Religiosity and Delinquency Author(S): Sergej Flere Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 2

Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 2 | 1 Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 2 Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences IIASS is a double blind peer review academic journal published 3 times yearly (January, May, September) covering different social sciences: | 2 political science, sociology, economy, public administration, law, management, communication science, psychology and education. IIASS has started as a SIdip – Slovenian Association for Innovative Political Science journal and is being published by ERUDIO Center for Higher Education. Typeset This journal was typeset in 11 pt. Arial, Italic, Bold, and Bold Italic; the headlines were typeset in 14 pt. Arial, Bold Abstracting and Indexing services COBISS, International Political Science Abstracts, CSA Worldwide Political Science Abstracts, CSA Sociological Abstracts, PAIS International, DOAJ, Google scholar. Publication Data: ERUDIO Education Center Innovative issues and approaches in social sciences, 2020, vol. 13, no. 2 ISSN 1855-0541 Additional information: www.iiass.com Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 2 DEVELOPING A POSITIVE ATTITUDE OF PUPILS TOWARDS CONTEMPORARY FINE ARTS | 60 Katja Kozjek Varl1, Matjaž Duh 2 Abstract The article presents the implementation of fine arts lessons in the ninth grade of elementary school (14 - 15 years old pupils), which was prepared in accordance with the guidelines of contemporary fine arts pedagogical practice, with emphasis on contemporary fine arts. The study compared pupils' attitudes to contemporary fine arts before and after working with contemporary fine arts and recorded the course of teaching at the level of contemporary visual arts practices. We were interested if the incorporation of contemporary artistic practices into the process of teaching fine arts to pupils is an impetus for the formation of their own ideas, and thus for development of a critical attitude and encouragement of individual’s critical thinking. -

University of Mostar

Faculty of Economics University of Mostar ,*. { i. I "-",* ,:J fl I NTE RNATIONAL CON FE RENCE Proceedings 1,1,-1,2 November 2011 Mostar; Bosnia and Herzegovina Tige Proceedings of the hternational Conference,Bconomic Theory and Practice: Meeting the New Challenges" Publisher Faculty of Economics University of Mostar Matice hrvatske bb, 8S 000 Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina http://ef.sve-mo.bal For the Publisher Prof. Dr' Brano Marki6, Acting Dean Layout Mirela Mabi6 Cover Design FramZiral d.o.o. PttzaAluminij bb, Mostar, BiH Printed by FramZiral d.o.o. P:utzaAluminij bb, Mostm, BiH Number of copies 300 printed Copyright @ 2011 by Faculty of Economics University of Mostar All rights reserved. No part of this publication rnay be reproduced stored in a retrieval system, or tansmitte4 in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher' ISSN 2233- 0267 Scientific Committee President of the Scientific Committee Brano Markid - Faculty of Economics, University of Mostar, BiH Vice-Presidents of the Scientific Committee Zeljko Suman - Faculty of Economics, University of Mostar, BiH Antonis Simintiras - School of Business and Economics, Swansea University, UK Members Mate Babi6 - Faculty of Economics, Zagreb, Croatia Marika Baseska-Gjorgjieska - Faculty of Economics, Prilep, FRY Macedonia Marin Buble - Faculty of Economics, Split, Croatia Giuseppe Burgio - University of Rome "La Sapierza", EuroSapienza,ltaly Muris Cidi6 - Faculty of Economics, Sarajevo, BiH DraLena Ga5par - Faculty of Economics, University of Mostar, -

WORKING PAPER No. 88, 2015

KEY COMMON AND COMPLEMENTARY COMPETENCIES OF THE CROSS-BORDER REGION SLOVENIA-AUSTRIA Damjan Kavaš Sonja Uršič Klemen Koman WORKING PAPER No. 88, 2015 December, 2015 Key Common and Complementary Competencies of the Cross-Border Region Slovenia- Austria Damjan Kavaš1, Sonja Uršič2, Klemen Koman3 KEY COMMON AND COMPLEMENTARY COMPETENCIES OF THE CROSS-BORDER REGION SLOVENIA-AUSTRIA Printed by the Institute for Economic Research – IER Copyright retained by the authors. Number of copies – 50 pieces WORKING PAPER No. 88, 2015 Editor of the WP series: Boris Majcen. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 332.1:339.92 KAVAŠ, Damjan, 1970- Key common and complementary competencies of the cross-border region Slovenia- Austria / Damjan Kavaš, Sonja Uršič, Klemen Koman. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za ekonomska raziskovanja = Institute for Economic Research, 2015. - (Working paper / Inštitut za ekonomska raziskovanja, ISSN 1581-8063 ; no. 88) ISBN 978-961-6906-36-4 1. Uršič, Sonja, 1976- 2. Koman, Klemen 282787840 1 Institute for Economic Research, Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 2 Institute for Economic Research, Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 3 Institute for Economic Research, Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] Abstract This working paper presents the results of the analysis of capacities of the cross-border region Slovenia-Austria and the subsequent identification of its key common and complementary competencies. The paper was triggered by the fact that past cross-border co-operation projects lacked strategic focus on long-term key development priorities (i.e. key common and complementary competencies) of the co-operation area. We start our analysis by presenting the socio-economic development in the regions concerned and complement the analysis with the description of global challenges, Europe 2020 targets as well as key impacting policies and key (recent) trends at national and regional level. -

University of Mostar – Workshop 06.10.2020 – 07.10.2020

University of Mostar – Workshop 06.10.2020 – 07.10.2020 Venue: Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology, University of Mostar. Biskupa Čule bb 88 000 Mostar On line: Zoom platform WP 2, activities set by 2.1: Improved competences of use of ICT in agriculture Theme: 2nd training with attention on mobile applications, robotics and drones in agriculture Trainee: participants from partner's institutions from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro. List of participants is added. Additional trainee followed training on Zoom. MEETING MINUTES Training with aim of improving competences on use of ICT in agriculture was scheduled by project application to be held in Podgorica Montenegro and organized by University of Donja Gorica in summer of 2020. Due to the special measures introduced since COVID 19 virus pandemic we were forced to change plans. Since majority of partners are from Bosnia and Herzegovina it was decided to relocate training in Mostar with presenters from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Slovenia and Netherlands. Training was held in October 6th and 7th and also streamed on ZOOM platforms. On this way it was possible to participate even if person could not attend training in person. In a line with that some of the presentations were done in person and other were presented from distance by Zoom platform. The workshop was intended primarily for teaching staff and students in master and doctoral studies of higher education institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, but also for other interested individuals, primarily participants in the VIRAL project and representatives of the agribusiness sector. Workshop agenda is added to the report. -

University of Zagreb Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Vlado Glavinić (University of Zagreb, Croatia) EDITORIAL BOARD Maria Victoria Bueno Delgado (Technical University of Cartagena, Spain) Andrea Kő (Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary) Shifeng Liu (Beijing Jiaotong University, China) Instructions to Authors Zongmin Ma (Northeastern University, Shenyang, China) Aniket Mahanti (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Robert Manger (University of Zagreb, Croatia) Tanja Mitrovic (University of Canterbury, New Zealand) Richard Picking (Glyndŵr University, Wales, United Kingdom) General • Manuscripts should contain the usual sections as Slobodan Ribarić (University of Zagreb, Croatia) found in scientifi c publications (mandatory Introduc- Richard Torkar (Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden) tion, and Conclusion). Runtong Zhang (Beijing Jiaotong University, China) When preparing a manuscript, please strictly comply Hong Zhao (Fairleigh Dickinson University, USA) with the Journal guidelines, as well as with the ethic stan- • List of symbols and/or abbreviations – if non-com- EDITOR FOR dards of scientifi c publishing. mon symbols or abbreviations are used in the text, SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY Richard Torkar (Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden) you can add a list with explanations. In the running EDITOR FOR Manuscripts should be written in English. If English is text, each abbreviation should be explained the fi rst BIBLIOMETRICS Jadranka Stojanovski (University of Zadar, Croatia) not your native language, please arrange for the text to time it occurs. ASSOCIATE EDITORS Siniša Šegvić (University of Zagreb, Croatia) be reviewed by a professional editing service. Maintain a Jan Šnajder (University of Zagreb, Croatia) consistent style with regard to spelling (either UK or US Mincong Tang (Beijing Jiaotong University, China) English), punctuation, nomenclature, symbols, etc. -

UNIVERSITY of PRISHTINA the University-History

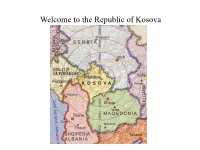

Welcome to the Republic of Kosova UNIVERSITY OF PRISHTINA The University-History • The University of Prishtina was founded by the Law on the Foundation of the University of Prishtina, which was passed by the Assembly of the Socialist Province of Kosova on 18 November 1969. • The foundation of the University of Prishtina was a historical event for Kosova’s population, and especially for the Albanian nation. The Foundation Assembly of the University of Prishtina was held on 13 February 1970. • Two days later, on 15 February 1970 the Ceremonial Meeting of the Assembly was held in which the 15 February was proclaimed The Day of the University of Prishtina. • The University of Prishtina (UP), similar to other universities in the world, conveys unique responsibilities in professional training and research guidance, which are determinant for the development of the industry and trade, infra-structure, and society. • UP has started in 2001 the reforming of all academic levels in accordance with the Bologna Declaration, aiming the integration into the European Higher Education System. Facts and Figures 17 Faculties Bachelor studies – 38533 students Master studies – 10047 students PhD studies – 152 students ____________________________ Total number of students: 48732 Total number of academic staff: 1021 Visiting professors: 885 Total number of teaching assistants: 396 Administrative staff: 399 Goals • Internationalization • Integration of Kosova HE in EU • Harmonization of study programmes of the Bologna Process • Full implementation of ECTS • Participation -

Sanofi-Synthelabo Annual Report 2001

annual report Contents Group profile page 1 Chaiman’s message page 3 Key figures page 6 Stock exchange information page 8 Corporate governance page 11 Management Committee page 12 Prioritizing R&D and growth so as to drive back disease Research and development page 16 Medicine portfolio page 22 International organization page 36 2001 Annual report 2001 Annual report Working for the long term, a company - which respects people and their environment Ethics page 46 page 50 Sanofi-Synthélabo Human resources policy Health Safety Environment policy page 54 This annual report was designed and produced by: The Sanofi-Synthélabo Corporate Communications and Finance Departments and the Harrison&Wolf Agency. Photo credits: Getty Images / Barry Rosenthal • Getty Images / Steve Rowell • INSERM / J.T. Vilquin • CNRS / F. Livolant • Photothèque Sanofi-Synthélabo • Photothèque Sanofi-Synthélabo Recherche Montpellier • Publicis Conseil / Adollo Fiori • Luc Benevello • Olivier Culmann • Michel Fainsilber • Vincent Godeau • Florent de La Tullaye • Patrick Lefevre • Gilles Leimdorfer • Martial Lorcet • Fleur Martin Laprade • Patrice Maurein • Bernadette Müller • Laurent Ortal • Harutiun Poladian Neto • Anne-Marie Réjior • Marie Simonnot • Denys Turrier • The photographs which illustrate this document feature Sanofi-Synthélabo employees: we would like to thank them for their contribution. 395 030 844 R.C.S. Paris Group Profile 2nd pharmaceutical group in France 7th pharmaceutical group in Europe One of the world’s top 20 pharmaceutical groups Four areas of specialization Sanofi-Synthélabo has a core group of four therapeutic areas: • Cardiovascular / thrombosis • Central nervous system • Internal medicine • Oncology This targeted specialization enables the group to be a significant player 2001 Annual report 2001 Annual report in each of these areas. -

Sensory Evaluation of Dry Persimmons of the Tipo (Diospyros Kaki L

Agricultura 17: No 1-2: 1-8(2020) https://doi.org/10.18690/agricultura.17.1-2.1-8(2020) Sensory Evaluation of Dry Persimmons of the Tipo (Diospyros kaki L. f.) Variety Andrej Vogrin*, Petra Marko, Tatjana Unuk University of Maribor, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Pivola 10, 2311 Hoče, Slovenia ABSTRACT The study carried out at the Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences of the University of Maribor aimed to evaluate the attractiveness of dried persimmon fruit depending on the method of preparing the fruit for drying. The methods varied in terms of the ripeness of the fruit, the thickness and shape of the slices, the presence of seeds (in fertilised fruits) and the presence of peel. Sensory evaluation was performed by students and staff, using a hedonic scale, where evaluators evaluated the appearance (shape and colour) and taste (sugar-acid ratio, texture, tartness, presence of fruit peel, and general impression) of the fruit. Dried unfertilized persimmons, with the presence of peel, cut into 3 mm thick slices, were given the highest score for overall attractiveness. In terms of taste, unfertilised, peeled persimmon slices scored the highest. Considering all parameters, the results showed that unfertilised persimmons were more suitable for drying and that the presence of the peel was not a disturbing factor for consumers. Key words: Persimmon, fruit drying, hedonic sensory evaluation INTRODUCTION The objective of the study performed at the Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences of the University of Maribor Persimmon is a fruit that grows in subtropical and was to determine how the method of preparation of fresh moderately warm climate zones. -

Meet Slovenian Consul General Jure Žmauc

Published September 7, 2009 E-mail: [email protected] Est. MMVII Meet Slovenian Consul General Jure Žmauc One week on the job and he has already fielded a number interviews, enjoyed a performance of the Cleveland based dance group Folklorna Skupina Kres, attended the Cleveland Council of World Affairs lecture "Transatlantic Agenda" by Dr. Klaus Scharioth, German Ambassador to the United States and had a Slovenian-style fish fry at the Slovenian Workmen's Home. Jure’s wife Janja with children Nika 17and Ajaž 12 will arrive in the United States later this month. The Žmauc family has plans to live in the Cleveland suburb Kirtland, Ohio. Consul General Žmauc can be reached by telephone at 216-589-9220 or email [email protected] FilmAbove: Consul General Jure Žmauc in the Cleveland Slovenian Consulate General. Photo by Phil Hrvatin September 4, 2009 Group photo: Cleveland's new Consul General from Slovenia, Jure Žmauc, enjoyed his first Slovenian-style fish fry at the Slovenian Workmen's Home within days of his arrival. Consul Žmauc met members of the city's Slovenian community and learned about the variety of upcoming events on the Slovenian social calendar. From left: Joe Valenčič, Jure Žmauc, Charles Ipavec, Bob Dolgan, Cilka Dolgan, Barbara Strumbly and Charlie Ipavec.( submitted by Joe Valenčič ) Phil Hrvatin Senior Editor Tim Percic Creative Design Mr. Jure Žmauc Consul General of the Republic of Slovenia in Cleveland On August 22, 2009, The Republic of Slovenia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs relieved Consul General Dr. Zvone Žigon from his official duties in Cleveland, OH. -

464018 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..20

Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems Volume 42 Series editor Janusz Kacprzyk, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The series “Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems” publishes the latest developments in Networks and Systems—quickly, informally and with high quality. Original research reported in proceedings and post-proceedings represents the core of LNNS. Volumes published in LNNS embrace all aspects and subfields of, as well as new challenges in, Networks and Systems. The series contains proceedings and edited volumes in systems and networks, spanning the areas of Cyber-Physical Systems, Autonomous Systems, Sensor Networks, Control Systems, Energy Systems, Automotive Systems, Biological Systems, Vehicular Networking and Connected Vehicles, Aerospace Systems, Automation, Manufacturing, Smart Grids, Nonlinear Systems, Power Systems, Robotics, Social Systems, Economic Systems and other. Of particular value to both the contributors and the readership are the short publication timeframe and the world-wide distribution and exposure which enable both a wide and rapid dissemination of research output. The series covers the theory, applications, and perspectives on the state of the art and future developments relevant to systems and networks, decision making, control, complex processes and related areas, as embedded in the fields of interdisciplinary and applied sciences, engineering, computer science, physics, economics, social, and life sciences, as well as the paradigms and methodologies behind them. Advisory -

Via Urbium 06

Dravska 01 Pekrska gorca 02 Bresterniško jezero 03 Pustolovska 04 Forma Viva 05 TIC Maribor 5 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos TIC Maribor 24 km srednje zahtevna/intermediate/mittelschwer TIC Maribor 14 km srednje zahtevna/intermediate/mittelschwer TIC Maribor 17 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos TIC Maribor 16 km nezahtevna/undemanding/anspruchslos • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Potek poti / Route / Verlauf des Weges: • Opis / Description / Beschreibung: Forma viva predstavlja v Mariboru pomemben TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg Svobode – Grajski trg – Slovenska ul. – Gosposka ul. – Glavni trg – Koroška cesta TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg Svobode – Grajski trg – Slovenska ul. – Gosposka ul. – Glavni trg – Koroška TIC Partizanska cesta – Trg svobode – Trg generala Maistra – Ul. heroja Staneta – Maistrova ul. – Prešernova TIC Partizanska cesta – Titova cesta (Titov most) – Pobreška cesta – Čufarjeva cesta – Ul. Veljka Vlahoviča – umetniški poseg v urbano strukturo mesta, ki ponuja izjemno atraktiven vpogled v skrivnosti in različne značaje mesta Vsak udeleženec vozi po predlaganih poteh na lastno odgovornost in - Splavarski prehod – Ob bregu (Lent) – Studenška brv – obrežje Drave (bank of the river Drava, das Ufer der cesta – Splavarski prehod – Ob bregu (Lent) – Studenška brv – obrežje Drave (bank of the river Drava, das ul. – Tomšičeva ul. – Ribniška ul. – Za tremi ribniki (Ribniško selo) – Vinarje – Vrbanska cesta – Kamnica – Cesta XIV. divizije – Kosovelova ul. (Stražun) – Štrekljeva ul. – Janševa ul. – Ptujska cesta – Cesta Proletarskih Maribor – tako v mestnem jedru kot tudi v posameznih mestnih četrtih. Z željo opozoriti na to dragoceno kulturno Drau) – Dvoetažni most – Oreško nabrežje – Mlinska ul. – Partizanska cesta – TIC Partizanska cesta Ufer der Drau) – Obrežna ul. -

Societal Risk Perception by Laypersons Living in Venezuela

Societal risk perception by laypersons living in Venezuela. A Latin countries comparison* La percepción de riesgo social por laicos que viven en Venezuela. Una comparación entre países Latinos Received: 23 July 2015 | Accepted: 01 December 2015 Ana Gabriela Guédez** Universidad de Jean Jaurès, Francia ABSTRACT The present study presents the mean risk magnitude judgments on 91 activities, substances, and technologies expressed by Venezuelan adults living in the two main cities of this country: Caracas and Maracaibo. These judgments were compared methodically with findings on other samples of previous studies, namely four other Latin countries: France, Spain, Brazil, and Portugal. The aim of this study was to structure the cross-country differences in risk perception between the aforementioned countries and Venezuela using cluster analysis. A 91-hazard x 5 country matrix was created. Two main clusters were found. The Economically and Socially Challenging group (Venezuela and Portugal) and the Western Europe group (France and Spain). Brazil was situated closer to the **Departamento de Psicología Cognitiva. E-mail: Venezuelan and Portugal cluster than was the Western Europe group. [email protected] The common denominator in the Economically and Socially Challenging group can be the economic and social problems that both of these countries struggle against. It was reasonable that Brazil was closer to this cluster, given its similarities to both countries (in geographical and cultural terms). More explanations for these clusters were presented in the discussion. Finally, some recommendations and limitations are also presented and more research in this field is suggested as well. Keywords risk perception, social psychology, latin countries, Venezuela.