Separation of Powers in Comparative Perspective: How Much Protection for the Rule of Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary, Presidential and Semi-Presidential Democracies Democracies Are Often Classified According to the Form of Government That They Have

Parliamentary, Presidential and Semi-Presidential Democracies Democracies are often classified according to the form of government that they have: • Parliamentary • Presidential • Semi-Presidential Legislative responsibility refers to a situation in which a legislative majority has the constitutional power to remove a government from office without cause. A vote of confidence is initiated by the government { the government must resign if it fails to obtain a legislative majority. A vote of no confidence is initiated by the legislature { the government must resign if it fails to obtain a legislative majority. A constructive vote of no confidence must indicate who will replace the government if the incumbent loses a vote of no confidence. A vote of no confidence is initiated by the legislature { the government must resign if it fails to obtain a legislative majority. A constructive vote of no confidence must indicate who will replace the government if the incumbent loses a vote of no confidence. A vote of confidence is initiated by the government { the government must resign if it fails to obtain a legislative majority. The defining feature of presidential democracies is that they do not have legislative responsibility. • US Government Shutdown, click here In contrast, parliamentary and semi-presidential democracies both have legislative responsibility. • PM Question Time (UK), click here In addition to legislative responsibility, semi-presidential democracies also have a head of state who is popularly elected for a fixed term. A head of state is popularly elected if she is elected through a process where voters either (i) cast a ballot directly for a candidate or (ii) they cast ballots to elect an electoral college, whose sole purpose is to elect the head of state. -

Dahl and Charles E

PLEASE READ BEFORE PRINTING! PRINTING AND VIEWING ELECTRONIC RESERVES Printing tips: ▪ To reduce printing errors, check the “Print as Image” box, under the “Advanced” printing options. ▪ To print, select the “printer” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. DO NOT print using “File>Print…” in the browser menu. ▪ If an article has multiple parts, print out only one part at a time. ▪ If you experience difficulty printing, come to the Reserve desk at the Main or Science Library. Please provide the location, the course and document being accessed, the time, and a description of the problem or error message. ▪ For patrons off campus, please email or call with the information above: Main Library: [email protected] or 706-542-3256 Science Library: [email protected] or 706-542-4535 Viewing tips: ▪ The image may take a moment to load. Please scroll down or use the page down arrow keys to begin viewing this document. ▪ Use the “zoom” function to increase the size and legibility of the document on the screen. The “zoom” function is accessed by selecting the “magnifying glass” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproduction of copyrighted material. Section 107, the “Fair Use” clause of this law, states that under certain conditions one may reproduce copyrighted material for criticism, comment, teaching and classroom use, scholarship, or research without violating the copyright of this material. Such use must be non-commercial in nature and must not impact the market for or value of the copyrighted work. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

A 10-Year Perspective of the Merger of Louisville and Jefferson County, KY: Louisville Metro Vaults from 65Th Th to 18 Largest City in the Nation

A 10-Year Perspective of the Merger of Louisville and Jefferson County, KY: Louisville Metro Vaults From 65th th to 18 Largest City in the Nation Jeff Wachter September, 2013 Over the past 50 years, the idea of merging a city with its neighboring or surrounding county has been contemplated in many American cities, voted upon in a few, and enacted in even fewer. The most prominent American mergers have been Jacksonville, FL; Indianapolis, IN; Nashville, TN; and Lexington, KY. Other cities—including Pittsburgh, PA and Memphis, TN— have attempted mergers, but failed at various stages in the process. City/county consolidation has been a controversial topic, with advocates and opponents pointing to different metrics that support their expectations for the consequences of a merger. Louisville, KY, which merged with Jefferson County on January 1st, 2003, is the most recent example of a city/county consolidation executed by a major American city. This report examines how Louisville Metro has performed over the past decade since the merger took effect by analyzing the city’s economy, population, government spending and efficiency, and public opinion about the merger. In the late 1990s, business and political leaders came together in an attempt to address some of the issues facing the Louisville region, including a long declining population and tax- base, escalating government spending, and multiple economic development organizations fighting to recruit the same businesses (often to the detriment of the greater Louisville region at- large). These leaders determined that a merger of the Louisville and Jefferson County governments was in the best interests of the region, despite the contentious nature of merger debates. -

The Cultural Politics of Proxy-Voting in Nagaland

TIF - The Cultural Politics of Proxy-Voting in Nagaland JELLE J P WOUTERS June 7, 2019 RODERICK WIJUNAMAI Voters in Kohima, Nagaland | PIB Photo Nagaland’s voter turnouts are often the highest in the country, and it may be so this time around as well. But why was the citizenry of Nagaland so keen to vote for their lone, largely ineffectual representative in the Lok Sabha? Of all truisms about democracy, one that is held to be particularly true is that any democracy’s vitality and verve depends on its voter turnouts during elections. As the acclaimed political and social theorist Steven Lukes (1975: 304) concluded long ago: “Participation in elections can plausibly be interpreted as the symbolic affirmation of the voters’ acceptance of the political system and of their role within it.” Indian democracy thence draws special attention; not just for its trope of being the world’s largest democracy (Indian voters make up roughly one-sixth of the world’s electorate) but for the democratic and electoral effervescence reported all across the country. While a disenchantment with democratic institutions and politics is now clearly discernible in large swathes of the so-called “West” and finds its reflection in declining voter turnouts, to the point almost where a minority of citizens elect majority governments, India experiences no such democratic fatigue. Here voter turnouts are not just consistently high, but continue to increase and now habitually outdo those of much older democracies elsewhere. And if India’s official voter turnouts are already high, they might well be a low estimate still. -

Types of Democracy the Democratic Form of Government Is An

Types of Democracy The democratic form of government is an institutional configuration that allows for popular participation through the electoral process. According to political scientist Robert Dahl, the democratic ideal is based on two principles: political participation and political contestation. Political participation requires that all the people who are eligible to vote can vote. Elections must be free, fair, and competitive. Once the votes have been cast and the winner announced, power must be peacefully transferred from one individual to another. These criteria are to be replicated on a local, state, and national level. A more robust conceptualization of democracy emphasizes what Dahl refers to as political contestation. Contestation refers to the ability of people to express their discontent through freedom of the speech and press. People should have the ability to meet and discuss their views on political issues without fear of persecution from the state. Democratic regimes that guarantee both electoral freedoms and civil rights are referred to as liberal democracies. In the subfield of Comparative Politics, there is a rich body of literature dealing specifically with the intricacies of the democratic form of government. These scholarly works draw distinctions between democratic regimes based on representative government, the institutional balance of power, and the electoral procedure. There are many shades of democracy, each of which has its own benefits and disadvantages. Types of Democracy The broadest differentiation that scholars make between democracies is based on the nature of representative government. There are two categories: direct democracy and representative democracy. We can identify examples of both in the world today. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Judicial Independence, Judicial Accountability, and Judicial Reform

The Importance of Judicial Independence and Accountability Roger K. Warren, President, The National Center for State Courts Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. My topic for these remarks is “Judicial Independence, Judicial Accountability, and Judicial Reform.” Let me begin by expressing my admiration, President Weng, for your efforts and those of the Judicial Yuan of the Republic of China to reform the Taiwan Judiciary and build greater public trust and confidence in the work of the judiciary. I, too, am no stranger to judicial reform. I worked as a legal aid attorney representing people who could not afford to hire an attorney before I became a judge, and was active in judicial reform activities while serving as a judge in the State of California for twenty years before I left that position to become president of the National Center for State Courts, which is the preeminent American judicial reform organization and seeks to promote judicial reform in the United States and around the world. The cry for justice is universal. Responding to that cry all over the world, lawyers, judges, court administrators, and judicial educators seek to reform justice systems and promote the rule of law. At this time in our world’s history, there is no higher calling. This morning I would like to reflect with you on our respective judicial reform efforts—in the U.S., Taiwan, and around the world—and discuss those efforts against the backdrop of the principles of judicial independence and judicial accountability. Let me start with the rule of law. The rule of law is an essential feature of all democratic countries. -

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Latent Heat: Changing Forms of Activism Under Repressi

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Latent Heat: Changing Forms of Activism under Repressive Authoritarian Regimes: A Case Study of Egypt, 2000-2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts/Science By Shireen Mohamed Zayed under the supervision of Dr. James H. Sunday August/2017 1 Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 3 Dedication ................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgment .......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review ............................................................. 6 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Literature Review: Beyond Repression and Coercion Alone ....................................... 8 1.2.1 Operational Definitions .................................................................................. 9 1.2.2 Relationship between Repression and Activism ............................................... 10 1.2.3 Scholarly Debate: Activism Under Authoritarian Regimes ................................. 12 1.3 Theoretical Framework ...................................................................................... -

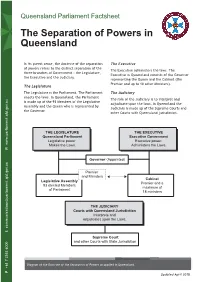

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Justice Reform in Mexico: Change and Challenges in the Judicial Sector

Justice Reform in Mexico: Change and Challenges in the Judicial Sector David A. Shirk Working Paper Series on U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation April 2010 1 Brief Project Description This Working Paper is the product of a joint project on U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation coordinated by the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego. As part of the project, a number of research papers have been commissioned that provide background on organized crime in Mexico, the United States, and Central America, and analyze specific challenges for cooperation between the United States and Mexico, including efforts to address the consumption of narcotics, money laundering, arms trafficking, intelligence sharing, police strengthening, judicial reform, and the protection of journalists. This paper is being released in a preliminary form to inform the public about key issues in the public and policy debate about the best way to confront drug trafficking and organized crime. Together the commissioned papers will form the basis of an edited volume to be released later in 2010. All papers, along with other background information and analysis, can be accessed online at the web pages of either the Mexico Institute or the Trans-Border Institute and are copyrighted to the author. The project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. The views of the author do not represent an official position of the Woodrow Wilson Center or of the University of San Diego. For questions related to the project, for media inquiries, or if you would like to contact the author please contact the project coordinator, Eric L. -

Antitrust and Regulatory Federalism: Races Up, Down, and Sideways

ESSAY ANTITRUST AND REGULATORY FEDERALISM: RACES UP, DOWN, AND SIDEWAYS ELEANOR M. Fox* In this Essay, Professor Eleanor Fox analyzes regulatory competition and regula- tory federalism with respect to competition law. In considering whether some de- gree of higher-than-national-levelregulation is wis Fox observes possible races to the bottom and the top, as vell as the race to be te model for the world. Sie then analyzes regulatorydisregard. the tendency of nationalsystems and their actors to disregardtheir neighbors and to disregard the problem of excessively overlapping regulatorysystems. Professor Fox concludes that there is a modest and marginal race to the bottom; that there is also a race to the top; that there is little competition as such among competition regimes to attractinvestment, but there is competition between the UnitedStates and the European Union to export competition law mod- els to the rest of the worId and dm4 in view of nationalisticraces and regulatory disregard,there is a case for the internationalizationof certain speciftc procedures and principles. INTODUCrION Antitrust law is national. Markets-many of them-are global. Arguments have been made for internationalizing antitrust law or raising surveillance of anticompetitive restraints to a level higher than that of the nation.1 Analysis of these arguments is complicated by the fact that there are many versions of antitrust law and its goals, both descriptive and normative, and there are many possibilities for inter- nationalization or cooperation on antitrust rules and their enforcement. * Walter J. Derenberg Professor of Trade Regulation, New York University School of Law. B.A., 1956, Vassar College; LL.B., 1961, New York University.