Visual Grounded Analysis: Developing and Testing a Method for Preliminary Visual Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Westfield 4Th of July Projscta

Going for glory TWo thumbs up Salute America Athletes prepare for Kids' Stuff seeks Display your pride Garden State Games youngsters' reviews on the 4th of July Sam pag#> A-9 %— baek pag« of INSIDE Record Sol : Thursday. July 1,1993 A Forbes Newspaper 50 cents A parting hug A Westfield 4th of July projscta. This (tawing v* be haU July 20 at Ins Steak and Ate; IMountaMd*, NJ. Ths prim In- Park concerts will cfadsa 2antfiicotar T.V.. • git oar- ttcatv wont Apnoono Jewewv and 4^a% a^awtfab^aa^aM frw 44hw^aw ast C^^^aAr mark Fourth fetes and A*. The Uons Club •*» larg- est santoa dub In tw worid win •y LOMMOFFETT 1.4 rraaon iiiemDsrs. For more m- THE RECORD tormalon cal Mke at 664-48B0. Far those spending this holiday weekend in West- Authors wanted field, there are plenty of ways to catch the spirit of TheWs JJJbrarJy to 1776. oompang a M of WestHeld authors Fourth of July festivities begin Thursday night with to b* uMd during Wettfefcfs b> an outdoor concert in Mindowaskin Park. The West- cmtanntol oalspratlon. Thto 1st wfl field Concert band will perform 8-10 p.m. at the tnduds currant residents of West- park's gazebo. laid and people who graw up hem but toe ataswhsm raw. authors of At intermission, a special ceremony sponsored by •don and nonJeson along with the Sons of the American Revolution and the Daugh- writers who have been published In ters of the American Revolution will be held. books, newepapenii magazines or The ceremony will include an appearance from the mon» aohotoiV foumato. -

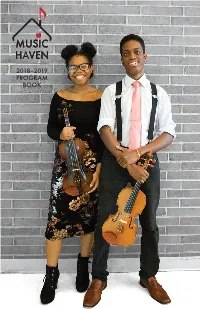

2018–2019 Program Book Title2018–2019 Calendar

TITLE 2018–2019 PROGRAM BOOK TITLE2018–2019 CALENDAR Music Haven students perform dozens of concerts a year throughout the city. Here is a sample of what is in store for this season... Monday, November 12 Veterans Day Concert Mon. Nov 12 – Fri. Nov 16 Fall Studio Recital Week Thursday, December 13 Winter Performance Party Monday, January 21 Martin Luther King, Jr. Concert Mon. March 11 – Fri. March 15 Spring Studio Recital Week Thursday, April 4 Discovery Orchestra Concert at NHSO Wednesday, April 10 Honors Recital Thursday, May 30 Around the World Performance Party Students also play at community spaces such as Smilow Cancer Center, Connecticut Mental Health Center, and public libraries. Front Cover: Jeanna’e and Damani, 2018 Music Haven Graduates. 100% of the students in our first graduating cohort were accepted to four-year colleges. Music Haven • Erector Square • 315 Peck Street, Building 5, Second Floor Mailing Address: Music Haven, 315 Peck Street, Box A 10, New Haven, CT 06513 ATITLE Letter from the Executive Director “Music Haven gave me a home even when home wasn’t home for me.” – Music Haven student If you stop by on a Friday afternoon, you’ll hear it before you even open the door. The discerning ear will pick out a little Britten, some Twinkle, perhaps some solfege coming from Music Theory class, accented by the the sound of snacks and the zipping of backpacks. Open the door and you’ll see it: all life and love and a glorious mess of beautiful young faces and instrument cases in a light-filled expanse of music-making that fills an entire converted factory floor. -

Скачать Elo Electric Light Orchestra Через Торрент

elo_electric_light_orchestra.zip Последовавшее мировое турне коллектив обставил с размахом – команда возила с собой дорогой макет космического корабля, дымовые машины и лазерный дисплей. Сама картина провалилась, но звуковая дорожка имела хороший успех и принесла "оркестрантам" очередную платину.facebook. В начале 1976-го состоялось глобальное американское турне, на котором "Electric Light Orchestra", оправдывая название, впервые использовали лазерные эффекты. Той же осенью вышел альбом "On The Third Day", отмеченный более плотным звуком и ростом Линна как композитора и исполнителя. 8 июля 1949) и бас-гитарист стал Майкл Д'Альбукерк (р. Blue Sky (Re-recorded Greatest Hits) (Japan, 2012 Avalon MICP-30033)SinglesSoundtracksRemastered Editions1973 - ELO21973 - ELO 2 (Japan, 2006 EMI Harvest TOCP-70063 Paper Sleeve)1973 - On The Third Day1974 - Eldorado1975 - Face The Music1976 - A New World Record1977 - Out Of The Blue1977 - Out Of The Blue (30th Anniversary) (EU, 2007 Epic 88697053232)1979 - Discovery1981 - Time1983 - Secret Messages1986 - Balance Of Power2001 - ZoomLive AbumsCompilations & Box-Sets2003 - The Essential Electric Light Orchestra (USA, 2003 Epic Legacy EK 89072)2011 - The Classic Albums Collection (EU, 11CD Box Set Sony Music Epic Legacy 88697873262)Bootlegs1976 - Live In Detroit1976 - Live In Flint1976 - Live USA - Live In San Francisco1976 - Strange Magic - Live In Portsmouth 1976 - The Light Went On Again1978 - Eldorado - Live In Osaka 1978 - Orchestral Encounters Of The Electric Kind - Live In Las Vegas1981 - Hold On Tight - Live At Wembley1982 - Live In Frankfurt1982 - Twilight - Live In Koln1986 - Live In StuttgartГруппа "Electric Light Orchestra" образовалась в октябре 1970 года на развалинах эксцентричного арт-поп-комбо "The Move". В это время в "ELO" произошли дополнительные кадровые перестановки, и к началу сессий второго альбома в команде появились новые игроки, виолончелист Колин Уокер (р. -

Smash Hits Volume 14

k. HSIKkmHHHH^H '•-'«s3s ^^^^IMP^™ FORTNIGHTLY %Mm* ," June 14-27 1979 25p ,,, %r BOOMTOWtf TUBES Words to the TOP SINGLES /.•*-*§ including r k » * <«#£. -* # A6 ** *•' ** * ..I \J*- * 1% It <* IfeM <?* *-V *° •a W^ I worked all through the winter Up The The weather brass and bitter I put away a tenner Each week to make her better Junction And when the time was ready We had to sell the telly By Squeeze on A&M Records Make evenings by the fire Her little kicks inside her I never thought it would happen This morning at 4.50 With me and a girl from Clapham I took her rather nifty Out on a windy common Down to an incubator That night I ain't forgotten Where thirty minutes later When she dealt out the rations She gave birth to a daughter With some or other passions Within a year a walker I said you are a lady She looked just like her mother Perhaps, she said, I may be If there could be another We moved into a basement And now she's two years older With thoughts of our engagement Her mother's with a soldier We stayed in by the telly She left me when my drinking * Although the room was smelly Became a proper stinging We spent our time just kissing The devil came and took me The Railway Arms we're missing From bar to street to bookie But love had got us hooked up No more nights by the telly And all our time it took up No more nights nappies smelling I got a job with Stanley Alone here in the kitchen He said I'd come in handy I feel there's something missing And started me on Monday I beg for some forgiveness So I had a bath on Sunday But begging's not my business I worked eleven hours And she won't write a letter And bought the girl some flowers Words and music by Chris Difford/Glenn Although I always tell her She said she'd seen a doctor Tilbrook. -

The ELO Story

The ELO Story Jeff Lynne was born in industrial Birmingham, England, on December 30, 1947. He grew up in the then- new Shard End City Council housing estate, a high-density residential development built on the eastern edge of the city right after the Second World War, with his parents Philip and Nancy.1 He had a brother and two sisters.2 Lynne’s grandparents in his father’s side were vaudevillian performers.3 More than thirty years later, Lynne would pay tribute to his birthplace in the ELO song “All Over the World,” which mentions Shard End alongside other cities like London, Paris, Amsterdam, Rio de Janiero, and Tokyo. Lynne was a Brummie, a nickname for those blessed with the notoriously thick local Birmingham accent.4 Brummie is shorthand for Brummagem, the popular West Midlands way of pronouncing Birmingham.5 Brummie also has an unfortunate alternative dictionary definition: “counterfeit, cheap, and showy.”6 The accent, which not everyone in the city shares, has even been described as representing the least intelligent dialect in the British Isles.7 Lynne grew up listening to Del Shannon, Roy Orbison,8 Chuck Berry, and The Shadows records.9 His parents did not always approve. About Roy Orbison’s “Only the Lonely” playing on the radio, Jeff said “[t]hey were complaining that it was too sexy, or something, but that voice just made the hairs go up on my neck.”10 At age thirteen, Lynne attended a concert by Del Shannon at Birmingham Town Hall, and from that point on dedicated his life to music.11 He noticed immediately that live performances -

2013 Report to Our Community

85 YEARS 2013 REPORT TO OUR COMMUNITY A 85EXPERIENCE YEARS & EXUBERANCE The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven applies the commitments and aspirations of prior generations to meet the challenges of today and to inspire our community to create the opportunities of tomorrow. In this work, The Community Foundation draws on both the experience of being 85 years old and the exuberance of being 85 years young. To mark the “old history” using the ”young technology” of Pinterest, our Photo Fridays shared photos from the Annual Reports of the last 85 years. You will see these photos throughout this Report. You will also notice our work is displayed within the framework of eight, interconnected issue areas that are critical to building a stronger community. CONTENTS 2 85 YEARS OF BUILDING A STRONGER COMMUNITY 4 WORDS FROM OUR LEADERSHIP EXPERIENCE & EXUBERANCE 6 2013 HIGHLIGHTS 8 GRANTS & DISTRIBUTIONS Support Arts & Culture 12 Meet Basic Needs 18 20 NEW FUNDS Promote Civic Vitality 24 26 FOUNDATION DONORS Boost Economic Success 30 32 giveGreater.org® DONORS Provide Quality Education 36 Protect the Environment 42 Ensure Health & Wellness 48 Nurture Children & Youth 54 56 PROFESSIONAL ADVISORS 57 NETTIE J. DAYTON CIRCLE 58 VOLUNTEERS 60 INVESTMENTS 61 FINANCIALS 62 BOARD OF DIRECTORS & STAFF 85 YEARS OF BUILDING A STRONGER COMMUNITY Since its beginning, The Community Foundation has used funds entrusted to it to build a stronger community. While the community has greatly changed over the decades, the essential ingredients of a strong community are remarkably constant. History reveals that The Foundation has been tackling important issues since our very earliest years, just as we are today. -

Pavia E Provincia: Pavese, Oltrepò Pavese, Lomellina

sabato, 25 settembre 2021 (175) Qual Buon Vento, navigante! » Entra Manifestazioni Monumenti Musei Oasi Associazioni Gruppi musicali Ricette tipiche Informazioni utili Pagina inziale » Musica » Articolo n. 364 del 18 novembre 2002 George Harrison - Brainwashed Articoli della stessa rubrica Con un anticipo di quattro giorni sulla data annunciata esce in tutto il mondo l'album postumo di George Harrison, » Fabrizio Poggi & Chicken Mambo: l'ex Beatles scomparso lo scorso anno dopo una lunga battaglia contro un tumore. Spaghetti Juke Joint » Macadam: Latitudine incrociate Atteso da tutti con curiosità ed impazienza, Brainwashed rischia di deludere chi si aspettava l'album-rivelazione, il » Nat Soul Band: Not so bad capolavoro assoluto. » Far Out Niente di tutto questo: il disco è come tutti gli altri album di Harrison e rispecchia la personalità del chitarrista. » Ho sbagliato secolo E' un disco pacato, con alcuni gioiellini e altre canzoni che vanno ascoltate più volte per essere apprezzate nella » Shag’s Airport loro "normalità". » Blues, Blues e ancora Blues » Accordiamoci » Il leone nell’Arena » Francesco Garolfi: Un posto nel Non c'è niente di travolgente: sono le canzoni ironicamente rabbiose o serenamente mondo auliche di un uomo che aveva raggiunto la serenità fuori dal rutilante mondo dello star-system ma che continuava a » Alberto Tava: il nuovo disco pagare un pesante tributo agli anni passati con i Beatles (basti pensare all'accoltellamento subito da un pazzo che Mediterraneo tentava di ripetere il "caso" Lennon). » Il matrimonio che vorrei: da oggi a Pavia Nell'album ci sono 11 canzoni nuove e la cover di un vecchio brano (Between the Devil and the Deep Blue See). -

Sergeant Tapped for Chief's Post Be Students Planning Hoyts Boycott

••• _ .' •• ~' ••• L : ..... ~.j., ...... J"Jo.~.t..." r .. ·, ",:" -. • '0. • ~~1"""""'" _B~HLfHEM'PUBl-'-C' ~mRM?Y} 1 f DEC 1 P L'"fl 8490 1~~!03!9j SM BETHLEHEM F'tJ8LIC LI8RARY .451 [lEl.AWARE AVE lJEl_MAR NY 12054 Vol. XXXV No. ."",.inn the of Bethlehem and New Scotland Sergeant tapped for chief's post 28-year veteran ofBethlehem force to be sworn in Jd,n. 1 By Susan Wh,eeler said he was surprised to hear of his air Bethlehem Police Sgt. Richard pointment. "It's a good feeling,· said the laChappelle, a 23-year veteran of the midnight shift patrol sergeant. force, Monday was appointed as "The town is very fortunate to have Bethlehem's chief of police. had so many Qualified candidates within "Wewereimpressedwithallthecandi the department from which to choose," dates from inside the depa;.tment for this laChappelle said. "Many of the candi job. 1t was not an easy decision to make," datescouldhavefilledin {as chief) equally Supervisor Ken Ringler said. "The board as well." reached a consensus on Dick. He1l do a , , wonderful job." The Delmar resident began in the The search committee received eight department in 1968 as a narcotics officer. applications, four of which were from He was later appointed to detective, and Bethlehem Police Department employ detective supervisor. In the 1970s he was ees. Lieutenants Frederick HOlligan and made sergeant. As inspector from 1977 to Richard Vanderbilt, as well as sergeants 1983, laChappelle was second in com· Joseph Sleurs and laChappe!le submit Richard LaChappelle mand of the department. He has served ted resu mes_ All went through a final as midnight shift patrol sergeant since interview with the entire town board tee decided there were "several Qualified 1983. -

Danny Elfman's Music from the Films of Tim Burton

Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 6 –12 Avery Fisher Hall Danny Elfma n’s Music from the Films of Tim Burton Music Composed and Arranged by Danny Elfman Films and Artwork by Tim Burton Special Guest Performer Danny Elfman Conductor John Mauceri Violin Soloist Sandy Cameron Boy Sopranos John-Dominick Mignardi, Leif Christian Pedersen Philharmonia Orchestra of New York Concert Chorale of New York Approximate performance time: 2 hours 20 minutes, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 DANNY ELFMAN’S MUSIC FROM THE FILMS OF TIM BURTON Danny and Tim, without doubt, are the two greatest gifts this job ever gave me. I would be neither here, there, nor probably anywhere without them and their general magnificence. Now, the world is fully aware of the individual genius to be found betwixt the two, but what is more important here is the way in which these unique talents combine and ulti - mately complement one another, allowing the other’s work to bloom in a way unfore - seen independently. Essentially, Danny’s darkly sonorous creations are the audio manifestations of Tim’s sin - gularly shadowy visions. He is the Ralph Steadman to Tim’s Hunter S. -

RUSSELL CROWE ELIZABETH BANKS E LIAM NEESON OLIVIA WILDE

RUSSELL CROWE ELIZABETH BANKS e LIAM NEESON OLIVIA WILDE Regia di PAUL HAGGIS Durata: 122’ Uscita: 8 Aprile Ufficio Stampa Medusa Maria Teresa Ugolini Via Aurelia Antica 422/424 Alessandro Russo 00165 – Roma, Italia Via Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, 47 phone: +39 06 66390.640 00193 – Roma, Italia fax: +39 06 66390.567 phone: +39 06 916507804 e-mail: www.alerusso.it [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] CAST PERSONAGGI Russell Crowe John Brennan Elizabeth Banks Lara Brennan Brian Dennehy George Brennan Lennie James Lieutenant Nabulsi Olivia Wilde Nicole Ty Simpkins Luke Helen Carey Grace Brennan e con Liam Neeson Damon Pennington Daniel Stern Meyer Fisk Kevin Corrigan Alex Jason Beghe Detective Quinn Aisha Hinds Detective Collero Tyrone Giordano Mike Jonathan Tucker David Allan Steele Sergeant Harris RZA Mouss Moran Atias Erit Michael Buie Mick Brennan CAST TECNICO Regia & Sceneggiatura di Paul Haggis Prodotto da Michael Nozik Paul Haggis Prodotto da Olivier Delbosc Marc Missonnier Produttori Esecutivi Agnes Mentre Anthony Katagas Direttore della Fotografia Stéphane Fontaine, A.F.C. Scenografie Laurence Bennett Montaggio di Jo Francis Costumi di Abigail Murray Musiche di Danny Elfman Direttore del Casting Randi Hiller Co-Produttore Eugenie Grandval Basato sul film 'Pour Elle', diretto da Fred Cavayé e sceneggiato da Fred Cavayé e Guillaume Lemans The Next Three Days – Note sulla Produzione | 2 SINOSSI La vita di John Brennan (Russell Crowe) sembra perfetta fino a quando sua moglie, Lara (Elizabeth Banks), viene arrestata e condannata per un omicidio che sostiene di non aver commesso. A tre anni dalla condanna, John continua a battersi per tenere unita la famiglia, a crescere il loro unico figlio, Luke (Ty Simpkins) e a svolgere il suo lavoro di insegnate in un college pubblico, tentando sempre di dimostrare l‟innocenza della moglie con ogni mezzo a disposizione. -

Chris Aguilar-Garcia

Conference Speakers and Abstracts Chris Aguilar-Garcia Independent Scholar, USA Chris Aguilar-Garcia worships in the name of Madonna, Prince, and the Holy Spirit (Wendy and Lisa). He fell into fandom upon purchasing Prince's “1999” in 1982 and realised a lifelong dream when hired as a video editor at Paisley Park in 2001. Currently completing a BA at Antioch University-Los Angeles in Liberal Studies and Queer Studies, Chris is a Queer, male-bodied person who also worked as a film producer assistant, Program Manager at an LGBTQ scholarship organization, and currently in a public library. He counts sharing a spin class with Her Madgesty as a religious experience and life high point. New Power, Sexuality and Emancipation: The revolutionary queerness of Prince through a Foucauldian lens. From arriving on the 1980’s music scene in bikini briefs, eyeliner and high heels, singing songs about incest and masturbation, to a fight for emancipation from recording industry contracts, Prince consistently held the power dynamics of sexuality and domination as key to liberation from the binds of what French philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault termed ‘government of individualization’. Prince demonstrated his full-throttled approach to creating art not only as objects in the form of music, motion pictures, and videos, but as a mindful daily practice of living art and resistance. Prince’s vibrant life force enlivened Foucault’s belief that, “we should not have to refer the creative activity of somebody to the kind of relation he has to himself, but should relate the kind of relation one has to oneself to a creative activity.” For Prince, power also derived from his refusal to conform -- demanding to produce his debut album, creating side projects as additional creative outlets, changing his name to a symbol, and creating a pioneering web- distribution platform. -

Alice-In-Wonderland-Production-Notes.Pdf

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.wdsfilmpr.com © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. disney.com/wonderland Casting by. SUSIE FIGGIS Unit Production CREDITS WALT DISNEY PICTURES Managers . THOMAS HARPER PETER TOBYANSEN Presents First Assistant ALICE IN Director . KATTERLI FRAUENFELDER Second Assistant WONDERLAND Director . BRANDON LAMBDIN A Associate Producer . DEREK FREY ROTH FILMS Visual Effects Producer. TOM PEITZMAN Production Visual Effects Supervisors . SEAN PHILLIPS A CAREY VILLEGAS TEAM TODD Animation Supervisor . DAVID SCHAUB Production Senior Visual Effects Producer . CRYS FORSYTH-SMITH A Conceptual Designs by . DERMOT POWER ZANUCK COMPANY Production CAST A Film by Mad Hatter . JOHNNY DEPP TIM BURTON Alice . MIA WASIKOWSKA Red Queen . HELENA BONHAM CARTER White Queen . ANNE HATHAWAY Directed by . TIM BURTON Stayne – Knave of Hearts. CRISPIN GLOVER Screenplay by . LINDA WOOLVERTON Tweedledee/Tweedledum . MATT LUCAS Based on “ALICE’S ADVENTURES White Rabbit . MICHAEL SHEEN IN WONDERLAND” and Cheshire Cat . STEPHEN FRY “THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS” Blue Caterpillar . ALAN RICKMAN by. LEWIS CARROLL Dormouse . BARBARA WINDSOR Produced by . RICHARD D. ZANUCK March Hare . PAUL WHITEHOUSE Produced by . SUZANNE TODD Bayard . TIMOTHY SPALL & JENNIFER TODD Charles Kingsleigh . MARTON CSOKAS Produced by . JOE ROTH Lord Ascot. TIM PIGOTT-SMITH Executive Producers. PETER TOBYANSEN Colleague #1 . JOHN SURMAN CHRIS LEBENZON Colleague #2 . PETER MATTINSON Co-Producers . KATTERLI FRAUENFELDER Helen Kingsleigh . LINDSAY DUNCAN TOM PEITZMAN Lady Ascot . GERALDINE JAMES Director of Hamish. LEO BILL Photography. DARIUSZ WOLSKI, ASC Aunt Imogene . FRANCES DE LA TOUR Production Designer. ROBERT STROMBERG Margaret Kingsleigh. JEMMA POWELL Film Editor . CHRIS LEBENZON, A.C.E. Lowell. JOHN HOPKINS Costume Designer. COLLEEN ATWOOD Faith Chattaway .