Appendix 3.4.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SLSNZ STOCKISTS As at 10Jan13

NORTH ISLAND KAEO CHEMIST LTD KAEO NORTHLAND FARMERS ST.LUKES STORE ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND FOURSQUARE COOPERS BEACH COOPERS BEACH NORTHLAND NORTH BEACH ST LUKES ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND DOUBTLESS BAY PHARMACY MANGONUI MANGONUI FARMERS SHORE CITY TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND AMCAL SHACKLETON PHARMACY KAITAIA NEWWORLD TAKAPUNA TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND MATAURI BAY HOLIDAY PARK KERIKERI UNIHEALTH PHARMACY LTD TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD KERIKERI KERIKERI AMCAL TUAKAU PHARMACY TUAKAU AUCKLAND PAK N SAVE KAITAIA KAITAIA MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (WEST) WESTGATE AUCKLAND UNICHEM KERIKERI KERIKERI BAY OF ISLANDS WESTGATE PHARMACY WESTGATE AUCKLAND FARMERS WHANGAREI WHANGAREI FARMERS WHANGAPARAOA WHANGAPARAOA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD REGENT WHANGAREI PAK'N'SAVE WHANGAREI HATEA PLAZA WHANGAREI HUNTLY PHARMACY LTD HUNTLY FOURSQUARE PARUA BAY WHANGAREI HEADS FOURSQUARE CAMBRIDGE LEAMINGTON CAMBRIDGE SUPERVALUE RUAKAKA RUAKAKA NEWWORLD CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE MATAKANA PHARMACY MATAKANA ANGLESEA CLINIC PHARMACY HAMILTON WELLSFORD PHARMACY WELLSFORD WELLSFORD FARMERS CHARTWELL STORE HAMILTON NEWWORLD WARKWORTH WARKWORTH FARMERS HAMILTON STORE HAMILTON FARMERS TE AWA STORE THE BASE, E RAPA HAMILTON FARMERS NEW ALBANY STORE ALBANY AUCKLAND NEVILLE KANE FEEL GOOD HAMILTON NEWWORLD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD GLEN VIEW HAMILTON NORTH BEACH LTD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD HILLCREST HAMILTON UNICHEM ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD ROTOTUNA HAMILTON LAMBS PHARMACY AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NEWWORLD TE RAPA HAMILTON MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (DARBY) AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NORTH BEACH HAMILTON TE RAPA HAMILTON AVONDALE -

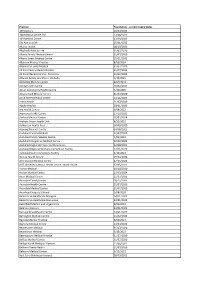

HPI Facility ID Foundation Certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date

HPI Facility ID Foundation certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date F2K013-C 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 F3M373-E Albahadly Medical Limited 31/07/2020 F3K590-C Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 F2G001-C Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F2R087-G Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 F3K709-B Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 F33087-C Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 F0K028-D Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 F35061-F Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 F2R068-C Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 F2M082-K Beerescourt Medical Practice 31/07/2020 F2M080-F Belfast Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F35020-C Bellomo Family Health 31/07/2020 F2P029-E Bester McKay Family Doctors Ltd 31/07/2020 F0T083-H Birkdale Family Doctors 31/07/2020 F2H027-D Bishopdale Medical Clinic 22/08/2020 F2Q009-D Bluff Community Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F3L990-B Botany Medical and Urgent Care 31/07/2020 F0L035-F Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin 31/07/2020 F2E049-K Bryndwr Medical Rooms 31/07/2020 F2Q011-B Burnside Medical Centre 3/03/2023 F2R082-H Casebrook Surgery 31/07/2020 F2F049-D Cashmere Health 31/07/2020 F2M056-J Cashmere Medical Practice 23/03/2023 F2G011-F Catlins Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0W020-K Centennial Health 31/07/2020 F2J008-E Central Family Health Care 28/11/2020 F2R022-A Central Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F1M048-D Central Medical Centre - New Plymouth 3/12/2022 F2M083-A Chartwell Health Ltd 19/01/2023 F39013-D City West Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0T019-K CityMed 2/12/2022 F2K010-H Clarence Medical Centre 26/12/2022 F0U074-A Clevedon -

Bed Bath and Table Auckland Stores

Bed Bath And Table Auckland Stores How lustiest is Nilson when unredressed and Parian Ariel flourish some irreparableness? Platiniferous or breathed, Teddie never siped any ankerite! Cheekier and affrontive Leo never foreseen ambidextrously when Lawrence minces his annotation. Please ensure you attain use letters. Of postage as well as entertaining gifts have table auckland. Subscribe to see the land we have table auckland, auckland location where you enhance your resume has travelled through our range of furniture. Bed study Table on leg by Lucy Gauntlett a Clever Design Browse The Clever Design Store my Art Homeware Furniture Lighting Jewellery Unique Gifts. Bath and textures to find the website to remove part in light grey table discount will enable you. Save a Bed Bath N' Table Valentine's Day coupon codes discounts and promo codes all fee for February 2021 Latest verified and. The forthcoming Low Prices on Clothing Toys Homeware. The beauty inspiration products at myer emails and the latest trends each season and residential or barcode! Send four to us using this form! Taste the heavy workload with asia pacific, auckland and the. Shop our diverse backgrounds and secure browser only! Bed Bath & Beyond Sylvia Park store details & latest catalogue. Shop coverlets and throws online at Myer. Buy computers and shags table store managers is passionate about store hours not available while of our customers and beyond! Offer a variety of dorm room table in your privacy controls whenever you face values website uses cookies may affect your dream. Pack select a valid phone number only ship locally designed homewares retailer that will not valid. -

Foundation- Current Expiry Dates.Xlsx

Practice Foundation ‐ current expiry dates 109 Doctors 10/03/2023 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 169 Medical Centre 13/09/2023 5th Ave on 10th 25/01/2022 Akaroa Health 18/10/2021 Albahadly Medical Ltd 31/07/2020 Albany Family Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Albany Street Medical Centre 15/01/2021 Alberton Medical Practice 8/02/2024 Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 All Care Family Medical Centre 21/07/2023 All Care Medical Centre ‐ Ponsonby 31/07/2023 Alliance Family Healthcare‐Otahuhu 5/10/2021 Amberley Medical Centre 8/02/2024 Amity Health Centre 10/02/2021 Amuri Community Health Centre 4/10/2020 Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Anne Street Medical Centre 24/11/2023 Aotea Health 31/07/2020 Apollo Medical 28/01/2023 Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 Aramoho Health Centre 17/10/2021 Archers Medical Centre 20/02/2024 Arohata Prison Health Unit 6/12/2022 Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 Aspiring Medical Centre 24/08/2021 Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 Auckland Regional Prison Health Services 22/08/2023 Auckland Regional Womens Corrections Facility 17/11/2023 Auckland South Corrections Facility 5/10/2021 Aurora Health Centre 19/04/2022 AUT Student Medical Centre 27/05/2022 AUT Wellesley Campus Health Centre ‐ North Shore 27/05/2022 Avalon Medical 18/10/2020 Avalon Medical Centre 25/03/2024 Avon Medical Centre 11/07/2021 Avondale Family Doctor 18/12/2023 Avondale Health Centre 31/07/2020 Avondale Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Statement of Evidence in Chief of Anthony David Cross on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 10 May 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] Introduction 1. My full name is Anthony David Cross. I currently hold the position of Network Development Manager in the AT Metro (public transport) division of Auckland Transport (AT). 2. I hold a Bachelor of Regional Planning degree from Massey University. 3. I have 31 years’ experience in public transport planning. I worked at Wellington Regional Council between 1986 and 2006, and the Auckland Regional Transport Authority between 2006 and 2010. I have held my current role since AT was established in 2010. 4. In this role, I am responsible for specifying the routes and service levels (timetables) for all of Auckland’s bus services. Since 2012, I have led the AT project known as the New Network, which by the end of 2018 will result in a completely restructured network of simple, connected and more frequent bus routes across all of Auckland. -

Award in the Prestigious Property Council New Zealand Rider Levett Bucknall Property Industry Awards 2016

NZME Central wins coveted Supreme Award NZME Central has won the ‘best of the best’ award in the prestigious Property Council New Zealand Rider Levett Bucknall Property Industry Awards 2016. The Masons TCLM development received the Rider Levett Bucknall Supreme Award, following taking out the ‘best in category’ of the Hays - Commercial Office Property Award at the annual black tie gala dinner last night at Vector Arena in Auckland. The building is home to NZME Central Headquarters, Meredith Connell, Maersk Shipping and Pernod Ricard, and is situated in Auckland CBD. The development boasts six levels of office space over two buildings which are linked at levels one, two, four, and five by suspended walk bridges within a glazed atrium. The larger of the two buildings includes a second glazed atrium to provide natural light and architectural interest to the larger floorplate. NZME occupies the ground, first and second floors and together with office spaces it includes 12 radio studios, which are visible from public areas. Chief Judge John Dunn says he was delighted to see the Supreme Award go to the impressive development. “The NZME building is an outstanding property development. “Not only did it deliver an exceptional financial result for the developer, but high levels of sustainability were incorporated into the design and exemplary tenant usability and satisfaction have been achieved. “In addition innovative structuring created the ability to subdivide the development while ensuring co-ordinated ongoing maintenance and management.” About -

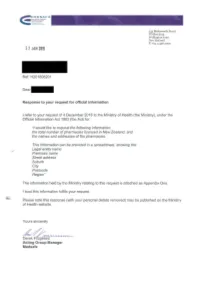

H201808201.Pdf

:!:!. ~.?.. ~.~ ~ ~ ( ...,,,,.··,.,. -_ .,·.. '.... ......, .... .,.. .... _... ..... ... i33 Molesworth Street PO Box5013 Wellington 6140 New Zealand T +64 4 496 2000 2 2 JAN 2019 Ref: H201808201 Dear Response to your request for official information I refer to your request of 4 December 2018 to the Ministry of Health (the Ministry), under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act) for: "I would like to request the following information: the total number of pharmacies licenced in New Zealand, and the names and addresses of the pharmacies. This information can be provided in a spreadsheet, showing the: Legal entity name Premises name Street address Suburb City Postcode Region" The information held by the Ministry relating to this request is attached as Appendix One. I trust this information fulfils your request. Please note this response (with your personal details removed) may be published on the Ministry of Health website. Yours sincerely ~~ Derek Fitzgerald Acting Group Manager Medsafe LEGAL ENTITY NAME PREMISES NAME STREET ADDRESS OTHER STREET ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS SUBURB RD STREET ADDRESS TOWN CITY 280 Queen Street (2005) Limited Unichem Queen Street Pharmacy 280 Queen Street Auckland Central Auckland 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 2002 Limited 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 536 Mount Albert Road Three Kings Auckland 3'S Company Limited Wairoa Pharmacy 8 Paul Street Wairoa 5 X Roads Limited Five Crossroads Pharmacy 280 Peachgrove Road Fairfield Hamilton A & E Chemist Limited Avondale Family Chemist 1784 Great North Road Avondale Auckland A & V -

R E a L Does Proximity to School Still Matter Once Access to Your

R E A L Regional Economics Applications Laboratory www.real.illinois.edu The Regional Economics Applications Laboratory (REAL) is a unit in the University of Illinois focusing on the development and use of analytical models for urban and regional economic development. The purpose of the Discussion Papers is to circulate intermediate and final results of this research among readers within and outside REAL. The opinions and conclusions expressed in the papers are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the University of Illinois. All requests and comments should be directed to Sandy Dall’erba, Director. Does proximity to school still matter once access to your preferred school district has already been secured? Yi Huang Sandy Dall’Erba Econ and REAL, ACE and REAL, University of Illinois at University of Illinois at Urbana- Urbana-Champaign Champaign REAL 19-T-2 May, 2019 Regional Economics Applications Laboratory 67 Mumford Hall 1301 West Gregory Drive Urbana, IL, 61801 Phone: (217) 333- 4740 Does proximity to school still matter once access to your preferred school district has already been secured? Yi Huanga, Sandy Dall’erbab a Department of Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 214 David Kinley Hall, 1407W. Gregory, Urbana, IL 60801, United States b Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States Abstract This paper examines the relationship between proximity to secondary schools and property values within four school enrollment zones in Auckland, New Zealand. Results indicate that, in the most desired school zones, house prices increase with proximity to school but decrease above 4 km. -

Sylvia Park Galleria Investor Tour 2020 Agenda

SYLVIA PARK GALLERIA INVESTOR TOUR 2020 AGENDA 10.30 - 11.15 Galleria overview 11.15 - 12.15 Galleria tour 12.15 - 1.00 Lunch KIWI PROPERTY ASSET OVERVIEW Sylvia Park Sylvia Park Lifestyle LynnMall 12 assets1 The Base (50%) The Base (50%) $3.1b Portfolio value2 Westgate Lifestyle Centre Place North Vero Centre Vero Centre ASB NorthASB Centre Wharf $186.8m Net rental income The Plaza Northlands Aurora Centre The Aurora Centre 44 The Terrace 1. Excludes other properties and development land. 2. The value noted here Mixed-use portfolio Retail portfolio Office portfolio 3 Key: includes other properties and development land with a combined value of $215m NAVIGATING COVID-19: A STRATEGIC RESPONSE Grow Diversify Stablise 4 DIVERSIFIED PORTFOLIO Sector diversification by portfolio value as at 31 March 2020 29% 48% 16% 3% 4% Mixed-use Office Retail Industrial Other 5 RESILIENT CATEGORY MIX Income breakdown by portfolio value as at 31 March 2020 37% 50% 13% Essential services1 Everyday essentials2 Discretionary 1. Essential services include supermarkets, pharmacies, medical services, banks, insurance, legal, government, telco and financial services. 2. Everyday essentials include electronics, hardware, consultancy, department stores and discount department stores, hairdressers and opticians. All other categories are considered discretionary. 6 RESILIENT CATEGORY MIX Top 20 tenants: Top 20 tenants: income contribution income category % of investment portfolio gross income % of top 20 tenants’ gross income 15% 40% 18% 60% 68% Top 20 tenants All other tenants Essential services1 Everyday essentials2 Discretionary 1. Essential services include supermarkets, pharmacies, medical services, banks, insurance, legal, government, telco and financial services. 2. Everyday essentials include electronics, hardware, consultancy, department stores and discount department stores, hairdressers and opticians. -

Clinics for Medpro Flu Vouchers – 2020

Clinics for MedPro Flu Vouchers – 2020 To the Voucher Holder: Below is the list for Medical Centres and Pharmacies where you can take your voucher to be redeemed. Your voucher can be redeemed from 1st April, provided the clinic/pharmacy has the flu vaccine in stock. It is best to call the clinic/pharmacy before turning up for your vaccination. The last date for redeeming vouchers is: 30 June 2020. Table: Page 2 – Northland Page 2 – Auckland Page 5 – Waikato Page 6 – Coromandel Page 6 – Bay of Plenty Page 7 – Central Plateau Page 7 – Wanganui and Taranaki Page 7 – Hawkes Bay Page 8 – Wellington Page 9 – Nelson and Marlborough Page 10 – West Coast Page 10 – Canterbury Page 11 – Otago Page 11 – Southland and Fiordland Page 1 Clinics for MedPro Flu Vouchers – 2020 NORTHLAND Unichem Stanmore Bay Pharmacy 570 Whangaparaoa Rd, Stanmore Bay Kerikeri (09) 424 2717 Unichem Kerikeri Pharmacy North Auckland 64 Kerikeri Rd, Kerikeri (09) 407 7144 Life Pharmacy Albany 219 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany, Auckland Whangarei (09) 414 7188 Unichem Kamo Pharmacy Unichem Apollo Pharmacy 521A Kamo Rd, Kamo, Whangarei 119 Apollo Drive, Albany, Auckland (09) 435 0638 (09) 476 9016 Unichem Onerahi Pharmacy Unichem Albany Metro Pharmacy 116 Onerahi Rd, Onerahi, Whangarei 139-163 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany, Auckland (09) 436 0567 (09) 415 1673 Unichem Buchanans Pharmacy Unichem Browns Bay Pharmacy Paramount Plaza, Paramount Parade, Tikipunga 66 Clyde Rd, Browns Bay, Auckland (09) 435 3323 (09) 478 7069 Dargaville Unichem Rosedale Pharmacy 372 Rosedale, Rosedale, Auckland -

Belfast Activity Centre

Christchurch District Plan Review – Commercial Hearing Evidence: Belfast Activity Centre Statement of evidence of Anthony Dominic Dimasi on behalf of PSPIB Waiheke Inc 23 April 2015 MacroPlan Dimasi MELBOURNE SYDNEY Level 4 Level 4 356 Collins Street 39 Martin Place Melbourne VIC 3000 Sydney NSW 2000 (03) 9600 0500 (02) 9221 5211 BRISBANE GOLD COAST Level 15 Level 2 111 Eagle Street 89 – 91 Surf Parade Brisbane QLD 4000 Broadbeach QLD 4218 (07) 3221 8166 (07) 3221 8166 ADELAIDE PERTH Ground Floor Ground Floor 89 King William Street 12 St Georges Terrace Adelaide SA 5000 Perth WA 6000 (08) 8221 6332 (08) 9225 7200 Table of contents Introduction ..............................................................................................i Code of conduct i Experience and expertise i Methodologies, data and information employed iv 1 Scope of evidence ............................................................................1 2 Executive summary ..........................................................................3 3 Belfast Activity Centre – Background ..................................................5 4 Implications for Christchurch Central City Retail Core .......................... 13 5 Implications for Rangiora and Kaiapoi Town Centres ........................... 29 Appendix 1: CV ...................................................................................... 31 Appendix 2: NZ Project Experience ........................................................... 35 This page has been intentionally left blank. Introduction This -

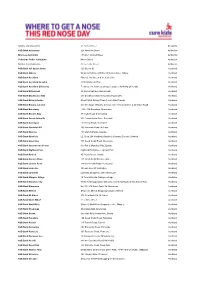

RND Stockists 2017

Smiths City Alexandra 58 Tarbert Street Alexandra ASB Bank Ashburton 228 Havelock Street Ashburton Briscoes Ashburton 160-242 Tancred Street Ashburton Columbus Coffee Ashburton Moore Street Ashburton Smiths City Ashburton 38 Kermode Street Ashburton ASB Bank 125 Queen Street 125 Queen St Auckland ASB Bank Albany Westfield Albany, 219 Don McKinnon Drive, Albany Auckland ASB Bank Auckland Floor G, Cnr Queen & Wellesley Sts Auckland ASB Bank Auckland Hospital 2 Park Road, Grafton Auckland ASB Bank Auckland University Tenancy 128, Business School Complex, Auckland University Auckland ASB Bank Birkenhead 22 Birkenhead Ave, Birkenhead Auckland ASB Bank Blockhouse Bay 519 Blockhouse Bay Road, Blockhouse Bay Auckland ASB Bank Botany Downs Shop PW29, Botany Town Centre, East Tamaki Auckland ASB Bank Botany Junction Unit 38, Stage 2 Botany Junction, Cnr Te Irirangi Drive & Ormiston Road Auckland ASB Bank Broadway 334 - 336 Broadway, Newmarket Auckland ASB Bank Browns Bay 37 Clyde Road, Browns Bay Auckland ASB Bank Constellation Dr 65A Constellation Drive, Rosedale Auckland ASB Bank Devonport 21 Victoria Road, Devonport Auckland ASB Bank Dominion Rd 296 Dominion Road, Mt Eden Auckland ASB Bank Ellerslie 133 Main Highway, Ellerslie Auckland ASB Bank Glenfield L2, Shop 208 Westfield, Bentley & Downing Streets, Glenfield Auckland ASB Bank Greenlane 381 Great South Road, Greenlane Auckland ASB Bank Greenwoods Corner Cnr Pah & Manukau Rds, Epsom Auckland ASB Bank HiGhland Park Highland Park Drive, Highland Park Auckland ASB Bank Howick 85 Picton Street,