How Stevenson Altered the Second Narrator of Treasure Island Patricia Whaley Hardesty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson adapted for the stage by Stewart Skelton Stewart E. Skelton 6720 Franklin Place, #404 Copyright 1996 Hollywood, CA 90028 213.461.8189 [email protected] SETTING: AN ATTIC A PARLOR AN INN A WATERFRONT THE DECK OF A SHIP AN ISLAND A STOCKADE ON THE ISLAND CAST: VOICE OF BILLY BONES VOICE OF BLACK DOG VOICE OF MRS. HAWKINS VOICE OF CAP'N FLINT VOICE OF JIM HAWKINS VOICE OF PEW JIM HAWKINS PIRATES JOHNNY ARCHIE PEW BLACK DOG DR. LIVESEY SQUIRE TRELAWNEY LONG JOHN SILVER MORGAN SAILORS MATE CAPTAIN SMOLLETT DICK ISRAEL HANDS LOOKOUT BEN GUNN TIME: LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TREASURE ISLAND/Skelton 1 SCENE ONE (A treasure chest sits alone on plank flooring. We hear the creak of rigging on a ship set adrift. As the lights begin to dim, we hear menacing, thrilling music building in the background. When a single spot is left illuminating the chest, the music comes to a crashing climax and quickly subsides to continue playing in the background. With the musical climax, the lid of the chest opens with a horrifying groan. Light starts to emanate from the chest, and the spotlight dims. Voices and the sounds of action begin to issue forth from the chest. The music continues underneath.) VOICE OF BILLY BONES (singing) "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!" VOICE OF BLACK DOG Bill! Come, Bill, you know me; you know an old shipmate, Bill, surely. -

Scribner Classics) Treasure Island (Scribner Classics)

[Ebook free] Treasure Island (Scribner Classics) Treasure Island (Scribner Classics) IoR2HHmRM Treasure Island (Scribner Classics) 7yXAvxBUr VJ-45300 8uC2GS2vv USmix/Data/US-2012 W0x7cSBnh 4.5/5 From 663 Reviews xQsCp2mlC Robert Louis Stevenson k35GQ1Zn3 ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF WU4bCiSgA xisCGNZgH 8onerLhGW mwqPwthYT ZVmw4iWRE 3OyvmqElp lptxPU3FG pbvO2PFVA 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. I ordered a hardcover Ru6CZzLAx Treasure Island. The image shows ...By Phillip J. JacksonI ordered a hardcover HXuQLYPlt Treasure Island. The image shows a leather bound book similar to the pZIxh1rLL hardcovers for Treasure Island I've seen before. I didn't receive the book GY4KjI1Tk pictured. I got a children's abridged illustrated large format Treasure Island. PTy6WuhGm The image supplied here was supplied intentionally to mislead the buyer into to eeEhWce2b thinking they were getting the leather bound hardcover with small illustrations OCOFEPQrp at the chapter headings but instead sold a thin large format, hard to read text IBG584wAq on illustration book. I'm not mad at it. I just want the leather bound hard cover iiDqPr5sD that I was looking for and if you are looking for it too, this isn't it.0 of 0 people 32toKHZwl found the following review helpful. This is a classic. The writing style shows the Xx3tQBGqw ...By Tracy MitchellThis is a classic. The writing style shows the classic 3CQ3fsEHi structure with the English spelling. Readers who are looking for an ldquo;easy E4oZJKQvs readrdquo; will want an abridged version...this is not for you. If you want the wHiPqeNsy full experience of the rich language writing style of Robert Louis Stevenson, then keep reading.The story describes a young boyrsquo;s adventure on the high seas in search of treasure. -

Treasure Island

School Radio Treasure Island 6. The stockade and the pirates attack Narrator: On Treasure Island you might be forgiven for thinking a war was taking place. Anchored in the bay, the Hispaniola is firing her cannon deep into the woods. And through the trees, the pirates advance, muskets blazing. Oblivious to the danger, young Jim Hawkins races through the undergrowth heading for the Union Jack that flies bravely atop the trees. When he gets there, it’s a relief to find there’s shelter. A tall wooden stockade stands in a clearing - and inside it, his old friends Squire Trelawney, Doctor Livesey, Captain Smollett and a handful of faithful sailors, are fending off a full-blown attack from the pirates. Jim: Doctor! Squire! Captain! Let down the drawbridge! It’s me! Dr Livesey: Quickly, men, let the boy in! Squire: Jim - we thought we’d lost you! Hunter: Happen as still might unless we keep them muskets firing. Squire: Ah, yes, good thinking my man. Repel the blackguards! A sovereign for every man we put down! Narrator: But the pirates give up the fight - for now. Jim and the others exchange news. It turns out that the stockade they’re in was built many years ago by Captain Flint as a stronghold if ever he should be attacked. Squire Trelawney and the others just beat Silver and the pirates to it - though they lost a couple of good men in so doing. They managed to salvage enough guns, ammunition and food from the ship to keep them going for a couple of weeks but not much more. -

Treasure Island”

A Teacher’s Guide to Missoula Children’s Theatre’s “Treasure Island” Dear Educator, As you make plans for your students to attend an upcoming presentation of the Arts for Youth program at the Lancaster Performing Arts Center, we invite you to prepare your students by using this guide to assure that from beginning to end; the experience is both memorable and educationally enriching. The material in this guide is for you the teacher, and will assist you in preparing your students before the day of the event, and extending the educational value to beyond the walls of the theatre. We provide activity and/or discussion ideas, and other resources that will help to prepare your students to better understand and enjoy what they are about to see, and to help them connect what they see on stage to their studies. We also encourage you to discuss important aspects of the artistic experience, including audience etiquette. We hope that your students find their imagination comes alive as lights shine, curtains open, and applause rings through Lancaster Performing Arts Center. As importantly, we hope that this Curriculum Guide helps you to bring the arts alive in your classroom! Thank you for helping us to make a difference in the lives of our Antelope Valley youth. Arts for Youth Program Lancaster Performing Arts Center, City of Lancaster Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of the California -

Treasure Island

UNIT: TREASURE ISLAND ANCHOR TEXT UNIT FOCUS Students read a combination of literary and informational texts to answer the questions: What are different types of treasure? Who hunts for treasure and how? Why do people Great Illustrated Classics Treasure Island, Robert Louis search for treasure? Students also discuss their personal treasures. Students work to Stevenson understand what people are willing to do to get treasure and how different types of treasure have been found, lost, cursed, and stolen over time. RELATED TEXTS Text Use: Describe characters’ changing motivations in a story, read and apply nonfiction Literary Texts (Fiction) research to fictional stories, identify connections of ideas or events in a text • The Ballad of the Pirate Queens, Jane Yolen Reading: RL.3.1, RL.3.2, RL.3.3, RL.3.4, RL.3.5, RL.3.6, RL.3.7, RL.3.10, RI.3.1, RI.3.2, RI.3.3, • “The Curse of King Tut,” Spencer Kayden RI.3.4, RI.3.5, RI.3.6, RI.3.7, RI.3.8, RI.3.9, RI.3.10 • The Stolen Smile, J. Patrick Lewis Reading Foundational Skills: RF.3.3d, RF.3.4a-c • The Mona Lisa Caper, Rick Jacobson Writing: W.3.1a-d, W.3.2a-d, W.3.3a-d, W.3.4, W.3.5, W.3.7, W.3.8, W.3.10 Speaking and Listening: SL.3.1a-d, SL.3.2, SL.3.3, SL.3.4, SL.3.5, SL.3.6 Informational Texts (Nonfiction) • “Pirate Treasure!” from Magic Tree House Fact Language: L.3.1a-i; L.3.2a, c-g; L.3.3a-b; L.3.4a-b, d; L.3.5a-c; L.3.6 Tracker: Pirates, Will Osborne and Mary Pope CONTENTS Osborne • Finding the Titanic, Robert Ballard Page 155: Text Set and Unit Focus • “Missing Mona” from Scholastic • -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

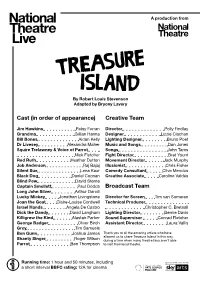

Cast (In Order of Appearance) Creative Team

A production from By Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery Cast (in order of appearance) Creative Team Jim Hawkins Patsy Ferran Director Polly Findlay Grandma Gillian Hanna Designer Lizzie Clachan Bill Bones Aidan Kelly Lighting Designer Bruno Poet Dr Livesey Alexandra Maher Music and Songs Dan Jones Squire Trelawney & Voice of Parrot Songs John Tams Nick Fletcher Fight Director Bret Yount Red Ruth Heather Dutton Movement Director Jack Murphy Job Anderson Raj Bajaj Illusionist Chris Fisher Silent Sue Lena Kaur Comedy Consultant Clive Mendus Black Dog Daniel Coonan Creative Associate Caroline Valdés Blind Pew David Sterne Captain Smollett Paul Dodds Broadcast Team Long John Silver Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey Jonathan Livingstone Director for Screen Tim van Someren Joan the Goat Claire-Louise Cordwell Technical Producer Israel Hands Angela De Castro Christopher C. Bretnall Dick the Dandy David Langham Lighting Director Bernie Davis Killigrew the Kind Alastair Parker Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher George Badger Oliver Birch Assistant Director Laura Vallis Grey Tim Samuels Ben Gunn Joshua James Thank you to all the amazing artists who have allowed us to share Treasure Island in this way, Shanty Singer Roger Wilson during a time when many theatre fans aren’t able Parrot Ben Thompson to visit their local theatre. Running time: 1 hour and 50 minutes, including a short interval BBFC rating: 12A for cinema Help Jim Hawkins find the buried gold! Can you trace your way from the ship to X marks the spot and the treasure? Image: Freepik.com Image: Did you know? Excerpts from Treasure Island show programme articles by Andrew Lambert, David Cordingly and Tristan Gooley. -

Jim Hawkins Captain Smollett

Jim Hawkins Jim Hawkins is a fictional character in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island. He is the protagonist and the narrator of the story. Jim is 13 years old so the children may identify with him. He works in his family’s inn. In the story, he is the one who finds the treasure map. He doesn’t keep it for himself, he shares it with all his friend, Dr Livesey. He is sometimes clumsy and reckless by his actions. He is quite naive. He is the main character of the novel, He has all the Hero’s qualities. This hero represents the childhood’s innocence, courage and hope. Captain Smollett Alexander Smollet is the English captain of the schooner the Espanola in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel. He is the opposite of Long John Silver, he gave his life to his homeland. He is a right and honest man, and he remains faithful to his values. He has a lot of experience and he is very brave. During the mutiny, he takes the control of the operations and rations his companions to finally lead them to the battle. In the story, Doctor Livesey expresses his admiration to Alexander Smollett. Billy Bones Billy bones is a key character of the story, when he arrives to the inn. He introduces himself as an cruel man. He owns the famous treasure map which belonged to Captain Flint. This is why a lot of buccaneers are looking for him like Long John Silver. Billy is an alcoholic and it makes him aggressive. -

TREASURE ISLAND Reimagined! Based on the Book by Robert Louis Stevenson SYNOPSIS

TREASURE ISLAND Reimagined! Based on the book by Robert Louis Stevenson SYNOPSIS Act I (50 minutes) Ahoy, Mateys! Join Jim Hawkins, Ben Gunn, Long John Silver, and the whole crew as they tell the classic story Treasure Island in an original and exciting version debuting at Dallas Children’s Theater! The play begins with Jim and Ben simultaneously telling their stories. Although their stories begin ten years apart, they were both deceived as young boys by the same scurvy pirate, Long John Silver. Year: 1871 Ben Gunn needs work after being abandoned by his father. He hears about a potential job working on Captain Flint’s pirate ship. Ben is dismayed when turned down by Flint, but soon meets Long John Silver who brings Ben on board Flint’s boat as the cabin boy. Year: 1881 Jim Hawkins and his friends are playing pirates when they are approached by an actual pirate, Billy Bones! Billy, protecting a chest he’s brought with him, tells the kids about Captain Flint’s lost treasure, the fifteen pirates who died burying it, and the pirate they need to beware of: the man with one-leg. When Jim’s mother approaches them, Billy asks for a room in the Hawkins’ inn. As she prepares his room, Billy warns Jim to look out for the one-legged man. That night, Jim has nightmares about a giant one-legged man. Year: 1871 Ben Gunn and Long John Silver sit together on the ship, looking at the stars. Long John tells Ben about the importance of constellations and the story of how proud Orion defeated every dangerous creature the gods sent his way until the gods sent a scorpion that killed Orion. -

Jim Hawkins Meets Long John Silver

Treasure Island 3a) Listening One: Jim Hawkins Meets Long John Silver Read and listen to a conversation between Jim and Long John Silver. LJS Hello there, Jim boy. Jim Hello. Who are you? LJS My name is Long John Silver. And you are…? Jim Oh yes, my name is Jim. Jim Hawkins, sir. LJS Hawkins! A fine name! And are you looking for a ship, Master Jim Hawkins? Jim Yes, I am! I’m looking for a big ship to sail to a secret Treasure Island…oops! LJS A secret Treasure Island? Jim: Yes, err…I mean no! I mean, sssshhhh, (whispers) it’s a secret. LJS A secret. I understand. Well, don’t worry, your secret’s safe with me. I have the perfect ship for you. Jim Really? LJS Yes, her name is The Hispaniola. If you want a ship to go looking for treasure then she’s the perfect ship for you. Jim Great! LJS So how much money have you got, Jim boy? Jim I don’t have any money, sir? LJS No money, eh? Well, look, Jim boy. I’m a very generous person. If you work on my ship, cleaning the deck, climbing the mast, etc. I will take you to Treasure Island free of charge. Jim: You’ll take me to Treasure Island? For free? LJS: Yes, for free! Jim: OK. It’s a deal. LJS: Good. Now come on, Jim boy. Let’s get ready, on The Hispaniola! IPA IP A This activity is designed to be used in conjunction with a performance of IPA Production’s Treasure Island. -

TREASURE ISLAND SQUIRE TRELAWNEY, Dr. Livesey, and the Rest of These Gentlemen Having Asked Me to Write Down the Whole Particula

A Ria Press Edition of Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Page 1 of 53. TREASURE ISLAND call me? You mought call me captain. Oh, I see what you’re at— there”; and he threw down three or four gold pieces on the by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1883 threshold. “You can tell me when I’ve worked through that,” Ria Press says he, looking as fierce as a commander. To S.L.O., an American gentleman in accordance with whose And indeed bad as his clothes were and coarsely as he spoke, classic taste the following narrative has been designed, it is now, he had none of the appearance of a man who sailed before the in return for numerous delightful hours, and with the kindest mast, but seemed like a mate or skipper accustomed to be obeyed wishes, dedicated by his affectionate friend, the author. or to strike. The man who came with the barrow told us the mail TO THE HESITATING PURCHASER had set him down the morning before at the Royal George, that If sailor tales to sailor tunes, he had inquired what inns there were along the coast, and hearing Storm and adventure, heat and cold, ours well spoken of, I suppose, and described as lonely, had cho- If schooners, islands, and maroons, sen it from the others for his place of residence. And that was all And buccaneers, and buried gold, we could learn of our guest. And all the old romance, retold He was a very silent man by custom. All day he hung round Exactly in the ancient way, Can please, as me they pleased of old, the cove or upon the cliffs with a brass telescope; all evening he The wiser youngsters of today: sat in a corner of the parlour next the fire and drank rum and wa- —So be it, and fall on! If not, ter very strong.