Japonica Humboldtiana 16 (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Garden Path

Photo: David M. Cobb THE GARDEN PATH MARCH 2016 • VOLUME 15 • NUMBER 3 WELCOME BACK MEMBERS SOME TIPS FOR VISITING: On March 1, just as Portland is turning to the soft breezes and opening v Construction will continue outside the Garden gates buds of spring, the Portland Japanese Garden will welcome visitors to until Spring 2017 return to our five familiar landscapes. From new leaf growth on our v The shuttle from our parking lot to the Admission Gate will Japanese maples, to pink petals appearing on our 75-year-old weeping be available Friday, Saturday, and Sundays only cherry tree, Members will have plenty of springtime sights to enjoy. v Consider taking public transportation; much of the lower Gardeners have spent the last six months getting the Garden into parking lot is being used for construction staging peak condition, and plants are well-rested and healthy—rejuvenated v Trimet Bus-Line 63 runs every hour, Monday through Friday for spring. Inside the Garden and out, this year promises to be one of v The Garden will switch to summer hours on March 13 beauty, culture, and growth. A JOURNEY FAMILIAR AND NEW Mr. Neil was born and raised on the western slope of the Rocky Members walking up the hillside path will notice a new set of stairs with Mountains in Colorado. The fantastic array of wind-swept trees in the an altered entrance into the Garden. The stair landing allows visitors landscape instilled in him a deep fascination with their beauty and the best view to observe ongoing construction, especially the progress the resilient nature of plants. -

DIJ-Mono 63 Utomo.Book

Monographien Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien Band 63, 2019 Franziska Utomo Tokyos Aufstieg zur Gourmet-Weltstadt Eine kulturhistorische Analyse Monographien aus dem Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien Band 63 2019 Monographien Band 63 Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Institut für Japanstudien der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland Direktor: Prof. Dr. Franz Waldenberger Anschrift: Jochi Kioizaka Bldg. 2F 7-1, Kioicho Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 102-0094, Japan Tel.: (03) 3222-5077 Fax: (03) 3222-5420 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.dijtokyo.org Umschlagbild: Quelle: Franziska Utomo, 2010. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dissertation der Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 2018 ISBN 978-3-86205-051-2 © IUDICIUM Verlag GmbH München 2019 Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: Totem, Inowrocław ISBN 978-3-86205-051-2 www.iudicium.de Inhaltsverzeichnis INHALTSVERZEICHNIS DANKSAGUNG . 7 SUMMARY: GOURMET CULTURE IN JAPAN – A NATION OF GOURMETS AND FOODIES. 8 1EINLEITUNG . 13 1.1 Forschungsfrage und Forschungsstand . 16 1.1.1 Forschungsfrage . 16 1.1.2 Forschungsstand . 20 1.1.2.1. Deutsch- und englischsprachige Literatur . 20 1.1.2.2. Japanischsprachige Literatur. 22 1.2 Methode und Quellen . 25 1.3 Aufbau der Arbeit . 27 2GOURMETKULTUR – EINE THEORETISCHE ANNÄHERUNG. 30 2.1 Von Gastronomen, Gourmets und Foodies – eine Begriffs- geschichte. 34 2.2 Die Distinktion . 39 2.3 Die Inszenierung: Verstand, Ästhetik und Ritual . 42 2.4 Die Reflexion: Profession, Institution und Spezialisierung . 47 2.5 Der kulinarische Rahmen . 54 3DER GOURMETDISKURS DER EDOZEIT: GRUNDLAGEN WERDEN GELEGT . -

The Lesson of the Japanese House

Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XV 275 LEARNING FROM THE PAST: THE LESSON OF THE JAPANESE HOUSE EMILIA GARDA, MARIKA MANGOSIO & LUIGI PASTORE Politecnico di Torino, Italy ABSTRACT Thanks to the great spiritual value linked to it, the Japanese house is one of the oldest and most fascinating architectural constructs of the eastern world. The religion and the environment of this region have had a central role in the evolution of the domestic spaces and in the choice of materials used. The eastern architects have kept some canons of construction that modern designers still use. These models have been source of inspiration of the greatest minds of the architectural landscape of the 20th century. The following analysis tries to understand how such cultural bases have defined construction choices, carefully describing all the spaces that characterize the domestic environment. The Japanese culture concerning daily life at home is very different from ours in the west; there is a different collocation of the spiritual value assigned to some rooms in the hierarchy of project prioritization: within the eastern mindset one should guarantee the harmony of spaces that are able to satisfy the spiritual needs of everyone that lives in that house. The Japanese house is a new world: every space is evolving thanks to its versatility. Lights and shadows coexist as they mingle with nature, another factor in understanding the ideology of Japanese architects. In the following research, besides a detailed description of the central elements, incorporates where necessary a comparison with the western world of thought. All the influences will be analysed, with a particular view to the architectural features that have influenced the Modern Movement. -

Okakura Kakuzō's Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters

Asian Review of World Histories 2:1 (January 2014), 17-45 © 2014 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.017 Okakura Kakuzō’s Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters, Hegelian Dialectics and Darwinian Evolution Masako N. RACEL Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, United States [email protected] Abstract Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), the founder of the Japan Art Institute, is best known for his proclamation, “Asia is One.” This phrase in his book, The Ideals of the East, and his connections to Bengali revolutionaries resulted in Okakura being remembered as one of Japan’s foremost Pan-Asianists. He did not, how- ever, write The Ideals of the East as political propaganda to justify Japanese aggression; he wrote it for Westerners as an exposition of Japan’s aesthetic heritage. In fact, he devoted much of his life to the preservation and promotion of Japan’s artistic heritage, giving lectures to both Japanese and Western audi- ences. This did not necessarily mean that he rejected Western philosophy and theories. A close examination of his views of both Eastern and Western art and history reveals that he was greatly influenced by Hegel’s notion of dialectics and the evolutionary theories proposed by Darwin and Spencer. Okakura viewed cross-cultural encounters to be a catalyst for change and saw his own time as a critical point where Eastern and Western history was colliding, caus- ing the evolution of both artistic cultures. Key words Okakura Kakuzō, Okakura Tenshin, Hegel, Darwin, cross-cultural encounters, Meiji Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:32:22PM via free access 18 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 2:1 (JANUARY 2014) In 1902, a man dressed in an exotic cloak and hood was seen travel- ing in India. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

16 Brightwells,Clancarty Rcad,London S0W.6. (O 1-736 6838)

Wmil THE TO—KEN SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN for theStudy and Preservation of Japanese Swords and Fittings Hon.President B.W.Robinson, M0A. ,B,Litt. Secretary: 16 Brightwells,Clancarty Rcad,London S0W.6. 1- 736 6838) xnc2ResIoENTzuna0xomoovLxnun. (o PROGRAMME NEXT MEETING Monday, OOtober 7th 1968 at The Masons Arms 9 Maddox Street 9 London 1-1.1. at 7.30 p.m. SUBJECT Annual meeting in which nominations for the new Committee will be taken, general business and fortunes of the Society discussed. Members please turn up to this important meeting 9 the evening otherwise will be a free for all, so bring along swords, tsuba, etc. for discussion, swopping or quiet corner trading. LAST. MEETING I was unable to attend this and have only reports from other members. I understand that Sidney Divers showed examples of Kesho and Sashi-kome polishes on sword blades, and also the result of a "home polish" on a blade, using correcb polishing stones obtained from Japan, I believe in sixteen different grades0 Peter Cottis gave his talk on Bows and Arrows0 I hope it may be possible to obtain notes from Peter on his talk0 Sid Diverse written remarks can his part in the meeting are as follows "As promised at our last meeting, I have brought examples of good (Sashi-Komi) and cheap (Kesho) • polishes. There are incidentally whole ranges of prices for both types of polish0 The Sashi-Komi polish makes the colour of the Yakiba almost the same as the Jihada. This does bring out all the smallest details of Nie and Nioi which would not show by the Kesho polish. -

Manusi Karate Manusi Karate "Classic"

BUDO BEST Listă de preţuri 12 decembrie 2013 www.budobest.eu [email protected] Str. Valdemar Lascarescu nr.4, sector 5, Bucuresti, cod 052378 Telefon: 0744 500 680; 0722 268 420; 021.456.25.15; Fax: 021.456.28.16 Pentru preţuri "en gros": Sumă minimă 5.000 RON Preturile se pot modifica fara preaviz (în lipsa unui contract) Stocurile produselor se pot verifica pe www.eshop-budo.ro Nr. Produs Material Culoare Marime EAN Magazin En Gros Casti Casca Clasic Piele artificiala - A9 Casca Clasic Rosu XS 6423796000018 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1258 Casca Clasic Rosu S 6423796015661 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1259 Casca Clasic Rosu M 6423796015678 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1260 Casca Clasic Rosu L 6423796015685 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1261 Casca Clasic Rosu XL 6423796015692 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1262 Casca Clasic Rosu XXL 6423796015708 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1263 Casca Clasic Albastru XS 6423796015715 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1264 Casca Clasic Albastru S 6423796015722 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1265 Casca Clasic Albastru M 6423796015739 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1266 Casca Clasic Albastru L 6423796015746 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Page 1 Piele artificiala - A1267 Casca Clasic Albastru XL 6423796015753 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1268 Casca Clasic Albastru XXL 6423796015760 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei Piele artificiala - A1269 Casca Clasic Negru XS 6423796015777 PU 126 lei 105.00 lei -

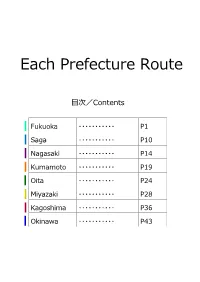

Each Prefecture Route

Each Prefecture Route 目次/Contents Fukuoka ・・・・・・・・・・・ P1 Saga ・・・・・・・・・・・ P10 Nagasaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P14 Kumamoto ・・・・・・・・・・・ P19 Oita ・・・・・・・・・・・ P24 Miyazaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P28 Kagoshima ・・・・・・・・・・・ P36 Okinawa ・・・・・・・・・・・ P43 福岡県/Fukuoka 福岡県ルート① 福岡の食と自然を巡る旅~インスタ映えする自然の名所と福岡の名産を巡る~(1 泊 2 日) Fukuoka Route① Around tour Local foods and Nature of Fukuoka ~Around tour Local speciality and Instagrammable nature sightseeing spot~ (1night 2days) ■博多駅→(地下鉄・JR 筑肥線/約 40 分)→筑前前原駅→(タクシー/約 30 分) □Hakata sta.→(Subway・JR Chikuhi line/about 40min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Taxi/about 30min.) 【糸島市/Itoshima city】 ・桜井二見ヶ浦/Sakurai-futamigaura (Scenic spot) ■(タクシー/約 30 分)→筑前前原駅→(地下鉄/約 20 分)→下山門駅→(徒歩/約 15 分) □(Taxi/about 30min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Subway/about 20min.)→Shimoyamato sta.→(About 15min. on foot) 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・生の松原・元寇防塁跡/Ikino-matsubara・Genkou bouruiato ruins (Stone wall) ■(徒歩/約 15 分)→下山門駅→(JR 筑肥線/約 5 分)→姪浜駅→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→ 能古島→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→アイランドパーク 1 □(About 15min. on foot)→Shimoyamato sta.→(JR Chikuhi line/about 5min.)→Meinohama sta.→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→ Island park 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・能古島アイランドパーク/Nokonoshima island Park ■アイランドパーク→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古島→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(西鉄バス/約 30 分)→天神 □Island park→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 30min.)→Tenjin 【天神・中州/Tenjin・Nakasu】 ・屋台/Yatai (Food stall) (宿泊/Accommodation)福岡市/Fukuoka city ■博多駅→(徒歩/約 5 分)→博多バスターミナル→(西鉄バス/約 80 分)→甘木駅→(甘木観光バス/約 20 分)→秋月→(徒歩/約 15 分) □Hakata sta.→(About 5min. on foot)→Hakata B.T.→(Nishitetsu bus/about 80min)→Amagi sta.→ (Amagi kanko bus/about 20min.)→Akizuki→(About 15min. -

Download Tour Dossier

SMALL GROUP TOURS All in Japan ALL-INCLUSIVE 12 Nights Tokyo > Hiroshima > Kyoto > Awara Onsen > Kanazawa > Tokyo Visit Himeji, Japan’s largest Tour Overview original feudal castle With all meals, transport, and luggage handling included – there’s nothing for you to do on Enjoy dinner with a performance All-In Japan but sit back and enjoy the ride. by one of Kyoto’s geisha or maiko Covering Japan’s classic destinations with a few unusual twists, this trip is full to bursting with cultural experiences designed to give you Head to the top of Mount a comprehensive and stress-free introduction Misen on Miyajima Island to Japan. Sometimes, a holiday should just be a holiday: a chance to relinquish all responsibilities, make Visit the sobering Hiroshima no decisions, and worry about absolutely Peace Park and museum nothing. On All-In Japan, you’ll do just this. Leaving every aspect of your trip to us, from your lunch to your luggage, you’ll be free to Learn about zazen meditation concentrate on immersing yourself in Japanese Kanazawa at Daianzen-ji Temple culture – safe in the knowledge that you don’t Tokyo have a penny to pay on the ground. Awara Onsen Mount Fuji Try your hand at traditional This tour is an exhilarating journey through Kyoto taiko drumming Japan’s history and traditions, from the refined geisha houses of Kyoto to Tokyo’s exuberant taiko drumming workshops. Tour the ancient temples of Kyoto, visit the biggest original castle in Japan at Himeji, and experience Hiroshima IJT ALL-INCLUSIVE TOURS zazen meditation at a beautiful temple deep in Fukui Prefecture. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Latest Japanese Sword Catalogue

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of December 23, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Upcoming Sword Shows & Sales Events Full details: http://new.uniquejapan.com/events/ 2013 YOKOSUKA NEX SPRING BAZAAR April 13th & 14th, 2013 kitchen knives for sale YOKOTA YOSC SPRING BAZAAR April 20th & 21st, 2013 Japanese swords & kitchen knives for sale OKINAWA SWORD SHOW V April 27th & 28th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN OKINAWA KAMAKURA “GOLDEN WEEKEND” SWORD SHOW VII May 4th & 5th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN KAMAKURA NEW EVENTS ARE BEING ADDED FREQUENTLY. PLEASE CHECK OUR EVENTS PAGE FOR UPDATES. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU. Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho x 2 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 -

Budotaijutsu/Ninjutsu Terms

BudoTaijutsu/Ninjutsu Terms Here is a short list of terms and their meanings. This list will be added as time goes, so ask you instructor for updates. Aite- Opponent Ganseki Nage- throwing the big rock Anatoshi- Trapping Garami- Entangle Ashiko- Foot band with spikes Gawa-Side Ate- Strike Gedan Uke- Low block Bujutsu- Horsemanship Genin- beginning ninja Barai- Sweep Genjutsu- Art of illusion Bisento- Long battlefield halberd Geri- Kick Bojutsu- Bostaff fighting Gi- Martial arts uniform Bo Ryaku- Strategy Godai- Five elements Boshi Ken- Thumb strike Gokui- Secret Budo- Martial way Gotono- using natural elements for Budoka- Student of the martial way evasion Bugie- Martial arts Gyaku- reverse Bujin- Warrior spirit Hai- Yes Bujutsu- Martial arts techniques Haibu Yori- From behind Bushi- Warrior Hajime- Begin Bushido- Way of the warrior Hajutsu- escaping techniques Chi- Earth Han- Half Chi Mon- Geography Hanbo- 3 foot staff Cho Ho- Espionage Hanbojutsu- 3 foot staff fighting Chu- Middle Happa Ken- One handed strike Chunin- Intermediate ninja Hasso- Attack Daisho- Pair of swords Heiho- Combat strategy Daito- Large sword Henka- Variation Dakenjutsu- Striking, kicking, blocking Hensojutsu- Disguise and impersonation Do- Way arts Dojo- training hall Hicho- flying bird Doko- Angry tiger Hidari- Left Dori- To capture or seize Hiji- Elbow Empi- Elbow strike Hiki- Pull Fu- Wind Hishi- Dried water chestnut caltrops Fudo Ken- immovable fist Hodoki- escapes Fudoshin- Immovable spirit Hojo- Bind, tie up Fudoza- Immovable seat Hojutsu- Firearm arts Fukiya-