Durga Puja in Calcutta’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18Th and 19Th Centuries): Historical Perspective

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Session: 2008-09 Academic Supervisor Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History University of Dhaka This Thesis Submitted to the Department of History University of Dhaka for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) December, 2013 Declaration This is to certify that Murshida Bintey Rahman has written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ under my supervision. She has written the thesis for the M.Phil degree in History. I further affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History Dated: University of Dhaka 2 Declaration I do declare that, I have written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ for the M.Phil degree in History. I affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Dated: Session: 2008-09 Department of History University of Dhaka 3 Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Abstract Banians or merchants’ bankers were the first Bengali collaborators or cross cultural brokers for the foreign merchants from the seventeenth century until well into the mid-nineteenth century Bengal. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

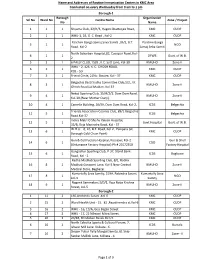

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

Shuktara October 2014 the Major Festival of Durga Puja Is Now Over

shuktara a new home in the world for young adults 43b/5 Narayan Roy Road P.S. Thakurpukur Kolkata 700008 West Bengal INDIA Contact no: - 91 33 2496 0051 October 2014 The major festival of Durga Puja is now over and by the time you read this, Diwali will also have come and gone. Diwali is celebrated in most of India, but here in West Bengal we celebrate Kali Puja. This is the night when Bengalis let off their fireworks, light candles and an evening that everyone at shuktara really enjoys. Because Diwali is usually the following day, they use this excuse and have two nights of fireworks! However this year, both festivals fall on the same day – but I expect they will keep some fireworks back anyway and celebrate for a couple of nights running. As with the Pujas, I usually hide away somewhere quietly! The Durga Puja festivities were enjoyed by everyone at shuktara. Some of the older boys went out on their own, some stayed at home and some of them went with Pappu to help carry Prity and our new girl Moni around the city. They always hire a big car for this occasion and stay out all night long. Sanjay Sarkar – Durga Puja 2014 Moni on 10th September 2014 Moni had come a short time before the Pujas and was very excited to have new clothes and jewellery to wear for her very first outing. At the beginning of September, Pappu had received a phone call from Childline India Foundation about a little girl who they were unable to care for. -

47 Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 Few Hindu Religious Festivals

“CHILDREN HAVE THEIR OWN WORLD OF BEING”: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES ON THE DAY OF SARASWATI PUJA SEMONTEE MITRA Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 few Hindu religious festivals are organized and celebrated publicly in the United States. Saraswati Puja is one such festival. Saraswati Puja, also known as Vasant Panchami, is a Hindu festival celebrated in early February to mark the onset of spring. On this day, Hindus, especially Bengalis,3 worship the goddess Saraswati, the Vedic goddess of knowledge and wisdom, music, arts, and science. She is also the companion of Lord Brahma who, with her knowledge and wisdom, created the universe. Bengalis consider participation in this puja4 compulsory for students, scholars, and creative artists. Therefore, Indian American Bengali parents force their children to participate in this festival, whereas they might be lax on other religious occasions. As a participant-observer of this recent Indian festival in Central Pennsylvania, United States, I found that the cultural scene—the collective, communal celebration of Saraswati Puja—was not as simple as children of foreign-born parents following a transplanted tradition and gaining ethnic identity. On the contrary, I noticed that Indian American Bengali children typically indulged in activities such as games that are not traditionally part of the religious observance in India. Their interactions, both in and out of the social frame of a religious ritual, especially Saraswati Puja, reveal that in America the festive day has taken on the function -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

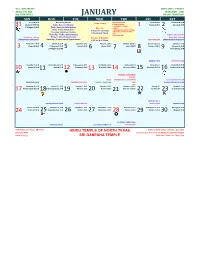

Temple Calendar

Year : SHAARVARI MARGASIRA - PUSHYA Ayana: UTTARA MARGAZHI - THAI Rtu: HEMANTHA JANUARY DHANU - MAKARAM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Tritiya 8.54 D Recurring Events Special Events Tritiya 9.40 N Chaturthi 8.52 N Temple Hours Chaturthi 6.55 ND Daily: Ganesha Homam 01 NEW YEAR DAY Pushya 8.45 D Aslesha 8.47 D 31 12 HANUMAN JAYANTHI 1 2 P Phalguni 1.48 D Daily: Ganesha Abhishekam Mon - Fri 13 BHOGI Daily: Shiva Abhishekam 14 MAKARA SANKRANTHI/PONGAL 9:30 am to 12:30 pm Tuesday: Hanuman Chalisa 14 MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm PUJA Thursday : Vishnu Sahasranama 28 THAI POOSAM VENKATESWARA PUJA Friday: Lalitha Sahasranama Moon Rise 9.14 pm Sat, Sun & Holidays Moon Rise 9.13 pm Saturday: Venkateswara Suprabhatam SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI 8:30 am to 8:30 pm NEW YEAR DAY SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI Panchami 7.44 N Shashti 6.17 N Saptami 4.34 D Ashtami 2.36 D Navami 12.28 D Dasami 10.10 D Ekadasi 7.47 D Magha 8.26 D P Phalguni 7.47 D Hasta 5.39 N Chitra 4.16 N Swati 2.42 N Vishaka 1.02 N Dwadasi 5.23 N 3 4 U Phalguni 6.50 ND 5 6 7 8 9 Anuradha 11.19 N EKADASI PUJA AYYAPPAN PUJA Trayodasi 3.02 N Chaturdasi 12.52 N Amavasya 11.00 N Prathama 9.31 N Dwitiya 8.35 N Tritiya 8.15 N Chaturthi 8.38 N 10 Jyeshta 9.39 N 11 Mula 8.07 N 12 P Ashada 6.51 N 13 U Ashada 5.58 D 14 Shravana 5.34 D 15 Dhanishta 5.47 D 16 Satabhisha 6.39 N MAKARA SANKRANTHI PONGAL BHOGI MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN SRINIVASA KALYANAM PRADOSHA PUJA HANUMAN JAYANTHI PUSHYA / MAKARAM PUJA SHUKLA CHATURTHI PUJA THAI Panchami 9.44 N Shashti 11.29 N Saptami 1.45 N Ashtami 4.20 N Navami 6.59 -

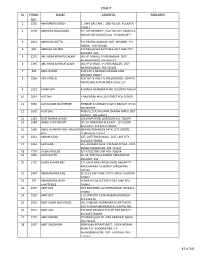

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

Schedule of DUARE SARKAR: Round-5 the KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION

Schedule of DUARE SARKAR: Round-5 THE KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Date Borough Ward Day Venue 27-01-2021 I 7 Wednesday Bagbazar Sarbajanin Durgotsab Math, 78 Baghbazar Street 28-01-2021 I 1 Thursday Uttarayan Community Hall, 1B, Gopal Chatterjee Road, kol - 02 29-01-2021 I 8 Friday A.V. School, 88 Shyambazar Street 02-02-2021 I 2 Tuesday Muktadhara Community Hall, 34 Harekrishna Sett Lane,Kol-50 03-02-2021 I 6 Wednesday Geetanjali community hall, 2 no. Lock Gate Road 05-02-2021 I 5 Friday Sonar Tori Community Hall, 7MG Tara Saankar Sarani 05-02-2021 I 9 Friday Pratistha Community Hall, 55 Jyotindra Mohan Avenue Manohar Academy School, Milk Colony, 64/77 Khidiram Bose Sarani, 06-02-2021 I 3 Saturday Duttabagan, kol - 37 08-02-2021 I 4 Monday Pubali Community Hall, Kheyali Park, Rani Harshamukhi Road 03-02-2021 II 15 Wednesday Pratyasa Community Hall, 82 Raja Dinendra Street, kol- 700006 03-02-2021 II 16 Wednesday GOA BAGAN WARD OFFICE 16 GOA BAGAN C.I.T PARK 04-02-2021 II 19 Thursday B. K. Pal Avenue Park, 105 B.K. Pal Avenue, Kol - 5 05-02-2021 II 10 Friday Laha Colony Math 05-02-2021 II 17 Friday Gana Bhawan, 22 Jatin Mohan Avenue, Sovabazar, Kol - 04 06-02-2021 II 18 Saturday Joy Mitra Park, 436 Rabindra Sarani, Kol-6 06-02-2021 II 20 Saturday Nahabat Community Hall 08-02-2021 II 11 Monday Star Community Hall, Khudiram Bose Lane, kol - 6 Monihar Community Hall, Raja Dinendra Street, near Deshbandhu Park, Kol- 08-02-2021 II 12 Monday 700006 28-01-2021 III 34 Thursday 27, Chaulpatti road, Kolkata- 10 29-01-2021 III 35 Friday Balir Math, 8 K G Bose Sarani, Kol - 85 01-02-2021 III 33 Monday Sarkar Math, 106 Beliaghata main road 03-02-2021 III 31 Wednesday Siksha Niketan School, 30E Ramkrishna Samadhi Road 04-02-2021 III 29 Thursday Community Hall, LIG Quarter, 19 No. -

BUS ROUTE-18-19 Updated Time.Xls LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS

LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT TO TO CONDITION OF THE ROAD CONDITION OF THE ROAD ROUTE NO - 1 ROUTE NO - 2 SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS 1 DUMDUM CENTRAL JAIL 13.00 1 IDEAL RESIDENCY 13.05 2 CLIVE HOUSE, MALL ROAD 13.03 2 KANKURGACHI MORE 13.07 3 KAJI PARA 13.05 3 MANICKTALA RAIL BRIDGE 13.08 4 MOTI JEEL 13.07 4 BAGMARI BAZAR 13.10 5 PRIVATE ROAD 13.09 5 MANICKTALA P.S. 13.12 6 CHATAKAL DUMDUM ROAD 13.11 6 MANICKTALA DINENDRA STREET XING 13.14 7 HANUMAN MANDIR 13.13 7 MANICKTALA BLOOD BANK 13.15 8 DUMDUM PHARI 01:15 8 GIRISH PARK METRO STATION 13.20 9 DUMDUM STATION 01:17 9 SOVABAZAR METRO STATION 13.23 10 7 TANK, DUMDUM RD 01:20 10 B.K.PAUL AVENUE 13.25 11 AHIRITALA SITALA MANDIR 13.27 12 JORABAGAN PARK 13.28 13 MALAPARA 13.30 14 GANESH TALKIES 13.32 15 RAM MANDIR 13.34 16 MAHAJATI SADAN 13.37 17 CENTRAL AVENUE RABINDRA BHARATI 13.38 18 M.G.ROAD - C.R.AVENUE XING 13.40 19 MOHD.ALI PARK 13.42 20 MEDICAL COLLEGE 13.44 21 BOWBAZAR XING 13.46 22 INDIAN AIRLINES 13.48 23 HIND CINEMA XING 13.50 24 LEE MEMORIAL SCHOOL - LENIN SR. 13.51 ROUTE NO - 3 ROUTE NO - 04 SL NO.