The Arthaśāstra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 by Karthik Rao Cavale Bachelors

The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 By Karthik Rao Cavale Bachelors of Technology (B.Tech) Indian Institute of Technology Madras Masters in City and Regional Planning (M.C.R.P.) Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2020 © 2020 Karthik Rao Cavale. All Rights Reserved The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author_________________________________________________________________ Karthik Rao Cavale Department of Urban Studies and Planning December 12, 2019 Certified by _____________________________________________________________ Professor Balakrishnan Rajagopal Department of Urban Studies and Planning Dissertation Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________ Associate Professor Jinhua Zhao Chair, PhD Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning 2 The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 by Karthik Rao Cavale Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on December 12, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Studies ABSTRACT This dissertation advances a critique of the "planetary urbanization" thesis inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s writings on capitalist urbanization. Theoretically, it argues that Lefebvrian scholars tend to conflate two distinct meanings of urbanization: a) urbanization understood simply as the territorial expansion of certain kinds of built environment associated with commodity production; and b) urbanization as the reproduction of capitalist modes of production of space on an expanded, planetary scale. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1884, 14/01/2019

Trade Marks Journal No: 1884, 14/01/2019 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[mauMba[---- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. fO@sa : 022 24140808 Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel:022-24140808 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1884, 14/01/2019 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaakayaa----layalaya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaahsalaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kayakaya---- Operation Tatkal saavasaava----jainakjainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt AAavaodnaavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1884, 14/01/2019 vaga- / Class - 1 11-116 vaga- / Class - 2 117-137 vaga- / Class - 3 138-360 vaga- / Class - 4 361-395 vaga- / Class - 5 396-1465 vaga- / Class - 6 1466-1556 vaga- / Class - 7 1557-1688 vaga- / Class - 8 1689-1717 vaga- / Class - 9 1718-2060 vaga- / Class - 10 2061-2092 vaga- / Class - 11 2093-2267 vaga- -

History Part 24 Notes

Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 History Part – 24 24] Sethupathi Rule Notes Sethupathis of Ramnad and Sivaganga The rulers of Ramnad and Sivaganga region of early l7th Century were called Sethupathi’s. The Nayak ruler Muthukrishnappa Nayak reestablished the ancient line of sethupathys who were the chieftains under the pandyas in the beginning of 17th century as protector and guardian of the pilgrims to Sethusamudram and Rameswaram. The protector of Sethusamudram was called as Sethupathy. Sadaikkathevar was a loyal subordinate of the Nayaks. He emerged as the chief of the poligas. Sethupathis were maravas of Ramnad, Madurai and Tirunelveli. They had Ramnad as their official headquarters. Sadaikkathevar and his son KuttanSethupathi acted as Sethupathis and extended protection to the pilgrims who visited Rameswaram. 1 www.winmeen.com | Learning Leads to Ruling Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 Apart from giving protection two Sethupathis did religious services to the Ramanathaswamy temple at Rameswaram. Sadaikka Thevar (1636 AD To 1645 )AD Kuttan Sethupathi made his adopted son Sadaikkathevar II as the next ruler. This was opposed by Kuttan Sethupathi’s natural son Thambi, Thirumalai Nayak supported the claim of Thambi. The ruler Sadaikka thevar was dethroned and jailed. Thambi was made as Sethupathi. Thambi was not competent. Sadaikkathevar’s nephews Raghunathathevar and Narayanathevar rebelled against Thambi’s rule. Accepting the popular representation, Thirumalai Nayak released Sadaikkathevar from Jail and made him Sethupathi after dismissing Thambi from the throne Sadiakkathevar constructed a new Chokkanatha temple at Rameswaram. He did lot of Charitable and public works. 2 www.winmeen.com | Learning Leads to Ruling Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 Raghunatha Sethupathi (1645 AD to 1670 AD) Raghunatha sethupathi was loyal to the Nayak ruler. -

NATIONAL BOARD of ACCREDITATION (NBA) List of Accredited Programmes in Technical Institutions

NATIONAL BOARD OF ACCREDITATION (NBA) List of Accredited Programmes in Technical Institutions STATE : ANDHRA PRADESH Name of the Level of Period of Status Sl.No. Programmes Institutions Programmes Validity effective from 1. Adams Engg. College Electronics & Commu. Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Seetharamapatnam, Computer Science & Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Paloncha-507115, Electrical & Electronics Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Khammam District, AP Mechanical Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 2. Al-Habeeb College of Electrical & Electronics Engg. UG 3 years May 05, 2009 Engg. & Tech., R.R. Computer Science & Engg. UG 3 years May 05, 2009 Distt., AP 3. Anil Neerukanda Inst. of Electrical & Electronics Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Tech. & Science, Computer Science & Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Visakhapatnam Electronics & Comm. Engg. UG 3 years July 19, 2008 Bio-Technology UG 3 years July 19, 2008 4. Annamacharya Institute of Mechanical Engg. (†) UG 3 Yrs April 16, 2009 Technology & Sciences, Electrical & Electronics Engg. UG 3 Yrs April 16, 2009 Thallapaka (Panchayath), Electronics & Commu. Engg. UG 3 Yrs April 16, 2009 New Boyanapalli (Post), Computer Science & Engg. UG 3 Yrs April 16, 2009 Rajampet (Mandal), Information Technology UG 3 Yrs April 16, 2009 Kadapa Distt., Andhra Pradesh – 516 126 5. Anurag Engg. College, Information Technology UG 3 years Feb. 10, 2009 kodad, Nalgonda, A.P. Electrical & Electronics Engg. UG 3 years Feb. 10, 2009 Electronics & Comm. Engg. UG 3 years Feb. 10, 2009 Computer Science & Engg. UG 3 years Feb. 10, 2009 6. Bapatla Engineering Mechanical Engineering (†) UG 3 Years March 16, 2007 College, Baptla, Gunture, Chemical Engineering UG 3 Years March 16, 2007 AP Electronics & Instru. -

Handicraft Survey Report Conchshell Products , Part X D, Series-23, West

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-23 WEST BENGAL PART X-D HANDICRAFT SURVEY REPORT CONCHSHELL PRODUCTS Investigation and Draft: DIPANKAR SEN Editing and Guidance: SUKUMAR SINHA HANDICRAFT SURVEY REPORT , CONCHSHELL PRODUCTS Assistance in Investigation and Tabulation: Sri Sanat :Kumar Saba, Assistant Compiler Preparation of Map: Sri Subir Kumar Chatterjee, DraftsmaJi Preparation of Sketches; Sri B. N. Mullick, Senior Artist Photosraphy: Sri Arunabha Dutta, Investigatf,):r FOREWORD The Indian handicrafts are known the world over for their rich variety, grace, elegance and skilled craftsmanship. Nevertheless, a number of handicrafts because of their stiff compe tition with factory made products, non-availability of raw materials, exhorbitant increase in the manufacturing cost, lack of proper marketing facilities for finished products or due to a variety of other reasons have either become extinct or have reached the moribund stage. After independence, however, a number of schemes were introduced by different govern ment agencies for their growth and development but still this sudden impetus have helped only a few crafts to flourish and thereby becomes spinners of foreign exchange for the country. Despite the unique position being enjoyed by the handicrafts especially in the realm of national economy, the general awareness among the people in the country about our crafts and craftsmen had been deplorably poor. Nothing was practically known about the commodities produced, techniques employed for the manufacture of different" objects, raw materials used, their availability, methods adopted for the sale of finished products, etc. An attempt was therefore made in connection with the 1961 Census to study about 150 crafts from different parts of the country with a view to provide basic information on those crafts which were selected for the study. -

THE MOPLAH REBELLION OP 1921-22 and ITS GENESIS CONRAD WOOD School of Oriental and African Studies Thesis Submitted to the Unive

THE MOPLAH REBELLION OP 1921-22 AND ITS GENESIS CONRAD WOOD School of Oriental and African Studies Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1975 ProQuest Number: 11015837 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015837 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is an attempt to interpret the rebellion staged in 1921-22 by part of the Muslim community of the Malabar District of the Madras Presidency, a community known as the 'Moplahs' or ♦Mappillas'. Since, it is here argued, this challenge to British rule was a consequence of the impact of that power on social relations in rural Malabar starting with the earliest period of British control of the area, the genesis of the rising is traced from the cession of Malabar to the East India Company in 1792. Chapter 1 constitutes an investigation both of social relations in rural Malabar under the impact of British rule and of the limits of Moplah response under conditions in which rebellion was impracticable. -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address

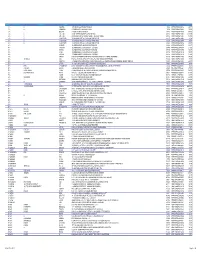

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 AK AGRAWAL 110 D M C D COLONY AZADPUR DELHI 110033 0000000000CEA0018033 240.00 2 A K PARBHAKAR 8 SCHOOL BLOCK SHAKARPUR DELHI 110092 0000000000CEA0018043 750.00 3 A GROVER 2-A GOKHLE MARG LUCKNOW 226001 0000000000CEA0018025 645.00 4 A D KODILKAR 58/1861 NEHRUNAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000CEA0018011 1,125.00 5 A D KODILKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000CEA0018012 180.00 6 A M RAJAPURKAR 11 CHANCHAL APPT SANGHVI NAGAR AUNDH PUNE 411007 0000000000CEA0018056 225.00 7 A M RAJAPURKAR 11 CHANCHAL APTS SANGHVI NAGAR AVNDH PUNE 411007 0000000000CEA0018057 240.00 8 A M RAJAPURKAR 11 CHANCHAL APTS SANGHVI NAGAR AUNDH PUNE 411007 0000000000CEA0018058 240.00 9 A GIRIDHAR 125 ANNAM GARDEN KAVADIGUDA HYDERABAD 500003 0000000000CEA0018021 255.00 10 A KARISHMA 125 ANNAM GARDENS KAVADIGUDA HYDERABAD 500003 0000000000CEA0018050 510.00 11 A MEGHNA 125 ANNAM GARDON KAVADIGUDA HYDERABAD 500003 0000000000CEA0018066 255.00 12 A VIKYAT 125 ANNAM GARDENS KAVADIGUDA HYDERABAD 500003 0000000000CEA0018106 255.00 13 A VINDHYA 125 ANNAM GARDENS KAVADIGUDA HYDERABAD 500003 0000000000CEA0018109 510.00 14 A SARADA FLAT NO 202 PREMIER COURT APPTS GOLKONDA X ROADS MUSHIRABAD HYDERABAD 500020 0000000000CEA0018089 750.00 15 A SRINIVASA RAO FLAT NO 202 KRISHNA ENCLAVE PLOT NO F-64 MADHURANAGAR HYDERABAD 500038 0000000000CEA0018092 240.00 16 A GAYATHRI C/O M MADHVESACHAR PLOT NO 41, MIG PHASE-I H NO 6-4-9, VANASTHALIPURAM HYDERABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 500070 0000000000CEA0018019 -

Unpaid-Dividend-31St

STATEMENT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND AS ON 25.08.2018, DECLARED AT THE AGM OF THE COMPANY HELD ON 20TH JULY, 2018 ( AS PER THE PROVISION OF THE U/S. 124(2) OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2013 Folio/ DP. ID./ CL. ID. Dividend Amount (Rs.) Name of Shareholder Address 0000009 MR ASHWANI CHOUDHRY 292.50 A-3/85 JANAKPURI,NEW DELHI,110058 0000010 MRS KANTA CHAUDHRY 292.50 A-3/85 JANAKPURI,NEW DELHI,110058 0000011 MR SHIVINDER SINGH 292.50 A-3/85 JANAKPURI,NEW DELHI,110058 0000047 MR RAJINDER KUMAR SACHDEVA 877.50 1405 DR MUKERJEE NAGAR,DELHI,110009 0000081 MISS SHVETA AJMANI 650.00 WZ 108 A/I,BASAI DARAPUR,MOTI NAGAR,NEW DELHI,110015 0000133 MRS VEERAN 292.50 2300 SECTOR 23 C,CHANDIGARH,160023 0000276 MR ANIL KUAMR SONI 325.00 6 ARJUN NAGAR P O SAFDAR JUNG,ENCLAVE,NEW DELHI, ,110029 0000292 MISS SHALU BANSAL 97.50 C-76 ASHOK VIHAR PHASE-I,DELHI,110052 0000293 MR RISHI KUMAR BANSAL 97.50 C-76 ASHOK VIHAR PHASE-1,DELHI,110052 0000346 MRS DEEPIKA KAPOOR 585.00 D-6/17 VASANT VIHAR,NEW DELHI,110057 0000354 MR RAJ KUMAR 325.00 5592 NEW CHANDRAWAL (1ST FLOOR),OPP BACHOOMAL AGARWAL PRY SCHOOL,KAMLA NAGAR DELHI, ,110007 0000359 MRS LATA KURAL 260.00 C-22 MANSAROVAR PARK,SHAHDARA DELHI,110032 0000367 MRS SANTOSH MADHOK 877.50 4/3 SHANTI NIKETAN,NEW DELHI,110021 0000370 MR PRAN NATH KOHLI 195.00 1825 LAXMI NAVAMI STREET,NR IMPERIAL CINEMA,PAHARGANJ,NEW DELHI,110055 0000381 MRS ASHA RANI JERATH 585.00 SECTOR 7A HOUSE NO 25,FARIDABAD,121002 0000383 SANJAY KUMAR ARYA 292.50 89/3 RAMGALI VISHWAS NAGAR,SHAHDARA DELHI,110032 0000388 MISS SADHNA 292.50 E-30 LAJPAT NAGAR-IST,NEW -

' Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

’ Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK No one can hope to make any effective mark upon his time and bring the aid that is worth bringing to great principles and struggling causes if he is not strong in his love and his hatred. I hate injustice, tyranny, pompousness and humbug, and my hatred embraces all those who are guilty of them. I want to tell my critics that I regard my feelings of hatred as a real force. They are only the reflex of the love I bear for the causes I believe in. —Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in his Preface to ‘Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 5 Compiled by Vasant Moon Editorial Sub-committee Dr. P. T. Borale Dr. B. D. Phadke Shri S. S. Rege Shri Daya Pawar Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 5 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : 14 April, 1989 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. -

Newly Recruited Forester Allotted Circle / Division TAMIL NADU FOREST DEPARTMENT

TAMIL NADU FOREST DEPARTMENT Newly Recruited Forester allotted Circle / Division Name Sl.No Reg.No Address Gender Allotted Circle Allotted Division (Thiruvargal) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 THAMODHARAN R 18010000069 183 MALE Thanjavur Thiruvarur PONNINAGAR,PUNGANUR,RAMJINAG Division, AR Thiruvarur POST,SRIRANGAM,TIRUCHIRAPPALLI, TAMILNADU,620009 2 THAMILARASAN S 18010000467 5 252 NEAR MGR MALE Dharmapuri Dharmapuri STATUE,KOMALIVATTAM,SUKKAMPAT Division, TY Dharmapuri POST,SALEM,SALEM,TAMILNADU,6361 22 3 SRINIVASAN A 18010000560 422 AMBETHKAR MALE Salem Salem Division, STREET,VENKATASAMUDRAM Salem PO,PAPPIREDDIPATTI TK,PAPPIREDDIPATTI,DHARMAPURI,T AMILNADU,636905 4 SANDHIYA SHREE B 18010000569 577 PATCHUR MAIN FEMALE Vellore Thiruvannamalai ROAD,NATTRAMPALLI,TIRUPATTUR Division, TALUK,TIRUPATTUR,VELLORE,TAMILN Thiruvannamalai ADU,635854 5 SIVACHANDIRAN S 18010000584 02 KALAINGAR KARUNANITHI MALE Villupuram Cuddalore STREET,KONDANGI,,VILLUPPURAM,VI Division, LLUPURAM,TAMILNADU,605301 Cuddalore 6 GOKUL K 18010000628 1 125 VEERABATHIRAN KOVIL MALE Salem Salem Division, STREET,A.PALLIPATTI Salem POST,PAPPIREDDIPATTI TALUK,PAPPIREDDIPATTI,DHARMAPU RI,TAMILNADU,636905 7 SAKTHIVEL T 18010003069 203 359 VELLALAR MALE Dharmapuri Wildlife Division, SREET,KODAMBAKADU,NETHIMEDU,S Hosur ALEM,SALEM,TAMILNADU,636002 8 DIVYA S 18010003815 2 3 380 VALANESAM,PUDHUPUTHOOR FEMALE Madurai Madurai Division, POST,KODAIKANAL,KODAIKANAL,DIN Madurai DIGUL,TAMILNADU,624103 9 MUTHUKUMAR 18010003822 1 25 KANNANTHOTTAM,ANIYAR MALE STR, Erode Erode Division, KOLANDAPALLAYAM Erode -

THE INSTITUTION of ENGINEERS (INDIA) LIST of INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS Updated on : December 11, 2019

THE INSTITUTION OF ENGINEERS (INDIA) LIST OF INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS Updated On : December 11, 2019 SLNO INSTITUTE_NAME ADDRESS PIN MEMBCODE 1 (D & S CELL) KASHMIR HOUSE P O DHQ NEW DELHI 110011 IM0000371 2 A M C COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING 18TH K M, BANNERGATTA ROAD KALKERE BANGALORE 560083 IM0001548 3 A V C COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING MANNAMPANDAL MAYILADUTHURAI DIST NAGAI T N 609305 IM0001365 4 AALIM MUHAMMED SALEGH COLLEGE NIZARA EDUCATIONAL CAMPUS OF ENGINEERING MUTHAPUDUPET AVADI IAF 600055 IM0001289 5 ABES ENGINEERING COLLEGE CAMPUS 1 19TH KM STONE 201009 IM0005381 6 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY PO AEDCONAGAR ADISAPTAGRAM 712121 IM0001890 7 ACS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING 207, KAMBIPURA, MYSURU ROAD, NEXT TO KENGERI, BENGALURU 560074 IM0003494 8 ADDYUTHIYA POWER PROJECTS (P) LTD 52/1582 A2, INDIVARAM, EXCEL PARK FATHIMA CHURCH ROAD 682020 IM0004741 9 ADHIPARASAKTHI ENGINEERING MELMARUVATHUR CHEYYUR T K COLLEGE DIST KANCHIPURAM 603319 IM0001262 10 ADHIYAMAAN COLLEGE OF DR. M.G.R. NAGAR, HOSUR ENGINEERING 635109 IM0002811 11 ADI SHANKARA INSTITUTE OF ENGG AND VIDYA BHARATHI NAGAR TECH KALADY 683574 IM0004784 12 ADICHUNCHANAGIRI INSTITUTE OF CHIKMAGALUR TECHNOLOGY KARNATAKA 577102 IM0001025 13 ADITYA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & ADITYA NAGAR ADB ROAD TECH SURAMPALEM GANDEPALLI MANDAL 533437 IM0005438 14 ADITYA INST OF TECHNOLOGY & K KOTTURU (POST), TEKKALI (MANDALAM) MANAGEMENT SRIKAKULAM (DISTRICT) 532201 IM0004202 15 AGNI COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY OFF OLD MAHABALIPURAM ROAD THALAMBUR, CHENNAI 600130 IM0003664 16 AHALIA SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING & KOZHIPPARA (PO) TECHNOLOGY -

Essays on Tradi...Rtf

DHARAMPAL • COLLECTED WRITINGS Volume V ESSAYS ON TRADITION, RECOVERY AND FREEDOM 1 DHARAMPAL • COLLECTED WRITINGS Volume I Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century Volume II Civil Disobedience in Indian Tradition Volume III The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century Volume IV Panchayat Raj and India’s Polity Volume V Essays on Tradition, Recovery and Freedom 2 ESSAYS ON TRADITION, RECOVERY AND FREEDOM by Dharampal Other India Press Mapusa 403 507, Goa, India 3 Essays on Tradition, Recovery and Freedom By Dharampal This work is published as part of a special collection of Dharampal’s writings, by: Other India Press Mapusa 403 507, Goa, India. Copyright © (2000) Dharampal Cover Design by Orijit Sen Distributed by: Other India Bookstore, Above Mapusa Clinic, Mapusa 403 507 Goa, India. Phone: 91-832-263306; 256479. Fax: 91-832-263305 OIP policy regarding environmental compensation: 5% of the list price of this book will be made available by Other India Press to meet the costs of raising natural forests on private and community lands in order to compensate for the partial use of tree pulp in paper production. ISBN No.: 81-85569-49-5 (HB) Set ISBN No.:81-85569-50-9 (PB) Set Printed by Sujit Patwardhan for Other India Press at MUDRA, 383 Narayan, Pune 411 030, India. 4 Publisher’s Note Volume V comprises five essays by Dharampal which not only deal with some of the themes covered in the earlier volumes, but also place them within a broad philosophical perspective. Some of these essays are actually lectures delivered by him before audiences in Pune, Bangalore and Lisbon.