Draft Aphaenogaster Genomes Expand Our View of Ant Genome Size Variation Across Climate Gradients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Myrmecochore Species Abundance

EFFECTS OF MYRMECOCHORE SPECIES ABUNDANCE, DIVERSITY, AND FRUITING PHENOLOGY ON APHAENOGASTER (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) NESTING AND FORAGING IN SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN RICH COVE FORESTS A Thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology. By Mary N. Schultz Director: Dr. James T. Costa, Western Carolina University Biology Department Committee Members: Dr. Beverly Collins, Western Carolina University Biology Department Dr. Robert Warren III, State University of New York College at Buffalo Biology Department April, 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members and director for their assistance and support, particularly logistical, conceptual, and editorial guidance from Dr. Beverly Collins; statistical and editorial assistance from Dr. Robert Warren; and keen proofreading and editorial comments from Dr. James T. Costa. I would also like to thank Dr. Mark Bradford, Yale school of Forestry and Environmental Studies, for funding my research. I am eternally grateful to my husband, David Clarke, for his continued unwavering support, in the field and out; none of this would have been possible without him. Lastly, my sincere appreciation for generous counsel and sage advice from my friends, Josh Kelly and Jay Kranyik. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................... -

The Ants of Oklahoma Master of Science

THE ANTS OF OKLAHOMA By Jerry H. Young(I\" Bachelor of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater, Oklahoma 1955 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE January 1 1956 tl<lAWMA AGCMCl«.f�Al L �Ci'!AlttCAl e&U.Ull LIBRARY JUL16195 6 THE ANTS OF OKLAHOMA Thesis Approved: Thesis Adviser }>JcMem��f � 't'" he Thesis ) Committee Member of the Thesis Committee 7'4'.��Member of the Thesis Committee Head of the Department ifean of the Graduate School 361565 ii PREFACE The study of the distribution of ants in the United States has been a long and continuous process with many contributors, but the State of Oklahoma has not received the attentions of these observers to any great extent. The only known list of ants of Oklahoma is one prepared by Mo Ro Smith (1935)0 Early in 1954 a survey of the state of Oklahoma was made to determine the species present and their distributiono The results of this survey, which blanketed the entire State, are given in this paper. The author wishes to express his appreciation to Dro Do E. Howell, chairman of the writer's thesis committee, for his valuable assistance and careful guidance in the preparation of this papero Also, much guidance on preparation of this manuscrip_t was received from Drs. Do Eo Bryan, William H. Irwin and F. A. Fenton. Many of the determin ations were made by M. R. Smith.. Vital infonnation was obtained from the museums at Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College and the University of Oklahoma. -

Native and Non-Native Ant Impacts on Native Fungi

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Biology Theses Biology 8-2021 Native and non-native ant impacts on native fungi Chloe Mokadam State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Robert J. Warren II, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Biology First Reader Christopher Pennuto, Ph.D., Professor of Biology Second Reader Olga Novikova, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Biology Department Chair Daniel L. Potts, Ph.D., Chair and Associate Professor of Biology To learn more about the Biology Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to https://biology.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Mokadam, Chloe, "Native and non-native ant impacts on native fungi" (2021). Biology Theses. 45. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/biology_theses/45 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/biology_theses Part of the Biology Commons Native and non-native ant impacts on native fungi by Chloe Mokadam An Abstract of a Thesis in Biology Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2021 Buffalo State College State University of New York Department of Biology 1 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Non-native ant impacts on native fungi Organisms produce weapons for defense against pathogens and competitors. In response, competitors and pathogens develop resistance to these weapons. However, when a species invades a new range, its “novel weapons” may be more effective against native species that did not co-evolve with them. Via specialized glands and microbial associates, ants produce antifungal weapons for defense against entomopathogenic fungi. -

Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

SYSTEMATICS Phylogenetic Analysis of Aphaenogaster Supports the Resurrection of Novomessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) 1 B. B. DEMARCO AND A. I. COGNATO Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, 288 Farm Lane, East Lansing, MI 48824. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 108(2): 201–210 (2015); DOI: 10.1093/aesa/sau013 ABSTRACT The ant genus Aphaenogaster Mayr is an ecologically diverse group that is common throughout much of North America. Aphaenogaster has a complicated taxonomic history due to variabil- ity of taxonomic characters. Novomessor Emery was previously synonymized with Aphaenogaster, which was justified by the partial mesonotal suture observed in Aphaenogaster ensifera Forel. Previous studies using Bayesian phylogenies with molecular data suggest Aphaenogaster is polyphyletic. Convergent evolution and retention of ancestral similarities are two major factors contributing to nonmonophyly of Aphaenogaster. Based on 42 multistate morphological characters and five genes, we found Novomessor more closely related to Veromessor Forel and that this clade is sister to Aphaenogaster. Our results confirm the validity of Novomessor stat. r. as a separate genus, and it is resurrected based on the combi- nation of new DNA, morphological, behavioral, and ecological data. KEY WORDS Aphaenogaster, Novomessor, phylogenetics, resurrection Introduction phylogenetic analyses resolved Aphaenogaster as polyphyletic, including Messor Forel, 1890 and Sten- The ant genus Aphaenogaster Mayr, 1853 is a speciose amma (Brady et al. 2006, Moreau and Bell 2013). group,whichhasnotbeentaxonomicallyreviewedin Ward (2011) suggested that convergent evolution and over 60 years (Creighton 1950). Aphaenogaster con- retention of ancestral similarities were two major fac- tains 227 worldwide species (Bolton 2006), with 23 tors contributing to polyphyly of Aphaenogaster. valid North American species reduced from 31 original Aphaenogaster taxonomy was further complicated species descriptions. -

Arkansas Academy of Science

Journal of the CODEN: AKASO ISBN: 0097-4374 ARKANSAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE VOLUME 61 2007 Library Rate ARKANSAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE ARKANSAS TECH UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL SCIENCES 1701 N. BOULDER RUSSELLVILLE. AR 72801-2222 Arkansas Academy ofScience, Dept. of Physical Sciences, Arkansas Tech University PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ARKANSAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE Charles Brookover, 1917 C. E. Hoffman, 1959 Paul Sharrah, 1984 Dwight M. Moore, 1932-33, 64 N. D. Buffaloe, 1960 William L. Evans, 1985 Flora Haas, 1934 H. L. Bogan, 1961 Gary Heidt, 1986 H. H. Hyman, 1935 Trumann McEver, 1962 Edmond Bacon, 1987 L. B. Ham, 1936 Robert Shideler, 1963 Gary Tucker, 1988 W. C. Muon, 1937 L. F. Bailey, 1965 David Chittenden, 1989 M. J. McHenry, 1938 James H. Fribourgh, 1966 Richard K. Speairs, Jr. 1990 T. L. Smith, 1939 Howard Moore, 1967 Robert Watson, 1991 P. G. Horton, 1940 John J. Chapman, 1968 Michael W. Rapp, 1992 I. A. Willis, 1941-42 Arthur Fry, 1969 Arthur A. Johnson, 1993 L. B. Roberts, 1943-44 M. L. Lawson, 1970 George Harp, 1994 JeffBanks, 1945 R. T. Kirkwood, 1971 James Peck, 1995 H. L. Winburn, 1946-47 George E. Templeton, 1972 Peggy R. Dorris, 1996 E. A. Provine, 1948 E. B. Wittlake, 1973 Richard Kluender, 1997 G. V. Robinette, 1949 Clark McCarty, 1974 James Daly, 1998 John R. Totter, 1950 Edward Dale, 1975 Rose McConnell, 1999 R. H. Austin, 1951 Joe Guenter, 1976 Mostafa Hemmati, 2000 E. A. Spessard, 1952 Jewel Moore, 1977 Mark Draganjac, 2001 Delbert Swartz, 1953 Joe Nix, 1978 John Rickett, 2002 Z. -

Nutritional Ecology of Aphaenogaster Ants in Response to Climate Change Katie A

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 Nutritional Ecology of Aphaenogaster Ants in Response to Climate Change Katie A. Miller University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Katie A., "Nutritional Ecology of Aphaenogaster Ants in Response to Climate Change" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 899. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/899 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NUTRITIONAL ECOLOGY OF APHAENOGASTER ANTS IN RESPONSE TO CLIMATE CHANGE A Thesis Presented by Katie Ann Miller to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Biology May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21st, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Sara Helms Cahan, Ph.D., Advisor Kimberly Wallin, Ph.D., Chairperson Nicholas Gotelli, Ph.D. Jason Stockwell, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT Climate change is predicted to impact organismal nutritional ecology. Increased temperatures can directly accelerate physiological rate processes, which in turn, impact nutritional requirements. Climate change can also impact organisms indirectly by altering the quality and quantity of nutritional resources, creating the potential for nutritional mismatch between what nutrients are available in the environment and what organisms require. -

Evolutionary Innovations in Ants to Thermally Stressful Environments Andrew D

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2017 Evolutionary Innovations In Ants To Thermally Stressful Environments Andrew D. Nguyen University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Evolution Commons, and the Physiology Commons Recommended Citation Nguyen, Andrew D., "Evolutionary Innovations In Ants To Thermally Stressful Environments" (2017). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 739. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/739 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTIONARY INNOVATIONS IN ANTS TO THERMALLY STRESSFUL ENVIRONMENTS A Dissertation Presented by Andrew D. Nguyen to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Specializing in Biology May, 2017 Defense Date: March 29, 2017 Dissertation Examination Committee: Sara Helms Cahan, Ph.D., Co-advisor Nicholas J. Gotelli, Ph.D., Co-advisor Jill Preston, Ph.D., Chairperson Brent Lockwood, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT Temperature is a fundamental environmental force shaping species abundance and distributions through its effects on biochemical reaction rates, metabolism, activity, and reproduction. In light of future climate shifts, mainly driven by temperature increases, how will organisms persist in warmer environments? One molecular mechanism that may play an important role in coping with heat stress is the heat shock response (HSR), which protects against molecular damage. -

Evaluating the Impacts of Climate Change on Ant Biodiversity in the Temperate Forest Communities of the Northeastern United States

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall November 2014 TURNING UP THE HEAT ON THE LITTLE THINGS THAT RUN THE WORLD: EVALUATING THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON ANT BIODIVERSITY IN THE TEMPERATE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES Israel Del Toro University of Massachusetts - Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Del Toro, Israel, "TURNING UP THE HEAT ON THE LITTLE THINGS THAT RUN THE WORLD: EVALUATING THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON ANT BIODIVERSITY IN THE TEMPERATE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://doi.org/10.7275/vk8p-ae52 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/176 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TURNING UP THE HEAT ON THE LITTLE THINGS THAT RUN THE WORLD: EVALUATING THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON ANT BIODIVERSITY IN THE TEMPERATE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented by ISRAEL DEL TORO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2014 Organismic and Evolutionary Biology © Copyright by Israel Del Toro 2014 All Rights Reserved TURNING UP THE HEAT ON THE LITTLE THINGS THAT RUN THE WORLD: EVALUATING THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON ANT BIODIVERSITY IN THE TEMPERATE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented by ISRAEL DEL TORO Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Aaron M. -

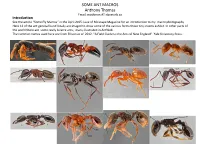

Some Ant Micros

SOME ANT MACROS Anthony Thomas Email: mothman AT nbnet.nb.ca Introduction See the article “Some Fly Macros” in the April 2015 issue of Micscape Magazine for an introduction to my macro photography. Here 12 of the ant genera found locally are imaged to show some of the various forms these tiny insects exhibit. In other parts of the world there are some really bizarre ants; many illustrated in AntWeb. The common names used here are from Ellison et al. 2012. “A Field Guide to the Ants of New England”. Yale University Press. The Ants Ants, of course, are Insects in the Order: Hymenoptera which includes the bees, wasps, and sawflies as well as the ants. The ants are placed in their own Family: Formicidae. The family is further subdivided into Subfamilies, Genera, and finally Species. In North America there are 10 Subfamilies, 73 Genera, and about 1,000 species. Where I live in New Brunswick, Canada, there are perhaps 15 genera and about 60 species. Within genera species identification is often difficult. However, it is relatively easy to place an ant into its correct genus. Most local ants are small, about 5mm or less for the workers and perhaps 13mm for the queens of some of the larger species. At 5mm the workers make interesting subjects for macro-photography; here I will show some of the different genera I have been able to find in the last couple of years. 1] Subfamily Ponerinae, The Wretched, Laboring Ants, Ponera These are regarded as primitive ants more closely related to the wasps than are the other subfamilies. -

Reprint Covers

TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM Speleological Monographs, Number 7 Studies on the CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA of North America Part V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher and James R. Reddell TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM SPELEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS, NUMBER 7 STUDIES ON THE CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA OF NORTH AMERICA, PART V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher Invertebrate Zoology, Natural Science Research Laboratory Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th Street Lubbock, Texas 79409 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] and James R. Reddell Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin, PRC 176, 10100 Burnet Austin, Texas 78758 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] March 2009 TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM and the TEXAS NATURAL SCIENCE CENTER THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 Copyright 2009 by the Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin All rights rereserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrival systems, except by explict, prior written permission of the publisher Printed in the United States of America Cover, The first troglobitic weevil in North America, Lymantes Illustration by Nadine Dupérré Layout and design by James C. Cokendolpher Printed by the Texas Natural Science Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas PREFACE This is the fifth volume in a series devoted to the cavernicole and endogean fauna of the Americas. Previous volumes have been limited to North and Central America. Most of the species described herein are from Texas and Mexico, but one new troglophilic spider is from Colorado (U.S.A.) and a remarkable new eyeless endogean scorpion is described from Colombia, South America. -

Effects of Forest Edges, Exotic Ants and Nonnative Plants on Local Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Diversity in Urban Forest Fragments of Northeastern Ohio

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2010 Effects of Forest Edges, Exotic Ants and Nonnative Plants on Local Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Diversity in Urban Forest Fragments of Northeastern Ohio Kaloyan Ivanov Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Ivanov, Kaloyan, "Effects of Forest Edges, Exotic Ants and Nonnative Plants on Local Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Diversity in Urban Forest Fragments of Northeastern Ohio" (2010). ETD Archive. 141. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/141 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF FOREST EDGES, EXOTIC ANTS AND NONNATIVE PLANTS ON LOCAL ANT (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) DIVERSITY IN URBAN FOREST FRAGMENTS OF NORTHEASTERN OHIO KALOYAN IVANOV Master of Science in Entomology Sofia University Sofia, Bulgaria 2000 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN REGULATORY BIOLOGY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2010 This dissertation has been approved for the Department of Biological, Geological, and Environmental Sciences and for the College of Graduate Studies by Date: Dr. Joe B. Keiper, Virginia Museum of Natural History Major Advisor Date: Dr. B. Michael Walton, BGES / CSU Advisory Committee Member Date: Dr. Robert A. Krebs, BGES / CSU Advisory Committee Member Date: Dr. Jaharul Haque, The Cleveland Clinic Advisory Committee Member Date: Dr. -

Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida December 1986 A North Florida Ant Fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Clifford Johnson University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Johnson, Clifford, "A North Florida Ant Fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (1986). Insecta Mundi. 512. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/512 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Vol. 1, no. 4, December 1986 INSECTA MUNDI 243 AlOOglIi-mF- (@-wt- t ~~ddse) Clifford Johnson Ikpammt of Zoology uni~rsityof Florida Gainesvflle, FL 32611 llnmDumON texma carolWis ad h ,ddam, a form originally considered as a subspecies of A. texana, as occurring in This paper updates and surmarizes the ant fauna of Florida. The earlier naPes of A. t. silvestrii and A. t. Alachua County, Florida, with two basic objectives. 'Ihe nana, also cited for Florida, are deleted. Creighton first objective is presentation of a current, -ted (1950) suggested scme taxa in Aphaenogaster were based check-list consistent with existing taxonomy and an on the descriptions of mini- specimens and may be insight on species groups where taxonanic charges are invalid. Noting this variability, Carroll was unable to likely in subsequent revisions. Ihe seccnd objective find satisfactory differences between specimens thought seeks to identify changes in the fauna since Van Pelt's to represent both A.