Progressives and “Perverts” Partition Stories and Pakistan’S Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muhammad Umar Memon Bibliographic News

muhammad umar memon Bibliographic News Note: (R) indicates that the book is reviewed elsewhere in this issue. Abbas, Azra. ìYouíre Where Youíve Always Been.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. Words Without Borders [WWB] (November 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/youre-where-youve-alwaysbeen/] Abbas, Sayyid Nasim. ìKarbala as Court Case.î Translated by Richard McGill Murphy. WWB (July 2004). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/karbala-as-court-case/] Alam, Siddiq. ìTwo Old Kippers.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/two-old-kippers/] Alvi, Mohammad. The Wind Knocks and Other Poems. Introduction by Gopi Chand Narang. Selected by Baidar Bakht. Translated from Urdu by Baidar Bakht and Marie-Anne Erki. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2007. 197 pp. Rs. 150. isbn 978-81-260-2523-7. Amir Khusrau. In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Translated by Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2011. 224 pp. Rs. 450. isbn 9780670082360. Amjad, Amjad Islam. Shifting Sands: Poems of Love and Other Verses. Translated by Baidar Bakht and Marie Anne Erki. Lahore: Packages Limited, 2011. 603 pp. Rs. 750. isbn 9789695732274. Bedi, Rajinder Singh. ìMethun.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/methun/] Chughtai, Ismat. Masooma, A Novel. Translated by Tahira Naqvi. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2011. 152 pp. Rs. 250. isbn 978-81-88965-66-3. óó. ìOf Fists and Rubs.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (Sep- tember 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/of-fists-and-rubs/] Granta. 112 (September 2010). -

Literary Criticism and Literary Historiography University Faculty

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected]) Title Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. First Name Ali Last Name Javed Photograph Designation Reader/Associate Professor Department Urdu Address (Campus) Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) C-20, Maurice Nagar, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 27662108 Mobile 9868571543 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 1983 Thesis topic: British Orientalists and the History of Urdu Literature Topic: Jaafer Zatalli ke Kulliyaat ki M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1979 Tadween M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1977 Subjects: Urdu B.A. University of Allahabad 1972 Subjects: English Literature, Economics, Urdu Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Zakir Husain PG (E) College Lecturer 1983-98 Teaching and research University of Delhi Reader 1998 Teaching and research National Council for Promotion of Director April 2007 to Chief Executive Officer of the Council Urdu Language, HRD, New Delhi December ’08 Research Interests / Specialization Research interests: Literary criticism and literary historiography Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) (a) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature 2. Poetry: Ghalib, Josh, Firaq Majaz, Nasir Kazmi 3. Prose: Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mohammed Husain Azad, Sir Syed (b) M. Phil: Literary Criticism Honors & Awards www.du.ac.in Page 1 a. Career Awardee of the UGC (1993). Completed a research project entitled “Impact of Delhi College on the Cultural Life of 19th Century” under the said scheme. -

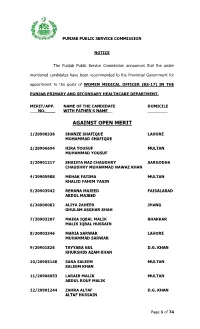

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction Ismat Chughtai, Sa'adat Hasan Manto

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction I , Sa‘adat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chandar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Ali Sardar Jafri, Majaz, Meeraji, and Khawaja Ahmed Abbas. These are some of the names that come to mind when we think of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and modern Urdu literature. But how many people know that every one of these writers was also involved with the Bombay film indus- try and was closely associated with film directors, actors, singers and pro- ducers? Ismat Chughtai’s husband Shahid Latif was a director and he and Ismat Chughtai worked together in his lifetime. After Shahid’s death Ismat Chughtai continued the work alone. In all, she wrote scripts for twelve films, the most notable among them ◊iddµ, Buzdil, Sån® kµ ≤µ∞y≥, and Garm Hav≥. She also acted in Shyam Benegal’s Jun∑n. Khawaja Ahmed Abbas made a name for himself as director and producer for his own films and also by writing scripts for some of Raj Kapoor’s best- known films. Manto, Krishan Chandar and Bedi also wrote scripts for the Bombay films, while all of the above-mentioned poets provided lyrics for some of the most alluring and enduring film songs ever to come out of India. In remembering Kaifi Azmi, Ranjit Hoskote says that the felicities of Urdu poetry and prose entered the consciousness of a vast, national audience through the medium of the popular Hindi cinema; for which masters of Urdu prose, such as Sadat [sic] Hasan Manto, wrote scripts, while many of the Progressives, Azmi included, provided lyrics. -

Modernism and the Progressive Movement in Urdu Literature

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No. 3; March 2012 Modernism and the Progressive Movement in Urdu Literature Sobia Kiran Asst. Professor English Department LCWU, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract The paper aims at exploring salient features of Progressive Movement in Urdu literature and taking into account points of comparison with Modernism in Europe. The paper explores evolution of Progressive Movement over the years and traces influence of European Modernism on it. Thesis statement: The Progressive Movement in Urdu literature was tremendously influenced by European Modernism. 1. Modernism The term Modernism is used to distinguish the literature that developed out of the First World War. Modernism deliberately broke with Western traditions of certainty. It came into being as they were collapsing. It challenged all the old modes. Important precursors of Modernism were Nietzsche, Freud and Marx who in different degrees rejected certainties in religion, philosophy, psychology and politics. They came to distrust the stability and order offered in earlier literary works. It broke with literary conventions. Like any new movement it rebelled against the old. It was nihilistic and tended to believe in its own self sufficiency. “Readers were now asked to look into themselves, to establish their real connections with the world and to ignore the rules of religion and society. Modernism wants therefore to break the old connections, because it believes that these are artificial and exploitative…” (Smith, P.xxi) The people are provoked to think and decide for themselves. They are expected to reconstruct their moralities. The concern for social welfare continued. “Every period has its dominant religion and hope…and “socialism” in a vague and undefined sense was the hope of the early twentieth century.”(Smith xiii) Marxism suffered an eclipse after the Second World War. -

CCIM-11B.Pdf

Sl No REGISTRATION NOS. NAME FATHER / HUSBAND'S NAME & DATE 1 06726 Dr. Netai Chandra Sen Late Dharanindra Nath Sen Dated -06/01/1962 2 07544 Dr. Chitta Ranjan Roy Late Sahadeb Roy Dated - 01-06-1962 3 07549 Dr. Amarendra Nath Pal late Panchanan Pal Dated - 01-06-1962 4 07881 Dr. Suraksha Kohli Shri Krishan Gopal Kohli Dated - 30 /05/1962 5 08366 Satyanarayan Sharma Late Gajanand Sharma Dated - 06-09-1964 6 08448 Abdul Jabbar Mondal Late Md. Osman Goni Mondal Dated - 16-09-1964 7 08575 Dr. Sudhir Chandra Khila Late Bhuson Chandra Khila Dated - 30-11-1964 8 08577 Dr. Gopal Chandra Sen Gupta Late Probodh Chandra Sen Gupta Dated - 12-01-1965 9 08584 Dr. Subir Kishore Gupta Late Upendra Kishore Gupta Dated - 25-02-1965 10 08591 Dr. Hemanta Kumar Bera Late Suren Bera Dated - 12-03-1965 11 08768 Monoj Kumar Panda Late Harish Chandra Panda Dated - 10/08/1965 12 08775 Jiban Krishna Bora Late Sukhamoya Bora Dated - 18-08-1965 13 08910 Dr. Surendra Nath Sahoo Late Parameswer Sahoo Dated - 05-07-1966 14 08926 Dr. Pijush Kanti Ray Late Subal Chandra Ray Dated - 15-07-1966 15 09111 Dr. Pratip Kumar Debnath Late Kaviraj Labanya Gopal Dated - 27/12/1966 Debnath 16 09432 Nani Gopal Mazumder Late Ramnath Mazumder Dated - 29-09-1967 17 09612 Sreekanta Charan Bhunia Late Atul Chandra Bhunia Dated - 16/11/1967 18 09708 Monoranjan Chakraborty Late Satish Chakraborty Dated - 16-12-1967 19 09936 Dr. Tulsi Charan Sengupta Phani Bhusan Sengupta Dated - 23-12-1968 20 09960 Dr. -

FACULTY : COLLEGE : 1 of Page SINDH E-CENTRALIZED

SINDH E-CENTRALIZED COLLEGE ADMISSION POLICY 2017 PLACEMENT IN XI ON MERIT UNDER SECCAP-2017 PRINT DATE : 04/09/2017 FACULTY : Pre-Engineering - Female Page 1 of 9 COLLEGE : 201 ABDULLAH GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KARACHI ADMISSION START AT = 751 ADMISSION CLOSED AT = 591 # ROLL - YEAR Name Marks 1 483160 - 2017 TOOBA SHAKIL D/O SHAKIL AKHTAR 751 2 483179 - 2017 NADIA SALEEM D/O MUHAMMAD SALEEM 742 3 470543 - 2017 AQSA SHERAZ D/O MUHAMMAD KHALID SHEROZ 739 4 483178 - 2017 MISBAH D/O ABDUL RAOOF 737 5 481587 - 2017 AYESHA D/O MUHAMMAD IQBAL 724 6 483165 - 2017 FAZEELA QADIR D/O ABDUL QADIR 722 7 484420 - 2017 SAMINA D/O SHAMIM AKHTER 714 8 433353 - 2017 DANIA AHMED D/O SALAHUDDIN AHMED QURAISHI 713 9 439093 - 2017 FABIHA IKHLAQ D/O MUHAMMAD IKHLAQ 709 10 444873 - 2017 FABIHA NADIR D/O NADIR MUHAMMAD QURESHI 708 11 484046 - 2017 AYESHA FAROOQ D/O MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 708 12 432060 - 2017 KHADIJA D/O FAKHRUDDIN 708 13 433941 - 2017 MARIA MEHMOOD D/O MEHMOOD ASHRAF 706 14 446166 - 2017 BIBI IQRA D/O SHAKEEL AHMED 705 15 485623 - 2017 MUBASHRA SABIR D/O SABIR AHMED 705 16 478101 - 2017 NAYAB SHAH D/O SYED WAQAR HUSSAIN SHAH 704 17 484023 - 2017 MISBAH ANSARI D/O IKHLAQ AHMED 704 18 429700 - 2017 HAREEM BINT E ZIA D/O AHMED ZIA UDDIN 703 19 430944 - 2017 NIMRA KHANUM D/O MUHAMMAD SHARIF ULLAH KHAN 703 20 478099 - 2017 IRSA D/O GHULAM RASOOL 702 21 479586 - 2017 DUA ZAHRA JAFRI D/O AZHAR ABBAS JAFRI 702 22 484249 - 2017 MARIA NOUREEN D/O SHAFI ALAM 702 23 477809 - 2017 MARIYAM D/O MUHAMMAD ISHAQ 701 24 482955 - 2017 LAIBA ISLAM RANA D/O SHOUKAT ISLAM -

A Linguistic Critique of Pakistani-American Fiction

CULTURAL AND IDEOLOGICAL REPRESENTATIONS THROUGH PAKISTANIZATION OF ENGLISH: A LINGUISTIC CRITIQUE OF PAKISTANI-AMERICAN FICTION By Supervisor Muhammad Sheeraz Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan 47-FLL/PHDENG/F10 Assistant Professor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English To DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD April 2014 ii iii iv To my Ama & Abba (who dream and pray; I live) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe special gratitude to my teacher and research supervisor, Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan. His spirit of adventure in research, the originality of his ideas in regard to analysis, and the substance of his intellect in teaching have guided, inspired and helped me throughout this project. Special thanks are due to Dr. Kira Hall for having mentored my research works since 2008, particularly for her guidance during my research at Colorado University at Boulder. I express my deepest appreciation to Mr. Raza Ali Hasan, the warmth of whose company made my stay in Boulder very productive and a memorable one. I would also like to thank Dr. Munawar Iqbal Ahmad Gondal, Chairman Department of English, and Dean FLL, IIUI, for his persistent support all these years. I am very grateful to my honorable teachers Dr. Raja Naseem Akhter and Dr. Ayaz Afsar, and colleague friends Mr. Shahbaz Malik, Mr. Muhammad Hussain, Mr. Muhammad Ali, and Mr. Rizwan Aftab. I am thankful to my friends Dr. Abdul Aziz Sahir, Dr. Abdullah Jan Abid, Mr. Muhammad Awais Bin Wasi, Mr. Muhammad Ilyas Chishti, Mr. Shahid Abbas and Mr. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

Travelogues of China in Urdu Language: Trends and Tradition

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 6(9): 163-166, 2016 ISSN: 2090-4274 © 2016, TextRoad Publication Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com Travelogues of China in Urdu Language: Trends and Tradition Muhammad Afzal Javeed 1,a , Qamar Abbas 2, Mujahid Abbas 3, Farooq Ahmad 4, Dua Qamar 5 1,a Department of Urdu, Govt. K.A. Islamia Degree College, Jamia Muhammadi Sharif, Chiniot, Pakistan, 2,5 Department of Urdu, Govt. Postgraduate College, Bhakkar, Pakistan, 3Department of Urdu, Qurtuba University of Science and Technology, D. I. Khan, Pakistan, 4Punjab Higher Education Department, GICCL, Lahore, Pakistan, Received: June 8, 2016 Accepted: August 15, 2016 ABSTRACT Many political and literary delegations visit China from Pakistan. Individual people also travel this important country for different purposes. There are many important Urdu travelogues about China. In these travelogues information of political, social, agricultural, educational, cultural and religious nature is included. The history and revolutionary background of China is also discussed. Some of these travelogues have a touch of humour. Majority of the travelogues of China are of official visits of different delegations. KEYWORDS : Urdu Literature, Urdu Travelogue, Urdu Travelogues of China, Urdu Travelogue trends, 1. INTRODUCTION China is an important country of the world due to its economic growth. It is also important for Pakistan not only for its neighbour position but also for its friendly relations. It has a great historical background and a very strong civilization. People of Pakistan visit this country every year due to this friendship of both the countries. Both the countries exchange their educational resources for their people. -

Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur SYLLABUS for SCREENING TEST for the POST of ASSISTANT PROFESSOR in URDU - Language & Literature

Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur SYLLABUS FOR SCREENING TEST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT PROFESSOR IN URDU - Language & Literature Unit – I (a) Western Hindi and its dialects namely : Braj Bhasha, Haryanwi and Khari Boli. (b) Role of Rajasthani in the development of Urdu. (c) Persio-Arabic elements in Urdu. (d) Different theories of the origin of Urdu Language. Unit – II (a) Classical geners of Urdu Poetry : Ghazal, Qasida, Marsiya, Masnavi, Rubai. (b) Modern generes of Urdu Poetry : Nazm – Blank Verse, Free Verse. (c) Important generes of Urdu Prose : Dastan, Novel, Short Story (Afsana), Drama, Biography. (d) Two classical Schools of Urdu Poetry : (i) Delhi School of Poetry. (ii) Lucknow School of Poetry. Unit – III (a) Salient Features of Daccani Language and important poets of Daccani. (b) Important Prose writers upto Mirza Ghalib. (c) Aligarh Movement and its contribution in the development of Urdu Literature. (d) Romantic/Progressive Movement and its contribution in the development of Modern Urdu Literature. Unit – IV Important Poets and Prose Writers (a) Poets (Nazm) – Nazir, Akabarabadi, Hali, Azad, Chakbast, Durga Sahay Suroor, Akbar Allahabadi, Iqbal Joseh, Faiz, Meeraji, Noon Meem Rashid. (b) Poets (Ghazal)_ - Wali, Dard, Meer, Nasikh, atish, Ghalib, Momin, Dagh, Hasrat, Fani, Asghar, Firaq, Nasir Kazmi. (c) Prose Writers (Fiction) – Mulla Wajhi, Meer Amman, Rajab Ali Beg Suroor, Nazir Ahmad, Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Bedi, Quarratul Ain Hyder, Surendar Parkash. (d) Prose Writers (Non-fiction ) - Fazli, Ghalib, Mohd. Hussain Azad, Mehdi Ifadi, Sir Syed, Hali, Shibli, Maulana Azad, Rashid Ahmad Siddique, Mushtaq Ahmad Yusufi. Unit – V (a) Impact of West on Urdu Literature.