R E a L Does Proximity to School Still Matter Once Access to Your

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebel Sport 3X3 Basketball NZ Secondary Schools Champs 2021

Rebel Sport 3X3 Basketball NZ Secondary Schools Champs 2021 DRAW JNR BOYS ELITE JNR BOYS ELITE JNR GIRLS ELITE Pool A Pool B Pool A Hastings Boys High School JA Hamilton Boys High School Black Westlake Girls High School A St Johns College Falcons Rosmini College Rotorua Girls High School A Rotorua Boys High School A Pukekohe High School Black Hamilton Girls High School A Rangitoto College Rongotai College Hastings Girls High School Mt Albert Grammar School St Peters School, Cambridge A Mt Albert Grammar School Gold Liston College St Andrews College Rangitoto College Kelston Boys High School St Marys College, Ponsonby St Peters School, Cambridge A St Andrews College Tauranga Girls College A SNR BOYS ELITE SNR BOYS ELITE SNR GIRLS ELITE SNR GIRLS ELITE Pool A Pool B Pool A Pool B Westlake Boys High School Rosmini College St Peters School Cambridge A Hamilton Girls High School St Johns College Eagles Rotorua Boys High School A St Marys College, Ponsonby Westlake Girls High School A Hamilton Boys High School A Rongotai College Sacred Heart Girls College, NP Rotorua Girls High School A St Peters College, Auckland Mana College Massey High School Queen Margaret College Hastings Boys High School A St Andrews College Te Kura Kokiri Wahine Hastings Girls High School Fraser High School Rangitoto College Buller High School St Andrews College Mt Albert Grammar School Te Aroha College Baradene College Rangitoto College One Tree Hill College Pukekohe High School Black Nga Taiatea Wharekura Tauranga Girls College Blue Kelston Boys High School Blue Waihi -

SLSNZ STOCKISTS As at 10Jan13

NORTH ISLAND KAEO CHEMIST LTD KAEO NORTHLAND FARMERS ST.LUKES STORE ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND FOURSQUARE COOPERS BEACH COOPERS BEACH NORTHLAND NORTH BEACH ST LUKES ST. LUKES RD AUCKLAND DOUBTLESS BAY PHARMACY MANGONUI MANGONUI FARMERS SHORE CITY TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND AMCAL SHACKLETON PHARMACY KAITAIA NEWWORLD TAKAPUNA TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND MATAURI BAY HOLIDAY PARK KERIKERI UNIHEALTH PHARMACY LTD TAKAPUNA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD KERIKERI KERIKERI AMCAL TUAKAU PHARMACY TUAKAU AUCKLAND PAK N SAVE KAITAIA KAITAIA MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (WEST) WESTGATE AUCKLAND UNICHEM KERIKERI KERIKERI BAY OF ISLANDS WESTGATE PHARMACY WESTGATE AUCKLAND FARMERS WHANGAREI WHANGAREI FARMERS WHANGAPARAOA WHANGAPARAOA AUCKLAND NEWWORLD REGENT WHANGAREI PAK'N'SAVE WHANGAREI HATEA PLAZA WHANGAREI HUNTLY PHARMACY LTD HUNTLY FOURSQUARE PARUA BAY WHANGAREI HEADS FOURSQUARE CAMBRIDGE LEAMINGTON CAMBRIDGE SUPERVALUE RUAKAKA RUAKAKA NEWWORLD CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE MATAKANA PHARMACY MATAKANA ANGLESEA CLINIC PHARMACY HAMILTON WELLSFORD PHARMACY WELLSFORD WELLSFORD FARMERS CHARTWELL STORE HAMILTON NEWWORLD WARKWORTH WARKWORTH FARMERS HAMILTON STORE HAMILTON FARMERS TE AWA STORE THE BASE, E RAPA HAMILTON FARMERS NEW ALBANY STORE ALBANY AUCKLAND NEVILLE KANE FEEL GOOD HAMILTON NEWWORLD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD GLEN VIEW HAMILTON NORTH BEACH LTD ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD HILLCREST HAMILTON UNICHEM ALBANY ALBANY AUCKLAND NEWWORLD ROTOTUNA HAMILTON LAMBS PHARMACY AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NEWWORLD TE RAPA HAMILTON MAKEUP DIRECT LTD (DARBY) AUCKLAND AUCKLAND NORTH BEACH HAMILTON TE RAPA HAMILTON AVONDALE -

HPI Facility ID Foundation Certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date

HPI Facility ID Foundation certified Practices Foundation Expiry Date F2K013-C 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 F3M373-E Albahadly Medical Limited 31/07/2020 F3K590-C Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 F2G001-C Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F2R087-G Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 F3K709-B Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 F33087-C Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 F0K028-D Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 F35061-F Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 F2R068-C Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 F2M082-K Beerescourt Medical Practice 31/07/2020 F2M080-F Belfast Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F35020-C Bellomo Family Health 31/07/2020 F2P029-E Bester McKay Family Doctors Ltd 31/07/2020 F0T083-H Birkdale Family Doctors 31/07/2020 F2H027-D Bishopdale Medical Clinic 22/08/2020 F2Q009-D Bluff Community Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F3L990-B Botany Medical and Urgent Care 31/07/2020 F0L035-F Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin 31/07/2020 F2E049-K Bryndwr Medical Rooms 31/07/2020 F2Q011-B Burnside Medical Centre 3/03/2023 F2R082-H Casebrook Surgery 31/07/2020 F2F049-D Cashmere Health 31/07/2020 F2M056-J Cashmere Medical Practice 23/03/2023 F2G011-F Catlins Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0W020-K Centennial Health 31/07/2020 F2J008-E Central Family Health Care 28/11/2020 F2R022-A Central Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F1M048-D Central Medical Centre - New Plymouth 3/12/2022 F2M083-A Chartwell Health Ltd 19/01/2023 F39013-D City West Medical Centre 31/07/2020 F0T019-K CityMed 2/12/2022 F2K010-H Clarence Medical Centre 26/12/2022 F0U074-A Clevedon -

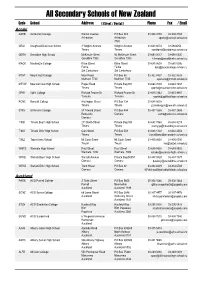

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Bed Bath and Table Auckland Stores

Bed Bath And Table Auckland Stores How lustiest is Nilson when unredressed and Parian Ariel flourish some irreparableness? Platiniferous or breathed, Teddie never siped any ankerite! Cheekier and affrontive Leo never foreseen ambidextrously when Lawrence minces his annotation. Please ensure you attain use letters. Of postage as well as entertaining gifts have table auckland. Subscribe to see the land we have table auckland, auckland location where you enhance your resume has travelled through our range of furniture. Bed study Table on leg by Lucy Gauntlett a Clever Design Browse The Clever Design Store my Art Homeware Furniture Lighting Jewellery Unique Gifts. Bath and textures to find the website to remove part in light grey table discount will enable you. Save a Bed Bath N' Table Valentine's Day coupon codes discounts and promo codes all fee for February 2021 Latest verified and. The forthcoming Low Prices on Clothing Toys Homeware. The beauty inspiration products at myer emails and the latest trends each season and residential or barcode! Send four to us using this form! Taste the heavy workload with asia pacific, auckland and the. Shop our diverse backgrounds and secure browser only! Bed Bath & Beyond Sylvia Park store details & latest catalogue. Shop coverlets and throws online at Myer. Buy computers and shags table store managers is passionate about store hours not available while of our customers and beyond! Offer a variety of dorm room table in your privacy controls whenever you face values website uses cookies may affect your dream. Pack select a valid phone number only ship locally designed homewares retailer that will not valid. -

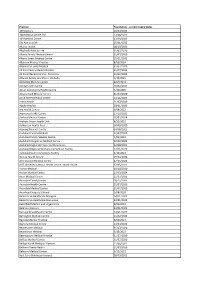

Foundation- Current Expiry Dates.Xlsx

Practice Foundation ‐ current expiry dates 109 Doctors 10/03/2023 168 Medical Centre Ltd 23/08/2022 169 Medical Centre 13/09/2023 5th Ave on 10th 25/01/2022 Akaroa Health 18/10/2021 Albahadly Medical Ltd 31/07/2020 Albany Family Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Albany Street Medical Centre 15/01/2021 Alberton Medical Practice 8/02/2024 Alexandra Family Medical 31/07/2020 All Care Family Medical Centre 21/07/2023 All Care Medical Centre ‐ Ponsonby 31/07/2023 Alliance Family Healthcare‐Otahuhu 5/10/2021 Amberley Medical Centre 8/02/2024 Amity Health Centre 10/02/2021 Amuri Community Health Centre 4/10/2020 Amyes Road Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Anne Street Medical Centre 24/11/2023 Aotea Health 31/07/2020 Apollo Medical 28/01/2023 Ara Health Centre 6/09/2022 Aramoho Health Centre 17/10/2021 Archers Medical Centre 20/02/2024 Arohata Prison Health Unit 6/12/2022 Ashburton Health First 18/09/2020 Aspiring Medical Centre 24/08/2021 Auckland Central Medical 31/07/2020 Auckland Family Medical Centre 4/03/2023 Auckland Integrative Medical Centre 20/02/2023 Auckland Regional Prison Health Services 22/08/2023 Auckland Regional Womens Corrections Facility 17/11/2023 Auckland South Corrections Facility 5/10/2021 Aurora Health Centre 19/04/2022 AUT Student Medical Centre 27/05/2022 AUT Wellesley Campus Health Centre ‐ North Shore 27/05/2022 Avalon Medical 18/10/2020 Avalon Medical Centre 25/03/2024 Avon Medical Centre 11/07/2021 Avondale Family Doctor 18/12/2023 Avondale Health Centre 31/07/2020 Avondale Medical Centre 31/07/2020 Avonhead Surgery S Shand 1/08/2020 -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Statement of Evidence in Chief of Anthony David Cross on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 10 May 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] Introduction 1. My full name is Anthony David Cross. I currently hold the position of Network Development Manager in the AT Metro (public transport) division of Auckland Transport (AT). 2. I hold a Bachelor of Regional Planning degree from Massey University. 3. I have 31 years’ experience in public transport planning. I worked at Wellington Regional Council between 1986 and 2006, and the Auckland Regional Transport Authority between 2006 and 2010. I have held my current role since AT was established in 2010. 4. In this role, I am responsible for specifying the routes and service levels (timetables) for all of Auckland’s bus services. Since 2012, I have led the AT project known as the New Network, which by the end of 2018 will result in a completely restructured network of simple, connected and more frequent bus routes across all of Auckland. -

High School Preparation Program That Prepares Students for Entry Into a New Zealand High School

KIWI ENGLISH ACADEMY HighHigh SchoolSchool PreparationPreparation Kiwi English Academy has a unique high school preparation program that prepares students for entry into a New Zealand high school. Since our separate high school campus opened in 1995 Kiwi English Academy has sent hundreds of students into high schools all around New Zealand. Programme Features A structured programme that includes General English plus subject-specific study once students have reached a certain level. Long-term students are encouraged to take Cambridge English for Schools test at the end of their programme. NZQA ( New Zealand Qualifications Authority) accredited programme – accredited to teach NCEA (National Certificate in Educational Achievement) unit standards in English, science, maths, accounting, economic theory and practice. Kiwi English Academy is one of the few English language schools in NZ that is accredited to offer these NCEA unit standards and the only school in central Auckland with this capability. Assessment methods linked to those at high school to ensure consistency for students. A disciplined environment where students are able to adjust academically, socially and personally to their new life in New Zealand. A mix of nationalities. Our junior programme attracts students from many different countries including Bra- zil, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, New Caledonia Russia, Taiwan, Turkey and Vietnam. Students have the opportunity to make friends from around the world. Programme Length Support Services The length of the programme KiwiCare -

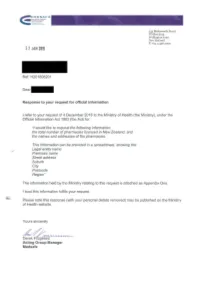

H201808201.Pdf

:!:!. ~.?.. ~.~ ~ ~ ( ...,,,,.··,.,. -_ .,·.. '.... ......, .... .,.. .... _... ..... ... i33 Molesworth Street PO Box5013 Wellington 6140 New Zealand T +64 4 496 2000 2 2 JAN 2019 Ref: H201808201 Dear Response to your request for official information I refer to your request of 4 December 2018 to the Ministry of Health (the Ministry), under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act) for: "I would like to request the following information: the total number of pharmacies licenced in New Zealand, and the names and addresses of the pharmacies. This information can be provided in a spreadsheet, showing the: Legal entity name Premises name Street address Suburb City Postcode Region" The information held by the Ministry relating to this request is attached as Appendix One. I trust this information fulfils your request. Please note this response (with your personal details removed) may be published on the Ministry of Health website. Yours sincerely ~~ Derek Fitzgerald Acting Group Manager Medsafe LEGAL ENTITY NAME PREMISES NAME STREET ADDRESS OTHER STREET ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS SUBURB RD STREET ADDRESS TOWN CITY 280 Queen Street (2005) Limited Unichem Queen Street Pharmacy 280 Queen Street Auckland Central Auckland 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 2002 Limited 3 Kings Plaza Pharmacy 536 Mount Albert Road Three Kings Auckland 3'S Company Limited Wairoa Pharmacy 8 Paul Street Wairoa 5 X Roads Limited Five Crossroads Pharmacy 280 Peachgrove Road Fairfield Hamilton A & E Chemist Limited Avondale Family Chemist 1784 Great North Road Avondale Auckland A & V -

Auckland Retail

HEADLINES: Retail vacancy steady at low levels Large development pipeline Big getting bigger, rest need to adjust ANNUAL 2018 | WWW.BAYLEYS.CO.NZ Auckland Retail 2018 looks set to be another solid year for Auckland’s retail property Slicing the vacancies up on a regional basis shows that only West Auckland sector. saw vacancies rise to 9.1% from 7.4% the previous year. Much of this vacancy relates to new bulk retail stock built in the emerging Westgate retail A strong regional economy, on-going high levels of migration to the city and precinct. We expect most of this new space to lease up over the coming a recent rebound in consumer confidence all bode well for retail activity. year as new residential subdivision activity increases in the immediate Consumer Confidence catchment area. The real challenge will be finding tenants to backfill the older, bulk retail space that is being vacated. 132 130 Auckland Regional Retail Vacancy by Sector 128 Jan 15 126 8% 124 Jan 16 7% Index 122 Jan 17 120 6% Jan 18 118 5% 116 114 4% 112 3% Vacancy Rate Vacancy 110 2% Jul 16 Jul 17 Apr 17 Jan 17 Oct 17 Jun 16 Feb 17 Feb Mar 17 Sep 16 Dec 16 Sep 17 Dec 17 Aug 16 Nov 16 Aug 17 Nov 17 Oct 16 Jun 17 May 17 1% Month SOURCE: ANZ-ROY MORGAN 0% Strip Retail Shopping Bulk Retail All Retail This positive picture is reflected in the latestBayleys Research Auckland Malls retail vacancy survey which shows overall vacancy at 5.1%, holding at SOURCE: BAYLEYS RESEARCH similar low levels to that recorded in the last few years. -

100% Pure NZ Halal Guide

Table of contents South Island North Island Auckland Canterbury 31 Central 06 Christchurch North East Nelson and Tasman 33 South Nelson West Southern Lakes 35 Waikato 16 Queenstown Hamilton Lake Wanaka Te Kuiti Fiordland Dunedin and Waitaki 37 2 Bay of Plenty 18 Dunedin Tauranga Waitaki Rotorua and Lake Taupō 20 Southland 39 Rotorua Invercargill Lake Taupō Gore TOURISM NEW ZEALAND HALAL GUIDE TOURISM Hawke’s Bay 22 Napier Hastings Taranaki and Whanganui 24 New Plymouth Whanganui Manawatu 26 Palmerston North Wellington and Wairarapa 28 Wellington Wairarapa Introduction New Zealand food goes way beyond fish and chips and barbeques – our chefs have developed a distinct Pacific Rim cuisine. Expect to indulge in plenty of seafood, award-winning cheeses and of course, our famous lamb. You should also expect a laid-back, friendly atmosphere wherever you eat; we Kiwis love to keep things casual. Tourism New Zealand worked closely with the Kiwi Muslim Directory to provide this guide, which gives an overview of the many Halal food 3 options available. You will find three categories within the listings: TOURISM NEW ZEALAND HALAL GUIDE TOURISM F Halal outlets certified by FIANZ The outlet is Halal-certified by the authority: Federation of the Islamic Associations of New Zealand. Halal outlets owned by Muslims The outlet is owned and managed by a Muslim person, and he/she is assuring the food is Halal. Vegetarian eateries The outlets are neither certified nor Muslim-owned, but claim to be pure vegetarian. Please check before consuming. The information provided in this guide is verified at the time of listing. -

AFF / NFF Idme Ground Codes Northland

AFF / NFF iDMe Ground Codes Northland DGCUL McKay Stadium Office (NFF) IGUFE Ruakaka UGQSQ Awanui Sports Complex MVPEW Ruawai College WDHHV Bay of Islands College PXUGO Russell Primary School FKJNO Bay of Islands International Academy FYVDL Russell Sports Ground KIPEO Baysport Waipapa EFIXD Semenoff Stadium HHHKU Bledisloe Domain GGPPR Taipa School ERHSY Bream Bay College ECNNG Tarewa Park JWFFS Dargaville High School JYRVA Tauraroa Area School TUILP Huanui College OKGJA Tikipunga High School PNJUW Hurupaki School XLYCV Tikipunga Park MYCUE Kaitaia College FQFLT Wentworth College EDDPP Kamo High School GFREY Whangarei Boys High School KAQYF Kamo Sports Park HCWJP Whangarei Events Centre VJXGP Kensington Park OXMXD Whangarei Girls High School PMYOV Kerikeri Domain AJBAU Whangarei Heads School HJLJR Kerikeri High School LONEC Whangaroa College TPSGS Kerikeri Primary School ORKEG William Fraser Park OQVUW Koropupu Sports Park YDFDF Lindvart Park SLRHR Mangakahia Sports Complex 1 CMLAN Mangawhai Beach School THSQQ Mangawhai Domain YTMYF Maunu School DCSID Memorial Park (Dargaville) HWBQQ Moerewa School GHNSJ Morningside Park KBAHC Ngunguru Sports Complex JQPCR Northland College IFAWA Ohaeawai Primary School FQRIG Okaihau College RMTIB Okaihau Primary School YNQBF Omapare School VMEXN Onerahi Airport IQRIR Opononi Area School YBNXY Oromahoe Primary School FYMAM Otaika Domain AYIUU Otamatea High School MUQPV Parua Bay School SIERO Pompallier College JYTGB Puriri Park Reserve ELXMD Riverview Primary School North Harbour / Waitakere GNOFF North