The Natural Vegetation of the Wollongong Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Walks in the Southern Illawarra

the creek and to the lower falls is an easy grade then a steep path takes you to a view of the upper falls. (This sec on was 5 & 6. Barren Grounds Nature Reserve —Illawarra Lookout closed at me of wri ng). It's worth a visit just to enjoy the Adjacent to Budderoo NP, Barren Grounds is one of the few ambience of the rainforest, do some Lyrebird spo ng, check large areas of heathland on the south coast and also has out the visitors’ centre and have a picnic or visit the kiosk. stands of rainforest along the escarpment edge. These varied Park entry fees apply. habitats are home to rare or endangered plants and animals Length: Up to 4km return including the ground parrot, eastern bristlebird and ger Time: Up to 2 hrs plus picnic me quoll. Barren Grounds offers short and long walks on well- formed tracks to great vantage points. The walks are stunning Illawarra Branch| [email protected] Grade: Easy to hard in spring when many of the heath flowers such as boronia, Access: Off Jamberoo Mtn Road, west from Kiama www.npansw.org | Find us on Facebook epacris and, if you’re lucky, waratah, are in full bloom. 3. Macquarie Pass Na onal Park —Cascades 5. Illawarra Lookout 12 Walks in the At the base of the Macquarie Pass and at the edge of the na onal Follow Griffiths Trail from the north-eastern corner of the car park is a deligh ul family friendly walk to a cascading waterfall. park. A er about 1 km walking through forest and heath take Southern Illawarra The parking area is on the northern side of the Illawarra Highway a short path on the le signed to Illawarra Lookout. -

Guide to Cycling in the Illawarra

The Illawarra Bicycle Users Group’s Guide to cycling in the Illawarra Compiled by Werner Steyer First edition September 2006 4th revision August 2011 Copyright Notice: © W. Steyer 2010 You are welcome to reproduce the material that appears in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for personal, in-house or non-commercial use without formal permission or charge. All other rights are reserved. If you wish to reproduce, alter, store or transmit material appearing in the Tour De Illawarra cycling guide for any other purpose, request for formal permission should be directed to W. Steyer 68 Lake Entrance Road Oak Flats NSW 2529 Introduction This cycling ride guide and associated maps have been produced by the Illawarra Bicycle Users Group incorporated (iBUG) to promote cycling in the Illawarra. The ride guides and associated maps are intended to assist cyclists in planning self- guided outings in the Illawarra area. All persons using this guide accept sole responsibility for any losses or injuries uncured as a result of misinterpretations or errors within this guide Cyclist and users of this Guide are responsible for their own actions and no warranty or liability is implied. Should you require any further information, find any errors or have suggestions for additional rides please contact us at www.ibug,org.com Updated ride information is available form the iBUG website at www.ibug.org.au As the conditions may change due to road and cycleway alteration by Councils and the RTA and weather conditions cyclists must be prepared to change their plans and riding style to suit the conditions encountered. -

Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First Submission on Draft Future

Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First Submission on Draft Future Transport Strategy 2056 Illawarra Business Chamber A division of the NSW Business Chamber Level 1, 87-89 Market Street WOLLONGONG NSW 2500 Phone: (02) 4229 4722 SUBMISSION – DRAFT FUTURE TRANSPORT STRATEGY 2056 1. Introduction The Draft Future Transport Strategy 2056 is an update of the NSW Long Term Transport Master Plan. The document provides a 40-year vision for mobility developed with the Greater Sydney Commission, the Department of Planning and Environment and Infrastructure NSW. The Strategy, among other priorities, includes services to regional NSW and Infrastructure Plans aimed at renewing regional connectivity. Regional cities and centres are proposed to increase their roles as hubs for surrounding communities for employment and services such as retail, health, education and cultural activities. 2. Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First The Illawarra Business Chamber (IBC) is the Illawarra Region’s peak business organisation and is dedicated to helping business of all sizes maximise their potential. Through initiatives such as Illawarra First, the IBC is promoting the economic development of the Illawarra through evidence-based policies and targeted advocacy. The IBC appreciates the opportunity to provide a response to the Transport Strategy. 3. Overview of the Illawarra The Illawarra region lies immediately south of the Sydney Metropolitan area, with its economic centre in Wollongong, 85km south of the Sydney CBD. The region extends from Helensburgh in the north to south of Nowra, including the area to the southern boundary of the Shoalhaven local government area (LGA) and the western boundary of the Wingecarribee LGA. The Illawarra region has been growing strongly. -

Moss Vale Newsagency

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS April/May 2020 113 EXPLORER MAP | Southern Highlands THIRLMERE STANWELL TOPS TAHMOOR Blue Mountains WILTON National Park M31 Nattai Lake Cataract National Park BARGO To ydy To Wom ves BULLI Lake Nepean Jellore HILL TOP Joadja Nature HIGH RANGE State Forest Lake Cordeaux Reserve W YERRINBOOL o m b ey a 3 n C 4 a 17 v COLO VALE e s R d 2 WILLOW VALE Lake Avon 5 d R th JOADJA u o Joadja R S d 6 7 d 1 l WELBY O Wonng y C Hw e n e tenn m ia 18 u l H Rd Mang ld O Oxleys Hill Rd d PORT KEMBLA Be im R k K wrr ang a Pa lo BURRADOO ge on id R r d E B d e R Bellanglo r e r l i a Lake Illawarra m V State Forest G a s o R s l o d d d e R South Pacific Ocean n M h V s 16 a a le w CANYONLEIGH p R d I e 15 Molla e warr h Wingecarribee a Highw S ay Reservoir SUTTON FOREST N Rd y ow h w ra ig Illawarra H R e 8 d Canyo nl 10 SHELLHARBOUR AVOCA Rerto Sallys Corner Rd 14 12 BURRAWANG EXETER Minnamurra Rainforest 11 Fitzroy Falls M31 9 Reservoir JAMBEROO 13 undn FITZROY FALLS To bur PENROSE Budderoo National Park KIAMA & Barrengarry WINGELLO Nature Reserve Morton National Park TALLONG Wingello KANGAROO State Forest VALLEY GERRINGONG GERROA BERRY SOUTHERN BOMADERRY | Explorer N © 2019 Base information supplied with permission of the Spatial HIGHLANDS Sevices NSW, 346 Panorama Ave, Bathurst NSW Australia 2795 https://six.nsw.gov.au. -

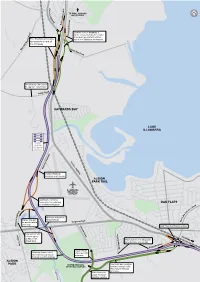

Albion Park Rail Bypass

Cormack Avenue P r i ay n w c r e o TO WOLLONGONG s t o N H AND SYDNEY i M g h s w a e u y nce i n r e P v A k c a m r Cormack Avenue becoming a d Cormack Avenue becoming a o a cul-de-sac and building the second C cul-de-sac and building the second roundaroundaboutbout are are part part of of the the future future FreeFree flowingflowing connectionsconnections planplan ofof the the Tallawarra Tallawarra development development unt Ro o forfor motoristsmotorists on on and and off off M ll the motorway a the motorway h s r a M Yallah Bay Road Wollongong CityCity CouncilCouncil to upgrade Yallah Road Yallah Road HAYWARDS BAY LAKE ILLAWARRA 22 laneslanes eacheach wayway withwith median separationseparation Princes Highway Illawarra Highway IllawarraIllawarra HighwayHighway becomesbecomes a cul-de-saccul-de-sac ALBION PARK RAIL ILLAWARRA REGIONAL AIRPORT SouthboundSouthbound exitexit rampramp travelstravels overover thethe motorwaymotorway OAK FLATS toto thethe IllawarraIllawarra Highway Highway d oa R ce an y tr a n E w h e k g i a L H MotorwayMotorway overpassesoverpasses a w r Tongarra Road RampsRamps maymay not not Tongarra Road e r N a bebe neededneeded until until a Tongarra Road w a l latera later stage stage l Croome Road I Oak Flats Interchange retained CanCan connectconnect withwith aa futurefuture bypassbypass TO KIAMA ofof AlbionAlbion Park Park WoollybuttWoollybutt Drive andand DurgadinDurgadin (Tripoli(Tripoli Way)Way) DriveDrive become aa cul-de-saccul-de-sac Terry Street Terry Durgadin Drive Woollybutt Drive Woollybutt CroomeCroome RoadRoad MotorwayMotorway improvedimproved andand ttravelsravels overover the sshortenedhortened throughthrough Croom Croom motorwaythe motorway RegionalRegional SportingSporting Complex Complex ALBION New local road separates PARK CROOM REGIONAL New local road separates SPORTING COMPLEX llocalocal andand throughthrough traffic. -

190502Rep N113800 Dendrobium Road Transport Assessment

APPENDIX H Road Transport Assessment Dendrobium Mine - Plan for the Future: Coal for Steelmaking Road Transport Assessment Client // Illawarra Coal Holdings Pty Ltd Office // NSW Reference // N113800 Date // 02/05/19 Dendrobium Mine - Plan for the Future: Coal for Steelmaking Road Transport Assessment Issue: B 02/05/19 Client: Illawarra Coal Holdings Pty Ltd Reference: N113800 GTA Consultants Office: NSW Quality Record Issue Date Description Prepared By Checked By Approved By Signed A 21/02/18 Final P Dalton N Vukic N Vukic Nicole Vukic Final – Additional P Dalton N Vukic B 02/05/19 K McNatty Analysis A Modessa K McNatty © GTA Consultants (NSW) Pty Ltd [ABN 31 131 369 376] 2019 The information contained in this document is confidential and intended solely for the use of the client for the purpose for which it has been prepared and no representation is made or is to be implied as being made to any third party. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of GTA Consultants Melbourne | Sydney | Brisbane constitutes an infringement of copyright. The intellectual property contained in this document remains the property of GTA Consultants. Adelaide | Perth Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Existing Mine Operations 3 2.1 Dendrobium Mine 3 2.2 Road Transport Aspects of Existing Operations 4 2.3 Dendrobium Pit Top 8 2.4 Kemira Valley Coal Loading Facility 10 2.5 Cordeaux Pit Top 10 2.6 Dendrobium CPP 10 2.7 Dendrobium Shaft Numbers 1, 2 and 3 10 3. Project Description 11 4. -

Walks, Paddles and Bike Rides in the Illawarra and Environs

WALKS, PADDLES AND BIKE RIDES IN THE ILLAWARRA AND ENVIRONS Mt Carrialoo (Photo by P. Bique) December 2012 CONTENTS Activity Area Page Walks Wollongong and Illawarra Escarpment …………………………………… 5 Macquarie Pass National Park ……………………………………………. 9 Barren Grounds, Budderoo Plateau, Carrington Falls ………………….. 9 Shoalhaven Area…..……………………………………………………….. 9 Bungonia National Park …………………………………………………….. 10 Morton National Park ……………………………………………………….. 11 Budawang National Park …………………………………………………… 12 Royal National Park ………………………………………………………… 12 Heathcote National Park …………………………………………………… 15 Southern Highlands …………………………………………………………. 16 Blue Mountains ……………………………………………………………… 17 Sydney and Campbelltown ………………………………………………… 18 Paddles …………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Bike Rides …………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Note This booklet is a compilation of walks, paddles, bike rides and holidays organised by the WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club over the last several years. The activities are only briefly described. More detailed information can be sourced through the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, various Councils, books, pamphlets, maps and the Internet. WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club 2 October 2012 WEA ILLAWARRA RAMBLERS CLUB Summary of Information for Members (For a complete copy of the “Information for Members” booklet, please contact the Secretary ) Participation in Activities If you wish to participate in an activity indicated as “Registration Essential”, contact the leader at least two days prior. If you find that you are unable to attend please advise the leader immediately as another member may be able to take your place. Before inviting a friend to accompany you, you must obtain the leader’s permission. Arrive at the meeting place at least 10 minutes before the starting time so that you can sign the Activity Register and be advised of any special instructions, hazards or difficulties. Leaders will not delay the start for latecomers. -

Danny Scott 1215 Points Hurry to Fly Early

MARCH 1984 Publication N°. NBH 1436 CONTENTS SKYSAILOR IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE HANG GLIDING FEDERATION OF AUSTRALIA (H .G. F. A. ) Skysai l or appears twelve times a year and is provid ed as a service to members . For non -members , the sub How yo goin I folks? 3 scription rate is $20 per annum . Cheques should be Portland 1984 made payable and sent to HGFA . 6 The Lawrence Hargrave Interna International 1984 10 The First Thermal 14 Skysai lor is published to create further interest in the sport of hang gliding . Its primary purpose is to The Day Bakewell Boomed 18 provide a ready means of commu nication between hang Australian X -C League - report 19 g l ~ding enthusiasts in Australia and in this way to, Taking Off . 20 advance the future development of the sport and its Widgee Mountain Invitational 22 methods of safety. Unreal - Oh Shit! 24 Qld News 25 Contributions are welcomed . Anyone is invited to Letters to the Editor 26 contribute articles , photographs and illustrations Market Place 26 concerning hang gliding activities . The Editor reserves the right to edit contributions where necc Typing - Barb Aitken essary. HGFA and the Editor do not assume responsib ility for the material or the opinions of contribut Layout - Gavin H'll and John Murby ors presented in Skysailor. Copyright in Skysai lor is vested in the HGFA . Copy right in articles is vested in each of the authors in respect of her or his contribution. Deadline for For information about ratings or sites write to contributions : 1st of the month . -

Slag Products Contributing to the Sustainability of the World Blast Furnace Slag Cement Potential to Save 64.5 MT of CO2 Emissions Annually

ASANews Aug 05 4pp 19/8/05 1:07 PM Page 1 newsbriefs Vol 3 | Issue 5 | Aug 2005 05 QUARTERLY ASMS: Robert Cignarella Commenced work Richard has dust and wet sludge from the Sinter Plant, with ASMS on July 13 2005, in the role of contributed rendering them non hazardous for disposal. ASSOCIATION Product Manager for Concrete Aggregates, and enormously to the will also further develop new markets for the development of slag Ecocem product. products into the He has many years’ experience in ready market, particularly in c nnections mixed concrete with both Boral and Metromix, civil and roadbase and more recently has applications. australasian slag (iron & steel) association newsletter www.asa-inc.org.au been working in a He left ASMS to pursue some new challenges < from page 1: Blast Furnace sales function at in the Western Sydney area. The Australasian emissions would be avoided. Also the mining of Cement Australia. He (iron and steel) Slag Association members wish raw materials like limestone, clay or sand would Slag products contributing to is familiar with not only Richard all the best in his future endeavours and be decreased by more than 100 Mt annually. all the ASMS products, thank him for his contribution to the work of the In using GGBS there is the initial reduction of but also their customer Association. energy costs, added to this is the technical the sustainability of the world base. advantages of slag cements. The use of GGBS Robert is married to Marie, and has two Seminar Papers Available – Papers from the is a well-established method to realise a real For much of the 20th Century the mineral and Today’s needs should not comprise the ability References: 1. -

Macquarie Pass National Park – Established in 1969 – Illawarra Subtropical Rainforest

T N ARPM E SC E A R Macquarie Hill R Macquarie PassA National Park W A L IL NSW National Park v v v v v vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv Main Roads v v vvvvvvvvvvvvv v v v v Sealed roads Mc v v v v G Fire trails u i No Wood Dogs not No n v v e ad s v v vRo v Fires permitted camping Walking tracks s v v v v v y a v rr D u M M Power lines r a i v t c q e n u u v v v o a Railway line M r v v v v v v v v ie v v v v P vvvvvvvvvvvvvvv v Glenview a v v v v v v s Waterfalls v v s warra vvvvvvvvvvvvvv v / Illa H v v v v v v i v g G vvvvvvvvvvvvvv MACQUARIE PASS h l v v v v v To Robertson w e n a Bird watching v v v v y ie w v NATIONAL PARK F ir Information Clover Hill et ra Carpark il FORD Parking l Picnic Tables ai tr ire F ill C H asc er ade ov s Cl W Clover a Hill Cascade lk Falls Cascade Falls YOU ARE Carpark & HERE Picnic Area uarie cq a Ri Rainbow M vu le Falls tt To Wollongong ra Min gar e Road N Ton IL L A W A R R A E 0 1km k SC arra Cree ane A ng L RP o ra M T ar EN ng T To Macquarie Pass National Park – established in 1969 – Illawarra SubTropical Rainforest. -

Southern Highlands June

JUNE - JULY SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS FREE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER REAL ESTATE OPEN HOMES HIGHLANDS HOUND WHAT’S ON DIGITAL PL_SH_001.indd 1 24/6/21 10:47 am Property Highlight STONE SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS 1 67 Sir James Fairfax Circuit, Bowral Price Guide: $2,550,000 Timeless and Indulgent Living Located in Bowral’s exclusive Retford Park Estate, expansive of entertaining. Four impressive bedrooms and a separate media “Meticulous in its design and living, deluxe finishes and superb entertaining eortlessly room completes the more than ample interior accommodation, impeccable in its presentation, this converge to deliver a flawless home that embraces impeccable while three sumptuous bathrooms and powder room all with stunning home delivers an unforgettable design and meticulous attention to detail. underfloor heating add an extra touch of glam. rst impression. Showcased by a grand Built just over a year ago and placed on a wonderfully easy-care A secure extra-large double garage oers internal access as 1005sqm land parcel, the lifestyle and prestige that this home well as shelving and a storage room, and a 14kw inverter entry hallway, it spoils you with space, oers presents, secures it as an irresistible prospect for the luxury ducted reverse cycle air conditioning system ensures privacy and a never-ending rural buyer. Understated sophistication radiates throughout, with a year-round comfort. panorama that stretches across green generous floor plan providing remarkable accommodation for Bi-fold stacker doors allow an uninterrupted flow from the pastures to the rolling hills beyond.” families and guests alike. living area to the alfresco terrace, where you will spend many The sizeable open plan living area, complete with statement memorable occasions hosting guests while savouring the wood fire, evokes a gorgeous country ambience that perfectly picture-perfect views. -

Reminiscences of Illawarra by Alexander Stewart

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1987 Reminiscences of Illawarra by Alexander Stewart Michael K. Organ University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Organ, Michael K.: Reminiscences of Illawarra by Alexander Stewart 1987. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/149 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Reminiscences of Illawarra by Alexander Stewart Abstract The following "Reminiscences of Illawarra" initially appeared in the Illawarra Mercury between 17 April and 18 August 1894 in 24 parts, each part usually dealing with a separate aspect of the very early history of Illawarra, and more specifically with the early development of the township of Wollongong.This book is one of a continuing series to be published as aids to the study of local history in Illawarra. Some thirty works are at present in preparation or in contemplation. The series' objective is to provide low-cost authentic source material for students as well as general readers. Some of the texts will be from unpublished manuscripts, others from already published books which however are expensive, rare, or not easily obtainable for reference. They may well vary in importance, although all will represent a point of view. Each will be set in context by an introduction, but will contain minimal textual editing directed only towards ensuring readability and maximum utility consistently with complete authenticity.