Budget Sufficiency for First Nations Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the First Nation Infrastructure Fund

Final Report Evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund Project Number: 1570-7/13066 April 2014 Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch Audit and Evaluation Sector Table of Contents List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... iv Management Response / Action Plan ........................................................................ viii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Program Profile ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Evaluation Methodology ....................................................................................... 1 2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing .......................................................................................... 1 2.2 Evaluation Issues ............................................................................................................. 1 2.3 Evaluation Methodology .................................................................................................. 1 2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance ............................................................... -

Volume 2: Baseline, Section 13: Traditional Land Use September 2011 Volume 2: Baseline Studies Frontier Project Section 13: Traditional Land Use

R1 R24 R23 R22 R21 R20 T113 R19 R18 R17 R16 Devil's Gate 220 R15 R14 R13 R12 R11 R10 R9 R8 R7 R6 R5 R4 R3 R2 R1 ! T112 Fort Chipewyan Allison Bay 219 T111 Dog Head 218 T110 Lake Claire ³ Chipewyan 201A T109 Chipewyan 201B T108 Old Fort 217 Chipewyan 201 T107 Maybelle River T106 Wildland Provincial Wood Buffalo National Park Park Alberta T105 Richardson River Dunes Wildland Athabasca Dunes Saskatchewan Provincial Park Ecological Reserve T104 Chipewyan 201F T103 Chipewyan 201G T102 T101 2888 T100 Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park T99 1661 850 Birch Mountains T98 Wildland Provincial Namur River Park 174A 33 2215 T97 94 2137 1716 T96 1060 Fort McKay 174C Namur Lake 174B 2457 239 1714 T95 21 400 965 2172 T94 ! Fort McKay 174D 1027 Fort McKay Marguerite River 2006 Wildland Provincial 879 T93 771 Park 772 2718 2926 2214 2925 T92 587 2297 2894 T91 T90 274 Whitemud Falls T89 65 !Fort McMurray Wildland Provincial Park T88 Clearwater 175 Clearwater River T87Traditional Land Provincial Park Fort McKay First Nation Gregoire Lake Provincial Park T86 Registered Fur Grand Rapids Anzac Management Area (RFMA) Wildland Provincial ! Gipsy Lake Wildland Park Provincial Park T85 Traditional Land Use Regional Study Area Gregoire Lake 176, T84 176A & 176B Traditional Land Use Local Study Area T83 ST63 ! Municipality T82 Highway Stony Mountain Township Wildland Provincial T81 Park Watercourse T80 Waterbody Cowper Lake 194A I.R. Janvier 194 T79 Wabasca 166 Provincial Park T78 National Park 0 15 30 45 T77 KILOMETRES 1:1,500,000 UTM Zone 12 NAD 83 T76 Date: 20110815 Author: CES Checked: DC File ID: 123510543-097 (Original page size: 8.5X11) Acknowledgements: Base data: AltaLIS. -

Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69A Cultural Effects Review

October 2013 SHELL CANADA ENERGY Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69a Cultural Effects Review Submitted to: Shell Canada Energy Project Number: 13-1346-0001 REPORT APPENDIX 7: JRP SIR 69a CULTURAL EFFECTS REVIEW Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Report Structure .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Overview of Findings ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Shell’s Approach to Community Engagement ..................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Shell’s Support for Cultural Initiatives .................................................................................................................. 7 1.6 Key Terms ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.1 Traditional Knowledge .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.2 Traditional -

Current Contact Information

Current Contact Information Tribal Chiefs Employment & North East Alberta Apprenticeship Xpressions Arts & Design Training Services Association Initiative West Phone: (780) 520-7780 17533--106 Avenue, Edmonton, AB 15 Nipewan Road, Lac La Biche, AB Phone: (780) 481-8585 Cell: (780) 520-7375 Fax: (780) 488-1367 Cell: (780) 520-7644 TCETSA - Small Urban Offce North East Alberta Apprenticeship St. Paul, AB Initiative East Phone: (780) 645-3363 6003 47 Ave, Bonnyville, AB Fax: (780) 645-3362 Cell: (780) 812-6672 TCETSA VISION STATEMENT To provide a collaborative forum for those committed to the success of First Nations people by exploring and creating opportunities for increased meaningful and sustainable workforce participation Beaver Lake Cree Nation Heart Lake First Nation Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 623-4549 Phone: (780) 623-2130 Fax: (780) 623-4523 Fax: (780) 623-3505 Beaver Lake Daycare Heart Lake Daycare Phone: (780) 623-3110 Phone: (780) 623-2833 Fax: (780) 623-4569 Fax: (780) 623-3505 Cold Lake First Nations Kehewin Cree Nation Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 594-7183 Ext. 230 Phone: (780) 826-7853 Fax: (780) 594-3577 Fax: (780) 826-2355 Yagole Daycare Kehew Awasis Daycare Phone: (780) 594-1536 Phone: (780) 826-1790 Fax (780) 594-1537 Fax: (780) 826-6984 Frog Lake First Nation Whitefsh Lake First Nation #128 Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 943-3737 Phone: (780) 636-7000 Fax: (780) 943-3966 Fax: (780) 636-3534 Lily Pad Daycare Whitefsh Daycare Phone: (780) 943-3300 Phone: (780) 636-2662 Fax: (780) 943-2011 Fax: (780) 636-3871 2 TCETSA | 2016-2017 Annual Report Our TREATY Model The TREATY Model All of our programs are designed around the TREATY Model process for the purpose of focusing on solutions. -

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Alberta Regional Roll-Up Report FINAL Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development January 2011 Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville, Ontario L9W 3R4 1-800-595-9149 www.neeganburnside.com National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Alberta Regional Roll-Up Report Final Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Prepared By: Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville ON L9W 3R4 Prepared for: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada January 2011 File No: FGY163080.4 The material in this report reflects best judgement in light of the information available at the time of preparation. Any use which a third party makes of this report, or any reliance on or decisions made based on it, are the responsibilities of such third parties. Neegan Burnside Ltd. accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report. Statement of Qualifications and Limitations for Regional Roll-Up Reports This regional roll-up report has been prepared by Neegan Burnside Ltd. and a team of sub- consultants (Consultant) for the benefit of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (Client). Regional summary reports have been prepared for the 8 regions, to facilitate planning and budgeting on both a regional and national level to address water and wastewater system deficiencies and needs. The material contained in this Regional Roll-Up report is: preliminary in nature, to allow for high level budgetary and risk planning to be completed by the Client on a national level. -

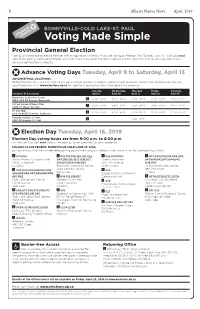

Voting Made Simple

8 Alberta Native News April, 2019 BONNYVILLE-COLD LAKE-ST. PAUL Voting Made Simple Provincial General Election Voting will take place to elect a Member of the Legislative Assembly. If you are voting on Election Day, Tuesday, April 16, 2019, you must vote at the polling station identified for you in the map. If you prefer to vote in advance, from April 9 to April 13, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance Voting Days Tuesday, April 9 to Saturday, April 13 ADVANCE POLL LOCATIONS Before Election Day, you may vote at any advance poll location in Alberta. Advance poll locations nearest your electoral division are specified below. Visit www.elections.ab.ca for additional polling locations throughout the province. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Advance Poll Location April 9 April 10 April 11 April 12 April 13 Bonnyville Centennial Centre 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 1003, 4313 50 Avenue, Bonnyville St.Paul Senior Citizens Club 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 4809 47 Street, St. Paul Tri City Mall 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM 9 AM - 8 PM Unit 20, 6503 51 Street, Cold Lake Portage College St. Paul 9 AM - 8 PM 5205 50 Avenue, St. Paul Election Day Tuesday, April 16, 2019 Election Day voting hours are from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

The Wealth of First Nations

The Wealth of First Nations Tom Flanagan Fraser Institute 2019 Copyright ©2019 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief passages quoted in critical articles and reviews. The author of this book has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, there- fore, his own and and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Board of Directors, its donors and supporters, or its staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data The Wealth of First Nations / by Tom Flanagan Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-533-8. Fraser Institute ◆ fraserinstitute.org Contents Preface / v introduction —Making and Taking / 3 Part ONE—making chapter one —The Community Well-Being Index / 9 chapter two —Governance / 19 chapter three —Property / 29 chapter four —Economics / 37 chapter five —Wrapping It Up / 45 chapter six —A Case Study—The Fort McKay First Nation / 57 Part two—taking chapter seven —Government Spending / 75 chapter eight —Specific Claims—Money / 93 chapter nine —Treaty Land Entitlement / 107 chapter ten —The Duty to Consult / 117 chapter eleven —Resource Revenue Sharing / 131 conclusion —Transfers and Off Ramps / 139 References / 143 about the author / 161 acknowledgments / 162 Publishing information / 163 Purpose, funding, & independence / 164 About the Fraser Institute / 165 Peer review / 166 Editorial Advisory Board / 167 fraserinstitute.org ◆ Fraser Institute Preface The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau elected in 2015 is attempting massive policy innovations in Indigenous affairs. -

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expension Project

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project November 2016 Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms, Abbreviations and Definitions Used in This Report ...................... xi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ..............................................................................1 1.2 Project Description .................................................................................2 1.3 Regulatory Review Including the Environmental Assessment Process .....................7 1.3.1 NEB REGULATORY REVIEW AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ....................7 1.3.2 BRITISH COLUMBIA’S ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................8 1.4 NEB Recommendation Report.....................................................................9 2. APPROACH TO CONSULTING ABORIGINAL GROUPS ........................... 12 2.1 Identification of Aboriginal Groups ............................................................. 12 2.2 Information Sources .............................................................................. 19 2.3 Consultation With Aboriginal Groups ........................................................... 20 2.3.1 PRINCIPLES INVOLVED IN ESTABLISHING THE DEPTH OF DUTY TO CONSULT AND IDENTIFYING THE EXTENT OF ACCOMMODATION ........................................ 24 2.3.2 PRELIMINARY -

Submission of Maskwacis Cree to the Expert Mechansim

SUBMISSION OF MASKWACIS CREE TO THE EXPERT MECHANSIM ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES STUDY ON THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES WITH A FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND YOUTH Contact: Danika Littlechild, Legal Counsel Maskwacis Cree Foundation PO Box 100, Maskwacis AB T0C 1N0 Tel: +1-780-585-3830 Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents SUBMISSION OF MASKWACIS CREE TO THE EXPERT MECHANSIM ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES STUDY ON THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES WITH A FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND YOUTH ........................ 1 Introduction and Summary ............................................................................................................. 3 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 The Tipi Model Approach ............................................................................................................. 11 Summary of the Tipi Model ..................................................................................................................... 12 Elements of the Tipi Model ..................................................................................................................... 14 Canadian Law, Policy and Standards ........................................................................................ 15 The Indian Act ............................................................................................................................................. -

Aboriginal Peoples of Alberta : Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

Aboriginal Peoples of Alberta Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Photograph: Top to bottom Albert and Alma Desjarlais, Aaron Paquette, Roseanne Supernault, Angela Gladue, and Victoria Callihoo As special thank you to all of the individuals who contributed to this booklet, as writers, as trusted advisors, and also to those who generously shared their voices with all Albertans. Contents Creating Understanding ......................................................................2 Chapter 9 Chapter 1 Métis people In the Beginning .............................................................................................4 Establishing a Métis Land Base in Alberta ...............30 Buffalo Lake ................................................................................................ 31 Chapter 2 East Prairie .................................................................................................... 31 Early Life ...................................................................................................................7 Elizabeth ........................................................................................................... 31 Chapter 3 Fishing Lake ............................................................................................... 31 Aboriginal Peoples ......................................................................................9 Gift Lake ........................................................................................................... 31 Chapter 4 Kikino ................................................................................................................. -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO.