Oral History Interview with Nan Goldin, 2017 April 30-May 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Tourism Guide

Your Guide to Charm City’s Best Restaurants and Attractions Baltimore, Maryland January 4-8, 2012 Welcome to Baltimore,Hons! Inside this Guide: This Guide will provide you with all the information you need to make your interlude in Baltimore (Balmer, as the locals say) pleasant and enjoyable. Rick n’ Nic have done all Bars & Restaurants 2-3 the hard work to find the best spots for dining, libations, and local attractions. (No, Attractions 4-5 Rick n’ Nic are not local attractions). For many months, we have selflessly labored to Local Necessities 6-7 sample all that Baltimore has to offer — this Guide provides the result of our exten- Cruising Around 8 sive scientific research. We list our favorite restaurants, pubs, and attractions, to- gether with helpful maps to make sure that you don’t lose your way while exploring our fine city. Also look for the discounts! We also listed local pharmacies, banks, parking and other important locations in the vicinity. On the final page, we include information on how to get around town (and even how to reach DC) during your con- ference stay. Hope you enjoy your visit to the Land of Pleasant Living, Hons! How to Speak Balmerese: Chest Peak - Chesapeake The kitschy Hon tradition began between the 1950s and 1970s. It was common to see Wooder - What’s in the Chest working class women from the Hampden, Highlandtown, and Canton neighborhoods Peak. wearing gaudy bright dresses with outdated glasses and beehive hairdos. Men often Merlin - The state you’re in! dressed casually as many of them worked at the local factories and docks. -

FREDDY CORBIN Oakland Tattoo Artist

FREDDY CORBIN Oakland tattoo artist. Shot for Inked Magazine. REFUELEDMAGAZINE.COM LIFESTYLE INTERVIEW BY JAMIE WATSON PHOTOGRAPHS BY JAY WATSON California photographer Jay Watson specializes in lifestyle and environmental portraits of people on location. His work involves shooting for editorial, advertising, clothing, music, entertainment, industrial, and corporate clients. Elemental Magazine once wrote “he shoots the crazy shit,” and an early issue of Garage Magazine said “Jay came to California to raise free range artichokes.” Some of these things are true. You were raised in Baltimore, Maryland. What did you bring to What was the first thing you photographed when you arrived to California’s table? California in 1999? I brought a plastic toy camera, a humidor filled with some cigars, 6 The "Welcome to California" sign. I pulled over right after the border bungee cords, an Alpine car stereo, and a Biz Markie CD. It was all inspectors check incoming vehicles carrying fruit and vegetables. I stolen the first week I moved to the Bay Area along with shot the sign with a Polaroid Land camera. Then I got distracted in some other stuff. I guess it was a toll I had to pay, but nobody told me Joshua Tree and stayed there an extra day to shoot and drink up about it before I got here. They let me keep my Baltimore accent and the California desert. I also hit the Dinosaurs at Cabazon with the blue collar work ethic. I'll never shake those things. In toy camera. reality I came with a desire to just find my own way, but now I feel the ability to contribute. -

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

THE FOSSIL Official Publication of the Fossils, Inc., Historians of Amateur Journalism Volume 105, Number 1, Whole Number 338, G

THE FOSSIL Official Publication of The Fossils, Inc., Historians of Amateur Journalism Volume 105, Number 1, Whole Number 338, Glenview, Illinois, October 2008 A HISTORIC MOMENT President's Report Guy Miller Yes, a historic moment it is. Our first election under our new set of by-laws has been successfully conducted and the officers have taken their places. As outlined, the election was for three members to compose the Board of Trustees. All other offices have become appointive. In addition, the position of Vice-President has been eliminated. All officers will serve for a two-year term. In 2010 only two positions on the Board will be open: the incumbent President will remain as carry over but will relinquish his title, and the new Board will proceed to choose one among them once more for President for 2010-12. That's the “game plan,” so to speak. On August 4, Secretary-Treasurer Tom Parson delivered to the President the results of the election: Number of ballots received = 21 Louise Lincoln 1 Danny L. McDaniel 8 Guy Miller 18: Elected Stan Oliner 18: Elected Jack Swenson 17: Elected Immediately upon receipt of the report, I called upon the newly elected members to give to the Secretary-Treasurer their choices for the new President to serve for the 2-year term 2008-2010. Their choice was that I should be that person. And so, I begin another stint at the end of which I will have had a ten-year try plus an earlier term (1994-95). Hopefully, by 2010 all of you will have had enough of me and, mercifully, put me out to pasture! In the meantime, I am very pleased to tell you that everyone I have asked has agreed to work along with the Board for the next two years: Ken Faig, Jr. -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge Author Affiliation Paul R. Abramson & University of California, Tania L. Abramson Los Angeles Abstract: Learning that an artist was a victim of inconceivable torment is critical to how their artworks are experienced. Forced as it were to absorb the wretched demons from the here and now, artists such as David Wojnarowicz have implau- sibly found the resolve to depict this adversity, and its psychological detritus, in their singularly creative manners. Recognised for his autobiographical writings no less than his artwork, Wojnarowicz is especially admired for his sheer defiance of conventional life scripts, and his fortitude in the face of adversity in the circum- scribed world of imaginative constructions. Arthur Rimbaud in New York, A Fire in My Belly, and Wind (for Peter Hujar) for example. The enduring value of his artwork, inextricably enhanced by his diaries and essays, is that they simultane- ously provide a narrative portal into the untangling of his inner life, as well as fundamentally influence how these works are perceived. When looking at two paintings, ostensibly by Rembrandt, is there an aesthetic difference in how these paintings are experienced if we know that one of the two paintings is a forgery? Most certainly, declared Nelson Goodman, who noted that this bit of knowledge ‘makes the consequent demands that modify and differentiate my present experience in looking at the two [Rembrandt] paintings’.1 Is that also true about depictions of Christ on the cross? Does knowledge of Christ’s story alter how Michelangelo’s Christ on the Cross is experienced? If what we know, or think we know, has the capacity to ultimately influence © Aesthetic Investigations Vol 3, No 1 (2020), 146-157 Paul R. -

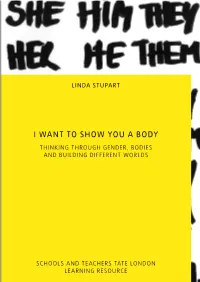

I Want to Show You a Body Thinking Through Gender, Bodies and Building Different Worlds

LINDA STUPART I WANT TO SHOW YOU A BODY THINKING THROUGH GENDER, BODIES AND BUILDING DIFFERENT WORLDS SCHOOLS AND TEACHERS TATE LONDON LEARNING RESOURCE INTRODUCTION Growing up as a gender non-conforming adults) we learn that 53% of respondents child, it was art and being in the art room had self-harmed at some point, of which that was my safe haven. Like other gender 31% had self-harmed weekly and 23% daily. and sexually diverse people, such as lesbian, These and other surveys show that many gay, bisexual and queer people, trans and trans people experience mental distress, gender-questioning people can be made and we know that there is a direct correlation to feel ashamed of who we are, and we between this and our experiences of have to become more resilient to prejudice discrimination and poor understandings in society. Art can help with this. There is of gender diversity. As trans people, we no right and wrong when it comes to art. need to be able to develop resilience and There’s space to experiment. to manage the setbacks that we might Art is where I found my politics; where experience. We need safe spaces to explore I became a feminist. Doing art and learning our feelings about our gender. about art was where I knew that there was Over recent years at Gendered Intelligence another world out there; a more liberal one; we have delivered a range of art-making more radical perhaps; it offered me hope projects for young trans and gender- of a world where I would belong. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

Brenna's Story

ccanewsletter of the children’s craniofacialnetwork association Cher — honorary chairperson summer 2005 inside cca teen brittany stevens. 2 cca grad tiffany kerchner. 3 cca supersib message lauren trevino . 4 from the chairman 2005 retreat recap . 5-7 Brenna Johnston n the spring issue of the fundraising news. 8 inewsletter Tim Ayers brenna’s story announced that he was cca programs . 11 by Robyn Johnston stepping down as calendar of events. 11 Chairman of the CCA Board of Directors. He has early a decade ago, my husband Erin and I discovered provided countless hours of prosthetic ears . 12 nwe would soon be parents. Like all parents, we his personal time to our wanted to raise a child that was happy, healthy and well mission and we will miss nacc recap . 13 adjusted. On May 14, 1996, Brenna, the first of our three him as Chairman. children, entered the world. She instantly was my little Tim is not going far as he 3 cheers . 14 Sugarplum, such a sweet baby! will still be on the Board of Her journey has not been easy, but you would never Directors. He is especially pete’s scramble . 16 know it meeting her today. She knows that she’s a typical committed to leading our kid who just happens to have been born with head and advocacy efforts to get facial bones too small to function properly, and we try to health insurance companies 2006 Retreat Info keep her life as balanced as possible. Here’s the typical to cover craniofacial part: Her favorite food is catsup, with hotdogs and ham- The 16th Annual Cher’s surgeries that today are burgers, no buns. -

NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019 – 11 January 2020 Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce its first exhibition with Nan Goldin, who joined the gallery in September 2018. This major exhibition – the first solo presentation by the artist in London since the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002 – presents an important range of historical works together with three new video works exhibited for the first time. Over the past year Goldin has been working on a significant new digital slideshow titled Memory Lost (2019), recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction. This captivating, beautiful and haunting journey unfolds through an assemblage of intimate and personal imagery to offer a poignant reflection on memory and the darkness of addiction. It is one of the most moving, personal and visually arresting narratives of Goldin’s career to date, and is accompanied by an emotionally charged new score commissioned from composer and instrumentalist Mica Levi. Documenting a life at once familiar yet reframed, new archival imagery is cast to portray memory as lived and witnessed experience, yet altered and lost through the effects of drugs. Bearing thematic connections to Memory Lost, another new video work, Sirens (2019), is presented in the same space. This is the first work by Goldin exclusively made from found video footage and is also accompanied by a new score by Mica Levi. Echoing the enchanting call of the Sirens from Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores, this hypnotic work visually and acoustically entrances the viewer into the experience of being high.