CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Extended Technique and the Modern Flautist: a Comparison of Two Contemporary Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playing (With) Sound of the Animation of Digitized Sounds and Their Reenactment by Playful Scenarios in the Design of Interactive Audio Applications

Playing (with) Sound Of the Animation of Digitized Sounds and their Reenactment by Playful Scenarios in the Design of Interactive Audio Applications Dissertation by Norbert Schnell Submitted for the degree of Doktor der Philosophie Supervised by Prof. Gerhard Eckel Prof. Rolf Inge Godøy Institute of Electronic Music and Acoustics University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, Austria October 2013 Abstract Investigating sound and interaction, this dissertation has its foundations in over a decade of practice in the design of interactive audio applications and the development of software tools supporting this design practice. The concerned applications are sound installations, digital in- struments, games, and simulations. However, the principal contribution of this dissertation lies in the conceptualization of fundamental aspects in sound and interactions design with recorded sound and music. The first part of the dissertation introduces two key concepts, animation and reenactment, that inform the design of interactive audio applications. While the concept of animation allows for laying out a comprehensive cultural background that draws on influences from philosophy, science, and technology, reenactment is investigated as a concept in interaction design based on recorded sound materials. Even if rarely applied in design or engineering – or in the creative work with sound – the no- tion of animation connects sound and interaction design to a larger context of artistic practices, audio and music technologies, engineering, and philosophy. Starting from Aristotle’s idea of the soul, the investigation of animation follows the parallel development of philosophical con- cepts (i.e. soul, mind, spirit, agency) and technical concepts (i.e. mechanics, automation, cybernetics) over many centuries. -

Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, Conductor

Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, conductor November 13, 2020 Friday Presented Virtually 7:30 pm Program Mood Swings Interludes composed by members of Dr. Cynthia Folio’s Post-Tonal Theory Class. Performed by Allyson Starr, flute and Joshua Schairer, bassoon. Aria della battaglia (1590) Andrea Gabrieli (1532–1585) ed. Mark Davis Scatterday Love Letter in Miniature Marcos Acevedo-Arús Fratres (1977) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) arr. Beat Briner Schyler Adkins, graduate student conductor Echoes Allyson Starr Motown Metal (1994) Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Unmoved Joshua Schairer Petite Symphonie (1885) Charles Gounod (1818–1893) I. Adagio, Allegro II. Andante cantabile III. Scherzo: Allegro moderato IV. Finale: Allegretto Ninety-fourth performance of the 2020-2021 season. Bulls-Eye (2019) Viet Cuong (b. 1990) Musings Spicer W. Carr Drei Lustige Märsche, Op. 44 (1926) Ernst Krenek (1900–1991) Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, conductor FLUTE TRUMPET Ruby Ecker-Wylie Maria Carvell Hyerin Kim Anthony Casella Jill Krikorian Daniel Hein Allyson Starr Jacob Springer Malinda Voell Justin Vargas OBOE TROMBONE Geoffrey Deemer Rachel Core Lexi Kroll Jeffrey Dever Brandon Lauffer Samuel Johnson Amanda Rearden Omeed Nyman Sarah Walsh Andrew Sedlacsick CLARINET EUPHONIUM Abbegail Atwater Jason Costello Wendy Bickford Veronica Laguna Samuel Brooks Cameron Harper TUBA Alyssa Kenney Mary Connor Will Klotsas Chris Liounis Alexander Phipps PERCUSSION BASSOON Emilyrose Ristine Rick Barrantes Joel Cammarota Noah Hall Jake Strovel Tracy Nguyen Milo Paperman Collin Odom Andrew Stern Joshua Schairer PIANO SAXOPHONE Madalina Danila Jocelyn Abrahamzon Ian McDaniel GRADUATE ASSISTANTS Sam Scarlett Schyler Adkins Kevin Vu Amanda Dumm HORN Isaac Duquette Kasey Friend MacAdams Danielle O’Hare Jordan Spivack Lucy Smith Program Notes Aria della battaglia Andrea Gabrieli A prominent figure in Renaissance Italy, Andrea Gabrieli acted as principal organist and composer at the St. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Dena Derose, Vocals and Piano Martin Wind, Bass • Matt Wilson, Drums with Sheila Jordan, Vocal • Jeremy Pelt, Trumpet Houston Person, Tenor Saxophone

19 juin, 2020. June 19, 2020. MAN MAN DREAM HUNTING IN THE VALLEY OF THE IN-BETWEEN CD / 2XLP / CS / DIGITAL SP 1350 RELEASE DATE: MAY IST, 2020 TRACKLISTING: 1. Dreamers 2. Cloud Nein 3. On the Mend 4. Lonely Beuys 5. Future Peg 6. Goat 7. Inner Iggy 8. Hunters 9. Oyster Point 10. The Prettiest Song in the World 11. Animal Attraction 12. Sheela 13. Unsweet Meat 14. Swan 15. Powder My Wig 16. If Only 17. In the Valley of the In-Between GENRE: Alternative Rock Honus Honus (aka Ryan Kattner) has devoted his career to exploring the uncertainty between life’s extremes, beauty, and ugliness, order and chaos. The songs on Dream Hunting in the Valley of the In-Between, Man Man’s first album in over six years and their Sub Pop debut, are as intimate, soulful, and timeless as they are audaciously inventive and daring, resulting in his best Man Man album to date. 0 9 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 2 209 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 1 5 CD Packaging: Digipack 2xLP Packaging: Gatefold jacket w/ custom The 17-track effort, featuring “Cloud Nein,” “Future Peg,” “On the with poster insert dust sleeves and etching on side D Includes mp3 coupon Mend” “Sheela,” and “Animal Attraction,” was produced by Cyrus NON-RETURNABLE Ghahremani, mixed by S. Husky Höskulds (Norah Jones, Tom Waits, Mike Patton, Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Allen Toussaint), and mastered by Dave Cooley (Blood Orange, M83, DIIV, Paramore, Snail Mail, clipping). Dream Hunting...also includes guest vocals from Steady Holiday’s Dre Babinski on “Future Peg” and “If Only,” and Rebecca Black (singer of the viral pop hit, “Friday”) on “On The Mend” and “Lonely Beuys.” The album follows the release of “Beached” and “Witch,“ Man Man’s contributions to Vol. -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

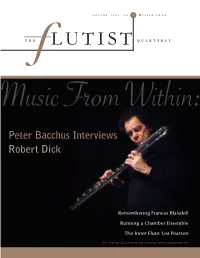

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

Computer Music

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF COMPUTER MUSIC Edited by ROGER T. DEAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published as an Oxford University Press paperback ion Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Oxford handbook of computer music / edited by Roger T. Dean. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-979103-0 (alk. paper) i. Computer music—History and criticism. I. Dean, R. T. MI T 1.80.09 1009 i 1008046594 789.99 OXF tin Printed in the United Stares of America on acid-free paper CHAPTER 12 SENSOR-BASED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND INTERACTIVE MUSIC ATAU TANAKA MUSICIANS, composers, and instrument builders have been fascinated by the expres- sive potential of electrical and electronic technologies since the advent of electricity itself. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: a Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-1-2012 Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Davis, Christopher Leigh, "Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke" (2012). Dissertations. 634. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/634 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts December 2012 ABSTRACT EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis December 2012 British flutist Ian Clarke is a leading performer and composer in the flute world. His works have been performed internationally and have been used in competitions given by the National Flute Association and the British Flute Society. Clarke’s compositions are also referenced in the Peters Edition of the Edexcel GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) Anthology of Music as examples of extended techniques. The significance of Clarke’s works lies in his unique compositional style. His music features sounds and styles that one would not expect to hear from a flute and have elements that appeal to performers and broader audiences alike. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

The Development of the Flute As a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era

Musical Offerings Volume 2 Number 1 Spring 2011 Article 2 5-1-2011 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Anna J. Reisenweaver Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Musicology Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Reisenweaver, Anna J. (2011) "The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era," Musical Offerings: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2011.2.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol2/iss1/2 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Document Type Article Abstract As one of the oldest instruments known to mankind, the flute is present in some form in nearly every culture and ethnic group in the world. However, in Western music in particular, the flute has taken its place as an important part of musical culture, both as a solo and an ensemble instrument. The flute has also undergone its most significant technological developments in Western musical culture, moving from the bone keyless flutes of the Prehistoric era to the gold and silver instruments known to performers today.