Eighth Letter to Uncle Sam Pokes Light Fun at the Soviet Union and Reserves His Sharpest Pen For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

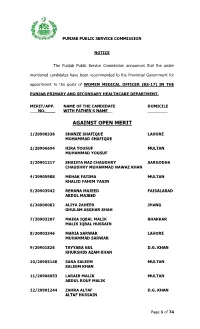

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

In the Name of Allah, Themostbeneficent

* n Z IN THE NAME OFALLAH, THE MOSTBENEFICENT, THE MOSTMERCIFUL IMPACTS OF ENGLISH CRITICISM ON PUNJABI CRITICISM 1947-2005 (An analytical and critical study) (Session 2003-2004) (Thesis Ph.D Punjabi) BB k$ SUBMITTED BY NAHEED QADIR Lecturer, Govt. Islamia College for women, Faisalabad SUPERVISOR Dr. NAHEED ZAMAN KHAN Associate Prof. Department of Punjabi, PUNJABI DEPARTMENT PUNJAB UNIVERSITY ORIENTAL COLLEGE LAHORE 2010 IMPACTS OF ENGLISH CRITICISM ON PUNJABI CRITICISM 1947-2005 (An analytical and critical study) (Session 2003-2004) (Thesis Ph.D Punjabi) aa Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirement of degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Punjabi, from Punjabi Department, in the University of the Punjab, for the year 2003 - 2004 SUBMITTED BY NAHEED QADIR Lecturer, Govt. Islamia College for women, Faisalabad SUPERVISOR Dr. NAHEED ZAMAN KHAN Associate Prof. Department of Punjabi. PUNJABI DEPARTMENT PUNJAB UNIVERSITY, ORIENTAL COLLEGE LAHORE 2010 Permission has been granted by the University of the Punjab, reference No. I/735-ACAD, Dated. 15.02.2010 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is a result of my individual research andIhave not submitted this thesis concurrently to any other University for any degree whatsoever.I NAHEED QADIR TOMYPARENTS WHO TAUGHTME TO CAREANDREASON AND TO TAYYABA FATIMA WHO PUTITALL TOGETHER AND MORE Contents Title Page No. Preface i-iv Chapter 1 Literary criticism: an over view 1. Introduction 1 2. Criticism and literature 4 3. Critical theory 7 4. types of literary criticism 9 o Legislative criticism o Judicial criticism o Theoretical criticism o Evaluative criticism o Historical criticism o Biographical criticism o Comparative criticism o Descriptive criticism o Impressionistic criticism o Textual criticism o Psychological criticism o Sociological and Marxist Criticism o Archetypal criticism 5. -

Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth

Winner List Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth Multan Division NIC ApplicantName GuardianName Address WinOrder Distt. Khanewal Jahanian (Bolan) Key Used: aghakhurm 3610102439763 ABDUL HAFEEZ M. HANIF 105/10R JAHANIAN DIST. 1 3610102595791 LIAQAT HUSSAIN ABDUL HAMEED THATA SADIQABAD, TEH JAHANIA, 2 DISTT. KHANWALA 3610102707797 GHAZANFAR HASSAN MOHAMMAD SHAKAR H NO. 225, BLOCK NO. 5, JAHANIAN 3 DISTT. KHANEWAL. 3610180513779 WASEEM ALI M. SARWAR CHAK NO. 121/10-R TEH. JAHANIA 4 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3520227188361 MOHAMMAD JAVED MOHAMMAD SHAFI FLAT NO 752C BLOCK Q MODEL TOWN 5 LAHORE 3610141795247 Muhammad Shahid Shahzada Zahid Raza Rahim Shah Road H/NO.164/A Jinnah 6 Abdil Jahanian D 3610132117859 MUHAMMAD DILSHAD ALI JAMSHAD ALI CHAK NO. 135/10R, TEHSEEL 7 JAHANIAN DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610102391383 TAHIR ABBAS AZIZ AHMED CHAK KHRIA POST 99-10R RAHEEM 8 SHAH 3610180588801 SOHAIL IJAZ IAJZ AHMED CHAK NO 116/10-R NEW TEH 9 JAHANIAN KHANEWAL 3610112010659 MOHAMMAD RIAZ FALIK SHER CHAK NO 157/10-R P/O JUNGLE 10 MARYALA JHASIL JAHANIA 3610166557189 MUHAMMAD THIR MUHAMMAD SLEEM CAHK NO 135/10R 11 3610171420543 TOQEER HUSSAIN SAEED SAEED AKHTAR CHAK NO. 132/10R, P.O. THATHA 12 SADIQ ABAD TEH JHANI 3610102461071 MUHAMMAD NASRULLAH KHUSHI MUHAMMAD BLOCK # 4 JAHANIAN KWL 13 3610181422213 HAFIZ ASIF JAVED ABDUL GHAFAR CHAK NO. 107/10-R TEH. JAHANIAN 14 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610115748627 MUHAMMAD ASIF MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO 114-10R JAHIANIAN DIST 15 KHANEWAL 3610154828857 ASIF BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD MAMTAZ LAKR MANDI TEH. JAHANIAN DISTT. 16 KHANEWAL 3610102391373 MUHAMMAD SARWAR MUHAMMAD NAZIR AHMED OPP BHATTI SERVICE STATION SIAL 17 TOWN JHN TEH JHN D 3610102750511 ASIF ISMAIL LIAQAT ALI CH. -

I (Persian Hons.)

Maulana Mazharul Haque Arabic & Persian University, Patna ALIM (Persian Hons.) Part - I Examination 2015 held in the month of April-2015 Page 1 of 81 Result Hons. Paper Subsi Compulsory Optional Composition Total Arabic Dinyat Total 100 Urdu Persian Total Grand Registration HP1 HP2 100 Paper 50 50 Remarks No 200 50 50 33 100 Total Roll No 100 100 15 Sl. Name 90 15 15 33 Marks 15 33 003 1 MD. NAYEEM UDDIN 150030400257 16201410373 69 75 144 28 34 62 Urdu Subsi 68 30 30 60 334 Pass 2 ZAMIRUL ISALM 150030400258 16201410372 55 61 116 22 24 46 Urdu Subsi 60 27 23 50 272 Pass 3 MAJEEDA BEGAM 150030400259 16201400328 A A 0 AA 0 Urdu Subsi A A A 0 0 Absent 4 RESHMI KHATOON 150030400260 16201400327 A A 0 AA 0 Urdu Subsi A A A 0 0 Absent 5 SADIYA SAMAR 150030400261 16201400326 66 82 148 32 35 67 Urdu Subsi 67 29 32 61 343 Pass 6 BIBI RASHNEEN PARWIN 150030400262 16201400325 60 72 132 25 36 61 Urdu Subsi 40 24 23 47 280 Pass 7 NAHEDA KHATOON 150030400263 16201400324 54 47 101 23 36 59 Urdu Subsi 41 18 23 41 242 Pass 8 SHAMA ANJUM 150030400264 16201400323 56 76 132 30 27 57 Urdu Subsi 60 30 22 52 301 Pass 9 SANOWER SABA 150030400265 16201400322 A A 0 AA 0 Urdu Subsi A A A 0 0 Absent 10 HEENA PARWEEN 150030400266 16201400321 56 76 132 26 26 52 Urdu Subsi 57 26 19 45 286 Pass 11 TAUFIQUE ALAM 150030400267 16201400320 54 72 126 28 32 60 Urdu Subsi 52 27 22 49 287 Pass 12 MD. -

Bihar Public Service Commission, Patna List of Ineligible Candidates for Asst.Professor, Urdu Under Advt

Bihar Public Service Commission, Patna List of Ineligible Candidates For Asst.Professor, Urdu under Advt. No. 46 /2014 S. No. ROLL No. NAME STATUS REMARKS 1. 46010011 TABASSUM ALIYA Claim of NET but Certificate not Attached Ineligible 2. 46010013 AMRITA KUMARI No NET, Ph.D. Without UGC Reg. 2009 Ineligible 3. 46010022 NIKHAT ARA No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 4. 46010023 WAJDAH TABASSUM No NET, Ph.D. Without UGC Reg. 2009 Ineligible 5. 46010024 NIYAZUDDIN ANSARI No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 6. 46010025 ABDUL QUDDUS No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 7. 46010026 LAL MAHAMMAD KHAN No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 8. 46010027 MD. ISA No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 9. 46010028 ZEBA JAMAL No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 10. 46010029 SALAMUDDIN No NET, Ph.D. WIthout UGC Reg. 2009 Ineligible 11. 46010030 MD. IMRAN No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 12. 46010032 SUCHIT KUMAR No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 13. 46010033 TANWEER ALAM ANSARI No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 14. 46010034 SAGHEERA SULTANA No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 15. 46010036 MD. FAZLUR RAHMAN No NET, Ph.D. Without UGC Reg.2009 Ineligible 16. 46010037 MD ZEYAUDDIN No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 17. 46010039 NUSRAT JAHAN No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 18. 46010040 SHAKIL AHMAD No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 19. 46010042 MS. ASHFAQUE ALAM No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 20. 46010043 MD. AMANULLAH No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 21. 46010046 ABDUL MANNAN No NET, No Ph.D. Ineligible 22. 46010047 NIKHAT PERWEEN No NET, No Ph.D. -

Alim Part - I Result 2012 Sl

Maulana Mazharul Haque Arabic & Persian University, Patna Alim Part - I Result 2012 Sl. Roll No Registration No Name of the Candidate Remarks 1100010400026 16200902049 MD ABBAS ANSARI Pending 2100010400031 16200902054 IMAM HASAN Absent 3100010400038 16200902061 MUSTAQUIM ANSARI Pass 4110010400059 16201000041 MD. AZIMUDDIN Fail 5110010400085 16201000071 MD.RAHIMUDDIN ANSARI Absent 6120010400001 16201111797 MD. SARTAZ ALAM Pass 7120010400002 16201108129 AFSHA SHAHEEN Pass 8120010400003 16201108128 GHAZALA SUBUHI Pass 9120010400004 16201108126 MD. AMANULLAH Pass 10120010400005 16201108125 SHAHNAZ KHATUN Fail 11120010400006 16201108124 SHAMINA BANO Pass 12120010400007 16201108123 FARZANA KHATOON Absent 13120010400008 16201108122 HUSNA BANO Pass 14120010400009 16201108121 NISHAT QADRI Pass 15120010400010 16201108117 ZEENAT AKHTAR Pass 16120010400011 16201108116 RABIBA KHATOON Pass 17120010400012 16201108115 SHAMIMA KHATOON Pass 18120010400013 16201108114 SHABINA PARVEEN Pass 19120010400014 16201108113 SHABNAM PERWEEN Pass 20120010400015 16201108112 FATMA KHATOON Fail 21120010400016 16201108109 NASRIN PERWEEN Pass 22120010400017 16201108108 TARANNUM AFTAB Absent 23120010400018 16201108107 SHARINA KHATOON Absent 24120010400019 16201108106 MD. SHAHREYAR ALAM Pass 25120010400020 16201108105 MD. SABIR MASURI Fail 26120010400021 16201108104 MD. EKRAMUL HAQUE Fail 27120010400022 16201108103 MD. ASHRAF ANSARI Fail 28120010400023 16201108102 AMJAD ALI Fail 29120010400024 16201108101 MD. AHSAN ALAM Pass 30120010400025 16201108100 MD. ZAFAR IQBAL Absent -

First Pak Modarab 14Th Dividend Unpaid Detail As on 31.12.2020

FIRST PAK MODARABA UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND D-14 2019-20 WARRANT NOS FOLIO NAME OF SHARE HOLDERS AMOUNT OF DIVIDEND STATUS 140001 1 MRS. ZOHRA BAI 10.00 UNPAID 140002 3 MR. GULNOOR 26.00 UNPAID 140003 10 MST. AMIR KHANUM 5.00 UNPAID 140004 14 MR. MOHAMMAD KHAN LODHI 26.00 UNPAID 140005 26 MR. MOHD SALIM MANSOORI 26.00 UNPAID 140006 27 MR. AFAQ ALI 2.00 UNPAID 140007 29 MR. ABBAS 6.00 UNPAID 140008 32 MR. SIRAJ 7.00 UNPAID 140009 33 MR. MOHAMMAD AFAQ 7.00 UNPAID 140010 41 MR. S. SHAKIL ASHRAF 1.00 UNPAID 140011 45 MR. A. SATTAR KAMDAR 24.00 UNPAID 140012 46 MRS. HAMIDA BANOO 24.00 UNPAID 140013 83 MR. MOHD HANIF 2.00 UNPAID 140014 84 MR. GHULAM ABBAS 2.00 UNPAID 140015 86 MRS. KAUSAR PARVEEN 6.00 UNPAID 140016 90 MR. MUSHTAQ 10.00 UNPAID 140017 92 MRS. NASERA BANO 2.00 UNPAID 140019 100 MST. FARIDA YAQOOB ABDUL SATTAR 1.00 UNPAID 140020 103 MR. MOHAMMED YOUSUF 26.00 UNPAID 140021 116 MRS. ZAHID BEGUM 11.00 UNPAID 140022 123 MRS. ZARINA SULTAN 2.00 UNPAID 140023 125 MR. FAZAL MAHMOOD 2.00 UNPAID 140024 131 MISS ZAHIDA PERVEEN 6.00 UNPAID 140025 137 SYED AZIZ AHMED 6.00 UNPAID 140026 157 MRS. KULSOOM 6.00 UNPAID 140027 162 MR. ABDUL RASHEED 26.00 UNPAID 140028 181 MRS. YASMIN 26.00 UNPAID 140029 194 MR. ANIS AHMAD KHALID 6.00 UNPAID 140030 198 MR. ISMAIL VOHRA 26.00 UNPAID 140031 199 MR. ZAKARIA UMAR 6.00 UNPAID 140032 200 MR. -

MAULANA AZAD NATIONAL URDU UNIVERSITY (A Central University, Accredited "A" Grade by NAAC) Gachibowli, Hyderabad - 500 032 Directorate of Admissions

MAULANA AZAD NATIONAL URDU UNIVERSITY (A Central University, accredited "A" Grade by NAAC) Gachibowli, Hyderabad - 500 032 Directorate of Admissions PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR B.Ed. (Distance Mode) 2017-18 Candidates who appeared for the B.Ed. (Distance Mode) Entrance Test for Admission to 2017-18 Session may note their ranks in the list given below. All candidates desirous for seeking admission should appear for verification of documents at the Counselling Centre chosen by them as per Cfoaltloewgoinrgy schedule: Overall Date & Time Rank 20-06-2018 09:00 a.m. General and OBC 1-1500 Candidate belonging to SC, ST, Person with Disabilities, Sports, All ranks and NCC 0O9n:l0y0thao.sme.coannd2id1a-0te6s-2w0h1o8a(rCeacnledaidreadtefoarrecoaudnvseislleindgtoaftmerakveriafricraatniognemofetnhtesirfodrocthumeiernsttsamy uosnt trhepeoirrtowfonr)c.ounselling at the same Counselling Centre where documents were verified sharp at During Counselling, candidaCtheowicilel emxaedrceisaettthheeirtcihmoeicoeftoCocuhnoosesellitnhge Lshearlnl ebreSfuinpaplor&t nCeonctlraei/mProofgcrhamangCenintrteh(esuLbSCje/cPt Ctoshsaelaltbseaevnaitlearbtialiitny)edwahtelnatcearllsetdagdeu.ring the counselling as per their rank in their respective category. Candidates must bring the following Original Certificates/Documents for verification and their self- attested photocopies for submission at the Counselling session: 1. S.S.C./10th Class Certificate or other relevant document in respect of Date of Birth, Name, and Father's name 2. Original/Provisional Bachelor’s Degree Certificate and Marks memo (3 Years) of any university recognised by UGC. 3. Certificate showing proof of having studied Urdu as a subject or medium of study at X or its equivalent or higher level. 4. Service Certificate issued and attested by the Head master in respect of candidate being “trained in-service teacher” (The Proforma of the Employment Certificate is given in Annexure-III) OR Certificate showing proof of having completed NCTE recognized teacher training programme through face to face mode. -

PULWAMA 2Nd Quarter 2018-19 JSY Mother Beneficiries Line Listing

PULWAMA_2nd Quarter_ 2018-19 JSY Mother Beneficiries Line Listing Name Of Date of Amount S.NO W/O R/O Contact No Cheque No Date of cheque Beneficiary Delivery (Rs) 798 NIGEENA FAROOQ AHMAD MIR DRUSOO 7051677413 23/4/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 799 MEHMOODA BHAT RAYEES AHMAD PINGLANA 9906890358 25/4/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 800 NIGEENA JAVAID AHMAD WAGAY KOIL 9697768582 14/3/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 801 SARA SHOWKAT ALI RATNIPORA 9596261713 14/6/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 802 HASEENA RIYAZ AHMAD BHAT CHANDGAM 9622817736 25/4/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 803 MEHMOODA AB MAJEED MALIK WASOORA 9622939052 23/10/2017 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 804 MAHJABEENA SHAMEEM AHMAD KUMAR GANGIPORA 9596356075 14/6/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 805 SAMEERA BILAL AHMAD BHAT TALANGAM 9906952658 28/2/2018 1400 C071803763537 7/10/2018 806 NASEERA YAWAR AHMAD BHAT THOKERPORA 9622706689 11/5/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 807 SUMI MUZAFFER AHMAD HURPORA 9905765417 16/5/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 808 NAHIDA FAYAZ AHMAD SHEIKH MURRAN 9906529577 22/5/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 809 SHABNUM ZAHOOR AHMAD PARAY SHOPIAN 9596428107 19/3/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 810 HASEENA MIR MOHD SHAFI AWANGUND N/A 7/9/2015 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 811 FEHMEEDA MOHD ALTAF SOFI NEWA 9858804199 15/2/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 812 FEHMEEDA JAVAID AHMAD DHOBI WASHBUGH 9858049293 11/6/2018 1000 C071815273111 8/29/2018 813 MASRAT ABID HUSSAIN WANI ARGICHEK 7051676453 25/6/2018 1400 C071815273111 8/29/2018 814 AFROOZA -

KNG EDWARD Medical UNIVERSITY, Lahore €Fu

# KNG EDWARD MEDIcAL UNIVERSITY, LAHoRE €fu . oFFlcE oF THE CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS H". ----ll-5.5;c.e;KEMU Dated: I I az-zotg RESULT NOTIFICAT!ON JOTNT CENTRALTZED ADMTSSTON TEST (JGAT) FOR ADMISSION !N MD/MS PROGRAMME The result of the following candidates of Joint Centralized Admission Test (JCAT) for admission in MD/MS Programme held on 10-02-2019 is declared as under:- Sr. Obtained PMDC No Roll No. Name of Candidate Father Name Status No. Marks 612 84919-P 1910612 Ayesha Javaid Javaid lqbal 140 Fail otJ I 9'1061 3 Birat Acharya Tajrat Acharya 138 Fail 614 87738-P 1910614 Neelam Arif Sheikh Muhammad Arif 114 Fail 615 87653-P 1910615 lrbaz Ur Rehman Muhammad Zubair Awan 134 Fail o to 1910616 Mohamamd Naeem Amin Khan 114 Fail '130 617 75310-P 1910617 Sajjad Ahmad Manzoor Ahmad Fail 618 85005-P 1910618 Sonia Toqeer M. Saleem Faisal 140 Fail 619 80739-P 1910619 Junaid Amin Muhammad Amin 90 Fail Syeda Zarghouna 620 84522-P 1910620 Syed Azam Ali Naqvi 140 Fail Fatima 621 86908-P 1910621 Hassan Khalid Abdul Khalid 118 Fail 622 87682-P 1910622 Sidra Ahmed Muhammad Javed 130 Fail 623 1910623 Baz Mohammad Haji Noor Khan 72 Fail 624 85260-P 1910624 Sidra lshaq Muhammad lshaq tJo Fail Muhammad Qamar 625 83860-P 1910625 Muhammad Nazeer 104 Fail Nazeer 626 89552-P 1910626 Sara ljaz ljaz Ahmad 140 Fail Mukhtar Ahmed Sheikh 150 Pass 627 88149-P 1910627 Luqman Mukhtar Anium ot6 80606-P 1910628 Ghania Rehman Rehman Ullah 114 Fail 629 78440-P 1910629 Abid Hussain Akhtar Hussain Shakir 136 Fail 630 88457-P 1910630 Hamna Arif Muhammad Arif Ch. -

Najm Hosain Syed: a Literary Profile

255 Zubair Ahmad: Najm Hosain Syed Najm Hosain Syed: A Literary Profile Zubair Ahmad Punjabi Poet from Lahore ________________________________________________________________ This article provides an introduction to the writings of Najm Hosain Syed, a renowned Punjabi author. From 1965 onward, Syed has published poetry, plays, and literary criticism. He has also made an outstanding contribution toward raising the status of Punjabi language in West Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ It is not easy to find an educated person in West Punjab who does not know Najm Hosain Syed or has not read his writings. He has mentored many writers and guided others in their readings of Punjabi literature. At the same time, he is not an insider in the West Punjabi academic structures and none of his books are prescribed in the university syllabi. Syed is a shy person, who does not like to leave Lahore, does not give interviews, does not appear on television or radio, and publishes his books with relatively unknown publishers. This essay aims to introduce the writings of this enigmatic person. Najm Hosain Syed was born in 1936 in an influential Qadri family of Batala in East Punjab. The Syeds moved to Lahore after the partition where young Najm was educated. In 1958, he completed his Masters in English at Forman Christian College. He joined the Pakistan civil services building a distinguished career from which he retired in 1995. In the years that followed Partition, Punjabi was relegated to a position of relative insignificance in West Punjab. With the exception of Trinjhanh (Girls’ Gathering) by Ahmad Rahi in 1953, Punjabi literature did not see any major work. -

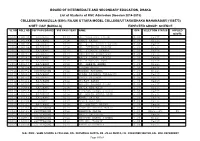

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Dhaka

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA List of Students of HSC Admission (Session 2014-2015) COLLEGE/THANA/ZILLA (EIIN): RAJUK UTTARA MODEL COLLEGE/UTTARA/DHAKA MAHANAGARI (108573) SHIFT: DAY (BANGLA) EXPECTED GROUP: SCIENCE SL NO ROLL NO SSC PASS BOARD SSC PASS YEAR NAME GPA SELECTION STATUS APPLIED QUOTA 00001 100102 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. TAUHIDUL ISLAM 5.00 Merit 00002 100188 RAJSHAHI 2014 SAMIT HASAN 5.00 Merit 00003 100193 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. A. B. SIDDIK KAYUM 5.00 Merit 00004 100194 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. IFTEKHAR HASSAN 5.00 Merit 00005 100206 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. SIJANUR RAHMAN 5.00 Merit 00006 100241 RAJSHAHI 2014 DWAIPAYAN CHOWDHURY 5.00 Merit 00007 100243 RAJSHAHI 2014 HASIN ISHRAQ SAUMIK 5.00 Merit 00008 100250 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. MINHAJUL AWAL 5.00 Merit 00009 100253 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. SABBIR AHMED 5.00 Merit 00010 100298 CHITTAGONG 2014 BIKONA GHOSH 5.00 Merit 00011 100361 CHITTAGONG 2014 FABIHA RAIHANA 5.00 Merit 00012 100363 RAJSHAHI 2014 SUBAH RAIHANA TABASSUM 5.00 Merit 00013 100367 RAJSHAHI 2014 FARIA SHOBNOM 5.00 Merit 00014 100412 RAJSHAHI 2014 NUSRAT ZARIN 5.00 Merit 00015 100432 RAJSHAHI 2014 NAFISA SABNAM SHAMA 5.00 Merit 00016 100489 RAJSHAHI 2014 NAJIA MEHJABIN 5.00 Merit 00017 100915 SYLHET 2014 DIPAYON KUMAR SIKDER 5.00 Merit 00018 101165 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. RAGIB NIHAL ABIR 5.00 Merit 00019 101166 RAJSHAHI 2014 AHMED SHITAB 5.00 Merit 00020 101299 DHAKA 2014 AFRIN SULTANA 5.00 Merit 00021 101313 RAJSHAHI 2014 MD. RAKIBUL HASAN 5.00 Merit 00022 102365 CHITTAGONG 2014 TANMINA AKHTER MUNIA 5.00 Merit 00023 102586 CHITTAGONG 2014 FAHMIDA FAIZA 5.00 Merit-FQ FQ 00024 102962 CHITTAGONG 2014 NABIL SALEHEEN 5.00 Merit 00025 102965 CHITTAGONG 2014 SHOVITO BARUA SOUMMA 5.00 Merit 00026 103003 CHITTAGONG 2014 MIR MD.