Luke 16: 1-8A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luke 16:19-31)

“A Final Word from Hell” (Luke 16:19-31) If you’ve ever flown on an airplane you’ve probably noticed that in the seat pocket ahead of you is a little safety information card. It contains lots of pictures and useful information illustrating what you should do if, for example, the plane you’re entrusting your life with should have to ditch in the ocean. Not exactly the kind of information most people look forward to reading as they’re preparing for a long flight. The next time you’re on an airplane, look around and see how many people you can spot actually reading the safety cards. Nowadays, I suspect you’ll find more people talking or reading their newspaper instead. But suppose you had a reason to believe that there was a problem with the flight you were on. Suddenly, the information on that card would be of critical importance—what seemed so unimportant before takeoff could mean the difference between life and death. In the same way, the information in the pages of God’s Word is critically important. The Bible contains a message that means the difference between eternal life and death. Yet, for many of us, our commitment to the Bible is more verbal than actual. We affirm that the Bible is God’s Word, yet we do not read it or study it as if God was directly communicating to us. If left with a choice, many of us would prefer to read the newspaper or watch TV. Why is this? Certainly one reason for this is that there is not a sense of urgency in our lives. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Outcasts (5): Blessed Are the Poor (Luke 6:20-26) I

Outcasts (5): Blessed Are the Poor (Luke 6:20-26) I. Introduction A. We continue today with “Outcasts: Meeting People Jesus Met in Luke” 1. Luke has a definite interest in people on the-outside-looking-in a. His birth narrative tells of shepherds, the mistrusted drifter-gypsies b. Later she shows Jesus touched lepers, ultimate of aunclean outcasts c. He mentions tax collectors more than Matthew and Mark combined 2. The outcast we will look at today from Luke’s gospel is the poor a. Jesus first sermon in Luke was a text on the poor (Luke 4:18-19) b. John asks from prison if Jesus is really Messiah (Luke 7:22-23) c. Jesus is asked about handwashing & ritual purity (Luke 11:39-40) d. Jesus proclaims his own solidarity with the poor (Luke 9:58) e. Jesus equates the kingdom with giving to poor (Luke 12:32-34) 3. Jesus had quite a lot to say about the poor in Luke (see more later) a. Were some of those text just a little bit unfamiliar to us? Why? b. What first pops into our head when we think of helping the poor c. Did you think Bernie Sanders and “Liberal Democratic Socialism?” 1) Political Test: The difference between socialism and capitalism 2) Socialism is man exploiting man. Capitalism is other way around 3) Jesus doesn’t care about our politics; he wants us to care about poor B. Our “outcast” Jesus encounters will be quite different this morning 1. Jesus doesn’t run into a poor person; he stood and teach (Luke 6:17) a. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Week 1 Readings “Introduction”

COMPASS CATHOLIC FINANCIAL BIBLE STUDY “THE VERSES” COMPASS CATHOLIC MINISTRIES 1 FINANCIAL BIBLE STUDY Week 1 Readings “Introduction” Memory Verse: Luke 16:11 (This verse is the Compass theme.) “Therefore, if you have not been faithful in the use of worldly wealth, who will entrust the true riches to you?” Questions 3-5: Isaiah 55: 8-9 “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor your ways my ways, says the Lord.” Week 2 Readings “God‟s Part / Our Part” 2 Memory Verse: 1 Chronicles 29:11-12 “Everything in the heavens and earth is yours O Lord, and this is your kingdom. We adore you as being in control of all things. Riches and honor come from you alone, and it is at your discretion that people are made great and given strength.” Day One Question 3: Deuteronomy 10:14 “Behold, to the Lord your God belong the highest heavens, the earth and all that is in it.” Psalm 24: 1 “The earth is the Lord‟s and all it contains; even all who dwell in it.” 1 Corinthians 10: 26 “For the earth is the Lord‟s and all it contains.” Question 4: Leviticus 25:23 “The land shall not be sold permanently, for the land is Mine; for you are aliens and sojourners with Me.” Psalm 50: 10-12 “For every beast of the forest is Mine; the cattle, the birds and everything that moves in the field is mine. The world is mine and all it contains.” Haggai 2:8 “The silver and gold are mine, declares the Lord of Hosts.” Day Two (week 2): 3 Question 1: 1 Chronicles 29:11-12 (memory verse) “Everything in the heavens and earth is yours O Lord, and this is your kingdom. -

The Prodigal Father

"There was a man who had two sons..." - LUKE 15:11 THE PRODIGAL FATHER LUKE 15:11-24 NOVEMBER 29, 2020 TRADITIONAL SERVICE 10:30 AM TRADITIONAL WORSHIP SERVICE NOVEMBER 29 • THE FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT Welcome! Are you new at Christ Church? Please stop by our Welcome Welcome to worship. To care for one another, we ask that those seated in the mask-only section keep their face Table in the Gathering Hall or coverings on throughout the service, and we are refraining from singing aloud during this season. Children may Family Life Center Lobby to pick up a take-home activity packet on the tree in the landing for use in worship and afterwards. learn more about our church and how to get involved. Worship with us safely outdoors at Constellation Field on Christmas Eve! All are invited to stay afterward and enjoy the Holiday Lights as our guests. PRELUDE DOXOLOGY We offer two worship services Masks will be required as you enter and exit. Space is limited! Bring a Torch, Jeanette, Isabella Angels We Have Heard On High each Sunday morning, both at We will also worship in our Sanctuary at 12 pm and 8 pm on Christmas Eve. arr. Heather Sorenson 10:30 am. Preaching today are: Seating will be limited, and masks will be required for the indoor services. BETH McCONNELL SCRIPTURE READING TRADITIONAL SERVICE IN THE SANCTUARY Reserve your seats for our Christmas Eve services at christchurchsl.org/christmas. Luke 15:11-24 *GREETING & LIGHTING OF Pastor R. Deandre Johnson THE ADVENT CANDLE CONTEMPORARY SERVICE OUR ADVENT SERMON SERIES: SERMON IN COVENANT HALL *OPENING HYMNS "The Prodigal Son" Pastor C. -

Orthros on Sunday, February February February 28, 2016; Tone 6 / Eothinon 6 Sunday of the Prodigal Son Sunday of the Prodigal So

Orthros ononon SundaySunday,, February 22282888,, 2012016666;; Tone 666 / Eothinon 666 Sunday of the Prodigal Son Venerable Basil the Confessor, companion of Prokopios of Decapolis; Hieromartyr Proterios, archbishop of Alexandria; Righteous Kyra and Marana of Beroea in Syria; Apostles Nymphas and Euvoulos; New-martyr Kyranna of Thessalonica Priest: Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Choir: Amen. People: Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal: have mercy on us. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen. All-holy Trinity, have mercy on us. Lord, cleanse us from our sins. Master, pardon our iniquities. Holy God, visit and heal our infirmities for Thy Name’s sake. Lord, have mercy. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen. Our Father, Who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy Name. Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as it is in Heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us, and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Priest: For Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit; now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Choir: Amen. (Choir continues.) O Lord, save Thy people and bless Thine inheritance, granting to Thy people victory over all their enemies, and by the power of Thy Cross preserving Thy commonwealth. -

The Social World of Luke-Acts 1

RLNT770: History of NT Interpretation II The Social World of Luke-Acts 1 The Social World of Luke-Acts: Models for Interpretation, ed. Jerome H. Neyrey Annotated Outline by Elizabeth Shively for RLNT770 PREFACE Jerome H. Neyrey 1.0 Authors-Collaborators • This book results from the 1986 decision of a group of historical-critical scholars to apply social sciences to the biblical text. • They took a “systems approach” that seeks to understand a larger framework, i.e., the culture of those who produced the text. 2.0 Luke-Acts • Luke-Acts is good for the application of social sciences because of its concern with social aspects of the gospel, its geographical and chronological scope, and because of its universal issues. • The models applied to Luke-Acts can be applied to other NT documents. 3.0 A Different Kind of Book • The aim of the book is to decipher the meaning of Luke-Acts in and through the 1st c. Mediterranean social context, and to understand how this context shaped the author’s perspective, message and writing. • To do this, one must recognize the cultural distance between original and present readers; and read the text through a foreign model of the way the world works. • This book is meant to be a handbook of “basic social scientific perspectives” (xi) for historical-critical study. 4.0 Social Sciences and Historical Criticism • Rather than taking a purely historical approach, this book investigates the social and cultural patterns that shaped those who heard or read Luke-Acts. • Whereas history looks for a linear storyline, social science looks for typical repeated social patterns in specific times and places in order to find particular and distinctive perception and behavior. -

The Parable of the Prodigal Son

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary 10-2004 The Parable of the Prodigal Son Karen P. Sames OSB College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sames, Karen P. OSB, "The Parable of the Prodigal Son" (2004). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 18. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/18 This Graduate Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Parable of the Prodigal Son by S. Karen P. Sames, OSB 2675 E. Larpenteur Avenue St. Paul, MN 55109-5097 A Paper Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology. SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota October 2004 This paper was written under the direction of Signature of Director Dr. Charles A. Bobertz, Ph. D. 1 The Parable of the Prodigal Son This project began with the investigation of the role of parables in the teachings of Jesus Christ. I researched the function of parables and the different levels of interpretation. -

Luke 16:1-13 Jesus on Money: Making Friends with Unrighteous Money

LUKE 16:1-13 JESUS ON MONEY: MAKING FRIENDS WITH UNRIGHTEOUS MONEY “Jesus also said to the disciples, ‘There was a rich man who had a manager and charges were brought to him that this man was wasting his possessions. And he called him and said to him, “What is this that I hear about you? Turn in the account of your management, for you can no longer be manager.” And the manager said to himself, “What shall I do, since my master is taking the management away from me? I am not strong enough to dig, and I am ashamed to beg. I have decided what to do, so that when I am removed from management, people may receive me into their houses.” So, summoning his master’s debtors one by one, he said to the first, “How much do you owe my master?” He said, “A hundred measures of oil.” He said to him, “Take your bill, and sit down quickly and write fifty.” Then he said to another, “And how much do you owe?” He said, “A hundred measures of wheat.” He said to him, “Take your bill, and write eighty.” The master commended the dishonest manager for his shrewdness. For the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light. And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous wealth, so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal dwellings. “‘One who is faithful in a very little is also faithful in much, and one who is dishonest in a very little is also dishonest in much. -

Praying with Scripture

PRAYING WITH SCRIPTURE Cathedral of Mary of the Assumption 1 2 Praying with Scripture “The books of scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error the truth which God wanted to put in sacred writings for the sake of our salvation.” (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation) “All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness.” (2 Tim 2 18:17) “God's Word is alive and powerful, sharper than a two-edged sword.” (Hebrews 4:12) Lectio Divina This method of prayer goes back to the early monastic tradition. There were not bibles for everyone and not everyone knew how to read. So the monks gathered in chapel to hear a member of the community reading from the scripture. In this exercise they were taught and encouraged to listen with their hearts because it was the Word of God that they were hearing. When a person wants to use Lectio Divina as a prayer form today, the method is very simple. When one is a beginner, it is better to choose a passage from one of the Gospels or epistles, usually ten or fifteen verses. Some people who regularly engage in this method of prayer choose the epistle or the Gospel for the Mass of the day as suggested by the Catholic Church. First one goes to a quiet place and recalls that one is about to listen to the Word of God. Then one reads the scripture passage aloud to let oneself hear with his or her own ears the words. -

Scope and Sequence YEARS B-C Scope and Sequence

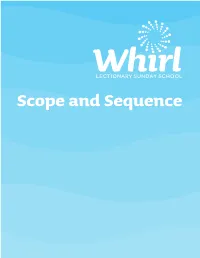

Scope and Sequence YEARS B-C Scope and Sequence FALL • YEAR B Season Sunday Date Lesson Title Focus Text Pentecost Lectionary 24 9/12/2021 Taming the Tongue James 3:1-12 Pentecost Lectionary 25 9/19/2021 Jesus Welcomes Children Mark 9:30-37 Pentecost Lectionary 26 9/26/2021 Pray for One Another James 5:13-20 Pentecost Lectionary 27 10/3/2021 Jesus Blesses Children Mark 10:2-16 Pentecost Lectionary 28 10/10/2021 A Camel through a Needle Mark 10:17-31 Pentecost Lectionary 29 10/17/2021 James and John Mark 10:35-45 Pentecost Lectionary 30 10/24/2021 Jesus Heals Bartimaeus Mark 10:46-52 Pentecost Lectionary 31 10/31/2021 The First Commandment Mark 12:28-34 Pentecost Lectionary 32 11/7/2021 The Widow’s Offering Mark 12:38-44 Pentecost Lectionary 33 11/14/2021 The Temple’s Destruction Mark 13:1-8 Pentecost Christ the King 11/21/2021 Pilate Accuses Jesus John 18:33-37 WINTER • YEAR C Season Sunday Date Lesson Title Focus Text Advent Advent 1 11/28/2021 Paul’s First Letter 1 Thessalonians 3:9-13 Advent Advent 2 12/5/2021 Malachi the Messenger Malachi 3:1-4 Advent Advent 3 12/12/2021 Zephaniah’s Joyful Song Zephaniah 3:14-20 Advent Advent 4 12/19/2021 Mary Visits Elizabeth Luke 1:39-55 Christmas Christmas Day 12/25/2021 Jesus Is Born Luke 2:1-20 Christmas Christmas 1 12/26/2021 Young Jesus in the Temple Luke 2:41-52 Christmas Christmas 2 1/2/2022 A Comforting Message Jeremiah 31:7-14 Epiphany Baptism of the Lord 1/9/2022 John Baptizes Jesus Luke 3:15-17, 21-22 Epiphany Epiphany 2 1/16/2022 Water to Wine John 2:1-11 Epiphany Epiphany 3 1/23/2022