English in ASEAN: Implications for Regional Multilingualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Collins Malay Dialect Research in Malysia: the Issue of Perspective

J. Collins Malay dialect research in Malysia: The issue of perspective In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 145 (1989), no: 2/3, Leiden, 235-264 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 12:15:07AM via free access JAMES T. COLLINS MALAY DIALECT RESEARCH IN MALAYSIA: THE ISSUE OF PERSPECTIVE1 Introduction When European travellers and adventurers began to explore the coasts and islands of Southeast Asia almost five hundred years ago, they found Malay spoken in many of the ports and entrepots of the region. Indeed, today Malay remains an important indigenous language in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand and Singapore.2 It should not be a surprise, then, that such a widespread and ancient language is characterized by a wealth of diverse 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the English Department of the National University of Singapore (July 22,1987) and to the Persatuan Linguistik Malaysia (July 23, 1987). I would like to thank those who attended those presentations and provided valuable insights that have contributed to improving the paper. I am especially grateful to Dr. Anne Pakir of Singapore and to Dr. Nik Safiah Karim of Malaysia, who invited me to present a paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Azhar M. Simin and En. Awang Sariyan, who considerably enlivened the presentation in Kuala Lumpur. Professor George Grace and Professor Albert Schiitz read earlier drafts of this paper. I thank them for their advice and encouragement. 2 Writing in 1881, Maxwell (1907:2) observed that: 'Malay is the language not of a nation, but of tribes and communities widely scattered in the East.. -

WO/GA/24/4 REV.: Use of Portuguese As a Working Language of WIPO

E WO/GA/24/4 Rev. ORIGINAL: English WIPO DATE: July 19, 1999 WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION WIPO GENERAL ASSEMBLY Twenty-Fourth (14th Ordinary) Session Geneva, September 20 to 29, 1999 USE OF PORTUGUESE AS A WORKING LANGUAGE OF WIPO Document prepared by the International Bureau 1. In two letters dated November 11, 1998, and January 25, 1999, the President of Portugal’s National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), writing in the name of the seven countries whose official language is Portuguese, requested the Director General of WIPO to include, on the agenda of the next session of the WIPO General Assembly, consideration of the possibility of adopting Portuguese as a working language of WIPO. 2. In support of this request, the President of INPI stated that Portuguese is the fifth most widely spoken language in the world, being spoken by 200 million people, that all seven Portuguese–speaking countries are now party to the WIPO Convention and the main treaties administered by WIPO and that the majority of Portuguese speakers are nationals of developing countries. He also noted that the use of Portuguese as a working language of WIPO would reinforce and enhance the participation of Portuguese speaking countries in the development activities conducted by WIPO for their benefit and would reflect the new dynamic spirit of WIPO’s cooperation for development program. 3. It is recalled that Article 6(2)(vii) of the Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization provides that the General Assembly shall “determine the working languages of the Secretariat, taking into consideration the practice of the United Nations.” WO/GA/24/4 Rev. -

Working in a Foreign Language

Master in Learning and Communication in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts WORKING IN A FOREIGN LANGUAGE: Case study of employees’ perceptions in a Luxembourg-based multinational company using English as a lingua franca Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ingrid de Saint-Georges Master Thesis submitted by: Yelena Radley Luxembourg June 2016 Abstracts With the globalisation of business and diversification of the workforce, an increasing number of companies implement a corporate language policy based on the use of a lingua franca, often English. Thus more and more people face the challenges of simultaneous socialisation into a new corporate and linguistic environment, and of re-inventing themselves as competent articulate professionals through the medium of a foreign language. While a number of studies have concentrated on the management angle of corporate communication, fewer seem to focus on the language-related experiences of the employees in a multinational company. Adopting a sociolinguistic approach, this study seeks to explore the implications of working in a foreign language through the perceptions of a sample of employees at a multinational IT company based in Luxembourg and using English as a lingua franca. The qualitative content analysis of the data obtained in the course of 6 semi-structured interviews provides insights into the ways the employees construct and negotiate their daily linguistic reality. The study examines their attitudes to working in a foreign language (English as a lingua franca or other language) and outlines the perceived benefits, challenges and coping strategies. Special attention is paid to discourses linking language to power and professionalism. The adaptation to professional functioning in a foreign language is presented as a continuum, tracing the journey from overcoming initial challenges to achieving ‘linguistic well-being’. -

Switzerland 4Th Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 15 December 2009 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fourth Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SWITZERLAND Periodical report relating to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages Fourth report by Switzerland 4 December 2009 SUMMARY OF THE REPORT Switzerland ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Charter) in 1997. The Charter came into force on 1 April 1998. Article 15 of the Charter requires states to present a report to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe on the policy and measures adopted by them to implement its provisions. Switzerland‘s first report was submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in September 1999. Since then, Switzerland has submitted reports at three-yearly intervals (December 2002 and May 2006) on developments in the implementation of the Charter, with explanations relating to changes in the language situation in the country, new legal instruments and implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers and the Council of Europe committee of experts. This document is the fourth periodical report by Switzerland. The report is divided into a preliminary section and three main parts. The preliminary section presents the historical, economic, legal, political and demographic context as it affects the language situation in Switzerland. The main changes since the third report include the enactment of the federal law on national languages and understanding between linguistic communities (Languages Law) (FF 2007 6557) and the new model for teaching the national languages at school (—HarmoS“ intercantonal agreement). -

'Official' Languages of the Independent Asia-Pacific

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities January 2019 'National' and 'Official' Languages of the Independent Asia-Pacific Rowena G. Ward University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Recommended Citation Ward, Rowena G., "'National' and 'Official' Languages of the Independent Asia-Pacific" (2019). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 4025. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/4025 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 'National' and 'Official' Languages of the Independent Asia-Pacific Abstract In November 2018 New Caledonians went to the polls to vote on whether the French territory should become an independent state. In accordance with the terms of the 1998 Noumea Accord between Kanak pro-independence leaders and the French government, New Caledonians will have the opportunity to vote on the same issue again in 2020 and should they vote for independence, a new state will emerge. In another part of Melanesia, the people of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville (ARB) will vote on 23 November 2019 on whether to secede from Papua New Guinea and form an independent state. With the possibility of two new independent states in the Pacific, the possible political and economic consequences of a vote for independence have attracted attention but little consideration has been paid to the question of which languages might be used or adopted should either territory, or both, choose independence. -

U.S.-Japan-China Relations Trilateral Cooperation in the 21St Century

U.S.-Japan-China Relations Trilateral Cooperation in the 21st Century Conference Report By Brad Glosserman Issues & Insights Vol. 5 – No. 10 Honolulu, Hawaii September 2005 Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, the Pacific Forum CSIS (www.csis.org/pacfor/) operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic, business, and oceans policy issues through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate areas. Founded in 1975, it collaborates with a broad network of research institutes from around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating project findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and members of the public throughout the region. Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements iv Executive Summary v Report The year in review 1 Energy security and the impact on trilateral cooperation 4 Issues in the bilateral relationship 6 Opportunities for cooperation 9 Selected Papers United States, Japan, and China Relations: Trilateral Cooperation in the 21st Century by Yoshihide Soeya 15 Chinese Perspectives on Global and Regional Security Issues by Gao Zugui 23 Sino-U.S. Relations: Healthy Competition or Strategic Rivalry? by Bonnie S. Glaser 27 Sino-U.S. Relations: Four Immediate Challenges by Niu Xinchun 35 Sino-Japanese Relations 60 Years after the War: a Japanese View by Akio Takahara 39 Building Sino-Japanese Relations Oriented toward the 21st Century by Ma Junwei 47 Comments on Sino-Japanese Relations by Ezra F. Vogel 51 The U.S.-Japan Relationship: a Japanese View by Koji Murata 55 Toward Closer Sino-U.S.-Japan Relations: Steps Needed by Liu Bo 59 The China-Japan-U.S. -

Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks

MM/LD/WG/18/5 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: AUGUST 13, 2020 Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks Eighteenth Session Geneva, October 12 to 16, 2020 STUDY OF THE COST IMPLICATIONS AND TECHNICAL FEASIBILITY OF THE GRADUAL INTRODUCTION OF THE ARABIC, CHINESE AND RUSSIAN LANGUAGES INTO THE MADRID SYSTEM Document prepared by the International Bureau I. INTRODUCTION 1. At its seventeenth session, held in Geneva from July 22 to 26, 2019, the Working Group on the Legal Development of the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks (hereinafter referred to as “the Working Group” and “the Madrid System”) discussed document MM/LD/WG/17/7 Rev. describing possible options for the introduction of new languages into the Madrid System, in particular, Chinese and Russian. The Working Group also discussed document MM/LD/WG/17/10 with a proposal by the Delegations of Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco, Oman, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia on the introduction of Arabic into the Madrid System. 2. The Working Group requested that the International Bureau prepare, for discussion at its eighteenth session, a comprehensive study of the cost implications and technical feasibility (including an assessment of the currently available WIPO tools) of the gradual introduction of the Arabic, Chinese and Russian languages into the Madrid System. 3. As requested by the Working Group, this document discusses the cost implications and technical feasibility of gradually introducing the above-mentioned languages and provides an assessment of the availability of the Madrid System tools in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Spanish and Russian. -

September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia

The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 1 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal: Special Edition Published by the Linguistics Journal Press Linguistics Journal Press A Division of Time Taylor International Ltd Trustnet Chambers P.O. Box 3444 Road Town, Tortola British Virgin Islands http://www.linguistics-journal.com © Linguistics Journal Press 2009 This E-book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the Linguistics Journal Press. No unauthorized photocopying All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Linguistics Journal. [email protected] Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe Senior Associate Editor: Katalin Egri Ku-Mesu Journal Production Editor: Benjamin Schmeiser ISSN 1738-1460 The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 2 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 Table of Contents Foreword by Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe………………………...... 4 - 7 1. Will Baker……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 - 35 -Language, Culture and Identity through English as a Lingua Franca in Asia: Notes from the Field 2. Ruth M.H. Wong …………………………………………………………………………….. 36 - 62 -Identity Change: Overseas Students Returning to Hong Kong 3. Jules Winchester……………………………………..………………………………………… 63 - 81 -The Self Concept, Culture and Cultural Identity: An Examination of the Verbal Expression of the Self Concept in an Intercultural Context 4. -

P. Sercombe Ethno-Linguistic Change Among the Penan of Brunei; Some Initial Observations

P. Sercombe Ethno-linguistic change among the Penan of Brunei; Some initial observations In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 152 (1996), no: 2, Leiden, 257-274 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 05:20:37PM via free access PETER G. SERCOMBE Ethno-Linguistic Change among the Penan of Brunei Some Initial Observations* Introduction Negara Brunei Darussalam (henceforth Brunei) is a small multi-ethnic, multilingual country. The official language is Brunei Malay, and three other dialects of Malay are spoken as well as seven non-Malay isolects (Nothofer 1991:151); among this latter group Iban, Mukah and Penan are considered immigrant to Brunei. The Penan language spoken in Brunei is of the eastern variety1, used by those Penan who occur to the east of the Baram River in Sarawak and within the Kenyah subgroup (Blust 1972:13). Aim This paper aims to examine some non-Penan lexical and discourse features that have been noted in current language use in the Penan language of Brunei (henceforth Sukang Penan), and to compare these with a similar situation in Long Buang Penan in neighbouring Sarawak.2 The main concern here is to show the discrepancy between the position of discrete lexical items and the use of lexis in spontaneous discourse in Sukang. To my knowledge (and Langub's, personal communication) there presently exist no in-depth studies relating to the Penan language varieties of Borneo. To date there have been a number of wordlists published, most * I wish to thank Kelly Donovan for producing the maps and both Peter Martin and Rodney Needham for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. -

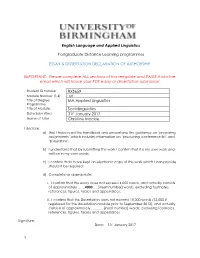

1 English Language and Applied Linguistics Postgraduate Distance Learning Programmes ESSAY & DISSERTATION DECLARATION OF

English Language and Applied Linguistics Postgraduate Distance Learning programmes ESSAY & DISSERTATION DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP IMPORTANT: Please complete ALL sections of this template and PASTE it into the email which will house your PDF essay or dissertation submission Student ID number RXS659 Module Number (1-6) M1 Title of Degree MA Applied Linguistics Programme: Title of Module: Sociolinguistics Date Submitted 31st January 2017 Name of tutor Christine Mackie I declare: a) that I have read the handbook and understand the guidance on ‘preparing assignments’ which includes information on ‘producing a reference list’ and ‘plagiarism’; b) I understand that by submitting this work I confirm that it is my own work and written in my own words; c) I confirm that I have kept an electronic copy of this work which I can provide should it be required; d) Complete as appropriate: i. I confirm that this essay does not exceed 4,000 words, and actually consists of approximately ……4000…. [insert number] words; excluding footnotes, references, figures, tables and appendices; ii. I confirm that this Dissertation does not exceed 15,000 words (12,000 if registered for the dissertation module prior to September 2012), and actually consists of approximately ………. [insert number] words; excluding footnotes, references, figures, tables and appendices. Signature: Date: 31st January 2017 1 The following quotations may be seen as representing a range of opinion in a debate about the role of English as an international language: i) ‘English is neutral’ ...since no cultural requirements are tied to the learning of English, you can learn it and use it without having to subscribe to another set of values […] English is the least localized of all the languages in the world today. -

The Case of Dusun in Brunei Darussalam Hjh. Dyg. Fatimah Binti

3-5 February 2014- Istanbul, Turkey Proceedings of INTCESS14- International Conference on Education and Social Sciences Proceedings 1053 The Vitality & Revitalisation of a Minority Language: The Case of Dusun in Brunei Darussalam Hjh. Dyg. Fatimah binti Hj. Awg. Chuchu (Dr.) & Najib Noorashid Universiti Brunei Darussalam; Brunei Darussalam [email protected]; [email protected]. Keywords: Language vitality, language revitalisation, language extinction, ethnic minority, Dusun, Brunei. Abstract. Language extinction or language death is a sociolinguistic phenomenon which concerns and is often discussed among linguists or members of speaker in general (Aitchison, 2001; Crystal, 2000; Dalby, 2003; Mufwene, 2004; Nelson, 2007; Fishman, 2002; 2007). Due to rapid globalisation, the effect of linguistic "superstratum-substratum" is inevitable (Crystal, 2003), in particular to those languages of ethnic minorities; those in Brunei Darussalam are not the exclusion (Martin, 1995; Noor Azam, 2005; David, Cavallaro & Coluzzi, 2009; Clynes, 2012; Coluzzi, 2012). These minority languages are inclined to endangeredment due to urbanisation, education system, migrations and others, which lead to language shift and consequently, extinction. Brunei Darussalam is a multilingual country that has a diverse population and cultures which generate variations of language and dialect (Nothofer, 1991; Fatimah & Poedjosoedarmo, 1995; Azmi Abdullah, 2001; Jaludin Chuchu, 2005; David, Cavallaro & Coluzzi, 2009). Recognised as one of the seven indigenous in Brunei under the Citizenship Status laws 1961 of the Constitution of Negari Brunei 1959, Dusun ethnic is alleged to have and practice its own code of dialect. All dialects and languages spoken by indigenous ethnics are regarded as minority languages, except for the dialect of Brunei Malay. By focusing on Dusun dialect, this paper discusses the current situation of its language use and perceptions among the native speakers. -

Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities

Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities Summary of a Workshop Discussion Organised by the British Academy in Partnership with the École française d’Extrême-Orient 14 February 2015 Yangon, Myanmar Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 English in Myanmar: a Brief Overview 5 English in Burmese Universities 6 The Experiences of Other Countries 7 Malaysia 7 Thailand 8 Other Countries in Asia and Beyond 8 Observations and Issues for Further Consideration 11 About the British Academy 13 About the École française d’Extrême-Orient 13 2 Language Choice in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities Executive Summary Is English the best medium of instruction for higher education in Myanmar, and, if so, does the solution to current problems in local universities lie in introducing more intensive English-language teaching at the primary and secondary levels? The British Academy and the École française d’Extrême-Orient brought together a group of distinguished experts from Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Australia and the UK, to consider these questions and promote the sharing of lessons among countries in the Southeast Asia region and beyond. This report summarises the outcomes of the discussion and puts forward a number of key messages, with a view to informing the ongoing Myanmar Comprehensive Education Sector Review process: • The best language policy choice for universities in Myanmar may not be either English or Burmese, but some combination of the two. • Language support in Burmese or in English should be extended to students who do not have sufficient language skills to cope adequately with the learning process. • Professional development training for lecturers aimed at improving teaching techniques is needed, including strategies for Burmese and English.