Overview 1. Gravitational Forces and Potentials (BT 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compton Scattering from the Deuteron at Low Energies

SE0200264 LUNFD6-NFFR-1018 Compton Scattering from the Deuteron at Low Energies Magnus Lundin Department of Physics Lund University 2002 W' •sii" Compton spridning från deuteronen vid låga energier (populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning på svenska) Vid Compton spridning sprids fotonen elastiskt, dvs. utan att förlora energi, mot en annan partikel eller kärna. Kärnorna som användes i detta försök består av en proton och en neutron (sk. deuterium, eller tungt väte). Kärnorna bestrålades med fotoner av kända energier och de spridda fo- tonerna detekterades mha. stora Nal-detektorer som var placerade i olika vinklar runt strålmålet. Försöket utfördes under 8 veckor och genom att räkna antalet fotoner som kärnorna bestålades med och antalet spridda fo- toner i de olika detektorerna, kan sannolikheten för att en foton skall spridas bestämmas. Denna sannolikhet jämfördes med en teoretisk modell som beskriver sannolikheten för att en foton skall spridas elastiskt mot en deuterium- kärna. Eftersom protonen och neutronen består av kvarkar, vilka har en elektrisk laddning, kommer dessa att sträckas ut då de utsätts för ett elek- triskt fält (fotonen), dvs. de polariseras. Värdet (sannolikheten) som den teoretiska modellen ger, beror på polariserbarheten hos protonen och neu- tronen i deuterium. Genom att beräkna sannolikheten för fotonspridning för olika värden av polariserbarheterna, kan man se vilket värde som ger bäst överensstämmelse mellan modellen och experimentella data. Det är speciellt neutronens polariserbarhet som är av intresse, och denna kunde bestämmas i detta arbete. Organization Document name LUND UNIVERSITY DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Department of Physics Date of issue 2002.04.29 Division of Nuclear Physics Box 118 Sponsoring organization SE-22100 Lund Sweden Author (s) Magnus Lundin Title and subtitle Compton Scattering from the Deuteron at Low Energies Abstract A series of three Compton scattering experiments on deuterium have been performed at the high-resolution tagged-photon facility MAX-lab located in Lund, Sweden. -

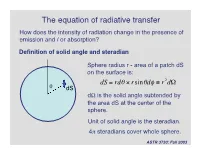

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Slides for Statistics, Precision, and Solid Angle

Slides for Statistics, Precision, and Solid Angle 22.01 – Intro to Radiation October 14, 2015 22.01 – Intro to Ionizing Radiation Precision etc., Slide 1 Solid Angles, Dose vs. Distance • Dose decreases with the inverse square of distance from the source: 1 퐷표푠푒 ∝ 푟2 • This is due to the decrease in solid angle subtended by the detector, shielding, person, etc. absorbing the radiation 22.01 – Intro to Ionizing Radiation Precision etc., Slide 2 Solid Angles, Dose vs. Distance • The solid angle is defined in steradians, and given the symbol Ω. • For a rectangle with width w and length l, at a distance r from a point source: 푤푙 Ω = 4푎푟푐푡푎푛 2푟 4푟2 + w2 + 푙2 • A full sphere has 4π steradians (Sr) 22.01 – Intro to Ionizing Radiation Precision etc., Slide 3 Solid Angles, Dose vs. Distance http://www.powerfromthesun.net/Book/chapter02/chapter02.html • Total luminance (activity) of a source is constant, but the flux through a surface decreases with distance Courtesy of William B. Stine. Used with permission. 22.01 – Intro to Ionizing Radiation Precision etc., Slide 4 Exponential Gamma Attenuation • Gamma sources are attenuated exponentially according to this formula: Initial intensity Mass attenuation coefficient 흁 Distance through − 흆 흆풙 푰 = 푰ퟎ풆 material Transmitted intensity Material density • Attenuation means removal from a narrowly collimated beam by any means 22.01 – Intro to Ionizing Radiation Precision etc., Slide 5 Exponential Gamma Attenuation Look up values in NIST x-ray attenuation tables: http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xraycoef/ Initial -

General Method of Solid Angle Calculation Using Attitude Kinematics

1 1 General method of solid angle calculation using attitude kinematics 2 3 Russell P. Patera1 4 351 Meredith Way, Titusville, FL 32780, United States 5 6 Abstract 7 A general method to compute solid angle is developed that is based on Ishlinskii’s theorem, which specifies the 8 relationship between the attitude transformation of an axis that completely slews about a conical region and the 9 solid angle of the enclosed region. After an axis slews about a conical region and returns to its initial orientation, it 10 will have rotated by an angle precisely equal to the enclosed solid angle. The rotation is the magnitude of the 11 Euler rotation vector of the attitude transformation produced by the slewing motion. Therefore, the solid angle 12 can be computed by first computing the attitude transformation of an axis that slews about the solid angle region 13 and then computing the solid angle from the attitude transformation. This general method to compute the solid 14 angle involves approximating the solid angle region’s perimeter as seen from the source, with a discrete set of 15 points on the unit sphere, which join a set of great circle arcs that approximate the perimeter of the region. Pivot 16 Parameter methodology uses the defining set of points to compute the attitude transformation of the axis due to 17 its slewing motion about the enclosed solid angle region. The solid angle is the magnitude of the resulting Euler 18 rotation vector representing the transformation. The method was demonstrated by comparing results to 19 published results involving the solid angles of a circular disk radiation detector with respect to point, line and disk 20 shaped radiation sources. -

From the Geometry of Foucault Pendulum to the Topology of Planetary Waves

From the geometry of Foucault pendulum to the topology of planetary waves Pierre Delplace and Antoine Venaille Univ Lyon, Ens de Lyon, Univ Claude Bernard, CNRS, Laboratoire de Physique, F-69342 Lyon, France Abstract The physics of topological insulators makes it possible to understand and predict the existence of unidirectional waves trapped along an edge or an interface. In this review, we describe how these ideas can be adapted to geophysical and astrophysical waves. We deal in particular with the case of planetary equatorial waves, which highlights the key interplay between rotation and sphericity of the planet, to explain the emergence of waves which propagate their energy only towards the East. These minimal in- gredients are precisely those put forward in the geometric interpretation of the Foucault pendulum. We discuss this classic example of mechanics to introduce the concepts of holonomy and vector bundle which we then use to calculate the topological properties of equatorial shallow water waves. Résumé La physique des isolants topologiques permet de comprendre et prédire l’existence d’ondes unidirectionnelles piégées le long d’un bord ou d’une interface. Nous décrivons dans cette revue comment ces idées peuvent être adaptées aux ondes géophysiques et astrophysiques. Nous traitons en parti- culier le cas des ondes équatoriales planétaires, qui met en lumière les rôles clés combinés de la rotation et de la sphéricité de la planète pour expliquer l’émergence d’ondes qui ne propagent leur énergie que vers l’est. Ces ingré- dients minimaux sont précisément ceux mis en avant dans l’interprétation géométrique du pendule de Foucault. -

Radiometry and Photometry

Radiometry and Photometry Wei-Chih Wang Department of Power Mechanical Engineering National TsingHua University W. Wang Materials Covered • Radiometry - Radiant Flux - Radiant Intensity - Irradiance - Radiance • Photometry - luminous Flux - luminous Intensity - Illuminance - luminance Conversion from radiometric and photometric W. Wang Radiometry Radiometry is the detection and measurement of light waves in the optical portion of the electromagnetic spectrum which is further divided into ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Example of a typical radiometer 3 W. Wang Photometry All light measurement is considered radiometry with photometry being a special subset of radiometry weighted for a typical human eye response. Example of a typical photometer 4 W. Wang Human Eyes Figure shows a schematic illustration of the human eye (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1994). The inside of the eyeball is clad by the retina, which is the light-sensitive part of the eye. The illustration also shows the fovea, a cone-rich central region of the retina which affords the high acuteness of central vision. Figure also shows the cell structure of the retina including the light-sensitive rod cells and cone cells. Also shown are the ganglion cells and nerve fibers that transmit the visual information to the brain. Rod cells are more abundant and more light sensitive than cone cells. Rods are 5 sensitive over the entire visible spectrum. W. Wang There are three types of cone cells, namely cone cells sensitive in the red, green, and blue spectral range. The approximate spectral sensitivity functions of the rods and three types or cones are shown in the figure above 6 W. Wang Eye sensitivity function The conversion between radiometric and photometric units is provided by the luminous efficiency function or eye sensitivity function, V(λ). -

Invariance Properties of the Dirac Monopole

fcs.- 0; /A }Ю-ц-^. KFKI-75-82 A. FRENKEL P. HRASKÓ INVARIANCE PROPERTIES OF THE DIRAC MONOPOLE Hungarian academy of Sciences CENTRAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR PHYSICS BUDAPEST L KFKI-75-S2 INVARIÄHCE PROPERTIES OF THE DIRAC MONOPOLE A. Frenkel and P. Hraskó High Energy Physics Department Central Research Institute for Physics, Budapest, Hungary ISBN 963 371 094 4 ABSTRACT The quantum mechanical motion of a spinless electron in the external field of a magnetic monopolé of magnetic charge v is investigated. Xt is shown that Dirac's quantum condition 2 ue(hc)'1 • n for the string being unobservable ensures rotation invarlance and correct space reflection proper ties for any integer value of n. /he rotation and space reflection operators are found and their group theoretical properties are discussed, A method for constructing conserved quantities In the case when the potential ie not explicitly invariant under the symmetry operation is also presented and applied to the discussion of the angular momentum of the electron-monopole system. АННОТАЦИЯ Рассматривается кваитоаомеханическое движение бесспинового элект рона во внешнем поле монополя с Магнитки« зарядом и. Доказывается» что кван товое условие Дирака 2ув(пс)-1 •> п обеспечивает не только немаолтваемость стру ны »но и инвариантность при вращении и правильные свойства при пространственных отражениях для любого целого п. Даются операторы времени* я отражения, и об суждаются их групповые свойства. Указан также метод построения интегралов движения в случае, когда потенциал не является язно инвариантным по отношению операции симметрии, и этот метод применяется при изучении углового момента сис темы электрон-монопопь. KIVONAT A spin nélküli elektron kvantummechanikai viselkedését vizsgáljuk u mágneses töltésű monopolus kttlsö terében. -

International System of Units (Si)

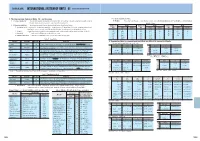

[TECHNICAL DATA] INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM OF UNITS( SI) Excerpts from JIS Z 8203( 1985) 1. The International System of Units( SI) and its usage 1-3. Integer exponents of SI units 1-1. Scope of application This standard specifies the International System of Units( SI) and how to use units under the SI system, as well as (1) Prefixes The multiples, prefix names, and prefix symbols that compose the integer exponents of 10 for SI units are shown in Table 4. the units which are or may be used in conjunction with SI system units. Table 4. Prefixes 1 2. Terms and definitions The terminology used in this standard and the definitions thereof are as follows. - Multiple of Prefix Multiple of Prefix Multiple of Prefix (1) International System of Units( SI) A consistent system of units adopted and recommended by the International Committee on Weights and Measures. It contains base units and supplementary units, units unit Name Symbol unit Name Symbol unit Name Symbol derived from them, and their integer exponents to the 10th power. SI is the abbreviation of System International d'Unites( International System of Units). 1018 Exa E 102 Hecto h 10−9 Nano n (2) SI units A general term used to describe base units, supplementary units, and derived units under the International System of Units( SI). 1015 Peta P 10 Deca da 10−12 Pico p (3) Base units The units shown in Table 1 are considered the base units. 1012 Tera T 10−1 Deci d 10−15 Femto f (4) Supplementary units The units shown in Table 2 below are considered the supplementary units. -

The International System of Units

Chapter 4 The International System of Units The International System (SI) is a units system created in 1960 in the 11th. General Conference on Weights and Measures [3]. Its purpose was to establish a standard unit system that would be adopted by all countries such that science could become truly universal. An experiment performed in any country could be easily reproduced in any other country. 4.1 The SI base units The International System was built from 7 base units [4]: Physical quantity SI unit Name Symbol Name Symbol length l, x, y, z, r,... meter m mass m, M kilogram kg time, duration t, ∆t second s electric current intensity I,i ampere A temperature T kelvin K luminous intensity IV candela cd quantity n mole mol Table 4.1: Base SI units 4.2 The SI derived units All physical quantities have units which are either one base unit or a combination of base units. If a unit results from combining more than one base unit it is call a derived unit. Some examples: . m2 - the “square meter” is the SI unit of area. It is considered a derived unit because it results from combining the same base unit more than once. Hz - the “hertz” is the SI unit of frequency. It also derives from a single SI unit and is considered derived because it is not equal to the base unit. This unit pays homage to Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (1857 1894). − 1 Hz = (4.1) s . N - the “newton” is the SI unit of force. It is derived from 3 SI base units: kg m N = · (4.2) s2 It pays homage to Sir Isaac Newton (1642 1727). -

Appendix a Plane and Solid Angles

Appendix A Plane and Solid Angles 1.0 A.1 Plane Angles y = tan θ y = sin θ The angle θ between two intersecting lines is shown in 0.8 y = θ (radians) Fig. A.1. It is measured by drawing a circle centered on the vertex or point of intersection. The arc length s on that part of the circle contained between the lines measures the angle. 0.6 In daily work, the angle is marked off in degrees. y In some cases, there are advantages to measuring the an- 0.4 gle in radians. This is particularly true when trigonometric functions have to be differentiated or integrated. The angle in radians is defined by 0.2 s θ = . (A.1) r 0.0 0 20 40 60 80 Since the circumference of a circle is 2πr, the angle corre- θ sponding to a complete rotation of 360 ◦ is 2πr/r = 2π. (degrees) Other equivalences are Fig. A.2 Comparison of y = tan θ, y = θ (radians), and y = sin θ Degrees Radians 360 2π π 180 (A.2) One of the advantages of radian measure can be seen in 57.2958 1 Fig. A.2. The functions sin θ,tanθ, and θ in radians are plot- 10.01745 ted vs. angle for angles less than 80 ◦. For angles less than 15 ◦, y = θ is a good approximation to both y = tan θ (2.3 % Since the angle in radians is the ratio of two distances, it is di- error at 15 ◦) and y = sin θ (1.2 % error at 15 ◦). -

02 Rutherford Scattering

Chapter 2 Rutherford Scattering Let us start from the one of the first steps which was done towards understanding the deepest structure of matter. In 1911, Rutherford discovered the nucleus by analysing the data of Geiger and Marsden on the scattering of α-particles against a very thin foil of gold. The data were explained by making the following assumptions. • The atom contains a nucleus of charge Z e, where Z is the atomic number of the atom (i.e. the number of electrons in the neutral atom), • The nucleus can be treated as a point particle, • The nucleus is sufficently massive compared with the mass of the incident α-particle that the nuclear recoil may be neglected, • That the laws of classical mechanics and electromagnetism can be applied and that no other forces are present, • That the collision is elastic. If the collision between the incident particle whose kinetic energy is T and electric charge ze (z = 2 for an α-particle), and the nucleus were head on, 13 α D the distance of closest approach D is obtained by equating the initial kinetic energy to the Coulomb energy at closest approach, i.e. z Z e 2 T = , 4πǫ 0D or z Z e 2 D = 4πǫ 0T at which point the α-particle would reverse direction, i.e. the scattering angle θ would equal π. On the other hand, if the line of incidence of the α-particle is a distance b, from the nucleus ( b is called the “impact parameter”), then the scattering angle will be smaller. -

Classical Electrodynamics

1 4 Radiation by Moving Charge s It is well known that accelerated charges emit electromagnetic radiation. In Chapter 9 we discussed examples of radiation by macroscopic time-varying charge and current densities, which are fundamentally charges in motion . We will return to such problems in Chapter 16 where multipole radiation is treated in a systematic way . But there is a class of radiation phenomena where the source is a moving point charge or a small number of such charges. In these problems it is useful to develop the formalism in such a way that the radiation intensity and polarization are related directly to properties of the charge's trajectory and motion . Of particular interest are the total radiation emitted, the angular distribution of radiation, and its frequency spectrum. For nonrelativistic motion the radiation is described by the well-known Larmor result (see Section 14.2) . But for relativistic particles a number of unusual and interesting effects appear . It is these relativistic aspects which we wish to emphasize . In the present chapter a number of general results are derived and applied to examples of charges undergoing prescribed motions, especially in external force fields . Chapter 15 deals with radiation emitted in atomic or nuclear collisions. 14.1 Lienard-Wiechert Potentials and Fields for a Point Charg e In Chapter 6 it was shown that for localized charge and current distri- butions without boundary surfaces the scalar and vector potentials can be written as f 1JM(x', 1) 6 (t' + R A``(X' t) - R - t) d3x' dt' (14. 1) C where R = (x - x'), and the delta function provides the retarded behavior 464 [Sect.