Statue ;Of Liberty National Monument "New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epilogue 1941—Present by BARBARA LA ROCCO

Epilogue 1941—Present By BARBARA LA ROCCO ABOUT A WEEK before A Maritime History of New York was re- leased the United States entered the Second World War. Between Pearl Harbor and VJ-Day, more than three million troops and over 63 million tons of supplies and materials shipped overseas through the Port. The Port of New York, really eleven ports in one, boasted a devel- oped shoreline of over 650 miles comprising the waterfronts of five boroughs of New York City and seven cities on the New Jersey side. The Port included 600 individual ship anchorages, some 1,800 docks, piers, and wharves of every conceivable size which gave access to over a thousand warehouses, and a complex system of car floats, lighters, rail and bridge networks. Over 575 tugboats worked the Port waters. Port operations employed some 25,000 longshoremen and an additional 400,000 other workers.* Ships of every conceivable type were needed for troop transport and supply carriers. On June 6, 1941, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 84 vessels of foreign registry in American ports under the Ship Requisition Act. To meet the demand for ships large numbers of mass-produced freight- ers and transports, called Liberty ships were constructed by a civilian workforce using pre-fabricated parts and the relatively new technique of welding. The Liberty ship, adapted by New York naval architects Gibbs & Cox from an old British tramp ship, was the largest civilian- 262 EPILOGUE 1941 - PRESENT 263 made war ship. The assembly-line production methods were later used to build 400 Victory ships (VC2)—the Liberty ship’s successor. -

What Is the Natural Areas Initiative?

NaturalNatural AAreasreas InitiativeInitiative What are Natural Areas? With over 8 million people and 1.8 million cars in monarch butterflies. They reside in New York City’s residence, New York City is the ultimate urban environ- 12,000 acres of natural areas that include estuaries, ment. But the city is alive with life of all kinds, including forests, ponds, and other habitats. hundreds of species of flora and fauna, and not just in Despite human-made alterations, natural areas are spaces window boxes and pet stores. The city’s five boroughs pro- that retain some degree of wild nature, native ecosystems vide habitat to over 350 species of birds and 170 species and ecosystem processes.1 While providing habitat for native of fish, not to mention countless other plants and animals, plants and animals, natural areas afford a glimpse into the including seabeach amaranth, persimmons, horseshoe city’s past, some providing us with a window to what the crabs, red-tailed hawks, painted turtles, and land looked like before the built environment existed. What is the Natural Areas Initiative? The Natural Areas Initiative (NAI) works towards the (NY4P), the NAI promotes cooperation among non- protection and effective management of New York City’s profit groups, communities, and government agencies natural areas. A joint program of New York City to protect natural areas and raise public awareness about Audubon (NYC Audubon) and New Yorkers for Parks the values of these open spaces. Why are Natural Areas important? In the five boroughs, natural areas serve as important Additionally, according to the City Department of ecosystems, supporting a rich variety of plants and Health, NYC children are almost three times as likely to wildlife. -

Fall Winter 2018 /2014 Volume / Volume Xxxix Xxxv No

THE NEWSLETTER OF NEW YORK CITY AUDUBON FALL WINTER 2018 /2014 VOLUME / VOLUME XXXIX XXXV NO. NO.3 4 THE URBAN AUDUBON The NYC Green Roof Researchers Alliance Trip Leader Profile: Nadir Souirgi The Merlin (Falco columbarius) Uptown Birds Fall 2018 1 NYC AUDUBON MISSION & STATEMENT Mission: NYC Audubon is a grassroots community that works for the protection of PRESIDENT’S PERCH Jeffrey Kimball wild birds and habitat in the five boroughs, improving the quality of life for all New Yorkers. ew York City Audubon is the most urban Audubon chapter in North America. Our Vision: NYC Audubon envisions a day when office is on the 15th floor of a beautiful Art Deco building in Chelsea, not in a former birds and people in the five boroughs enjoy a healthy, livable habitat. Nfarmhouse on 40-something acres. Being in a large, highly developed city has its chal- lenges, of course, but it also presents opportunities, and even magical moments. I am inspired THE URBAN AUDUBON Editors Lauren Klingsberg & Marcia T. Fowle daily by the abundance of wildlife present in our urban midst. That each year the City plays host Managing Editor Andrew Maas to nearly a third of all the bird species found in North America is truly astonishing. Raccoons, Newsletter Committee Seth Ausubel; Ellen Azorin; Lucienne Bloch; Ned Boyajian; chipmunks, and woodchucks flourish in our City parks, while seals, dolphins, and even the occa- Suzanne Charlé; Diane Darrow; sional whale grace our harbor. Endangered turtles nest right under flight paths at JFK airport. Meryl Greenblatt; Catherine Schragis Heller; NYC Audubon started in 1979, when a small and dedicated group of naturalists and Mary Jane Kaplan; Abby McBride; Hillarie O’Toole; Don Riepe; birdwatchers (there were no “birders” back then, just “birdwatchers”) organized a chapter here Carol Peace Robins in the City. -

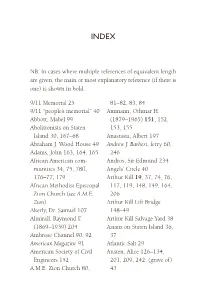

In Cases Where Multiple References of Equivalent Length Are Given, the Main Or Most Explanatory Reference (If There Is One) Is Shown in Bold

index NB: In cases where multiple references of equivalent length are given, the main or most explanatory reference (if there is one) is shown in bold. 9/11 Memorial 25 81–82, 83, 84 9/11 “people’s memorial” 40 Ammann, Othmar H. Abbott, Mabel 99 (1879–1965) 151, 152, Abolitionists on Staten 153, 155 Island 30, 167–68 Anastasia, Albert 197 Abraham J. Wood House 49 Andrew J. Barberi, ferry 60, Adams, John 163, 164, 165 246 African American com- Andros, Sir Edmund 234 munities 34, 75, 78ff, Angels’ Circle 40 176–77, 179 Arthur Kill 19, 37, 74, 76, African Methodist Episcopal 117, 119, 148, 149, 164, Zion Church (see A.M.E. 206 Zion) Arthur Kill Lift Bridge Akerly, Dr. Samuel 107 148–49 Almirall, Raymond F. Arthur Kill Salvage Yard 38 (1869–1939) 204 Asians on Staten Island 36, Ambrose Channel 90, 92 37 American Magazine 91 Atlantic Salt 29 American Society of Civil Austen, Alice 126–134, Engineers 152 201, 209, 242; (grave of) A.M.E. Zion Church 80, 43 248 index Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing- Boy Scouts 112 Room Companion 76 Breweries 34, 41, 243 Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Bridges: 149, 153 Arthur Kill Lift 148–49 Barnes, William 66 Bayonne 151–52, 242 Battery Duane 170 Goethals 150, 241 Battery Weed 169, 170, Outerbridge Crossing 150, 171–72, 173, 245 241 Bayles, Richard M. 168 Verrazano-Narrows 112, Bayley-Seton Hospital 34 152–55, 215, 244 Bayley, Dr. Richard 35, 48, Brinley, C. Coapes 133 140 British (early settlers) 159, Bayonne Bridge 151–52, 176; (in Revolutionary 242 War) 48, 111, 162ff, 235 Beil, Carlton B. -

The Island of Tears: How Quarantine and Medical Inspection at Ellis Island Sought to Define the Eastern European Jewish Immigrant, 1878-1920

The Island of Tears: How Quarantine and Medical Inspection at Ellis Island Sought to Define the Eastern European Jewish Immigrant, 1878-1920 Emma Grueskin Barnard College Department of History April 19th, 2017 Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows worldwide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door! - Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus” (1883) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Acknowledgements 1 II. Introduction 2 Realities of Immigrant New York Historiography III. Ethical Exile: A Brief History of Quarantine and Prejudice 9 The Ethics of Quarantine Foucault and the Politics of The Ailing Body Origins of Quarantine and Anti-Jewish Sentiments IV. Land, Ho! Quarantine Policy Arrives at Ellis Island 22 Welcoming the Immigrants Initial Inspection and Life in Steerage Class Divisions On Board Cholera of 1892 and Tammany Hall Quarantine Policy V. Second Inspection: To The Golden Land or To the Quarantine Hospital 38 The Dreaded Medical Inspection Quarantine Islands, The Last Stop VI. Conclusion 56 VII. Bibliography 58 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has certainly been a labor of love, and many people were involved in its creation. -

2001 Staten Island Cycling

Staten Island Ferry Connections Bridge Connections Newark Airport Port Elizabeth Broadway St George Ferry Terminal Bayonne Bridge - Staten Island Av E Ferry Slips North State Hwy 169 N NEW JERSEY Morningstar Rd Elizabeth Westfield Caution: y Cyclists must use lower level of ferry Bayonne Bidge dwa and terminal. Parking Ferry roa N Offices Queuing B Av E 22nd ew H ook A Caution: Up Rahway SIRTOA Harbor Shuttle Cyclists must Up Platforrms Bayonne cce use lower level ss of ferry and Walker NEW JERSEY terminal. St. George Terminal Staten Island Ferry Trantor Pl (to Pier 11,Downtown Manhattan) Parking Lot Parking Down Down Saint Georges Newark Bay NY Fast Ferry J F Kennedy Blvd Richmond County Savings Bayway Ramp Bayonne Bridge - New Jersey Bank Stadium North Ramp Bayonne Bridge - New Jersey Richmond St. George Richmond Terrace 2nd Ferry (to Midtown Manhattan, E.34th St) Kennedy Blvd Carroll St Marks Terminal Bank WesterveltRANDALL (To Whitehall Ferry Terminal, Downtown Manhattan) Jersey Caution - Stairs!! MANOR S.I. Snug Ham Cyclists must iltonMuseum N dismount VanBuren Snug Lafayette Fillmore Borough Delafield Harbor Eadie Highview Belmont H Egmont Hall E Buchanan Curtis all Kill van Kull elia Cultural Ctr arvard W uyler Am Clinton Botanical Tysen Sch Livingston Melville NEW Crescent C ales StMa W Garden Montgomery Hyatt Harbor Shuttle Monroe BRIGHTON ton Sherman DanielLow House Lay en RichmondTerrace Howard Linden Children’s aft B T Tompkins Nassau tra Owl’s Head Bayonne Bridge Van rks Bayridge Henderson ism Hendricks eral Harrison Museum -

New York City Audubon Harbor Herons Project

NEW YORK CITY AUDUBON HARBOR HERONS PROJECT 2007 Nesting Survey 1 2 NEW YORK CITY AUDUBON HARBOR HERONS PROJECT 2007 NESTING SURVEY November 21, 2007 Prepared for: New York City Audubon Glenn Phillips, Executive Director 71 W. 23rd Street, Room 1529 New York, NY 10010 212-691-7483 www.nycaudubon.org Prepared by: Andrew J. Bernick, Ph. D. 2856 Fairhaven Avenue Alexandria, VA 22303-2209 Tel. 703-960-4616 [email protected] With additional data provided by: Dr. Susan Elbin and Elizabeth Craig, Wildlife Trust Dr. George Frame, National Park Service David S. Künstler, New York City Department of Parks & Recreation Don Riepe, American Littoral Society/Jamaica Bay Guardian Funded by: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Hudson River Estuary Habitat Grant and ConocoPhillips-Bayway Refinery 3 ABSTRACT . 5 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 7 METHODS . 8 TRANSPORTATION AND PERMITS . 9 RESULTS . 10 ISLAND ACCOUNTS . 12 Long Island Sound–Pelham/New Rochelle. 12 Huckleberry Island. 12 East River, Hutchinson River, and 2007 Long Island Sound ............................ .13 Nesting Survey Goose Island. .13 East River ......................................14 North Brother Island. 14 South Brother Island. .15 Mill Rock. 16 U Thant. .17 Staten Island – Arthur Kill and Kill Van Kull . .17 Prall’s Island. 17 Shooter’s Island . 19 Isle of Meadows . 19 Hoffman Island . 20 Swinburne Island . .21 Jamaica Bay ................................... .22 Carnarsie Pol . 22 Ruffle Bar. 23 White Island . .23 Subway Island . .24 Little Egg Marsh . .24 Elders Point Marsh–West. .25 Elders Point Marsh – East . 25 MAINLAND ACCOUNTS . 26 SPECIES ACCOUNTS . 27 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS . 29 Acknowledgements . .33 Literature Cited . 34 TABLES . 35 APPENDIX . -

New York City, the Lower Hudson River, and Jamaica Bay

3.4 New York City, the Lower Hudson River, and Jamaica Bay Author: Elizabeth M. Strange, Stratus Consulting Inc. Species and habitats in the region encompassing such as beach nourishment, dune construction, New York City, the lower Hudson River, the and vegetation wherever possible. Planners East River, and Jamaica Bay are potentially at expect that the only sizeable areas in the New risk because of sea level rise. Although the York City metropolitan area that are unlikely to region is one of the most heavily urbanized areas be protected are portions of the three Special along the U.S. Atlantic Coast, there are Natural Waterfront Areas (SNWAs) designated nonetheless regionally significant habitats for by the city: Northwest Staten Island/Harbor fish, shellfish, and birds in the area, and a great Heron SNWA; East River–Long Island Sound deal is known about the ecology and habitat SNWA; and Jamaica Bay SNWA. needs of these species. TIDAL WETLANDS Based on existing literature and the knowledge of local scientists, this brief literature review Staten Island. Hoffman Island and Swinburne discusses those species that could be at risk Island are National Park Service properties lying because of further habitat loss resulting from sea off the southeast shore of Staten Island; the level rise and shoreline protection (see Map 3.2). former has important nest habitat for herons, and 252 Although it is possible to make qualitative the latter is heavily nested by cormorants. The statements about the ecological implications if Northwest Staten Island/Harbor Herons SNWA sea level rise causes a total loss of habitat, our is an important nesting and foraging area for 253 ability to say what the impact might be if only a herons, ibises, egrets, gulls, and waterfowl. -

General History of the Jamaica Bay, Breezy Point

GENERAL HISTORY OF THE JAMAICA BAY, BREEZY POINT, AND STATEN ISLAND UNITS, GATEWAY NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, NEW YORK NY Tony P. Wrenn 31 October 1975 ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION, FORMATTING AND EDITING 2002 DATE: 31 October 1975 TO: E. Blaine Cliver National Park Service North Atlantic Regional Office 150 Causeway Street Boston, MA 02114 FROM: Tony P. Wrenn Historic Preservation Consultant P. O. Box 1112 Alexandria, VA 22313 SUBJECT: General History, Gateway National Recreation Area, New York, NY Jamaica Bay, Breezy Point, and Staten Island Units (Order Number: PX 1600-5-0353) DESCRIPTION: Furnish a study and report on historical buildings within the Gateway National Recreation Area, excluding those located within the Sandy Hook Unit. The report should emphasis those buildings which the study indicates are of importance, explaining why these conclusions have been reached. A general over-all history and its association with the buildings should also be included as well as sources of future research and the types of material to be found in these sources. Hereby submitted in completion of the study is the report, which includes a listing of sources used. Attachments include photographs, drawings, surveys, maps, and copies from both secondary and primary sources. /s/Tony P. Wrenn ___________________________________ Tony P. Wrenn Historic Preservation Consultant 2 SUMMARY Areas within the Jamaica Bay, Breezy Point, and Staten Island Units are presented in that unit order, with each area covered separately. For each area there is first a location, then a general history, notes on existing structures (if any), comments, and suggestions for additional research. a sizable amount of manuscript material, graphics, and limited-circulation printed material uncovered during the research effort is transmitted with the report; these materials are described briefly by their listing in Appendix B of the report. -

Brooklyn Staten Island Queens

Metro North Ludlow Tibbets Brook Park Yonkers N Columbus Yonkers Raceway W Lincoln Riverdale Broadway Metro North Wilson Mt.Vernon West Mt Vernon Woods Lower Manhattan & Downtown Brooklyn -- Subway and Streets Mt. St. Vincent Metro North College Mt. Vernon East Park 9th W 261 St W 263 St Kimball Feeney Metro North Park W14 4 Pelham 8th Av F N R W13 1 5 2 V Q W South County Trailway 7th Av 6 GreenwichL Abbot 3 Delafield Palisade Liebig Gansevoort D Tyndall Fieldstone Gramercy LIRR Spencer Huxley Huguenot W4 Independence McLean Horatio 6thB Av Park Long Island W 259 St E 23 E 243 St N Jane City Ash NORTH Metro W 3rd Netherland E 242 St 4th Metro North Beechwood RIVERDALE S 5th W12 5th Av Park North Wakefield Penfield E 21 Box Riverdale W 256 St Faraday E 241 St MOUNT Cemetery Bethune A Union Riverdale E 240 St St Ouen GREENWICH PATH W 256 St y VERNON Memorial Irving Clay Murdock Square W 254 St w Hudson Bank C Cranford Field VILLAGE Dupont k Commercial 2 Seton P Monticello Mosholu Av Fieldstone Hill Perry Valles E W 10 Sylvan Post Bullard E 14th Riverdale W 254 St n E 241 St Bronx E 241 St River Eagle o WOODLAWN Carpenter Charles Park Matilda W 10 W 9 E 20 Sycamore s E 240 St E 239 St 4th Av 4th Richardson Hutchinson Hudson River Greenway d Freeman H u E 239 St Nereid 1st Av Blackstone e H Vireo Field Christopher W University nry E 238 St Wilder Manhattan Independence DeReimer Martha Nereid Bedford 8 Oneida Katonah Edson Franklin E 237 St 5 East Grace Kepler W Sanford Waverly West Bleecker Post y Bruner Wave Hill Napier E 236 St Environm. -

Foundation for Planning

GatewayGateway National National Recreation Recreation Area Area - Final- Final General General Management Management Plan Plan / Environmental/ Environmental Impact Impact Statement Statement - Chapter One Purpose of and Need for the Plan 3 Imagining a New Gateway 3 A Special Place at the Urban Edge 3 The Planning Area 5 Foundation for the Future 9 Park Purpose 9 Coastal Defense Fortifications and Military Areas 11 Coastal Systems and Natural Areas 11 Maritime Resources 12 Diverse Recreation Opportunities 13 Other Important Resources and Values 14 Planning Challenges 14 Responding to Climate Change and Sea-level Rise 15 Preserving Gateway’s Heritage 16 Addressing Marine Resources and Water Quality 17 Engaging New Audiences 18 Accessing the Park 19 Providing Appropriate Facilities 19 Plan Development 20 New Partners, New Vision 20 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments 22 Servicewide Laws and Policies 23 Impact Topics 24 Impact Topics Retained for Further Analysis 25 Impact Topics Dismissed from Analysis 28 Related Plans 29 National Park Service Plans 29 Other Agency Plans 31 Next Steps and Plan Implementation 32 Chapter 1: Foundation for Planning 1 Gateway National Recreation Area - Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement - Chapter One A park, however splendid, has little appeal to a family that cannot reach it … The new conservation is built on a new promise— to bring parks closer to the people. —President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1968 2 Gateway National Recreation Area - Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement - Chapter One Purpose of and Need for the Plan Imagining a New Gateway It was a bold idea: bring national parks closer to people in cities. -

Gateway National Recreation Area Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Gateway National Recreation Area New Jersey and New York Contact Information For more information about the Gateway National Recreation Area Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (718) 354-4606 or write to: Superintendent, Gateway National Recreation Area, 210 New York Avenue, Staten Island, NY 10305 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Gateway National Recreation Area resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • Forts Hancock, Tilden, and Wadsworth comprise one of the largest sets of military installations and distinctive fortifications in the country, dating from pre-Civil War through the 20th century. These installations represent a long period of military presence and served as the defense of New York City, the largest city in the United States. GATEWAY NATIONAL RECREATION AREA provides a national park experience • Gateway contains an assemblage of coastal ecosystems in the country’s largest metropolitan formed by natural features, both physical and biological, that area. The park preserves a mosaic of include barrier peninsulas, estuaries, oceans, and maritime coastal ecosystems and natural areas uplands. The habitats that comprise these ecosystems, so interwoven with historic coastal rare in such highly developed areas, support a rich biota defense and maritime sites around that includes migratory birds; marine finfish and shellfish; New York’s Outer Harbor.