Impact of Daily Temperature Fluctuations on Dengue Virus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Diversity of Dengue Virus in Clinical Specimens from Bangkok

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Article Genetic Diversity of Dengue Virus in Clinical Specimens from Bangkok, Thailand, during 2018–2020: Co-Circulation of All Four Serotypes with Multiple Genotypes and/or Clades Kanaporn Poltep 1,2,3 , Juthamas Phadungsombat 2,4 , Emi E. Nakayama 2,4 , Nathamon Kosoltanapiwat 1 , Borimas Hanboonkunupakarn 5, Witthawat Wiriyarat 3, Tatsuo Shioda 2,4,* and Pornsawan Leaungwutiwong 1,* 1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (N.K.) 2 Mahidol-Osaka Center for Infectious Diseases (MOCID), Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (E.E.N.) 3 The Monitoring and Surveillance Center for Zoonotic Diseases in Wildlife and Exotic Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand; [email protected] 4 Department of Viral Infections, Research Institute for Microbial Diseases (RIMD), Osaka University, Osaka 565-0871, Japan 5 Department of Clinical Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.S.); [email protected] (P.L.) Citation: Poltep, K.; Phadungsombat, Abstract: Dengue is an arboviral disease highly endemic in Bangkok, Thailand. To characterize J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Kosoltanapiwat, the current genetic diversity of dengue virus (DENV), we recruited patients with suspected DENV N.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; infection at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Bangkok, during 2018–2020. We determined complete Wiriyarat, W.; Shioda, T.; nucleotide sequences of the DENV envelope region for 111 of 276 participant serum samples. -

Hantavirus Disease Were HPS Is More Common in Late Spring and Early Summer in Seropositive in One Study in the U.K

Hantavirus Importance Hantaviruses are a large group of viruses that circulate asymptomatically in Disease rodents, insectivores and bats, but sometimes cause illnesses in humans. Some of these agents can occur in laboratory rodents or pet rats. Clinical cases in humans vary in Hantavirus Fever, severity: some hantaviruses tend to cause mild disease, typically with complete recovery; others frequently cause serious illnesses with case fatality rates of 30% or Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal higher. Hantavirus infections in people are fairly common in parts of Asia, Europe and Syndrome (HFRS), Nephropathia South America, but they seem to be less frequent in North America. Hantaviruses may Epidemica (NE), Hantavirus occasionally infect animals other than their usual hosts; however, there is currently no Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), evidence that they cause any illnesses in these animals, with the possible exception of Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary nonhuman primates. Syndrome, Hemorrhagic Nephrosonephritis, Epidemic Etiology Hemorrhagic Fever, Korean Hantaviruses are members of the genus Orthohantavirus in the family Hantaviridae Hemorrhagic Fever and order Bunyavirales. As of 2017, 41 species of hantaviruses had officially accepted names, but there is ongoing debate about which viruses should be considered discrete species, and additional viruses have been discovered but not yet classified. Different Last Updated: September 2018 viruses tend to be associated with the two major clinical syndromes in humans, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary (or cardiopulmonary) syndrome (HPS). However, this distinction is not absolute: viruses that are usually associated with HFRS have been infrequently linked to HPS and vice versa. A mild form of HFRS in Europe is commonly called nephropathia epidemica. -

Taxonomy of the Order Bunyavirales: Update 2019

Archives of Virology (2019) 164:1949–1965 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-019-04253-6 VIROLOGY DIVISION NEWS Taxonomy of the order Bunyavirales: update 2019 Abulikemu Abudurexiti1 · Scott Adkins2 · Daniela Alioto3 · Sergey V. Alkhovsky4 · Tatjana Avšič‑Županc5 · Matthew J. Ballinger6 · Dennis A. Bente7 · Martin Beer8 · Éric Bergeron9 · Carol D. Blair10 · Thomas Briese11 · Michael J. Buchmeier12 · Felicity J. Burt13 · Charles H. Calisher10 · Chénchén Cháng14 · Rémi N. Charrel15 · Il Ryong Choi16 · J. Christopher S. Clegg17 · Juan Carlos de la Torre18 · Xavier de Lamballerie15 · Fēi Dèng19 · Francesco Di Serio20 · Michele Digiaro21 · Michael A. Drebot22 · Xiaˇoméi Duàn14 · Hideki Ebihara23 · Toufc Elbeaino21 · Koray Ergünay24 · Charles F. Fulhorst7 · Aura R. Garrison25 · George Fú Gāo26 · Jean‑Paul J. Gonzalez27 · Martin H. Groschup28 · Stephan Günther29 · Anne‑Lise Haenni30 · Roy A. Hall31 · Jussi Hepojoki32,33 · Roger Hewson34 · Zhìhóng Hú19 · Holly R. Hughes35 · Miranda Gilda Jonson36 · Sandra Junglen37,38 · Boris Klempa39 · Jonas Klingström40 · Chūn Kòu14 · Lies Laenen41,42 · Amy J. Lambert35 · Stanley A. Langevin43 · Dan Liu44 · Igor S. Lukashevich45 · Tāo Luò1 · Chuánwèi Lüˇ 19 · Piet Maes41 · William Marciel de Souza46 · Marco Marklewitz37,38 · Giovanni P. Martelli47 · Keita Matsuno48,49 · Nicole Mielke‑Ehret50 · Maria Minutolo3 · Ali Mirazimi51 · Abulimiti Moming14 · Hans‑Peter Mühlbach50 · Rayapati Naidu52 · Beatriz Navarro20 · Márcio Roberto Teixeira Nunes53 · Gustavo Palacios25 · Anna Papa54 · Alex Pauvolid‑Corrêa55 · Janusz T. Pawęska56,57 · Jié Qiáo19 · Sheli R. Radoshitzky25 · Renato O. Resende58 · Víctor Romanowski59 · Amadou Alpha Sall60 · Maria S. Salvato61 · Takahide Sasaya62 · Shū Shěn19 · Xiǎohóng Shí63 · Yukio Shirako64 · Peter Simmonds65 · Manuela Sironi66 · Jin‑Won Song67 · Jessica R. Spengler9 · Mark D. Stenglein68 · Zhèngyuán Sū19 · Sùróng Sūn14 · Shuāng Táng19 · Massimo Turina69 · Bó Wáng19 · Chéng Wáng1 · Huálín Wáng19 · Jūn Wáng19 · Tàiyún Wèi70 · Anna E. -

Yellow Head Virus: Transmission and Genome Analyses

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2008 Yellow Head Virus: Transmission and Genome Analyses Hongwei Ma University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biology Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Hongwei, "Yellow Head Virus: Transmission and Genome Analyses" (2008). Dissertations. 1149. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1149 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi YELLOW HEAD VIRUS: TRANSMISSION AND GENOME ANALYSES by Hongwei Ma Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2008 COPYRIGHT BY HONGWEI MA 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi YELLOW HEAD VIRUS: TRANSMISSION AND GENOME ANALYSES by Hongwei Ma A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: December 2008 ABSTRACT YELLOW HEAD VIRUS: TRANSMISSION AND GENOME ANALYSES by I Iongwei Ma December 2008 Yellow head virus (YHV) is an important pathogen to shrimp aquaculture. Among 13 species of naturally YHV-negative crustaceans in the Mississippi coastal area, the daggerblade grass shrimp, Palaemonetes pugio, and the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, were tested for potential reservoir and carrier hosts of YHV using PCR and real time PCR. -

Taxonomy of the Order Bunyavirales: Second Update 2018

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Arch Virol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2020 March 01. Published in final edited form as: Arch Virol. 2019 March ; 164(3): 927–941. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-04127-3. TAXONOMY OF THE ORDER BUNYAVIRALES: SECOND UPDATE 2018 A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the article. Abstract In October 2018, the order Bunyavirales was amended by inclusion of the family Arenaviridae, abolishment of three families, creation of three new families, 19 new genera, and 14 new species, and renaming of three genera and 22 species. This article presents the updated taxonomy of the order Bunyavirales as now accepted by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Keywords Arenaviridae; arenavirid; arenavirus; bunyavirad; Bunyavirales; bunyavirid; Bunyaviridae; bunyavirus; emaravirus; Feraviridae; feravirid, feravirus; fimovirid; Fimoviridae; fimovirus; goukovirus; hantavirid; Hantaviridae; hantavirus; hartmanivirus; herbevirus; ICTV; International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; jonvirid; Jonviridae; jonvirus; mammarenavirus; nairovirid; Nairoviridae; nairovirus; orthobunyavirus; orthoferavirus; orthohantavirus; orthojonvirus; orthonairovirus; orthophasmavirus; orthotospovirus; peribunyavirid; Peribunyaviridae; peribunyavirus; phasmavirid; phasivirus; Phasmaviridae; phasmavirus; phenuivirid; Phenuiviridae; phenuivirus; phlebovirus; reptarenavirus; tenuivirus; tospovirid; Tospoviridae; tospovirus; virus classification; virus nomenclature; virus taxonomy INTRODUCTION The virus order Bunyavirales was established in 2017 to accommodate related viruses with segmented, linear, single-stranded, negative-sense or ambisense RNA genomes classified into 9 families [2]. Here we present the changes that were proposed via an official ICTV taxonomic proposal (TaxoProp 2017.012M.A.v1.Bunyavirales_rev) at http:// www.ictvonline.org/ in 2017 and were accepted by the ICTV Executive Committee (EC) in [email protected]. -

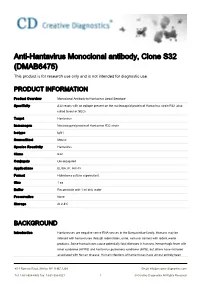

Anti-Hantavirus Monoclonal Antibody, Clone S32 (DMAB6475) This Product Is for Research Use Only and Is Not Intended for Diagnostic Use

Anti-Hantavirus Monoclonal antibody, Clone S32 (DMAB6475) This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic use. PRODUCT INFORMATION Product Overview Monoclonal Antibody to Hantavirus Seoul Serotype Specificity S32 reacts with an epitope present on the nucleocapsid protein of Hantavirus strain R22 (also called Seoul or SEO) Target Hantavirus Immunogen Nucleocapsid protein of Hantavirus R22 strain Isotype IgG1 Source/Host Mouse Species Reactivity Hantavirus Clone S32 Conjugate Unconjugated Applications ELISA, IF, IHC-Fr Format Hybridoma culture supernatant Size 1 ea Buffer Reconstitute with 1 ml dist. water Preservative None Storage At 2-8℃ BACKGROUND Introduction Hantaviruses are negative sense RNA viruses in the Bunyaviridae family. Humans may be infected with hantaviruses through rodent bites, urine, saliva or contact with rodent waste products. Some hantaviruses cause potentially fatal diseases in humans, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), but others have not been associated with human disease. Human infections of hantaviruses have almost entirely been 45-1 Ramsey Road, Shirley, NY 11967, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: 1-631-624-4882 Fax: 1-631-938-8221 1 © Creative Diagnostics All Rights Reserved linked to human contact with rodent excrement, but recent human-to-human transmission has been reported with the Andes virus in South America. The name hantavirus is derived from the Hantan River area in South Korea, which provided the founding member of the group: Hantaan virus (HTNV), isolated in the late 1970s by Ho-Wang Lee and colleagues. HTNV is one of several hantaviruses that cause HFRS, formerly known as Korean hemorrhagic fever. -

Virus Kit Description List

VIRUS –Complete list and description CONTENTS – italics names are the common names you might be more familiar with. ADENOVIRUS 46. Cytomegalovirus 98. Parapoxvirus 1. Atadenovirus 47. Muromegalovirus 99. Suipoxvirus 2. Aviadenovirus 48. Proboscivirus 100. Yatapoxvirus 3. Ichtadenovirus 49. Roseolovirus 101. Alphaentomopoxvirus 4. Mastadenovirus 50. Lymphocryptovirus 102. Betaentomopoxvirus 5. Siadenovirus 51. Rhadinovirus 103. Gammaentomopoxvirus ANELLOVIRUS 52. Misc. herpes REOVIRUS 6. Alphatorquevirus IFLAVIRUS 104. Cardoreovirus 7. Betatorquevirus 53. Iflavirus 105. Mimoreovirus 8. Gammatorquevirus ORTHOMYXOVIRUS 106. Orbivirus 9. Deltatorquevirus 54. Influenzavirus A 107. Phytoreovirus 10. Epsilontorquevirus 55. Influenzavirus B 108. Rotavirus 11. Etatorquevirus 56. Influenzavirus C 109. Seadornavirus 12. Iotatorquevirus 57. Isavirus 110. Aquareovirus 13. Thetatorquevirus 58. Thogotovirus 111. Coltivirus 14. Zetatorquevirus PAPILLOMAVIRUS 112. Cypovirus ARTERIVIRUS 59. Papillomavirus 113. Dinovernavirus 15. Equine arteritis virus PARAMYXOVIRUS 114. Fijivirus ARENAVIRUS 60. Avulavirus 115. Idnoreovirus 16. Arena virus 61. Henipavirus 116. Mycoreovirus ASFIVIRUS 62. Morbillivirus 117. Orthoreovirus 17. African swine fever virus 63. Respirovirus 118. Oryzavirus ASTROVIRUS 64. Rubellavirus RETROVIRUS 18. Mamastrovirus 65. TPMV~virus 119. Alpharetrovirus 19. Avastrovirus 66. Pneumovirus 120. Betaretrovirus BORNAVIRUS 67. Metapneumovirus 121. Deltaretrovirus 20. Borna virus 68. Para. Unassigned 122. Epsilonretrovirus BUNYAVIRUS PARVOVIRUS -

Current Developments and Challenges in Plant Viral Diagnostics: a Systematic Review

viruses Review Current Developments and Challenges in Plant Viral Diagnostics: A Systematic Review Gajanan T. Mehetre 1, Vincent Vineeth Leo 1 , Garima Singh 2 , Antonina Sorokan 3, Igor Maksimov 3, Mukesh Kumar Yadav 4, Kalidas Upadhyaya 5,*, Abeer Hashem 6,7, Asma N. Alsaleh 6 , Turki M. Dawoud 6, Khalid S. Almaary 6 and Bhim Pratap Singh 8,* 1 Department of Biotechnology, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram 796004, India; [email protected] (G.T.M.); [email protected] (V.V.L.) 2 Department of Botany, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 796001, India; [email protected] 3 Institute of Biochemistry and Genetics, Ufa Federal Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, pr. Oktyabrya 71, 450054 Ufa, Russia; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (I.M.) 4 Department of Biotechnology, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 796001, India; [email protected] 5 Department of Forestry, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram 796004, India 6 Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box. 2460, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (A.N.A.); [email protected] (T.M.D.); [email protected] (K.S.A.) 7 Mycology and Plant Disease Survey Department, Plant Pathology Research Institute, ARC, Giza 12511, Egypt 8 Department of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship & Management (NIFTEM), Industrial Estate, Kundli 131028, India * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.U.); [email protected] (B.P.S.); Tel.: +91-9436374242 (K.U.); Citation: Mehetre, G.T.; Leo, V.V.; +91-9436353807 (B.P.S.) Singh, G.; Sorokan, A.; Maksimov, I.; Yadav, M.K.; Upadhyaya, K.; Hashem, Abstract: Plant viral diseases are the foremost threat to sustainable agriculture, leading to several A.; Alsaleh, A.N.; Dawoud, T.M.; et al. -

Mouse Anti-HFRS Virus, Hanta Strain Monoclonal Antibody

SPECIFICATION SHEET Rev 110621MAB-S0006 Mouse Anti-HFRS Virus, Hanta strain Monoclonal Antibody Mouse, Monoclonal (HFRS Virus, Hanta strain) Cat. No. DMAB3487 Lot. No. (See product label) PRODUCT INFORMATION BACKGROUND Introduction: Hantaviruses (family Bunyaviridae, genus Han- Product Overview: Monoclonal Antibody to Hemorrhagic tavirus) are rodent-borne, zoonotic (acquired from animals), fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) Virus, Hanta Strain enveloped RNA viruses, and include the causative agents of Specificity: Specific for HFRS Virus. Strain: Hanta haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). The viruses Immunogen: Inactivated virus particles that cause HFRS include Hanta, Dobrava, Seoul, and Puu- Clone: C963M mala. Dobrova and Hanta viruses cause a more severe HFRS Isotype: IgG1 with fever, haemorrhage, and renal failure, and a mortality rate Host animal: Mouse. Hybridization of Sp2/0 myeloma cells of up to 15%. The mildest form of HFRS is caused by Puu- with spleen cells from BALB/c mice. mala virus. Source: Ascites Keywords: Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome Virus; Format: Purified, Liquid HFRS virus, Hanta strain; HFRS virus; Hemorrhagic fever with Applications: Suitable for use in ELISA. Each laboratory renal syndrome Virus, Hanta strain; Hantaviruses; Bunyaviri- should determine an optimum working titer for use in its par- dae; Hantavirus; Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome Vi- ticular application. Other applications have not been tested rus; HFRS Virus Dobrava, Puumala, Hanta and Seoul Strains; but use in such assays -

Infectious Diseases of Thailand

INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF THAILAND Stephen Berger, MD 2015 Edition Infectious Diseases of Thailand - 2015 edition Copyright Infectious Diseases of Thailand - 2015 edition Stephen Berger, MD Copyright © 2015 by GIDEON Informatics, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by GIDEON Informatics, Inc, Los Angeles, California, USA. www.gideononline.com Cover design by GIDEON Informatics, Inc No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. Contact GIDEON Informatics at [email protected]. ISBN: 978-1-4988-0637-4 Visit http://www.gideononline.com/ebooks/ for the up to date list of GIDEON ebooks. DISCLAIMER Publisher assumes no liability to patients with respect to the actions of physicians, health care facilities and other users, and is not responsible for any injury, death or damage resulting from the use, misuse or interpretation of information obtained through this book. Therapeutic options listed are limited to published studies and reviews. Therapy should not be undertaken without a thorough assessment of the indications, contraindications and side effects of any prospective drug or intervention. Furthermore, the data for the book are largely derived from incidence and prevalence statistics whose accuracy will vary widely for individual diseases and countries. Changes in endemicity, incidence, and drugs of choice may occur. The list of drugs, infectious diseases and even country names will vary with time. Scope of Content Disease designations may reflect a specific pathogen (ie, Adenovirus infection), generic pathology (Pneumonia - bacterial) or etiologic grouping (Coltiviruses - Old world). Such classification reflects the clinical approach to disease allocation in the Infectious Diseases Module of the GIDEON web application. -

Taxonomy of the Order Bunyavirales: Second Update 2018

TAXONOMY OF THE ORDER BUNYAVIRALES: SECOND UPDATE 2018 Piet Maes1,$,@, Scott Adkins2,$,&,⁜, Sergey V. Alkhovsky (Альховский Сергей Владимирович)3,^,&, Tatjana Avšič-Županc4,^, Matthew J. Ballinger5,⁜, Dennis A. Bente6,^, Martin Beer7,&, Éric Bergeron8,^, Carol D. Blair9,&, Thomas Briese10,⁂ , Michael J. Buchmeier11,%, Felicity J. Burt12,^, Charles H. Calisher9,@,&, Rémi N. Charrel14,%,$,⁂ , Il Ryong Choi15,⁑, J. Christopher S. Clegg16,%, Juan Carlos de la Torre17,%,$,, Xavier de Lamballerie14,⁂ , Joseph L. DeRisi18, Michele Digiaro19,#, Mike Drebot20,^, Hideki Ebihara ( 海老原秀喜)21,⁂ , Toufic Elbeaino19,#, Koray Ergünay22,^, Charles F. Fulhorst6,@, Aura R. Garrison23,^, George Fú Gāo (高福)24,⁂ , Jean-Paul J. Gonzalez25,%, Martin H. Groschup26,⁂ , Stephan Günther27%, Anne-Lise Haenni28,⁑, Roy A. Hall29,⁜, Roger Hewson30,^, Holly R. Hughes31,^, Rakesh K. Jain32, Miranda Gilda Jonson33⁑, Sandra Junglen34,35,$,⁜, Boris Klempa34,36,@, Jonas Klingström37,@, Richard Kormelink38, Amy J. Lambert31,$,&,⁜, Stanley A. Langevin39,⁜, Igor S. Lukashevich40,%, Marco Marklewitz35,36,&, Giovanni P. Martelli41,#, Nicole Mielke-Ehret42,#, Ali Mirazimi43,^, Hans-Peter Mühlbach42,#, Rayapati Naidu44,⁜, Márcio Roberto Teixeira Nunes45,&,⁂ , Gustavo Palacios25,$,^,⁂ , Anna Papa (Άννα Παπά)46,^, Janusz T. Pawęska47,48,^, Clarence J. Peters6, Alexander Plyusnin49, Sheli R. Radoshitzky23,%, Renato O. Resende50,⁜, Víctor Romanowski51,%, Amadou Alpha Sall52,^, Maria S. Salvato53,%, Takahide Sasaya (笹谷孝英)54,$,⁑,⁂ , Connie Schmaljohn25, Xiǎohóng Shí (石晓宏) 55,&, Yukio Shirako56,⁑, -

Geographical Distribution and Relative Risk of Anjozorobe Virus (Thailand

Raharinosy et al. Virology Journal (2018) 15:83 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-018-0992-9 RESEARCH Open Access Geographical distribution and relative risk of Anjozorobe virus (Thailand orthohantavirus) infection in black rats (Rattus rattus) in Madagascar Vololoniaina Raharinosy1,2, Marie-Marie Olive1, Fehivola Mandanirina Andriamiarimanana3, Soa Fy Andriamandimby1, Jean-Pierre Ravalohery1, Seta Andriamamonjy1, Claudia Filippone1, Danielle Aurore Doll Rakoto4, Sandra Telfer5† and Jean-Michel Heraud1*† Abstract Background: Hantavirus infection is a zoonotic disease that is associated with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and cardiopulmonary syndrome in human. Anjozorobe virus, a representative virus of Thailand orthohantavirus (THAIV), was recently discovered from rodents in Anjozorobe-Angavo forest in Madagascar. To assess the circulation of hantavirus at the national level, we carried out a survey of small terrestrial mammals from representative regions of the island and identified environmental factors associated with hantavirus infection. As we were ultimately interested in the potential for human exposure, we focused our research in the peridomestic area. Methods: Sampling was achieved in twenty districts of Madagascar, with a rural and urban zone in each district. Animals were trapped from a range of habitats and examined for hantavirus RNA by nested RT-PCR. We also investigated the relationship between hantavirus infection probability in rats and possible risk factors by using Generalized Linear Mixed Models. Results: Overall, 1242 specimens from seven species were collected (Rattus rattus, Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus, Suncus murinus, Setifer setosus, Tenrec ecaudatus, Hemicentetes semispinosus). Overall, 12.4% (111/897) of Rattus rattus and 1.6% (2/125) of Mus musculus were tested positive for THAIV.