From Frontline to Homefront the Global Homeland in Contemporary U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y Ear)

6/26/2019 American Lit Summer Reading 2019-20 - Google Docs 11 th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y ear) Welcome to American Literature! This summer assignment is meant to keep your reading and writing skills fresh. You should choose carefully —select books that will be interesting and enjoyable for you. Any assignments that do not follow directions exactly will not be accepted. This assignment is due Friday, August 16, 2019 to your American Literature Teacher. This will count as your first formative grade and be used as a diagnostic for your writing ability. Directions: For your summer assignment, please choose o ne of the following books to read. You can choose if your book is Fiction or Nonfiction. Fiction Choices Nonfiction Choices Catch 22 by Joseph Heller The satirical story of a WWII soldier who The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs. An account thinks everyone is trying to kill him and hatches plot after plot to keep of a young African‑American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend from having to fly planes again. Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison The story of an abusive “nuanced and shattering” ( People ) and “mesmeric” ( The New York Southern childhood. Times Book Review ) . The Known World by Edward P. Jones The story of a black, slave Outliers / Blink / The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating owning family. statistical studies of everyday phenomena. For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway A young American The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story by Richard Preston There is an anti‑fascist guerilla in the Spanish civil war falls in love with a complex outbreak of ebola virus in an American lab, and other stories of germs woman. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Award Winners

RITA Awards (Romance) Silent in the Grave / Deanna Ray- bourn (2008) Award Tribute / Nora Roberts (2009) The Lost Recipe for Happiness / Barbara O'Neal (2010) Winners Welcome to Harmony / Jodi Thomas (2011) How to Bake a Perfect Life / Barbara O'Neal (2012) The Haunting of Maddy Clare / Simone St. James (2013) Look for the Award Winner la- bel when browsing! Oshkosh Public Library 106 Washington Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54901 Phone: 920.236.5205 E-mail: Nothing listed here sound inter- [email protected] Here are some reading suggestions to esting? help you complete the “Award Winner” square on your Summer Reading Bingo Ask the Reference Staff for card! even more awards and winners! 2016 National Book Award (Literary) The Fifth Season / NK Jemisin Pulitzer Prize (Literary) Fiction (2016) Fiction The Echo Maker / Richard Powers (2006) Gilead / Marilynn Robinson (2005) Tree of Smoke / Dennis Johnson (2007) Agatha Awards (Mystery) March /Geraldine Brooks (2006) Shadow Country / Peter Matthiessen (2008) The Virgin of Small Plains /Nancy The Road /Cormac McCarthy (2007) Let the Great World Spin / Colum McCann Pickard (2006) The Brief and Wonderous Life of Os- (2009) A Fatal Grace /Louise Penny car Wao /Junot Diaz (2008) Lord of Misrule / Jaimy Gordon (2010) (2007) Olive Kitteridge / Elizabeth Strout Salvage the Bones / Jesmyn Ward (2011) The Cruelest Month /Louise Penny (2009) The Round House / Louise Erdrich (2012) (2008) Tinker / Paul Harding (2010) The Good Lord Bird / James McBride (2013) A Brutal Telling /Louise Penny A Visit -

American War Fiction from Vietnam to Iraq Elizabeth Eggert Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2018 Shifting Binaries: American War Fiction from Vietnam to Iraq Elizabeth Eggert Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Eggert, Elizabeth, "Shifting Binaries: American War Fiction from Vietnam to Iraq" (2018). English Honors Projects. 42. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/42 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shifting Binaries: American War Fiction from Vietnam to Iraq By Elizabeth Eggert Honors Thesis Presented to the Macalester College English Department Faculty Advisor: James Dawes April 5, 2018 Acknowledgements First and foremost, thank you to my advisor, Jim Dawes, for his support in the development, editing, and completion of this project. I would also like to thank Penelope Geng and Karin Aguilar-San Juan for the time they spent reading and commenting on this paper. Finally, I want to thank my family and friends for their support, encouragement, and listening during this lengthy process. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: The Boundaries of Empathy in The Things They Carried 11 Chapter Two: In the Lake of the Woods and Memory 22 Chapter Three: Solipsism and the Absent Enemy in The Yellow Birds 34 Chapter Four: Redeployment and the Limits of the War Novel 47 Conclusion 60 Eggert 1 Introduction Poet and Vietnam War veteran Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Missing in Action” is constructed around a binary of an ‘us’ versus a ‘them.’ The poem appears in Komunyakaa’s second full-length book of poetry, Dien Cai Dau1, which focused on his experiences serving in Vietnam. -

Walthall 1 Bill Walthall Professor J

Walthall 1 Bill Walthall Professor J. Donica LIT 515: 20th Century American Literature October 16, 2016 The Yellow Birds: A Classic Modern No experience of a literary work happens in a vacuum. As a reader, one is affected (and, in a sense, effected) by what has been read before. The writer is no different, taking his own history of reading and putting it into the context of his life experience to forge a new work. Wartime can become a crucible for such creation, as in modern American fiction from Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms though Slaughterhouse-Five by Vonnegut to O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. The combat experiences that help create the war novel can also destroy the character within it. John Bartle, from Kevin Powers’ Iraq War novel The Yellow Birds, suffers from an unnamed mental condition that brings to mind posttraumatic stress disorder--PTSD. His unit-mates Sterling and Murphy suffer through the same Iraqi spring and summer of 2004, but while they succumb to suicides (active and passive, respectively), Bartle reaches the novel’s end alive and on the road to emotional recovery. In a text that draws upon Powers’ own experiences in the U.S. Army in Iraq, the narrator Bartle can be seen as Powers’ surrogate in a kind of bildungs-roman à clef, something of a cross between a coming-of-age story and a memoir with only a shell of fictionalization around it. In a simple narrative reading of The Yellow Birds, Bartle’s descent into PTSD is chronicled, and his recovery is achieved by gaining geographical and temporal remove from the war; in a more nuanced reading of the novel, however, Powers’ metafictional use of nonlinear structure and present-tense insertions, along with his intertextual Walthall 2 allusions--to works from authors as varied as Melville, Vonnegut, and Shakespeare--make the literary experience one of not merely character recovery, but authorial healing as well. -

Fire and Forget This Interview Was Generously Shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group

Common Reading Program 2014 St. Cloud State University Teaching and Discussion Guide 2 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Table of Contents I. Book Summary 3 II. A Talk with Matt 4-8 III. Iraq and Afghanistan War Timeline 9 IV. Map of Afghanistan 10 V. Map of Iraq 11 VI. Glossary 12 VII. Book Discussion and Facilitation guide 13-14 VIII. Teaching about wars in Iraq and Afghanistan 15 IX. Related Activities 16 X. National Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 17 XI. Local Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 18 XII. Related Books 19 XIII. Documentaries 20 XIV. Feature Film Suggestions 21 3 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Book Summary The stories aren't pretty and they aren't for the faint of heart. They are gritty, haunting, shocking—and unforgettable. Television reports, movies, newspapers, and blogs about the recent wars have offered snapshots of the fighting there. But this anthology brings us a chorus of powerful storytellers—some of the first bards from our recent wars, emerging voices and new talents—telling the kind of panoramic truth that only fiction can offer. What makes these stories even more remarkable is that all of them are written by men and women whose lives were directly engaged in the wars—soldiers, Marines, and an army spouse. Featuring a forward by National Book Award-winner Colum McCann, this anthology spans every era of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from Baghdad to Brooklyn, from Kabul to Fort Hood. 4 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide A Talk with Matt Gallagher and Roy Scranton -Editors of Fire and Forget This interview was generously shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group. -

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Suffered by Private John Bartle in Kevin Powers' the Yellow Birds

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER SUFFERED BY PRIVATE JOHN BARTLE IN KEVIN POWERS' THE YELLOW BIRDS THESIS By: Faizal Yusuf Satriawan NIM 16320135 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2020 POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER SUFFERED BY PRIVATE JOHN BARTLE IN KEVIN POWERS' THE YELLOW BIRDS THESIS Presented to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S.) By: Faizal Yusuf Satriawan NIM 16320135 Advisor: Muzakki Afifuddin, M.Pd. NIP 19761011 201101 1005 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2020 ii STATEMENT OF RESEARCHER SHIP I state that the thesis entitled "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Suffered by Private John Bartle in Kevin Powers' The Yellow Birds" is my original work. I do not include any materials previously written or published by another person, except those ones that are cited as references and written in the bibliography. Hereby, if there is an objection or claim, I am the only person who is responsible for that. Malang, June 19th 2020 The Researcher Faizal Yusuf Satriawan. NIM 16320135 iii APPROVAL SHEET This is to certify that Faizal Yusuf Satriawan's thesis entitled Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Suffered by Private John Bartle in Kevin Powers' The Yellow Birds has been approved for thesis examination at the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang, as one of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S.). Malang, June 19th 2020 Approved by Advisor, Head of Department of English Literature, Muzakki Afifuddin, M.Pd. -

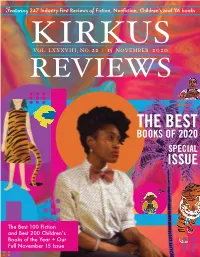

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

Education Page 14

Education Page 14 Monday and Tuesday lectures are in Orchestra Hall, and Wednesday and Thursday lectures are in Chautauqua Hall. The Chautauqua Prize Vearl Smith Historic 10:30 a.m., Monday: Redeployment: A Writer’s Journey with Phil Klay Preservation Workshop (Orchestra Hall) After World War I, Louis Simpson wrote: “To a foot-soldier, war is almost Supported by the Vearl Smith Memorial Endowment for Historic Preservation entirely physical. That is why some men, when they think about war, fall silent. 10:30 a.m., Wednesday: Discovering Ohio Architecture with Barbara Powers Language seems to falsify physical life and to betray those who have experi- (Chautauqua Hall) enced it absolutely—the dead.” Discover the richness and diversity of Ohio’s architecture. The sto- Yet, after every war, veterans have taken up the task of rendering the seem- ry of Ohio, from early settlement, through industrial expansion, to mod- ingly unimaginable into words. National Book Award-winning author and Iraq ern times, is reflected in its landmark buildings, urban centers, small towns War veteran Phil Klay will describe his experiences in the Marine Corps, and and the work of specific architects and builders. This program will dis- why he ultimately decided that writing about Iraq was a necessity. cuss broad architectural trends and characteristics of specific styles ex- Klay is a graduate of Dartmouth College and a amined within the context of 19th and 20th century Ohio. Understand- veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps. He served from ing and appreciating historic architecture is key to its preservation. Learn January 2007 to February 2008 in Iraq’s Anbar about the programs offered through the State Historic Preservation Office Province as a Public Affairs Officer. -

Memory and the Sensations of War in Vergil's Aeneid and Kevin Powers

ANKE WALTER, “What it felt like”: Memory and the Sensations of War in Vergil’s Aeneid and Kevin Powers’ The Yellow Birds, in: Annemarie Ambühl (ed.), Krieg der Sinne – Die Sinne im Krieg. Kriegsdarstellungen im Spannungsfeld zwischen antiker und moderner Kultur / War of the Senses – The Senses in War. Interactions and tensions between representations of war in classical and modern culture = thersites 4 (2016), 275-312. KEYWORDS war; senses; memory; Vergil; Aeneid; novel; Iraq; Kevin Powers; The Yellow Birds ABSTRACT (English) The Nisus and Euryalus episode in the ninth book of Vergil’s Aeneid and Kevin Powers’ 2012 novel The Yellow Birds on a soldier’s experiences in the year 2004 during the American War in Iraq are both constructed around a very similar story pattern of two friends who go to war together and are faced with bloodlust, cruelty, death, mutilation, and the duties of friendship, as well as the grief and silencing of a bereft mother. While the narrative and commemorative background of the two texts is very different – including the sense of an anchoring in tradition, the role of memory, even the existence of a coherent plotline itself – both the Augustan epic and the modern novel employ strikingly similar techniques and sensory imagery in their bid to convey the fundamental experience of warfare and of “what it felt like” as vividly as possible. ABSTRACT (German) Die Episode von Nisus und Euryalus im neunten Buch der Aeneis Vergils und Kevin Powers’ Roman The Yellow Birds (2012) über die Erfahrungen eines Soldaten im Jahr 2004 während des amerikanischen Krieges gegen den Irak sind um ein sehr ähnliches Handlungsschema herum konstruiert: Es geht um zwei Freunde, die zusammen in den Krieg ziehen und mit blutigem Morden, Grausamkeit, Tod, Verstümmelung und den Pflichten der Freundschaft konfrontiert werden, ebenso wie um die Trauer der Mutter, die zum Schweigen gebracht wird. -

Award Winning Books

More Man Booker winners: 1995: Sabbath’s Theater by Philip Roth Man Booker Prize 1990: Possession by A. S. Byatt 1994: A Frolic of His Own 1989: Remains of the Day by William Gaddis 2017: Lincoln in the Bardo by Kazuo Ishiguro 1993: The Shipping News by Annie Proulx by George Saunders 1985: The Bone People by Keri Hulme 1992: All the Pretty Horses 2016: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 1984: Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner by Cormac McCarthy 2015: A Brief History of Seven Killings 1982: Schindler’s List by Thomas Keneally 1991: Mating by Norman Rush by Marlon James 1981: Midnight’s Children 1990: Middle Passage by Charles Johnson 2014: The Narrow Road to the Deep by Salman Rushdie More National Book winners: North by Richard Flanagan 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2013: Luminaries by Eleanor Catton 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2012: Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2011: The Sense of an Ending National Book Award 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron by Julian Barnes 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2010: The Finkler Question 2016: Underground Railroad by Howard Jacobson by Colson Whitehead 2009: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2008: The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 2007: The Gathering by Anne Enright 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride National Book Critics 2006: The Inheritance of Loss 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich by Kiran Desai 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward Circle Award 2005: The Sea by John Banville 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2004: The Line of Beauty 2009: Let the Great World Spin 2016: LaRose by Louise Erdrich by Alan Hollinghurst by Colum McCann 2015: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 2003: Vernon God Little by D.B.C. -

TY HAWKINS Chair and Associate Professor / Department of English Irby Hall 317I, University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR 72034 501.450.3674 / [email protected]

TY HAWKINS Chair and Associate Professor / Department of English Irby Hall 317I, University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR 72034 501.450.3674 / [email protected] Education Ph.D. in English Saint Louis University (May 2010) St. Louis, MO Primary Areas: Twentieth-Century and Twenty-First-Century American Literature Secondary Areas: American Cultural Rhetoric, American War Literature, Writing Pedagogy Qualifying exams passed with “Great Distinction” Dissertation: “Combat’s Implacable Allure: Reading Vietnam amid the War on Terror” M.A. in English Saint Louis University (May 2005) St. Louis, MO Thesis: “Quidditas Under Erasure, Claritas Deferred, Opposites Reconciled: The Dedalean Aesthetic and the Joycean Subject” B.A. in English and Spanish Westminster College (May 2002) Fulton, MO Magna cum laude Thesis: “Long Day: A Novel” Positions Held Department Chair and Associate Professor of English, University of Central Arkansas, July 2019-present Associate Professor of English, Walsh University, Summer 2016-July 2019 Director of the Honors Program, Walsh University, July 2015-July 2019 Incoming Director of the Honors Program, Walsh University, November 2014-June 2015 Coordinator of the Composition Program, Walsh University, Spring 2012-November 2014 Assistant Professor of English, Walsh University, Fall 2011-Spring 2016 Adjunct Assistant Professor of English, University of Illinois at Springfield, Spring 2011 Instructor of English and Honors, Saint Louis University, Fall 2003-Summer 2011 Publications Monographs Just War Theory in an Age of Terror: An Introduction with Readings, with Andrew Kim (in progress and solicited for review by the University of Notre Dame Press) Cormac McCarthy’s Philosophy. American Literature Readings in the 21st Century ser. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.