Gideon Planish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900 Nicole Zeftel The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2613 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SICKLY SENTIMENTALISM: SYMPATHY AND PATHOLOGY IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE, 1866-1900 by NICOLE ZEFTEL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 NICOLE ZEFTEL All Rights Reserved ! ii! Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date ! Hildegard Hoeller Chair of Examining Committee Date ! Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Eric Lott Bettina Lerner THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ! iii! ABSTRACT Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel Advisors: Hildegard Hoeller and Eric Lott Sickly Sentimentalism: Pathology and Sympathy in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 examines the work of four American women novelists writing between 1866 and 1900 as responses to a dominant medical discourse that pathologized women’s emotions. -

Victoria Woodhull: a Radical for Free Love Bernice Redfern

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1980s San José Studies Fall 10-1-1984 San José Studies, Fall 1984 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_80s Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, Fall 1984" (1984). San José Studies, 1980s. 15. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_80s/15 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1980s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sa1an~s asof Nvs SAN JOSE Volume X, Number 3 ARTICLES The Declaration and the Constitution Harry V. Jaffa . 6 A Moral and a Religious People Robert N. Bellah .............................................. 12 The Constitution and Civic Education William J. Bennett ............................................ 18 Conversation: The Higher Law Edward J. Erler and T. M. Norton .............................. 22 Everyone Loves Money in The Merchant of Venice Norman Nathan .............................................. 31 Victoria Woodhull: A Radical for Free Love Bernice Redfern .............................................. 40 Goneril and Regan: 11So Horrid as in Woman" Claudette Hoover ............................................ 49 STUDIES Fall1984 FICTION The Homed Beast Robert Burdette Sweet ........................................ 66 Wars Dim and -

Reading Guide Other Powers

Reading Guide Other Powers By Barbara Goldsmith ISBN: 9780060953324 Plot Summary Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull is a portrait of the tumultuous last half of the nineteenth century, when the United States experienced the Civil War, Reconstruction, Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, and the 1869 collapse of the gold market. A stunning combination of history and biography, Other Powers interweaves the stories of the important social, political, and religious players of America's Victorian era with the scandalous life of Victoria Woodhull--Spiritualist, woman's rights crusader, free-love advocate, stockbroker, prostitute, and presidential candidate. This is history at its most vivid, set amid the battle for woman suffrage, the Spiritualist movement that swept across the nation in the age of Radical Reconstruction following the Civil War, and the bitter fight that pitted black men against white women in the struggle for the right to vote. The book's cast: Victoria Woodhull, billed as a clairvoyant and magnetic healer--a devotee and priestess of those "other powers" that were gaining acceptance across America--in her father's traveling medicine show . spiritual and financial advisor to Commodore Vanderbilt . the first woman to address a joint session of Congress, where--backed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony--she presents an argument that women, as citizens, should have the right to vote . becoming the "high priestess" of free love in America (fiercely believing the then-heretical idea that women should have complete sexual equality with men) . making a run for the presidency of the United States against Horace Greeley and Ulysses S. -

Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895 Elizabeth B

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Publications Betsy Clark Living Archive 10-1989 The olitP ics of God and the Woman's Vote: Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895 Elizabeth B. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/clark_pubs Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth B. Clark, The Politics of God and the Woman's Vote: Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895, (1989). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/clark_pubs/3 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Betsy Clark Living Archive at Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICS OF GOD AND THE WOMAN'S VOTE: RELIGION IN THE AMERICAN SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT, 1848-1895 Elizabeth Battelle Clark A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY October, 1989 © Copyright by Elizabeth Battelle Clark 1989 All Rights Reserved Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the role of religion— both liberal and evangelical Protestantism— in the development of a feminist political theory in America during the nineteenth century and how that feminist theory in turn helped to transform American liberalism. Chapter 1 looks for the genesis of women's rights language, not in the republican rhetoric of the Founding Fathers, but in the teachings of liberal Protestantism and its links with laissez-faire economic theory. -

Mediately Draws You in with Believable Dialogue and a Subject Matter That Makes You Want to Know More

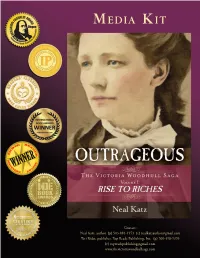

M EDIA KIT Contact: Neal Katz, author (p) 503-883-1973 (e) [email protected] Teri Rider, publisher, Top Reads Publishing, Inc. (p) 760-458-9393 (e) [email protected] www.thevictoriawoodhullsaga.com Complete listing of Awards Won – Outrageous, The Victoria Woodhull Saga, Volume 1: Rise to Riches (to date, April 16, 2017) Outrageous has won 9 major National Awards for Independent Publishing, and 1 International Award in a field of all published books. Individual awards listed below. IBPA Benjamin Franklin – Bill Fisher Award for Best First Book by a Publisher, Gold Medal http://iBpaBenjaminfranklinawards.com/2016-ibpa-bfa-finalists/#Bill1 Video interview: https://youtu.Be/2HQJ8tF1niI?list=PL0j72Ir-3hZEAu91MJ9lVwLYFuaPFPUZ4 Independent Publisher Book Awards, IPPY – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction http://www.independentpublisher.com/article.php?page=2045 Reader’s Favorite – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction / Personage https://readersfavorite.com/book-review/outrageous International Book Awards – Winner, Best New Fiction http://www.internationalbookawards.com/2016awardannouncement.html Indie Reader Discovery Award – Second Place Winner in Fiction http://indiereader.com/indiereader-discovery-awards/past-winners/ Next Generation Indie Book Award – Finalist Historical Fiction http://www.indieBookawards.com/winners/2016 Independent Author Network (IAN) Book of the Year Awards – Finalist in Two Categories: Historical Fiction, First Novel http://www.independentauthornetwork.com/2016-book-of-the-year-winners.html Chanticleer -

Early Women of Wall Street: “Sports of Nature” Shirley M. Mueller Published on Health Care Professionals Live August 3, 2009

Early Women of Wall Street: “Sports of Nature” Shirley M. Mueller Published on Health Care Professionals Live August 3, 2009 “Woman's ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and brutality of men than her ability to vote," said Victoria Woodhull in the late 19th century. This independence on the part of the Woodhull marked her as a „sport of nature,‟ by Eunice Barnard in an article she wrote in the April, 1929 North American Review. Hetty Green, also a nineteenth century financial pioneer, was similarly designated. Currently these „sports of nature‟ are receiving attention in “Women of Wall Street,” an exhibit at the Museum of American Finance in New York City running until January 16, 2010. Since learning from the past can inform the future, reviewing the exhibit is not only informative and interesting, but could be helpful to investors who seek to emulate successful predecessors. The two „sports of nature,‟ which Barnard referred to, were different than other women of their time. Their qualities of independence, self determination and ability to focus were not necessarily welcomed by all of their contemporaries. Still, these were the traits that no doubt lead to their investing genius. Victoria Woodhull, along with her sister, Tennessee Claflin, opened the first female brokerage house on Wall Street in 1870. Though the girls were from a poor home in Ohio, they did whatever was necessary to improve their lot in life. It is said that Victoria was a prostitute for a while to earn extra money. No matter what the details, she and Tennessee started Woodhull, Claflin and Company in 1870 with backing from Cornelius Vanderbilt. -

Nsanders, 8Everlv Educational Equity Act Program. 74P.: For,Relatea Documenti, See SO 012 593-594 and (Groups): *Reconstruction

r DOCUMENT DESIIME ED 186 342 ,S0 012595'. AUTHOR NSanders, 8everlv , TITLE Women in American History: A Series. Book Three,- Womenk'during and after the Civil War 1860.r1890. INSTITUTION AmeriCan Federaticin of TeaChers, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGSNCY 'Office of -Pducaticn (DHEW),.WashAngton, D.C. Womemusr Educational Equity Act Program. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 74p.: For,relatea documenti, see SO 012 593-594 and ,ISID 012 596. I AVAILABLE FROM Education Devillopment. Center, 5S,Chapel Street, Newtonc MA 02`160 ($1.50 plus $1-.30 shippimg Set charge) . EDRS PR/CE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available'frpm EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Civil WaT (United°States) :*Females; Teminism; .4Learaing Activities: Occupations; Organizations (Groups): *Reconstruction Era: Secondary Educatio; Sex Discrimination: *Sex Role; Slavery; Sccial Action: Social Studies; Teachers; United States History; Womens Educatipn: *Womens Studies ABSTRACT The document, one in a series og four on women in American history, discusses the role of women during and after the Civil War' (1860-1890). Designed to supplement high school U.S. ,historYitextboks, the book is comprised of five.charters. glapter a describes the work of Union and Confederate wcmen ln the Civil W. Topics include the army nursing service, women in the militarYi'and - women who assumed the responsibilities of their absent husbahds. Chapter.II focuses on black and wfiite women educators for the freed slaves duritg the Reconstruction Era. Excerpts from diaries reveal the experiences of these teachers. Chapter III describes woien on.the western frontier. Again, excerpts from letters and diaries depict the °fewis and tlark guide, Sacalawea: pioneer missionaries adjusting to frontier life: and the experiences of women on the Western trail. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

Reuben Buckman

1 Reuben Buckman “Buck” Claflin Born about 1796 in Massachusetts.1 Died 19 November 1885, Kensington, London, Middlesex, England.2 Buried 24 November 1885, Highgate Cemetery West, London, Middlesex, England3 Buck was the son of Robert Claflin and Anna Underwood.4 No record of his birth has been found but most census enumerations identify Massachusetts as his place of birth and allow for a near calculation of his birth year.5 It is known that his grandfather and father had been in Westhampton, in Hampshire County, then they were in the Sandisfield area of what became Berkshire County where some of the family lived out their lives. Buck’s father later moved to Troy, Bedford County, Pennsylvania around 1800. The complex borders between Hampshire, Hampden, and Berkshire Counties in Massachusetts, together with New York’s Columbia County and Connecticut’s Harford County have frustrated genealogists for years. This coupled with the difficulties in this area following the Revolution,6 make establishing genealogical evidence extremely difficult and time-consuming. There is no doubt that Buck has the worst reputation of anyone involved in the Woodhull story and has become a grotesque caricature.7 There is also no doubt he was a many-faceted individual, often an opportunist, with an entrepreneurial bent. Buck certainly had his faults, but it must be remembered he was the father of, and had a life- long relationship with, two of the most remarkable women of the Gilded Age, Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin. His modern reputation of a conniving, child abusing, snake-oil-peddling, petty thief, and con man all come from Woodhull’s biography by Theodore Tilton. -

(Hummel) Claflin

Roxanna (Hummel) Claflin Born about 1802-1808 in Youngstown, PA1 Died 10 June 1889 in Doughty House, Richmond, Surrey, England.2 Buried 12 June 1889 in Highgrove Cemetery West.3 Grandmothers memory was prodigious She could repeat the bible backwards If you quoted the bible incorrectly she could put your right chapter & verse The world is working out its curses through my family What brought in the sinning relatives Descended from one Margaret --Zula Maud Woodhull4 As the matriarch of the Claflin family, Roxanna, or Anna, Hummel was by far the most emotionally fragile member of the family, yet she was an ever-present and central character in the drama of her children’s lives. Although she was illiterate, she had a sharp memory, as evidenced by Zula Woodhull’s reminiscence, above. Her daughter, Victoria, was also said to have had a similar ability of total recall. Anna was the family member who least understood of her daughters’ (Tennessee and Victoria) embracement of the free-love movement. Always reacting emotionally, she would not accept, and devoted her life to, countermanding their philosophies at every chance. Anna was the one who was primarily responsible for the destruction of the marriage of her daughter, Victoria, with Col. James H. Blood as she doggedly hounded both him and her and railed against their politically radical positions. A deeply religious woman, Anna was like many of the time who were shocked and scandalized by the much- misunderstood free love beliefs. In the end, she did win, when a physically and mentally exhausted Victoria capitulated and divorced Blood. -

Dedication Planned for New National Suffrage Memorial

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY ALLIANCE Women Win the Vote Before1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 1920 & Beyond You're Invited! Celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote Learn What’s Happening in Your State and Online HROUGHOUT 2020, Americans will celebrate the Tcentennial of the extension of the right to vote to women. When Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919, and 36 states ratified it by August 1920, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Now there are local, state and national centennial celebrations in the works including shows and © Trevor Stamp © Trevor parades, parties and plays, films The Women’s Suffrage Centennial float in the Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, was seen by millions on January 1, 2020. On the float were the and performers, teas and more. descendants of suffragists including Ida B. Wells, Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Ten rows of Learn more, get involved, enjoy the ten women in white followed, waving to the crowd. Trevor Stamp photo. activities, and recognize as never before that women’s hard fought Dedication Planned for New achievements are an important part of American history. National Suffrage Memorial HE TURNING POINT Suffra- were jailed over 100 years ago. This gist Memorial, a permanent marked a critical turning point in suffrage Inside This Issue: tribute to the American women’s history. Great Resources T © Robert Beach suffrage movement, will be unveiled on Spread over an acre, the park-like A rendering of the Memorial August 26, 2020 in Lorton, Virginia. -

Centennial Events Planned in Communities Across the Country

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY ALLIANCE Women Win the Vote Before1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 1920 & Beyond You're Invited! Celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote Learn What’s Happening in Your State HROUGHOUT 2019 and 2020, Americans will Tcelebrate the centennial of the extension of the right to vote to women. When Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919, and 36 states ratified it by August 1920, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Now there are local, state and national centennial celebrations in the works including shows and parades, parties and plays, films © Ann Altman and performers, teas and more. Learn more, get involved, enjoy the activities, and recognize as never Centennial Events Planned in before that women’s hard fought achievements are an important part Communities Across the Country of American history. OR MORE THAN a year, women amendment in June 2019, some states Inside This Issue: throughout the country have been have been commemorating their Fmeeting, planning and organizing legislature’s ratification 100 years ago Great Resources for the 2020 centennial of women with official proclamations, historical winning the right to vote. The focal reenactments, exhibits, events and more. Tahesha Way, New Jersey Secretary of 100 Suffragists point is passage of the 19th Amendment, There is a wealth of material available State, at the Alice Paul Institute during a Spring 2019 press conference on state African American celebrated on Equality Day, August 26, here and online which will help you stay suffrage centennial plans.