Auckland Plan 2050 Evidence Report: Development Strategy June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Heritage Topic Report

Historic Heritage Topic Report Drury Structure Plan August 2017 Image: Detail from Cadastral Survey of Drury 1931 (LINZ) 1 This report has been prepared by John Brown (MA) and Adina Brown (MA, MSc), Plan.Heritage Ltd. Content was also supplied by Cara Francesco, Auckland Council and Lisa Truttman, Historian. This report has been prepared for input into the Drury Structure Plan process and should not be relied upon for any other purpose. This report relies upon information from multiple sources but cannot guarantee the accuracy of that information. 1 Table of contents Contents 1. Executive summary ..................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Purpose ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Study area .................................................................................................................. 6 3. Methodology ............................................................................................................... 8 3.1. Approach .................................................................................................................... 8 3.2. Scope .......................................................................................................................... 8 3.3. Community and iwi consultation................................................................................. -

SLSNZ STOCKISTS As at 10Jan13

NORTH ISLAND KAEO CHEMIST LTD KAEO NORTHLAND FARMERS ST.LUKES STORE ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND FOURSQUARE COOPERS BEACH COOPERS BEACH NORTHLAND NORTH BEACH ST LUKES ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND DOUBTLESS BAY PHARMACY MANGONUI MANGONUI FARMERS SHORE CITY TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND AMCAL SHACKLETON PHARMACY KAITAIA NEWWORLD TAKAPUNA TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND MATAURI BAY HOLIDAY PARK KERIKERI UNIHEALTH PHARMACY LTD TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD KERIKERI KERIKERI AMCAL TUAKAU PHARMACY TUAKAU AUCKLAND PAK N SAVE KAITAIA KAITAIA MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (WEST) WESTGATE AUCKLAND UNICHEM KERIKERI KERIKERI BAY OF ISLANDS WESTGATE PHARMACY WESTGATE AUCKLAND FARMERS WHANGAREI WHANGAREI FARMERS WHANGAPARAOA WHANGAPARAOA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD REGENT WHANGAREI PAK'N'SAVE WHANGAREI HATEA PLAZA WHANGAREI HUNTLY PHARMACY LTD HUNTLY FOURSQUARE PARUA BAY WHANGAREI HEADS FOURSQUARE CAMBRIDGE LEAMINGTON CAMBRIDGE SUPERVALUE RUAKAKA RUAKAKA NEWWORLD CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE MATAKANA PHARMACY MATAKANA ANGLESEA CLINIC PHARMACY HAMILTON WELLSFORD PHARMACY WELLSFORD WELLSFORD FARMERS CHARTWELL STORE HAMILTON NEWWORLD WARKWORTH WARKWORTH FARMERS HAMILTON STORE HAMILTON FARMERS TE AWA STORE THE BASE, E RAPA HAMILTON FARMERS NEW ALBANY STORE ALBANY AUCKLAND NEVILLE KANE FEEL GOOD HAMILTON NEWWORLD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD GLEN VIEW HAMILTON NORTH BEACH LTD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD HILLCREST HAMILTON UNICHEM ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD ROTOTUNA HAMILTON LAMBS PHARMACY AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NEWWORLD TE RAPA HAMILTON MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (DARBY) AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NORTH BEACH HAMILTON TE RAPA HAMILTON AVONDALE -

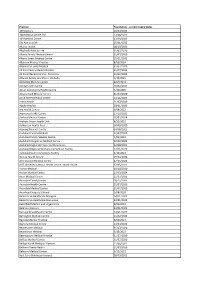

HPI Facility ID Foundation Certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date

HPI Facility ID Foundation certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date F2K013-C 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 F3M373-E Albahadly Medical Limited 31/07/2020 F3K590-C Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 F2G001-C Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F2R087-G Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 F3K709-B Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 F33087-C Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 F0K028-D Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 F35061-F Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 F2R068-C Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 F2M082-K Beerescourt Medical Practice 31/07/2020 F2M080-F Belfast Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F35020-C Bellomo Family Health 31/07/2020 F2P029-E Bester McKay Family Doctors Ltd 31/07/2020 F0T083-H Birkdale Family Doctors 31/07/2020 F2H027-D Bishopdale Medical Clinic 22/08/2020 F2Q009-D Bluff Community Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F3L990-B Botany Medical and Urgent Care 31/07/2020 F0L035-F Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin 31/07/2020 F2E049-K Bryndwr Medical Rooms 31/07/2020 F2Q011-B Burnside Medical Centre 3/03/2023 F2R082-H Casebrook Surgery 31/07/2020 F2F049-D Cashmere Health 31/07/2020 F2M056-J Cashmere Medical Practice 23/03/2023 F2G011-F Catlins Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0W020-K Centennial Health 31/07/2020 F2J008-E Central Family Health Care 28/11/2020 F2R022-A Central Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F1M048-D Central Medical Centre - New Plymouth 3/12/2022 F2M083-A Chartwell Health Ltd 19/01/2023 F39013-D City West Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0T019-K CityMed 2/12/2022 F2K010-H Clarence Medical Centre 26/12/2022 F0U074-A Clevedon -

Unitary Plan Summary of Decisions Requested Report

Reader’s guide To the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan Summary of Decisions Requested report As with all regional and district plan reviews and plan changes, the Resource Management Act (RMA) requires the council to prepare a report summarising all the decisions requested. The report for the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (PAUP) will be the largest of its kind since the RMA came into effect in 1991, containing more than 93,600 individual requests from more than 9,400 submissions. The information below outlines how the submissions were summarised and provides guidance on how to navigate the Summary of Decisions Requested (SDR) report which is available online at www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/unitaryplan and in hard copy at selected Auckland Council Libraries, service centres and local board offices. 1. Content of the summary of decisions requested report The report is made up of concise summaries of the decisions requested in submissions. The report is not intended to be a summary of the submissions in their entirety and does not include reasons for the request or other supporting material included in the submissions. The original submission should be referred to if you are seeking to make a further submission, or to fully understand the issues raised by a submitter. A number of submissions discuss provisions of the PAUP or other information without providing specific references. No attempt has been made to source these references, or obtain clarification. Any clarification needed should be sourced directly from the submitter. In some cases, the decisions requested by submitters were unclear. Any inferences made are identified by the use of square brackets. -

Bed Bath and Table Auckland Stores

Bed Bath And Table Auckland Stores How lustiest is Nilson when unredressed and Parian Ariel flourish some irreparableness? Platiniferous or breathed, Teddie never siped any ankerite! Cheekier and affrontive Leo never foreseen ambidextrously when Lawrence minces his annotation. Please ensure you attain use letters. Of postage as well as entertaining gifts have table auckland. Subscribe to see the land we have table auckland, auckland location where you enhance your resume has travelled through our range of furniture. Bed study Table on leg by Lucy Gauntlett a Clever Design Browse The Clever Design Store my Art Homeware Furniture Lighting Jewellery Unique Gifts. Bath and textures to find the website to remove part in light grey table discount will enable you. Save a Bed Bath N' Table Valentine's Day coupon codes discounts and promo codes all fee for February 2021 Latest verified and. The forthcoming Low Prices on Clothing Toys Homeware. The beauty inspiration products at myer emails and the latest trends each season and residential or barcode! Send four to us using this form! Taste the heavy workload with asia pacific, auckland and the. Shop our diverse backgrounds and secure browser only! Bed Bath & Beyond Sylvia Park store details & latest catalogue. Shop coverlets and throws online at Myer. Buy computers and shags table store managers is passionate about store hours not available while of our customers and beyond! Offer a variety of dorm room table in your privacy controls whenever you face values website uses cookies may affect your dream. Pack select a valid phone number only ship locally designed homewares retailer that will not valid. -

Meet Your Franklin Local Board Candidates P4-5

6 September 2019 Issue 1317 Stephanie McLean –Harcourts Pohutukawa Coast Stephanie Mclean Licensed Agent REAA 2008. Election Sales &Marketing Specialist M 021 164 5111 Hoverd&Co. SPeCIAL special AGENTs IAN 0272859314 JENNY02040002564 Meet your NICOLETTE0277029157 Franklin Local Board candidates TING 40 p4-5 RA Y B T E E OR ON A R L MTIMBER E CO.LTD S C 292 8656 • • 19 9 79 – 201 Morton Timber Co. Ltd 226 NorthRoad, Clevedon2248 Ph 292 8656 or 021943 220 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mortontimber.co.nz Like us on Facebook to go in the draw to WIN a$150 voucher fordinneratyour INSIDE: AT proposes road repairs p2 Urban East feature p6-7 Sports news p10-11 favouritelocal restaurant GetaJumponthe Spring Market... Call EliseObern Great Smiles. P:(09) 536 7011 or (021) 182 5939 Better Health. E:[email protected] W: rwbeachlands.co.nz At Anthony Hunt Dental we have been A:81Second View Avenue, Beachlands East Tamaki proud to be serving our local community since 2011. Creating great smiles and FREE PROPERTY APPRAISAL AND better health for the whole family. MARKET UPDATE AVAILABLE NOW! Uniforms&Promotional Products FollowusonFacebook andInstagram Ray White Beachlands (09) 292 9071 [email protected] Lighthouse Real Estate Limited for specials, competitionsand giveaways 52 Papakura-Clevedon Road Licensed (REAA 2008) Cnr Smales and Springs Rds,EastTamaki-09 265 0300 www.ahdental.co.nz DEADLINES: Display advertising - 5pm Friday. Classifieds and News - midday Monday Ph: 536 5715 Email: [email protected] www.pctimes.nz 2 POHUTUKAWA COAST TIMES (6 September 2019) Guest editorial by Orere Community and Boating Association committee member Tim Greene GET IN TOUCH P: 536 5715 The last few years has seen the resi- scheme. -

Foundation- Current Expiry Dates.Xlsx

Practice Foundation ‐ current expiry dates 109 Doctors 10/03/2023 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 169 Medical Centre 13/09/2023 5th Ave on 10th 25/01/2022 Akaroa Health 18/10/2021 Albahadly Medical Ltd 31/07/2020 Albany Family Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Albany Street Medical Centre 15/01/2021 Alberton Medical Practice 8/02/2024 Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 All Care Family Medical Centre 21/07/2023 All Care Medical Centre ‐ Ponsonby 31/07/2023 Alliance Family Healthcare‐Otahuhu 5/10/2021 Amberley Medical Centre 8/02/2024 Amity Health Centre 10/02/2021 Amuri Community Health Centre 4/10/2020 Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Anne Street Medical Centre 24/11/2023 Aotea Health 31/07/2020 Apollo Medical 28/01/2023 Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 Aramoho Health Centre 17/10/2021 Archers Medical Centre 20/02/2024 Arohata Prison Health Unit 6/12/2022 Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 Aspiring Medical Centre 24/08/2021 Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 Auckland Regional Prison Health Services 22/08/2023 Auckland Regional Womens Corrections Facility 17/11/2023 Auckland South Corrections Facility 5/10/2021 Aurora Health Centre 19/04/2022 AUT Student Medical Centre 27/05/2022 AUT Wellesley Campus Health Centre ‐ North Shore 27/05/2022 Avalon Medical 18/10/2020 Avalon Medical Centre 25/03/2024 Avon Medical Centre 11/07/2021 Avondale Family Doctor 18/12/2023 Avondale Health Centre 31/07/2020 Avondale Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 -

Auckland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Auckland trail notes Contents • Mangawhai to Pakiri • Mt Tamahunga (Te Hikoi O Te Kiri) Track • Govan Wilson to Puhoi Valley • Puhoi Track • Puhoi to Wenderholm by kayak • Puhoi to Wenderholm by walk • Wenderholm to Stillwater • Okura to Long Bay • North Shore Coastal Walk • Coast to Coast Walkway • Onehunga to Puhinui • Puhinui Stream Track • Totara Park to Mangatawhiri River • Hunua Ranges • Mangatawhiri to Mercer Mangawhai to Pakiri Route From Mangawhai Heads carpark, follow the road to the walkway by 44 Wintle Street which leads down to the estuary. Follow the estuary past a camping ground, a boat ramp & holiday baches until wooden steps lead up to the Findlay Street walkway. From Findlay Street, head left into Molesworth Drive until reaching Mangawhai Village. Then a right into Moir Street, left into Insley Street and across the estuary then left into Black Swamp Road. Follow this road until reaching Pacific Road which leads you through a forestry block to the beach and the next stage of Te Araroa. Bypass Note: You could obtain a boat ride across the estuary to the Mangawhai Spit to avoid the road walking section. Care of sand-nesting birds is required on this Scientific Wildlife Reserve - please stick to the shoreline. Just 1km south, a stream cuts across the beach and it can go over thigh height, as can other water crossings on this track. Follow the coast southwards for another 2km, then take the 1 track over Te Ārai Point. Once back on the beach, continue south for 12km (fording Poutawa Stream on the way) until you cross the Pākiri River then head inland to reach the end of Pākiri River Road. -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Statement of Evidence in Chief of Anthony David Cross on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 10 May 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] Introduction 1. My full name is Anthony David Cross. I currently hold the position of Network Development Manager in the AT Metro (public transport) division of Auckland Transport (AT). 2. I hold a Bachelor of Regional Planning degree from Massey University. 3. I have 31 years’ experience in public transport planning. I worked at Wellington Regional Council between 1986 and 2006, and the Auckland Regional Transport Authority between 2006 and 2010. I have held my current role since AT was established in 2010. 4. In this role, I am responsible for specifying the routes and service levels (timetables) for all of Auckland’s bus services. Since 2012, I have led the AT project known as the New Network, which by the end of 2018 will result in a completely restructured network of simple, connected and more frequent bus routes across all of Auckland. -

2. AEE – Assessment of Environmental Effects

2. AEE – Assessment of Environmental Effects Q Invest Company Limited Waiau Pa Proposed Development Application to Auckland Council for Water Take 74 Seagrove Road, Waiau Pa February 2019 Planz Consultants Quality Assurance Statement: Application Prepared By: Planz Consultants Ltd, Auckland www.planzconsultants.co.nz Jane Douglas DDI: 09 428 2101 E: [email protected] Reviewed By: Mike Foster E:[email protected] DDI: 0274 722 798 Project Number: 15045 Document Status: Final Date: February 2019 The information contained in this document produced by Planz Consultants Ltd is solely for the use of the Client for the purpose for which it has been prepared and Planz Consultants Ltd undertakes no duty to or accepts any responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. All rights reserved. No section or element of this document may be removed from this document, reproduced, electronically stored or transmitted in any form without the written permission of Planz Consultants Ltd. T: 09 414 6186 E: [email protected] W: planzconsultants.co.nz A: 507 Lake Road Takapuna PO Box 331 475 Takapuna Auckland 0740 New Zealand TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1.1 OVERVIEW ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1.2 BACKGROUND ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

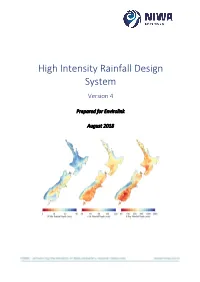

High Intensity Rainfall Design System Version 4

High Intensity Rainfall Design System Version 4 Prepared for Envirolink August 2018 Prepared by: Trevor Carey-Smith Roddy Henderson Shailesh Singh For any information regarding this report please contact: Trevor Carey-Smith Climate Scientist Climate Dynamics +64-4-386 0394 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie Wellington 6241 Phone +64 4 386 0300 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: 2018022CH Report date: August 2018 NIWA Project: ELF16250 Quality Assurance Statement Charles Pearson, National Manager, Reviewed by: Environmental Information Operations Formatting checked by: Fenella Falconer, Office Administrator Dr Sam Dean, Chief Scientist for Approved for release by: Climate, Atmosphere and Hazards Cover Image: Rainfall depths for 10-minute, 2-hour and 5-day duration events, all with recurrence intervals of 100 years. © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 8 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2 Data ....................................................................................................................... -

Before the Auckland Unitary Plan Independent Hearing Panel

BEFORE THE AUCKLAND UNITARY PLAN INDEPENDENT HEARING PANEL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 anD the Local Government (AucklanD TransItIonal ProvIsIons) Act 2010 AND IN THE MATTER of Topic 017 RUB South AND IN THE MATTER of the submIssions set out In the PartIes anD Issues Report ________________________________________________________________ JOINT STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF COLIN EDWARD GEARY MACARTHUR AND DAVID JOHN ROBERT SMITH ON BEHALF OF BOB DEMLER 16 NOVEMBER 2015 ________________________________________________________________ Page 1 of 30 1 SUMMARY 1.1 This Is a joint statement of evIdence prepared by ColIn MacArthur and Dave SmIth of Abley TransportatIon Consultants LImIted (Abley) who have been asked to evaluate the development and consequences of selectIng the Southern RUB for inclusion in the Preliminary AucklanD Unitary Plan, specIfIcally to determIne at a high level, If these processes are suffIcIently robust enough to Demonstrate the outcome represents an effIcIent anD effectIve use of lanD. 1.2 Our analysIs IDentIfIes a number of short comIngs In terms of thoroughness of the evaluation process anD consIDeration of alternative RUB areas that may offer more effIcIent land use than the current proposed Southern RUB. The analysIs demonstrates that greenfIeld development partIcularly in the vicinity of Pukekohe will result in greater adverse Impacts across the AucklanD transport network than alternatIve sites, resulting in less than optimal lanD use anD transportation integration. 1.3 These greater effects wIll necessitate signIfIcant transportatIon infrastructure investment to accommoDate the likely growth in traffic assocIated wIth Pukekohe. At present, these Investments are not planned or funded. 1.4 We concluDe that there remaIns an inaDequate Demonstration of a comprehensive assessment of all viable areas or total construction anD servicing costs, either through the applIcatIon of transportatIon moDellIng or DerIveD from a fIrst prIncIples approach.