Mexican National Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spa 248/Flm 495 Mexican Culture Through Film

SPA 248/FLM 495 MEXICAN CULTURE THROUGH FILM Course location: Cuernavaca, Mexico with excursions to Mexico City Fall semester only Prerequisites: for SPA 248: SPA 111 or instructor’s permission; for FLM 495: none. Course Description Welcome to SPA 248/FLM 495! This course is designed for both language learners and film Students with an interest in Mexican Cinema and Cultures. Both intermediate Spanish language learners and beginning Spanish language learners will develop their film and language literacy through the lens of Mexican filmmaking. The course may be taken in Spanish or in English, and course materials will be taught and offered in both Spanish and English to include a range of language comprehension. The course counts as an elective toward the Spanish major and minor, as well as a Film Studies and Communication Studies elective. The course will present a wide range of Mexican films from the Mexican Golden Age of Cinema “Cine de Oro” to the contemporary documentary auteur revolution. Films will feature diverse cast of characters including: Malinche, El Santo of Lucha Libre, Frida Kahlo, Yalitzia Aparacio, Cantinflas, Pedro Infante, Emilio “El Indo” Hernandez and Gael Garcia Bernal among many others. Course Objectives The course consists primarily of watching and discussing films in Spanish. The main objectives are: to provide an overview of the contemporary cinema of Mexico and the vocabulary to discuss it critically. to explore the cultural and historical dimensions of Mexican film and understand the major differences between the latter and the mainstream American film industry. to appreciate the complexity of Mexican cultures through the analysis of Mexican films. -

La Frontera- the US Border Reflected in the Cinematic Lens David R

1 La Frontera- The U.S. Border Reflected in the Cinematic Lens David R. Maciel1 Introduction The U.S.-Mexico border/la frontera has the distinction of being the only place in the world where a highly developed country and a developing one meet and interact.2 This is an area of historical conflict, convergence, conflict, dependency, and interdependency, all types of transboundary links, as well as a society of astounding complexity and an evolving and extraordinarily rich culture. Distinct border styles of music, literature, art, media, and certainly visual practices have flourished in the region. Several of the most important cultural and artistic-oriented institutions, such as universities, research institutes, community centers, and museums are found in the border states of both countries. Beginning in the late 19th century and all the way to the present certain journalists, writers and visual artists have presented a distorted vision of the U.S. - Mexican border. The borderlands have been portrayed mostly as a lawless, rugged, and perilous area populated by settlers who sought a new life in the last frontier, but also criminals and crime fighters whose deeds became legendary. As Gordon W. Allport stated: 1 Emeritus Professor, University of New Mexico. Currently is Adjunct Professor at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico City. 2 Paul Ganster and Alan Sweedler. The United States-Mexico Border Region: Implications for U.S. Security. Claremont CA: The Keck Center for International Strategic Studies, 1988. 2 [Stereotypes] aid people in simplifying their categories; they justify hostility; sometimes they serve as projection screens for our personal conflict. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

List of Films Considered the Best

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This list needs additional citations for verification. Please Contents help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Featured content Current events Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November Random article 2008) Donate to Wikipedia Wikimedia Shop While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications and organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned Interaction in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources Help About Wikipedia focus on American films or were polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the Community portal greatest within their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely considered Recent changes among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list or not. For example, Contact page many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best movie ever made, and it appears as #1 Tools on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawshank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst What links here Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. Related changes None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientific measure of the Upload file Special pages film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stacking or skewed demographics. -

Acevedo-Muñoz 1 Los Olvidados

Acevedo-Muñoz 1 Los olvidados: Luis Buñuel and the Crisis of Nationalism in Mexican Cinema by Ernesto R. Acevedo-Muñoz The University of Iowa Prepared for delivery at the 1997 meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, Continental Plaza Hotel, Guadalajara, Mexico April 17-19, 1997 Acevedo-Muñoz 2 Los olvidados: Luis Buñuel and the Crisis of Nationalism in Mexican Cinema The release of Los olvidados in 1950 is one of the historical markers of what I call the “crisis of nationalism” in Mexican cinema. The film was widely received as the “return” of Buñuel by European critics after the period of unnoticeable activity between 1932, the year of Las Hurdes, and 1946, the year of Buñuel’s incorporation into Mexican cinema and of the production of Gran Casino, which led to Buñuel’s Mexican career of almost twenty years and almost twenty movies. Nevertheless, it is known that at the time of the premiere of Los olvidados in Mexico City (November 9, 1950) the movie was mainly taken as an insult to Mexican sensibilities and to the Mexican nation. The stories of the detractors of Los olvidados are, of course, many and well documented.1 As it was often to be the case with Buñuel’s Mexican period, it took for Los olvidados to gather some prestige abroad before it was welcome in Mexico City. After its triumph at Cannes, where Buñuel won the best director award, Los olvidados had a successful season in a first run theater. Acevedo-Muñoz 3 Buñuel’s relationship with Mexican cinema went through several different stages, but it is significant that Los olvidados is recognized both by international critics and Mexican film historians as the turning point in the director’s entire career. -

Carolyn Fornoff

CAROLYN FORNOFF Department of Spanish & Portuguese University of Pennsylvania 521 Williams Hall 255 South 36th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6304 [email protected] 512.917.8129 EDUCATION: Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, Spanish & Portuguese, expected February 2017. M.A., University of Pennsylvania, Spanish & Portuguese, December 2012. B.A., Rice University, Hispanic Studies, magna cum laude, May 2008. Dissertation: “Species Sadness: Sex, Politics, and Nonhuman Creativity in Latin America” Committee: Román de la Campa (Chair), Marie Escalante, Jorge Téllez, & Beatriz González-Stephan RESEARCH AND TEACHING FIELDS: • Mexican Studies • Central American Studies • 20th- and 21st-Century Literature and Poetry • Film Studies • Ecocriticism and Animal Studies • Gender and Queer Theory • Affect Theory PUBLICATIONS: Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles “Passivity and Nonhuman Absorption in Julieta Campos’s “Celina o los gatos”.” Revista de Estudios Hispánicos. (Forthcoming, 2017) “Ernesto Cardenal’s Apologia for Ezra Pound.” Istmo: Revista de estudios literarios y culturales centroamericanos, vol. 32, 2016. (Forthcoming) “Descifrar el Secreto: “La secta del Fénix” y el acertijo literario”. Variaciones Borges, vol. 39, 2015, pp. 125-142. Book Chapters González-Stephan, Beatriz and Carolyn Fornoff, “Market and Non-Consumer Narratives: From the Levity of Being to Abjection.” The Cambridge History of Latin American Women’s Literature, edited by Ileana Rodríguez and Mónica Szurmuk, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 486-503. Other Publications Scholarly Dictionary Entries: The Fugitive (Film, 1947); Border Incident (Film, 1949); El norte (Film, 1983); Girlfight (Film, 2000). Race and Ethnicity in American Film: The Complete Resource. Edited by Daniel L. Bernardi and Michael Green, ABC-CLIO/Greenwood. (Forthcoming, June 2017) Fornoff 2 Review of Cortázar Sampleado, edited by Pablo Brescia. -

Hegemony and Mediations in Melodrama of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema

HEGEMONY AND MEDIATIONS IN MELODRAMA OF THE GOLDEN AGE OF MEXICAN CINEMA By Dave Evans A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Spanish and Latin American Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2015 ABSTRACT The influence of the mass media is a contentious issue, especially in regards to the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema in the mid-twentieth century. These melodramatic films have often been viewed by critics as instruments of hegemony. However, melodrama contains an inherent ambivalence, as it not only has a potential for imparting dominant messages but also offers a platform from which to defy and exceed the restraining boundaries imposed by dominant ideologies. An examination of a number of important Golden Age films, especially focussing on their contradictory tensions and their portrayals of modernity, illustrates this. The Nosotros los pobres series serves as an example of how melodramatic elements are incorporated into popular Mexican films and how melodrama could be used as an ideological tool to encourage the state’s goals. Similarly, the maternal melodrama Cuando los hijos se van uses the family to represent the processes of conflict and negotiation that Mexicans experienced as a result of modernization. Consistent with the reactionary nature of melodrama and its simultaneous suggestive potential, the film combines a Catholic worldview with an underlying allegory of moving forward. The issue of progress is also at the centre of a number of films starring iconic actor Pedro Infante, which offer an avenue for exploring what modernisation might mean for male identity in Mexico. -

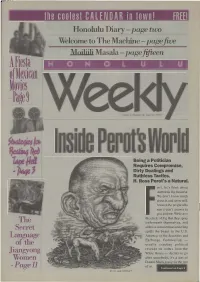

I He CD DI Es I CALE N DAR in ID W N I Freei

I he CDDI es I CALE N DAR in ID w n I FREEi HonoluluDiary- pagetwo Welcome to The Machine-pagefive Moi]ii]i Masala- pagefifteen AFiesra of Mexican Movies -�ge� Being a Politician RequiresCompromise, Dirty Dealings and Ruthless Tactics. H. Ross Perot'sa Natural. irst, let's think about American big business. We don't know much about it, and never will, because the people who run it don't answer to you and me. We live in the circle of fog that they spray The underneath themselves, and unless a conscientious underling Secret spills the beans to the U.S. Lfil!gl_lage �®,-· Attorney, or the Securities and Exchange Commission - of the usually exacting political revenge on orders from the J�ong White House - decides to go Wollle after somebody, it's a diet of n Donald-Marla gossip forthe rest of us. -Pagell Continued on Page 6 @ 1qq1 JOHii! S. PRITCHETT Art Kazu Hayashida, the Board's man Honey Alexander, wifeof Bush's ager and chief engineer. The Board's Education Secretary, Lamar On June 21, the annual American announcement did not indicate the Alexander, was elected vice-chair Civil Liberties Union awards dinner cost of the study. person ... Hawaii County's popula will have a most interesting keynote tion is growing 2.5 times faster than speaker - former National the national average and Maui's is Endowment for the Arts chairper Sex growing at three times the national son John Frohnmayer. Forced out by According to American rate ... Hawaii has the fourth highest George Bush in a flap catalyzed by Demographics magazine, some old rate of state and local tax revenue Pat Buchanan's threat to make the sexual notions have recently been per $100 of personal income - NEA's fundingof "controversial"art confirmed, and some new discover $14.21. -

The Contemporary Body of Mexican Masculinities A

THE CONTEMPORARY BODY OF MEXICAN MASCULINITIES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Samanta Ordóñez Robles August 2015 © 2015 Samanta Ordóñez Robles THE CONTEMPORARY BODY OF MEXICAN MASCULINITIES Samanta Ordóñez Robles, Ph.D. Cornell University 2015 Abstract: This dissertation thematizes masculinity in Mexico’s post-NAFTA configurations of subjectivities and bodies, and in the geocultural politics of race and gender in order to analyze how male identities are produced and reified within these intersecting structures of oppression. It encompasses questions of resistance, gender categories established by nationalism and late capitalism, and modern/colonial power relations. I explore cinematic and literary engagements with maleness in order to demonstrate how collusion between neoliberal economic interests and the state’s established political and cultural framework of power conceals the deployment of gendered concepts of citizenship and subjectivity as a mechanism to exercise control over Mexican bodies. I conceptualize this process in terms of a violent colonial strategy of subjection which coerces men to internalize normative codes of masculinity based on essentialist categories of race, sexuality, biological sex, and space. I address relevant scholarly debates in postcolonial studies and discussions of neoliberalism’s impact on culture, politics and identity. In my first chapter, I examine patriotic male performances in northern Mexico as portrayed in the novels Duelo por Miguel Pruneda (2002) and El ejército iluminado (2006) by David Toscana. I posit that through their efforts to overcome U.S. imperialism northern males in these texts are revealed as dominated subjects for whom national masculinity is a failing model for resistance. -

Performing Arts Annual 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 301 906 C3 506 492 AUTHOR Newsom, Iris, Ed. TITLE Performing Arts Annual 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0570-1; ISBN-0887-8234 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 189p. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 (Ztock No. 030-001-00120-2, $21.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Activities; *Dance; *Film Industry; *Films; Music; *Television; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress; *Screenwriters ABSTRACT Liberally illustrated with photographs and drawings, this book is comprised of articles on the history of the performing arts at the Library of Congress. The articles, listed with their authors, are (1) "Stranger in Paradise: The Writer in Hollywood" (Virginia M. Clark); (2) "Live Television Is Alive and Well at the Library of Congress" (Robert Saudek); (3) "Color and Music and Movement: The Federal Theatre Project Lives on in the Pages of Its Production Bulletins" (Ruth B. Kerns);(4) "A Gift of Love through Music: The Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge" (Elise K. Kirk); (5) "Ballet for Martha: The Commissioning of 'Appalachian Spring" (Wayne D. Shirley); (6) "With Villa North of the Border--On Location" (Aurelio de los Reyes); and (7) "All the Presidents' Movies" (Karen Jaehne). Performances at the library during the 1986-87season, research facilities, and performing arts publications of the library are also covered. (MS) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. 1 U $ DEPARTMENT OP EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement 411.111.... -

Adán Ávalos CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected]

Adán Ávalos CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. 2012 University of Southern California, School of Cinematic Arts Critical Studies M.A. 2006 University of Southern California, School of Cinematic Arts Critical Studies Teaching 1998 California State University, Fresno, College of Education Credential Single Subject, Art B.A. 1997 California State University, Fresno, College of Art & Design Art B.A. 1997 California State University, Fresno, College of Social Science Chicano and Latin American Studies TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2014–Present Assistant Professor, Latin American and U.S. Latina/o Film University of New Mexico, Cinematic Arts Department Courses: Film Theory, Latin American Cinema: Theories of Resistance, International Cinema, Mexican Cinema, Beyond Hollywood: Cinema of Childhood, Media and Social Change: Production 2013–2014 Artistic Director/Lecturer, Center for Creativity and the Arts California State University, Fresno, Department of Art & Design, Department of Mass Communication & Journalism Courses: Art Appreciation, Art 102: Visual Literacy, Middle Eastern Cinema 2012–2013 Lecturer, Chicano Latin American Studies California State University, Fresno, Dept. of Chicano Latin American Studies Courses: Chicano Artistic Expression, Critical Thinking, Online Course 2011–2012 Assistant Professor, Screen Studies Red Sea Institute of Cinematic Arts, Aqaba, Jordan Courses: Critical Approaches to Cinema, International Cinema, Film Theory, Middle Eastern Cinema, Film Production Workshop Ávalos | 1 2010–2011 Media Instructor, Mary -

Why Is Latin American Cinema So Under- Represented At

Argentina (htt(ph:t/t(/pht:wt/t(/iphwt:t/wte/prww.:c/w.o/ffawmece.e/sdsboosou.usonnokdud.cnslocodmouslda/osn.ucodoruscmn/o)d/lossouaunrsnd.cdcoosmalon/udsrocsou)lnodusrasn/)dcolours) (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/argentina) Like 2.8k (HTTP://WWW.SOUBoNliviaDSANDCOLOURS.COM/) Home (http://www.soundsandcolours.com) News (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/news) Music (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/music) Film (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/film) Books (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/books) What’s On (http://www.soundsWandcoHloursY.com /IevSent ) LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA SO UNDER- Bandcamp (http://soundsandcRolouErs.bPandRcamEp.coSm/E) NTED AT CANNES? Subscribe By Nick MacWilliam (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/author/nick/) - 15 May, 2013 (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/subscribe/) Tw eet 10 5 Me gusta 46 About (http://www.soundsandcolours.com/about/) The representation of Latin American cinema at the Cannes Film Festival (http://www.festival- cannes.fr/) has, since the festival’s inception in 1939, been about as visible as a contact lens in the bath. In spite of the strong cinematic heritage of Brazil and Cuba in the mid- to late- twentieth century, and more latterly the film industries of Peru, Chile and Argentina, Cannes and the other big players on the international festival circuit have tended to look to their European heartland, the United States, or eastwards across Asia when it comes to defining their content and giving out the gongs. In the entire history of the festival, the only Latin American winners of the highest honour, the Palme d’Or, were way back when. The Mexican director Emilio Fernández’s film Portrait of Maria was the first in 1946 but this award was shared with ten other films at the first festival after the Second World War.