Making Shoji Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Garden Path

Photo: David M. Cobb THE GARDEN PATH MARCH 2016 • VOLUME 15 • NUMBER 3 WELCOME BACK MEMBERS SOME TIPS FOR VISITING: On March 1, just as Portland is turning to the soft breezes and opening v Construction will continue outside the Garden gates buds of spring, the Portland Japanese Garden will welcome visitors to until Spring 2017 return to our five familiar landscapes. From new leaf growth on our v The shuttle from our parking lot to the Admission Gate will Japanese maples, to pink petals appearing on our 75-year-old weeping be available Friday, Saturday, and Sundays only cherry tree, Members will have plenty of springtime sights to enjoy. v Consider taking public transportation; much of the lower Gardeners have spent the last six months getting the Garden into parking lot is being used for construction staging peak condition, and plants are well-rested and healthy—rejuvenated v Trimet Bus-Line 63 runs every hour, Monday through Friday for spring. Inside the Garden and out, this year promises to be one of v The Garden will switch to summer hours on March 13 beauty, culture, and growth. A JOURNEY FAMILIAR AND NEW Mr. Neil was born and raised on the western slope of the Rocky Members walking up the hillside path will notice a new set of stairs with Mountains in Colorado. The fantastic array of wind-swept trees in the an altered entrance into the Garden. The stair landing allows visitors landscape instilled in him a deep fascination with their beauty and the best view to observe ongoing construction, especially the progress the resilient nature of plants. -

The Lesson of the Japanese House

Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XV 275 LEARNING FROM THE PAST: THE LESSON OF THE JAPANESE HOUSE EMILIA GARDA, MARIKA MANGOSIO & LUIGI PASTORE Politecnico di Torino, Italy ABSTRACT Thanks to the great spiritual value linked to it, the Japanese house is one of the oldest and most fascinating architectural constructs of the eastern world. The religion and the environment of this region have had a central role in the evolution of the domestic spaces and in the choice of materials used. The eastern architects have kept some canons of construction that modern designers still use. These models have been source of inspiration of the greatest minds of the architectural landscape of the 20th century. The following analysis tries to understand how such cultural bases have defined construction choices, carefully describing all the spaces that characterize the domestic environment. The Japanese culture concerning daily life at home is very different from ours in the west; there is a different collocation of the spiritual value assigned to some rooms in the hierarchy of project prioritization: within the eastern mindset one should guarantee the harmony of spaces that are able to satisfy the spiritual needs of everyone that lives in that house. The Japanese house is a new world: every space is evolving thanks to its versatility. Lights and shadows coexist as they mingle with nature, another factor in understanding the ideology of Japanese architects. In the following research, besides a detailed description of the central elements, incorporates where necessary a comparison with the western world of thought. All the influences will be analysed, with a particular view to the architectural features that have influenced the Modern Movement. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

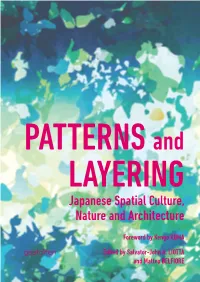

Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture

PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword by Kengo KUMA Edited by Salvator-John A. LIOTTA and Matteo BELFIORE PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword: Kengo KUMA Editors: Salvator-John A. LIOTTA Matteo BELFIORE Graphic edition by: Ilze PakloNE Rafael A. Balboa Foreword 4 Kengo Kuma Background 6 Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore Patterns, Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature, and Generative Design 8 Salvator-John A. Liotta Spatial Layering in Japan 52 Matteo Belfiore Thinking Japanese Pattern Eccentricities 98 Rafael Balboa and Ilze Paklone Evolution of Geometrical Pattern 106 Ling Zhang Development of Japanese Traditional Pattern Under the Influence of Chinese Culture 112 Yao Chen Patterns in Japanese Vernacular Architecture: Envelope Layers and Ecosystem Integration 118 Catarina Vitorino Distant Distances 126 Bojan Milan Končarević European and Japanese Space: A Different Perception Through Artists’ Eyes 134 Federico Scaroni Pervious and Phenomenal Opacity: Boundary Techniques and Intermediating Patterns as Design Strategies 140 Robert Baum Integrated Interspaces: An Urban Interpretation of the Concept of Oku 146 Cristiano Lippa Craft Mediated Designs: Explorations in Modernity and Bamboo 152 Kaon Ko Doing Patterns as Initiators of Design, Layering as Codifier of Space 160 Ko Nakamura and Mikako Koike On Pattern and Digital Fabrication 168 Yusuke Obuchi Foreword Kengo Kuma When I learned that Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore in my laboratory had launched a study on patterns and layering, I had a premonition of something new and unseen in preexisting research on Japan. Conventional research on Japan has been initiated out of deep affection for Japanese architecture and thus prone to wetness and sentimentality, distanced from the universal and lacking in potential breadth of architectural theories. -

How Traditional Japanese Architecture Can Contribute to Contemporary Sustainable Design Practices Courtney Angen Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Environmental Studies Honors Papers Environmental Studies 1-1-2013 Concept and Technique: How Traditional Japanese Architecture can contribute to Contemporary Sustainable Design Practices Courtney Angen Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/envirohp Recommended Citation Angen, Courtney, "Concept and Technique: How Traditional Japanese Architecture can contribute to Contemporary Sustainable Design Practices" (2013). Environmental Studies Honors Papers. Paper 10. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/envirohp/10 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Concept(and(Technique:( How(Traditional(Japanese(Architecture(can(contribute(to(Contemporary( Sustainable(Design(Practices( ( Courtney!Angen! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Connecticut!College! Department!of!Environmental!Studies! ! In!Collaboration!with:! Department!of!Architectural!Studies! Department!of!East!Asian!Studies! ! Fall!2012B!Spring!2013! Table&of&Contents& & ! Introduction& ! 1! & ! ! & Chapter&1:! ! ! !Defining!Sustainability!! ! Introduction! ! 6! -

THEMES, SCENES, and TASTE in the HISTORY of JAPANESE GARDEN ART Promotoren: Ir.M .J

THEMES, SCENES, AND TASTE IN THE HISTORY OF JAPANESE GARDEN ART Promotoren: Ir.M .J . Vroom Hoogleraar in de Landschapsarchitektuur Dr.W.R.vanGulik Bijzonder Hoogleraar in de Materiële Cultuurkunde en Kunstgeschiedenis van Japan en Korea (Rijks universiteit Leiden) Dr.M .Nakamur a Hoogleraar in de Landschapsarchitektuur (Kyoto University) VïJÖ2lO\y\Z0$ STELLINGEN 1. De situering van tuin en gebouwen van de paleizen uit de Japanse Heian tijd was het resultaat van bescheiden aanpassingen van de bestaande topografie. (Dit proefschrift) 2. Planten werden in de Heian paleistuin geplant om een stemming weer te geven, niet omwille van een estetisch beeld. Deze stemming berustte op het oproepen en herkennen van welbekende poëtische thema's, onlosmakelijk verbonden met bepaalde plantensoorten. (Dit proefschrift) 3. Vroeg veertiende eeuwse tuinen in Japan, die vormgegeven zijn met gebruikmaking van Chinese kompositietheoriën uit de Song landschapsschilderkunst, zijn ontworpen door Chinezen. (Dit proefschrift) k. De opkomst van een groep van professionele, maar ongeletterde tuinenmakers in de tweede helft van de middeleeuwen in Japan, droeg bij aan het totstandkomen van een vormgeving die het scheppen van taferelen ten doel had, welke gewaardeerd werden op uiterlijke schoonheid. (Dit proefschrift) 5. De Japanse 'droge landschapsstijl' (karesansui) is als zodanig in de twintigste eeuw gedefinieerd. (Dit proefschrift) 6. Het valt op zijn minst te betwijfelen dat middeleeuwse tuinenmakers in Japan de bedoeling hadden de Zen filosofie tot uitdrukking te brengen. De gedachte dat de Zen filosofie met materiële vormen in een tuin tot uitdrukking gebracht wordt dateert uit de dertiger jaren van deze eeuw. (Dit proefschrift) 7. De inrichting van de Japanse zestiende eeuwse theetuin was in de grond van de zaak funktioneel. -

Shinden Zukuri) Takes Its Name from the Shinden, the Central Structure in Such Complexes

THE SHINDEN STYLE Residences of the Heian Aristocracy The Shinden style (shinden zukuri) takes its name from the shinden, the central structure in such complexes. The word literally means "hall for sleeping." Thou gh every known Shinden-style complex had its own unique aspects, most faced sout h over a courtyard where ceremonies and entertainments were performed. South of the courtyard a pond was dug with a central island reached by bridges. At the po nd's periphery might be a hill, made from earth excavated to create the pond, wi th trees planted on it. Boating on the pond was a favorite form of relaxation fo r the fortunate residents of such mansions. Shinden buildings and Grounds The shinden hall was the residence of the master of the house and place where h e met guests and officiated at rites and festivities. Projecting from one or mor e sides of the shinden hall were hallways (watadono) leading to subsidiary space s called tainoya (literally meaning "opposed halls"), mostly allotted to family members and their servants. Corridors (rô) led from these tainoya to the pond, whe re they ended in small "finishing pavilions" (tsuridono) or "foutain pavilions" (izumidono). Midway along these southern corridors were "inner gates" (chumon) t hrough which one entered the complex, and the corridors were accordingly called "inner gate corridors" (chumonrô). These corridors were quite spacious and contain ed the offices of the household staff. Shinden residences were usually built on one-block lots (120 square meters), th ough some, like the Higashi Sanjo mansion of the Fujiwara, was two blocks north to south. -

The Journal Wantage

KOTOKEN KAJIHARA ; MASTER POLISHER A PERFECT SASHIKOMI OR HAOIROI POLISH, A NEW HABAKI, A SHIRASAVA, A TSlJNAQI. FOR THE kOSHIRAE , APPRAISED AND SAFELY RETURNED ALL IN 4 MONTHS DETAILS AND PRICE'S FROM U K AGENT Or 0 CURTIS THE MILL LOCKS LANE THE JOURNAL WANTAGE OXFORDSHIRE TO-KEN goeiETY OF OREAT BRITAIN JANUARY 1983 Wcssex Press, Wantage. ~~~~Sothebys~~~~ London Fine Japanese Works of Art JAPANESE ARMS & ARMOUR including Japanese Swords, Swordfittings and Armour rlll'.·'IJ -·-~ }r• ~.,, f '\ f I, '"•"' .\ Japanese swords, sword fittings and armour are included in our periodic Arms and Armour sales. A shakudo nanako Tsuba, signed Tokakushi lshiguro Masatsune, 7.6 cm., sold in London on 17th March 1982 for £5,720, Enquiries: Chris~opher Alien Ex~ 320. a world public auction record prict. Funher sales including Japanese Swords, Swordfittings and Armour will be held on 16th Items are now being accep~ed for our nex~ sale. March and 8th June 1983 Enquiries to: David]. H. Macfarlane or Catriona Home Catalogue subscriptio11s £9 per mmwll illcludi11g postage. Sotheby Parke Bernet & Co., 34-35 New Bond Street, London WIA 2AA Blens~ock House, 7 Blenheim Srreet, New Bond Scree~, Telephone: (0 I) 493 8080 Telex: 24454 SPBLON G London WIY OAS. Tel: 01-629 6602 Telegrams: Abinitio, London W I Shinto Kantei Pr ogramme 114 This lval.cizashi is by; -~.\. : Hi ! d•I SHODA I TA DAYOSHI l -, . :.J t The carving (kirimono is by ; f r.tUNENAG:\ \t'inners U. K.: J. Eurro~s B. IIo\vells Holland : Han Bing Siong U . S ~ A . : C. Dird G. -

The Institute of Emptiness and Ephemerality the Poetics Of

The institute of emptiness and ephemerality The poetics of Japanese sensibility Research paper | Explore Lab Claartje L’Herminez Technical University Delft Introduction o The illusion of progress and spiritual emptiness o Spirituality | Nature and Architecture o Japanese philosophy and architecture • Main research question • Sub-questions • Follow-up question Methods and Parameters Findings and Discussion| The essence of Japanese architectural space The relation between man (architecture) and nature • The Machiya | A traditional Japanese townhouse + En | The transitional space o Horizontal orientation o The roof o The column o The corridor and the patio o The veranda + Thresholds o The step o A Layered façade o The gate + Permeability + Referencing nature’s qualities o Transferring elements Simplicity | Poetics of the ordinary Ephemerality, Emptiness and Ambivalence Ephemerality | The impermanence of everything + Vitality | Adaptability to natural forces and the weather + Impermanence | Natural materials + Flexible space | Temporary space + Imperfection | Incompleteness Emptiness | The origin/ end of everything + The concept of space + The notion of Ma o Ma | The domain of objectivity o Ma | The domain of subjectivity o Ma | the domain of metaphysics Relativity | The ambivalent nature of everything + Ambivalence contributing to an atmosphere of sacredness o (Im)materiality o The Glimpse | perceiving part of a whole o Darkness o Limit/ boundlessness o Timelessness o Perspective illusions Sequential experience | a sensory experience of -

The Historical Development of Japanese Capital Cities, Their Houses, Temples, and Gardens

The Historical Development of Japanese Capital Cities, their Houses, Temples, and Gardens Henrik Falck Linköping University 2004-06-06 Summary Japanese buildings are traditionally built according to the post and lintel principle. They are most often made of wood. Exterior and interior partitioning is flexible and is achieved by screens or shutters. Corridors connect the buildings of a complex. Japanese gardens emerged from the rearrangement of natural clusters of stone in roped-off sacred Shinto shrine areas. The Japanese garden has six basic compositional elements, which are described in the ancient book, the Sakuteiki. Basic prototypes are implemented by intensifying and recreating nature. The capitals of Heijō-kyō and Heian-kyō were established in the 8th century based on a Chinese model. They were arranged in a grid of city blocks. Merchants lived in townhouses in the city and commerce was carried out on the markets. The Shinden Style is the building style preferred by the Heian aristocracy. Its grounds usually occupy two city blocks north-south and features a pond as well as numerous other features, and a complex of buildings and corridors. The interior is fairly open and flexible through the use of screens. Temples began to be built as Buddhism had been introduced from the mainland. Japanese Buddhist temples have features such as a pagoda, which varies in form. Tōdaiji and Byōdōin are prime examples of the temples of this time. During Medieval times a new style of building called the Great Buddha Style was introduced from China. This style is simple yet dignified and suited for building massive structures in short time. -

FORM, FUNCTION, and MULTISENSORY AESTHETICS in HEIAN WOMEN's INTERIOR SPACE by ZOE LALONDE a THESIS Pres

ELEGANTLY INTRIGUING: FORM, FUNCTION, AND MULTISENSORY AESTHETICS IN HEIAN WOMEN’S INTERIOR SPACE by ZOE LALONDE A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Zoe LaLonde Title: Elegantly Intriguing: Form, Function, and Multisensory Aesthetics in Heian Women’s Interior Space This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Akiko Walley Chairperson Glynne Walley Member Maile Hutterer Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019 ii © 2019 Zoe LaLonde This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Zoe LaLonde Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2019 Title: Elegantly Intriguing: Form, Function, and Multisensory Aesthetics in Heian Women’s Interior Space This thesis investigates the roles of partitions (shutters, blinds, screens, and curtains) within eleventh-century Japanese palace architecture known as shinden-zukuri. Using classical literature, I analyze how noblewomen used partitions to position themselves as active subjects in their social engagements by controlling the attention and perception of visitors. Chapter 1 evaluates the multisensorial stimuli created by a partitioned courtly interior space. Chapter 2 focuses on partitions as mediating devices around women on two topics: spatial articulations of their purity, health, and bodily integrity; and the act of concealment and revelation as a mechanism to emphasize their presence, comparable to the environment surrounding a “hidden” Buddha (hibutsu). -

Appended Table1 (Re: Article 7) Classification of Articles 1. Manufactured Foods and Nonessential Goods Manufactured Foods Sausa

Appended Table1 (Re: Article 7) Classification of Articles 1. Manufactured Foods Manufactured Sausage and Nonessential Goods Foods Ice cream Kamaboko *Kamaboko: steamed fish paste Kamaboko board *Kamaboko: steamed fish paste Nori *Nori: seaweed Sugar cube Udon *Udon: noodle Pastry Biscuit Cracker Senbei *Senbei: flat rice cracker Arare *Arare: small cubic rice cracker Bun with red bean paste filling Wafer with red bean paste filling Pie Cake Doughnut Caramel candy Candy Chocolate Confectionery stick Solid curry Sushi Nonessential Cigarette Goods Cigarette paper 2. Clothing Underwear Undershirt Short underpants Long underpants Panty Bloomers Tights Panty hose Chemise Slip Petticoat Brassiere Girdle Garter Diaper Diaper cover Sanitary shorts Nightwear Pajamas Negligee Dressing gown Nightwear Swaddling blanket Western-Style Sweater Clothes Cardigan Polo shirt T-shirt Jacket Wind jacket Vest Overcoat Raincoat Sports clothes Sports top Sports bottom Working clothes Workmen's top Overalls Business suit Suit jacket Trousers Shirt Swimming trunks One-piece dress Two-piece suit Skirt Culotte skirt Cloak Blouse Swimsuit Japanese-Style Kimono Clothes Tanzen *Tanzen: padded large-size kimono Haori *Haori: kimono jacket Hanten *Hanten: kimono short coat Hadajuban *Hadajuban: kimono underwear Hanjuban *Hanjuban: short kimono undergarment Nagajuban *Nagajuban: long kimono undergarment Japanese coat Aprons, etc. Apron Japanese-style coverall apron Makeup cape Bib 3. Clothing Accessories Socks, etc. Sock Sock cover Tabi *Tabi: Japanese sock Tabi cover