz de gentes que viven en sus “reducidus” redwcio- nes del Sur. Sabemos que hay machis, que kacen “nguillatu- 7 nes”, que hay festivales folcldricos, y en los mercados y en los museos podemos ver su artesania. Despuh de la mal llamada “Pacificacidn de la Arauca- nia” de fines del siglo pasado -por aquello de que la fami- lia crece y la tierra no-, son muchos los hz’jos que emigran a las ciudades; 10s nifios se ven hoscos y algo confundidos en las escuelas rurales, porque los otros se burlan de su mal castellano; sin embargo son nifios de mente cigil que a los seis afios hablan dos lenguas, que llevan una doble vida, por miedo a la discriminacidn, la de la ruca. -

Brochure Route-Of-Parks EN.Pdf

ROUTE OF PARKS OF CHILEAN PATAGONIA The Route of Parks of Chilean Patagonia is one of the last wild places on earth. The Route’s 17 National Parks span the entire south of Chile, from Puerto Montt all the way down to Cape Horn. Aside from offering travelers what is perhaps the world’s most scenic journey, the Route has also helped revitalize more than 60 local communities through conservation-centered tourism. This 1,740-mile Route spans a full third of Chile. Its ecological value is underscored by the number of endemic species and the rich biodiversity of its temperate rainforests, sub-Antarctic climates, wetlands, towering massifs, icefields, and its spectacular fjord system–the largest in the world. The Route’s pristine ecosystems, largely untouched by human intervention, capture three times more carbon per acre than the Amazon. They’re also home to endangered species like the Huemul (South Andean Deer) and Darwin’s Frog. The Route of Parks is born of a vision of conservation that seeks to balance the protection of the natural world with human economic development. This vision emphasizes the importance of conserving and restoring complete ecosystems, which are sources of pride, prosperity, and belonging for the people who live in and near them. It’s a unique opportunity to reverse the extinction crisis and climate chaos currently ravaging our planet–and to provide a hopeful, harmonious model of a different way forward. 1 ALERCE ANDINO National Park This park, declared a National Biosphere Reserve of Temperate Rainforests, features 97,000 acres of evergreen rainforest. -

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago De Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago de Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space vorgelegt von Walter Alejandro Imilan Ojeda Von der Fakultät VI - Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften Dr.-Ing. genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. -Ing. Johannes Cramer Berichter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter Herrle Berichter: Prof. Dr. phil. Jürgen Golte Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.12.2008 Berlin 2009 D 83 Acknowledgements This work is the result of a long process that I could not have gone through without the support of many people and institutions. Friends and colleagues in Santiago, Europe and Berlin encouraged me in the beginning and throughout the entire process. A complete account would be endless, but I must specifically thank the Programme Alßan, which provided me with financial means through a scholarship (Alßan Scholarship Nº E04D045096CL). I owe special gratitude to Prof. Dr. Peter Herrle at the Habitat-Unit of Technische Universität Berlin, who believed in my research project and supported me in the last five years. I am really thankful also to my second adviser, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Golte at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI) of the Freie Universität Berlin, who enthusiastically accepted to support me and to evaluate my work. I also owe thanks to the protagonists of this work, the people who shared their stories with me. I want especially to thank to Ana Millaleo, Paul Paillafil, Manuel Lincovil, Jano Weichafe, Jeannette Cuiquiño, Angelina Huainopan, María Nahuelhuel, Omar Carrera, Marcela Lincovil, Andrés Millaleo, Soledad Tinao, Eugenio Paillalef, Eusebio Huechuñir, Julio Llancavil, Juan Huenuvil, Rosario Huenuvil, Ambrosio Ranimán, Mauricio Ñanco, the members of Wechekeche ñi Trawün, Lelfünche and CONAPAN. -

Indigenous Peoples Rights And

ISBN 978-0-692-88605-2 Intercultural Conflict and Peace Building: The Experience of Chile José Aylwin With nine distinct Indigenous Peoples and a population of 1.8 million, which represents 11% of the total population of the country,1 conflicts between Indigenous Peoples and the Chilean state have increased substantially in recent years. Such conflicts have been triggered by different factors including the lack of constitutional recognition of Indigenous Peoples; political exclusion; and the imposition of an economic model which has resulted in the proliferation of large developments on Indigenous lands and territories without proper consultation, even less with free, prior, and informed consent, and with no participation of the communities directly affected by the benefits these developments generate. The growing awareness among Indigenous Peoples of the rights that have been internationally recognized to them, and the lack of government response to their claims—in particular land claims—also help to explain this growing conflict. Chile is one of the few, if not the only state in the region, which does not recognize Indigenous Peoples, nor does it recognize their collective rights, such as the right to political participation or autonomy or the right to lands and resources, in its political Constitution. The current Chilean Constitution dates back to 1980, when it was imposed by the Pinochet dictatorship. Indigenous Peoples have also been severely impacted by the market economy prevalent in the country. In recent decades, Chile has signed free trade and investment agreements with more than 60 other countries, in particular large economies from the Global North including the United States, Canada, the European Union, China and Japan, among others. -

Cnidaria, Hydrozoa: Latitudinal Distribution of Hydroids Along the Fjords Region of Southern Chile, with Notes on the World Distribution of Some Species

Check List 3(4): 308–320, 2007. ISSN: 1809-127X NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Cnidaria, Hydrozoa: latitudinal distribution of hydroids along the fjords region of southern Chile, with notes on the world distribution of some species. Horia R. Galea 1 Verena Häussermann 1, 2 Günter Försterra 1, 2 1 Huinay Scientific Field Station. Casilla 462. Puerto Montt, Chile. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Universidad Austral de Chile, Campus Isla Teja. Avenida Inés de Haverbeck 9, 11 y 13. Casilla 467. Valdivia, Chile. The coast of continental Chile extends over and Cape Horn. Viviani (1979) and Pickard almost 4,200 km and covers a large part of the (1971) subdivided the Magellanic Province into southeast Pacific. While the coastline between three regions: the Northern Patagonian Zone, from Arica (18°20' S) and Chiloé Island (ca. 41°30' S) Puerto Montt to the Peninsula Taitao (ca. 46°–47° is more or less straight, the region between Puerto S), the Central Patagonian Zone to the Straits of Montt (ca. 41°30' S) and Cape Horn (ca. 56° S) is Magellan (ca. 52°–53° S), and the Southern highly structured and presents a large number of Patagonian Zone south of the Straits of Magellan. islands, channels and fjords. This extension is A recent study, including a wide set of formed by two parallel mountain ranges, the high invertebrates from the intertidal to 100 m depth Andes on Chile’s eastern border, and the coastal (Lancellotti and Vasquez 1999), negates the mountains along its western edge which, in the widely assumed faunal break at 42° S, and area of Puerto Montt, drop into the ocean with proposes a Transitional Temperate Region between their summits, forming the western channels and 35° and 48° S, where a gradual but important islands, while the Andes mountain range change in the species composition occurs. -

Finding More Missing Pieces of a Puzzle in a Maze

FINDING MORE MISSING PIECES OF A PUZZLE IN A MAZE continuing the benthic exploration of channels and fjords in Southern Chilean Patagonia As an intricate system of fjords, labyrinth of channels and islands, each exemplifying different stages of glacial action and associated successional periglacial ecosystems, the Chilean fjord region offers extremely diversified benthic communities which, despite being unique worldwide, have been among the least studied so far. This region is threatened by different anthropogenic effects, such as global warming, the huge salmon farming industry planning to move into currently unprotected fjords, or illegal fishing of protected shellfish species such as ʻlocosʼ (Concholepas concholepas). In order to protect benthic fauna and monitor future changes in biodiversity distribution, it is essential to create accurate faunistic inventories. This is why we initiated a series of scientific expeditions, beginning in 2005. The first one lead us to the Guaitecas Archipelago, south of Grand Chiloé Island. The second took us to the fjords Tempano and Bernardo, including adjacent channels down to 49°S (see GME3, pp. 18–21). Enriched by our 2005 experience, we embarked in 2006 for another adventurous boat trip further south to 52°S. Our international team (seven in total) started Sample sorting through the night. gathering in Punta Arenas at the beginning of March, end of headed north through the channels along Puerto Eden as the austral summer. Some arrived directly from the Huinay well as around Isla Wellington to explore the exposed coast. Scientific Field Station, others from Germany and Belgium. We planned 2 dives/day, leaving about 9 hours of A 3 hour bus trip lead us to Puerto Natales, our departure navigation/day for the two week expedition. -

Ausencia Del Cuerpo Y Cosmología De La Muerte En El Mundo Mapuche

a tesis Ausencia del cuerpo y cosmología de la muerte Len el mundo mapuche: memorias en torno a la condición TESIS DE MEMORIA 2016 de detenido desaparecido de María José Lucero es una TESIS PARA OBTENER EL GRADO ACADÉMICO DE Otros títulos de la colección: contribución original y necesaria al conocimiento sobre LICENCIADA EN ANTROPOLOGÍA la represión al pueblo mapuche durante la dictadura. TESIS DE MEMORIA 2012 Afi rma la autora que la represión no fue solo política sino Ausencia del cuerpo y cosmología también racista. La aplicación del método etnográfi co, Nietos de ex presos políticos de TESIS DE de la muerte en el mundo mapuche: y específi camente la entrevista narrativa, permitió a la la dictadura militar: Transmisión MEMORIA memorias en torno a la condición de transgeneracional y apropiación de la autora conocer la concepción de la muerte y el signifi cado 2016 Historia de prisión política y tortura. de la condición de detenido desaparecido en seis familias detenido desaparecido XIMENA FAÚNDEZ ABARCA de la Araucanía. Se entrevistó a 7 mujeres familiares de detenidos desaparecidos. Se detalla la cosmovisión MARÍA JOSÉ LUCERO DÍAZ TESIS DE MEMORIA 2013 vinculada a la muerte, el impacto en sus vidas y la forma en Operaciones visuales de la Editora que las familias han ido recomponiendo la memoria de sus Nacional Gabriela Mistral: Fotografías seres queridos. para legitimar 1973-1976 DALILA MUÑOZ LIRA TESIS DE MEMORIA 2014 Del discurso al aula: recontextualización Ausencia del cuerpo y cosmología de la muerte en el mundo mapuche: memorias en torno a la condición de detenido desaparecido de textos escolares en materia de Dictadura militar y derechos humanos para sexto año básico en Chile SANNDY INFANTE REYES TESIS DE MEMORIA 2015 Exterminados como ratones Operación Colombo: creación dramatúrgica y teatro documental RODRIGO ANDRÉS MUÑOZ MEDINA TESIS DE MEMORIA 2016 Enunciar la ausencia. -

Alacalufe Oct.2018 Ok.Fh11

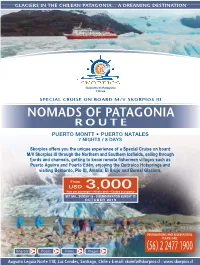

GLACIERS IN THE CHILEAN PATAGONIA... A DREAMING DESTINATION CHILE SPECIAL CRUISE ON BOARD M/V SKORPIOS III NOMADS OF PATAGONIA ROUTE PUERTO MONTT • PUERTO NATALES 7 NIGHTS / 8 DAYS Skorpios offers you the unique experience of a Special Cruise on board M/V Skorpios III through the Northern and Southern Icefields, sailing through fjords and channels, getting to know remote fishermen villages such as Puerto Aguirre and Puerto Edén, enjoying the Quitralco Hotsprings and visiting Bernardo, Pío XI, Amalia, El Brujo and Bernal Glaciers. From USD 3,000 Rate per passenger • Athens deck • Double occupancy SET SAIL: SUNDAY 06 - DISEMBARKATION SUNDAY 13 OCTOBER 2019 INFORMATIONS AND RESERVATIONS, PLEASE CALL Itinerary Places Rates Images Augusto Leguía Norte 118, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile • E-mail: [email protected] - www.skorpios.cl NOMADS OF PATAGONIA ROUTE, A SPECIAL CRUISE ON OCTOBER 2019, M/V SKORPIOS III NAVIGATION PROGRAM SATURDAY OCTOBER 5, 2019. Optional additional night in M/V Skorpios III previous to TRACK OF NAVIGATION the sailing. (Additional costs). Check-in from 18:00hrs onwards. Additional night includes accommodation in the booked cabin, dinner and breakfast-buffet (sail day). SUNDAY OCTOBER 6, 2019 12:00hrs. Set sail from Puerto Montt, through Tenglo Channel, Llanquihue Archipelago, sight of Calbuco village and crossing of Ancud Gulf. 17:00hrs. Navigation Chiloé Archipelago, Mechuque, Chauques, Caguache, Tranqui islands. Crossing of Corcovado Gulf. MONDAY OCTOBER 7, 2019 07:00hrs. Sailing through Moraleda Channel. 08:30hrs. Arrival to Puerto Aguirre Village in the Guaitecas Archipelago, visit to this picturesque fishermen village. 10:30hrs. Sailing through Ferronave, Pilcomayo, Paso Casma and Canal Costa channels, arriving at Quitralco Fjord at 15:00hrs. -

The Pangue/Ralco Hydroelectric Project in Chile's Alto Bíobío by Marc

Indigenous Peoples, Energy, and Environmental Justice: The Pangue/Ralco Hydroelectric Project in Chile’s Alto BíoBío By Marcos A. Orellana§ In the upcoming months, the reservoir of the Ralco dam, one of a series of dams along the Upper BíoBío River in Southern Chile, will destroy the pristine mountain ecosystem and will permanently and irreversibly disrupt the semi-nomadic lifestyle and cosmovision of the Mapuche/Pehuenche people.i At the same time, the communities affected by the dam will attempt to reconstruct their lives and culture using resources and rights provided by a “friendly settlement” reached by them with the Chilean Government and approved by the Inter-American Human Rights Commission (IACHR). This is the aftermath of a decade-long struggle by indigenous communities and environmental groups in defense of their rights against the project sponsor (Endesa -- a formerly public but now privatized company), the Chilean government, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Controversial issues raised in the BíoBío dams case present difficult public policy questions: How to reconcile respect for indigenous peoples’ cultures with energy demands by the dominant majority? How to operationalize prior informed consent with respect to large dams that involve resettlement and flooding of ceremonial and sacred sites? How to hold multinational corporations accountable for human rights violations? And how to determine the “public interest” in light of developmental needs and indigenous peoples’ cultures and rights? In general, this case highlights the fact that projects in violation of fundamental human rights do not constitute sustainable development. In other words, violation of the rights of indigenous peoples cannot be justified by the ‘public interest’ of the settler, dominant majority. -

Aspects of Social Justice Ally Work in Chilean Historical Fiction: the Case of the Pacification of Araucanía

Aspects of Social Justice Ally Work in Chilean Historical Fiction: The Case of the Pacification of Araucanía Katherine Karr-Cornejo Whitworth University Abstract Majority-culture writers often depict cultures different from their own, but approaching cultures to which an author does not belong can be challenging. How might we read dominant-culture portrayals of marginalized cultures that tell stories of injustice? In this paper I utilize the frame of identity development in social justice allies in order to understand the narratives dominant-culture authors use in fiction to reflect sympathetic views of indigenous justice claims. In order to do so, I study three historical novels set in Araucanía during the second half of the nineteenth century, considering historiographical orientation, representation of cultural difference, and understanding of sovereignty:Casas en el agua (1997) by Guido Eytel, Vientos de silencio (1999) by J.J. Faundes, and El lento silbido de los sables (2010) by Patricio Manns. I will show that fiction, even in validating indigenous justice claims, does not overcome past narratives of dominance. Representations can deceive us. The Mapuche warriors of Alonso de Ercilla’s epic poem La Araucana are safely in the past, and their cultural difference poses no threat to present-day nor- mative Chilean culture. However, that normative culture glorifies these fictional representations on the one hand and deprecates Mapuche communities today on the other. How did that hap- pen? Various Mapuche groups resisted Spanish colonization for centuries, restricting European expansion in today’s southern Chile. After Chilean independence from Spain in the early nine- teenth century, the conflict continued.