Skort Title: Robert Eric Berlaua, Pros;Ruaed Iutructioa !,!!! 2!, !Eachi!C 2! Baalretball Skil.L.A Robert E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-4 Continuity Offense - Pg

1-4 Continuity Offense - pg. 1 1-4 Continuity Offense Table of Contents 1. Set-up Game 2 2. Wing Entry 3 3. Post Entry 5 4. Dribble Entry 6 All Contents Proprietary 1-4 Continuity Offense - pg. 2 Set-up Game 1-4 From Stack Alignment 2 3 2 and 3 Cross and Posts Flash to Elbow 4 5 Timing Critical 1 1-4 From Diamond Alignment 2 man go off either side and 3 goes opposite 3 5 4 2 1 1-4 From Box Set 3 2 Posts Downscreen and Flash to Elbow 5 4 1 All Contents Proprietary 1-4 Continuity Offense - pg. 3 Wing Entry Pass to either wing after set-up game to 1-4 2 3 5 4 1 Ball side post sprints to top of the key Weakside post cuts behind defense to 1st hash above block Point Guard cuts through the elbow and waits for ball reversal opposite wing cheats in for block to block screen 3 5 4 2 1 Key to the play is how quickly we can reverse the ball from wing to wing. The ball pust be passed from 2 to 1 as quickly as possible. 1 3 5 2 4 Small on Big Cross-Screen Post Player must wait to receive screen and will always go low off of the 3 5 screen. Guard then receives downscreen from post player 1 2 4 If a shot is not available, the posts immediately flash to elbows and offense resumes 5 4 2 1 3 All Contents Proprietary 1-4 Continuity Offense - pg. -

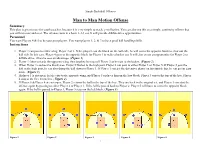

Man to Man Motion Offense Summary This Play Is Great to Use for Youth Coaches, Because It Is Very Simple to Teach, Yet Effective

Simple Baskeball Offenses Man to Man Motion Offense Summary This play is great to use for youth coaches, because it is very simple to teach, yet effective. You can also use this as a simple, continuity offense that you will run over and over. The offense starts in a basic 1-3-1 set. It will provide dribble-drive opportunities. Personnel You want Players 4 & 5 to be your post players. You want players 1, 2, & 3 to have good ball handling skills. Instructions 1. Player 1 can pass to either wing, Player 2 or 3. If the player is on the block on the ball side, he will cut to the opposite block to clear out the ball side. In this case, Player 4 goes to the opposite block for Player 1 to make a basket cut. It will also create an opportunity for Player 2 to dribble drive, if he/she sees an advantage. (Figure 1) 2. Player 1 fakes towards the opposite wing, then brushes his man off Player 5 as he cuts to the basket. (Figure 2) 3. When Player 1 reaches the block area, Player 5 flashes to the high post. Player 2 can pass to either Player 1 or Player 5. If Player 5 gets the ball in the high post, he can also dump the ball down to Player 1. If Player 1 can get the defensive player on his outside hip, he can get an easy score. (Figure 3) 4. If player 1 is not open, he/she cuts to the opposite wing, and Player 5 replaces him on the low block. -

Double / Triple Screen Offense Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense

Newsletter Double / triple screen offense Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense The Double / Triple Screen Offense is a "play call" for us. Our primary offense is the dribble motion, but we will mix in some sets and this continuity offense. I have chosen, for now, this Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense. Our players run there normal lanes. #5 always runs down the middle of the court and then to the block away from the ball. We run to these alignments so that we can start our Dribble Motion....if not, we are able to begin our Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense with a "play call". Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense BASIC CONTINUITY #1 will dribble up into the right wing area. As #1 dribbles in... • #2 cuts to the ball side low block • #4 cuts to the FT line ball side elbow • #3 cuts to the back side FT line elbow • #5 steps out a few feet from the opposite block Double / Triple Screen Continuity Offense BASIC CONTINUITY From here, we will begin everybody's favorite..."America's Play", by screening across with #2 for #5. #5 has stepped out a few feet from the lane so that he will have more room to setup his defender. #3 and #4 are ready to set a double down screen for #2. Since #3 and #4 will be setting a triple screen immediately after this screen, we ask them to stay out of the lane until #5 comes off of the screen from #2. If #5 is open, #1 will deliver the ball to the low post. -

CHARLES R. SMITH, JR. Story & Libretto

Our missions is: • to create new operas that enchant, challenge, and inspire our diverse global community & encourage new ways of seeing our world; • to make opera relevant to our 21st century world, nation, and communities We do this: • by engaging new audiences & new generations in the process and the performance of the opera; • by partnering with producers and community organizations to extend our reach both within and far outside the walls of the opera house. Opera was first created as a theatrical form for the people. Our mission is to help keep it that way. Ardea Arts, Inc. is a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) corporation. All donations are tax-deductible to the full extent allowed by law. [email protected] // 463 BROOME ST, NEW YORK, NY 10013 // TEL 212.431.7039 ARDEAARTS.COM WWW.ARDEAARTS.COM/BOUNCE Promo Pack: www.artistecard.com/bounce Produced and developed by ARDEA ARTS // Development Partner UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY OPERA THEATRE 463 Broome St // New York, NY 10013 // Tel 212.431.7039 // www.ArdeaArts.com ABOUT THE SHOW BOUNCE Promo Kit: www.artistecard.com/bounce “...a new form of Opera and a cast of wonderful young people...” From an Audience Member at our March Presentation 2017 Produced and developed by ARDEA ARTS // Development Partner UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY OPERA THEATRE 463 Broome St // New York, NY 10013 // Tel 212.431.7039 // www.ArdeaArts.com CREDITS BOUNCE THE BASKETBALL OPERA Concept & Direction: Grethe Barrett Holby Story & Libretto: Charles R. Smith, Jr. Lead Composer: Glen Roven Additional Music: Tomás Doncker Basketball EDM Tracks: Ansel Elgort aka DJ Ansolo Co-Producer & Conductor: Everett McCorvey Location: Basketball courts or large flexible theatrical space. -

John Calipari Dribble Drive Motion 5 Offense

John Calipari Dribble Drive Motion 5 Offense It's been a while since I've revisted the dribble drive offense with any depth and since John Calipari's DVDs have finally debuted, I thought I would release the hounds with Calipari's version of Walberg's system. There a few continuity-based halfcourt sets that Calipari has added to the system while at Memphis and will likely use at Kentucky. It will take a few posts to get them all through, but this is the first one. Motion 5 To preface the diagrams, remember that at all times the goal of the offense is to get to the rim. Once a player gets into the 'rack zone', DDM terminology for 'in the key', the goal is to dunk it (or layup). Ordinarily, O5 is down low, but in this case O4 is down low and O5 is up top. The continuity starts with O1 trying to beat his defender off the dribble. If he cannot get past, he passes to O2 who comes straight up from the corner. O1 loop cuts to the corner after the pass O2 attempts to take his defender off the dribble by turning the corner with a middle drive. O5 relocates cross the lane up top. O3 steps up out of the corner to the opposite free- throw line extended. O4 relocates block to block. If O2 is unable to turn the corner, he can find O4. If O4 is not open, then the pass goes to O3, The same action repeats except with O3 driving and O1 in the opposite corner coming up to the opposite free-throw line extended, Now, you can run that action over and over again, just like any traditional continuity offense like a flex, etc. -

Buffalo Continuity This Continuity Offense Was Developed from a Set Play Ran by Buffalo High School in Minnesota

Buffalo Continuity This continuity offense was developed from a set play ran by Buffalo high school in Minnesota. I was an assistant coach for a team that played them in the playoffs and this was one of the set plays our scouts sent to us. I really liked the action and just tweaked it to make it a continuity offense. In all reality, I am a motion offense guy through and through. But I’m not against using set plays or simple continuity offenses from time to time. This is one I feel I could implement easily and employ if need be. I’m going to add some thoughts and notes in on the possible little things you could add here and there. Take what you want, throw what you don’t! Make this offense your own. Basic Overview For the diagrams, the offense starts out in a 1-2-2 look. I will have a section in the end on getting into it out of different alignments. The point guard brings the down and picks a side by dribbling at one of the wings. As the wing sees that they are being dribbled at, they should cut to the basket, across the lane and to the opposite corner of the floor. The backside post player can set a flair screen initially for him if you desire, especially if he is a shooter. The post player on the back side should flash up to the back side high post as should the ball side post player. The ball side post player, however, can wait a second or two and look for a post up if you desire. -

Dribble Motion Offense.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction Pages 3 — 6 Training Aids Pages 7 — 12 Warming Up Pages 13 — 15 Offensive Alignment and Rules Pages 16 — 22 Specials Pages 23 — 35 Half Court Breakdown Drills Pages 36 — 47 Full Court Breakdown Drills Pages 48 — 67 Notes from the Web Pages 68 — 143 Implementing The Dribble Motion Offense Introduction PagePage 3 3 Like many of you, when a new offensive system comes along, I make every effort to gather as much information as I can before making a decision on whether or not to make a change in my current offensive arsenal. When you hear coaches talk about the Dribble Motion Offense, you hear them make rather bold statements like, “This offense will revolutionize the game, much like the spread or motion offense did when it was introduced.” Those kinds of statements certainly get your attention. It got mine. And I set out to learn all I could about this offense, knowing full well that if this is going to revolutionize the game, than I better learn all I can about it, because I’m going to face it eventually. That is exactly how I came across this offense. Not necessarily with the intention of using it, but rather to learn the intricacies of the system so that I would be better equipped to defend it. Plain and simple. By explaining to you why I like this system, I think it would be best to look at what others feel may be the weaknesses of this system, and then give you my opinion and how I hope to counter some of the real and perceived “drawbacks” of this system. -

Twelve Great Basketball Offenses. INSTITUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, Reston, VA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 217.005 SP 020 174 AUTHOR Healey, William A.; Hartley, Joseph W. TITLE Twelve Great Basketball Offenses. INSTITUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, Reston, VA. National Association for Sport and Physical Education. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 306p. AVAILABLE FROM American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 1900 Association Drive, Reston, VA 22091 (Stock Number: 245-27032; $10.95). EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Athletes; Athletic Coaches; *Basketball; Competition IDENTIFIERS *Basketball Offense ABSTRACT Features and merits of twelve offensive basketball patterns are presented in this volume. Plays described are: (1) single pivot-post offense; (2) double pivot-post offense; (3) weak-side cutter series (reverse action offense); (4) 1-3-1 offense (hi-lo offense); (5) Illinois continuity offense; (6) rotation offense; (7) shuffle offense; (8) pick and roll offense; (9) fast break; (10) zone offense; (11) deep screen motion offense; and (12) triangle-4 offense. A summary of the origin and development of each play is given, followed by a discussion of basic moves, patterns, and details of step-by-step and phase movements. Diagrams illustrate options and variations discussed in the teat. (FG) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** Twelve Great Basketball Offenses Dr. William A. Healey and Joseph W. Hartley with a foreword by Norman Sloan Sponsored by the National Association for Sport and Physical Education an association of The American Alliance for U ti DEPAISMIENT OF EDUCATION Health, Physical Education, "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION MATERIAL IN MICROFICHEONLY EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Recreation and Dance INFORMATION BY CENTER (ERIC) HAS SEEN GRANTED 0 0 This document hasbeen recroduesd as from Me person ororsenfsation W. -

KENNESAW STATE OWLS 2018-19 Men’S Basketball GAME NOTES

KENNESAW STATE OWLS 2018-19 men’s basketball GAME NOTES » KENNESAW STATE VS OGLETHORPE GAME 1 | NOVEMBER 7 | 7:30 P.M. | CONVOCATION CENTER | KEnnESAW, GA. » 2017-18 SCHEDULE KENNESAW STATE vs OGLETHORPE RECORD: 0-0, 0-0 RECORD: 0-0, 0-0 » NOVEMBER COACH: AL SKINNER COACH: PHILIP PONDER KSU: 4TH SEasON (35-58) OU: 16TH SEasON (214-182) 1 Clayton State (EXH) W, 81-78 CAREER: 26TH SEasON (420-349) CAREER: 16TH SEasON (214-182) 7 Oglethorpe 7:30 p.m. 9 at Kansas State 7 p.m. 12 at Samford 8 p.m. » THE BREAKDOWN 16 vs. Missouri^ 4 p.m. TV .............................................................................................................................................ESPN+ 17/18 vs. Oregon State/Old Dominion^ TBD Radio ................................................................................................................................Owl Radio 19 vs. TBD^ TBD 24 Belmont 4 p.m. Live Stats ..................................................................................................................... KSUOwls.com 27 at Georgia 7 p.m. Twitter ..................................................................................................................@KSUOwlsMBB Series History ..........................................................................................Oglethorpe leads 4-2 » DECEMBER Last Meeting ............................................ 2/20/88, Kennesaw State 89, Oglethorpe 62 1 Hofstra 2 p.m. 13 at Gardner-Webb 5:30 p.m. » TOP STORYLINES 15 Tennesee Tech 4 p.m. 18 Elon 7 p.m. » The Kennesaw State -

New York Schedule

USA BASKETBALL NEW YORK COACH ACADEMY PRESENTED BY NIKE TIME LOCATION SATURDAY SESSIONS 9:00am-9:15am Main Gym Welcome to the Gold Standard - Jay Demings, USA Basketball Perimeter Player Development 9:20am-10:10am Main Gym - Mike Jones, DeMatha Catholic High School 10:15am-11:00am Main Gym Smart Shooting to Impact the Game - Heather Macy, East Carolina University USAB.COM @USABYOUTH AUDITORIUM MAIN GYM Auditorium & 11:10am-11:55am Building a Program From the Ground Up Improving Athleticism in Youth Athletes Main Gym - Kate Achter, Loyola University Chicago - Jason Papalio & Rahsaan Robinson 12:00pm-1:00pm Cafeteria Networking Lunch Pressure Defense Practice Drills 1:05pm-1:55pm Main Gym - Greg Herenda, Fairleigh Dickinson University Developing Youth Through Basketball 2:05pm-2:50pm Auditorium - Don Showalter, USA Basketball MAIN GYM AUDITORIUM Auditorium & Building Your Man-to-Man Defense Baseline Scoring Plays 3:00pm-3:45pm - Bob Cimmino, Mount Vernon High Main Gym - Nick Cammarano, Frank Antonides School School Practice Design: Conceptual and Practical 3:55pm-4:40pm Main Gym - Brian McCormick, Playmakers Basketball Development League & Broward College America’s New Continuity Offense 4:50pm-5:35pm Main Gym - Raphael Chillious, University of Connecticut TIME LOCATION SUNDAY SESSIONS 8:30am-9:00am Cafeteria Catered Breakfast 9:00am-9:45am Auditorium Culture Over All PROMOTE, GROW AND ELEVATE THE GAME ANDELEVATE GROW PROMOTE, - Joe Mantegna, Blair Academy The State of Youth Basketball in the United States 9:55am-10:40am Auditorium - Jay Demings, USA Basketball 10:50am-11:35am Main Gym Building a Motion Offense - King Rice, Monmouth University Developing Individual Skills in a Team Setting 11:45am-12:30pm Main Gym - Jim Engles, Columbia University MAY 20-21, 2017. -

Drills and Skills Manual

Drills and skills manual 1 GUIDELINES FOR JUNIOR PLAYER DEVELOPMENT E = Exposed P = Proficient M = Mastered U/14 U16 U18 U20 10-13yrs 14-15yrs 16-17yrs 18 & up BODY MOVEMENT FUNDAMENTALS 1. Triple threat position (every possession) P/M M M M 2. Running (controlled) P M M M 3. Changing direction P M M M 4. Jump stop M M M M 5. Stride stop-general M M M M 6. Stride stop leading to shot E P M M 7. Jumping (from triple threat position) M M M M 8. Jumping (on the move i.e. layup) P M M M 9. Shuffling M M M M 10. Drop step M M M M 11. Pivoting P M M M PASSING & RECEIVING 1. Grip (before passing/upon receiving) P M M M 2. Two hand chest pass M M M M 3. Two hand bounce pass M M M M 4. Two hand overhead pass P M M M 5. Baseball pass E P M M 6. Hook pass E P M M 7. One hand push pass E P M M 8. Hand off to cutter E P M M 9. Lob pass - E P M 10. Receiving — balanced, give target, P M M M work to get open, meet pass, eyes on ball, catch softly on fingers, tuck ball away, square up BALL HANDLING 1. Ball familiarity drills P M M M 2 DRIBBLING U14 U16 U18 U20 Strong Hand 1. Control dribble (stationary) M M M M 2. Control dribble (moving) M M M M 3. -

Climb the "Ladder System" to New School Program Heights by Bruce Brown, Athletic Director and Former Boys Head Coach, Uniontown Lake High School, Uniontown, Ohio

Climb The "Ladder System" To New School Program Heights By Bruce Brown, Athletic Director and Former Boys Head Coach, Uniontown Lake High School, Uniontown, Ohio OVER THE COURSE of 25 years in coaching at the high FEEDER-SYSTEM OBJECTIVES school and college levels, I've observed several "musts" Junior Varsity, Varsity Level. The objectives and goals of which should be in place for a basketball program to realize the junior varsity program should be identical to those of optimal success. the varsity level. Emphasis should be on preparing players One key ingredient is the establishment of a coordinated, to perform at the varsity caliber of competition. systematic format to teach proper skills and strategies View these players in terms of, "Can this player help us at throughout the feeder levels. The creation of a strong local the varsity level by the time he or she is a senior?" feeder system will pay huge dividends toward developing a winning high school basketball program. Junior High School Level. The objectives and goals of the In 1974, our program developed a "ladder" approach to seventh-, eighth- and ninth-grade programs should be con- address the needs of our school's basketball system. With sistent with the varsity and junior varsity levels. You need to minor tweaking and adjustments over the years, this basic also add the offensive and defensive philosophies of your system has been an excellent tool for maintaining continuity basketball program. and teaching essential skills to our players as they grow old- Include as many individuals in your program as possible er and develop.