Chinese Medicine and the Problem of Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Michèle Boin, Elvire Eijkman, Katrien Polman, Tineke Sommeling, Marlene C.A

African Studies Abstracts Online: number 21, 2008 Boin, M.; Eijkman, E.M.; Polman, K.; Sommeling, C.M.; Doorn, M.C.A. van Citation Boin, M., Eijkman, E. M., Polman, K., Sommeling, C. M., & Doorn, M. C. A. van. (2008). African Studies Abstracts Online: number 21, 2008. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12884 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Leiden University Non-exclusive License: license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12884 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Number 21, 2008 AFRICAN STUDIES ABSTRACTS ONLINE Number 21, 2008 Contents Editorial policy............................................................................................................... iii Geographical index ....................................................................................................... 1 Subject index................................................................................................................. 3 Author index.................................................................................................................. 7 Periodicals abstracted in this issue............................................................................... 14 Abstracts ....................................................................................................................... 18 Abstracts produced by Michèle Boin, Elvire Eijkman, Katrien Polman, Tineke Sommeling, Marlene C.A. Van Doorn ii EDITORIAL POLICY African Studies Abstracts -

Kahlil Gibran a Tear and a Smile (1950)

“perplexity is the beginning of knowledge…” Kahlil Gibran A Tear and A Smile (1950) STYLIN’! SAMBA JOY VERSUS STRUCTURAL PRECISION THE SOCCER CASE STUDIES OF BRAZIL AND GERMANY Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan P. Milby, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin Adelman, Adviser Professor William J. Morgan Professor Sarah Fields _______________________________ Adviser College of Education Graduate Program Copyright by Susan P. Milby 2006 ABSTRACT Soccer playing style has not been addressed in detail in the academic literature, as playing style has often been dismissed as the aesthetic element of the game. Brief mention of playing style is considered when discussing national identity and gender. Through a literature research methodology and detailed study of game situations, this dissertation addresses a definitive definition of playing style and details the cultural elements that influence it. A case study analysis of German and Brazilian soccer exemplifies how cultural elements shape, influence, and intersect with playing style. Eight signature elements of playing style are determined: tactics, technique, body image, concept of soccer, values, tradition, ecological and a miscellaneous category. Each of these elements is then extrapolated for Germany and Brazil, setting up a comparative binary. Literature analysis further reinforces this contrasting comparison. Both history of the country and the sport history of the country are necessary determinants when considering style, as style must be historically situated when being discussed in order to avoid stereotypification. Historic time lines of significant German and Brazilian style changes are determined and interpretated. -

Protest at the Pyramid: the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Protest at the Pyramid: The 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B. Witherspoon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PROTEST AT THE PYRAMID: THE 1968 MEXICO CITY OLYMPICS AND THE POLITICIZATION OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES By Kevin B. Witherspoon A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kevin B. Witherspoon defended on Oct. 6, 2003. _________________________ James P. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member _________________________ Valerie J. Conner Committee Member _________________________ Robinson Herrera Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the help of many individuals. Thanks, first, to Jim Jones, who oversaw this project, and whose interest and enthusiasm kept me to task. Also to the other members of the dissertation committee, V.J. Conner, Robinson Herrera, Patrick O’Sullivan, and Joe Richardson, for their time and patience, constructive criticism and suggestions for revision. Thanks as well to Bill Baker, a mentor and friend at the University of Maine, whose example as a sports historian I can only hope to imitate. Thanks to those who offered interviews, without which this project would have been a miserable failure: Juan Martinez, Manuel Billa, Pedro Aguilar Cabrera, Carlos Hernandez Schafler, Florenzio and Magda Acosta, Anatoly Isaenko, Ray Hegstrom, and Dr. -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways. -

Ordinary Culture in a World of Strangers: Toward Cosmopolitan Cultural Policy

International Journal of Cultural Policy ISSN: 1028-6632 (Print) 1477-2833 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcul20 Ordinary culture in a world of strangers: toward cosmopolitan cultural policy Christiaan De Beukelaer To cite this article: Christiaan De Beukelaer (2017): Ordinary culture in a world of strangers: toward cosmopolitan cultural policy, International Journal of Cultural Policy, DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1389913 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1389913 Published online: 23 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcul20 Download by: [75.166.28.148] Date: 23 October 2017, At: 07:23 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CULTURAL POLICY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1389913 Ordinary culture in a world of strangers: toward cosmopolitan cultural policy* Christiaan De Beukelaer School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The image of Zwarte Piet, as part of Dutch Sinterklaas celebrations has caused Received 19 April 2017 heated debate in the past decade, which has polarized tensions between the Accepted 5 October 2017 ‘Dutch’ and ‘strangers’. This article argues that the debate cannot be resolved KEYWORDS within a framework of a methodologically nationalist cultural policy. Building Cultural policy; on Kwame Anthony Appiah’s book Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of cosmopolitanism; Strangers, I argue that a cosmopolitan framework for belonging is not only multiculturalism; Zwarte Piet; a normative but also a policy imperative. -

Tradition, Christianity, and the State in Understandings of Sickness and Healing in South Nias, Indonesia

TRADITION, CHRISTIANITY, AND THE STATE IN UNDERSTANDINGS OF SICKNESS AND HEALING IN SOUTH NIAS, INDONESIA by Edward Peake Thesis submitted for degree of PhD Department of Anthropology London School of Economics University of London September 2000 UMI Number: U126970 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126970 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7202 7 3 8 3 9 % ABSTRACT TRADITION, CHRISTIANITY, AND THE STATE: UNDERSTANDINGS OF SICKNESS AND HEALING IN SOUTH NIAS, INDONESIA The thesis describes the range of south Nias villagers' understandings of sickness and healing, and investigates how and why they draw on various cultural spheres in the interpretation and management of sickness events. Traditional notions of sickness etiology are set in the context of both Christian beliefs and the state's efforts to promulgate modem, 'scientific' understandings, in order to show how sociologically distinguished individuals draw variously at different times and contexts on all three fields of sickness interpretation and management. The thesis begins with a history of Nias relations with the outside world, in order to delineate the genealogy of modem Indonesian attitudes to local culture. -

Stockcar Racing As Contextual Tradition

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 7-2006 A “Southern Tradition?”: Stockcar Racing as Contextual Tradition Patrick A. Lindsay Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lindsay, Patrick A., "A “Southern Tradition?”: Stockcar Racing as Contextual Tradition" (2006). Master's Theses. 1416. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1416 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “SOUTHERN TRADITION?”: STOCKCAR RACING AS CONTEXTUAL TRADITION by Patrick A. Lindsay A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan July 2006 A “SOUTHERN TRADITION?”: STOCKCAR RACING AS CONTEXTUAL TRADITION Patrick Lindsay, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2006 A large number of academics who have examined stockcar racing have concluded that stockcar racing is a “Southern tradition.” While the implicit definitions of tradition may vary, many generally agree that there is a clear historical relationship between stock car racing and the South. It is my contention that the idea that stockcar racing is a “Southern” tradition does not represent the reality of stockcar racing fandom for many people outside of the South. I assert that stock car racing is instead a “contextual tradition”, a practice that became labeled a tradition through specific historical and cultural circumstances. -

History and Religion Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche Und Vorarbeiten

History and Religion Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten Herausgegeben von Jörg Rüpke und Christoph Uehlinger Band 68 History and Religion Narrating a Religious Past Edited by Bernd-Christian Otto, Susanne Rau and Jörg Rüpke with the support of Andrés Quero-Sánchez ISBN 978-3-11-044454-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044595-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-043725-6 ISSN 0939-2580 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ∞ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents Historyand Religion 1 Section I Origins and developments Introduction 21 Johannes Bronkhorst The historiography of Brahmanism 27 Jörg Rüpke Construing ‘religion’ by doinghistoriography: The historicisation of religion in the Roman Republic 45 Anders Klostergaard Petersen The use of historiography in Paul: Acase-study of the instrumentalisation of the past in the context of Late Second Temple Judaism 63 Ingvild Sælid Gilhus Flirty fishing and poisonous serpents: Epiphanius of Salamis inside his Medical chestagainstheresies 93 Sylvie Hureau Reading sutras in biographies of Chinese Buddhist monks 109 Chase F. Robinson Historyand -

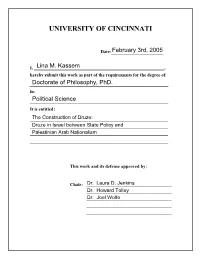

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

Judicial Reconstruction and the Rule of Law International Humanitarian Law Series

Judicial Reconstruction and the Rule of Law International Humanitarian Law Series VOLUME 39 Editors-in-Chief H.E. Judge Sir Christopher Greenwood Professor Timothy L.H. McCormack Editorial Advisory Board Professor Georges Abi-Saab H.E. Judge George H. Aldrich Madame Justice Louise Arbour Professor Ove Bring Professor John Dugard Professor Dr. Horst Fischer Dr. Hans-Peter Gasser H.E. Judge Geza Herczegh Professor Frits Kalshoven Professor Ruth Lapidoth Professor Gabrielle Kirk McDonald H.E. Judge Th eodor Meron Captain J. Ashley Roach Professor Michael Schmitt Professor Jiří Toman Th e International Humanitarian Law Series is a series of monographs and edited volumes which aims to promote scholarly analysis and discussion of both the theory and practice of the international legal regulation of armed confl ict. Th e series explores substantive issues of International Humanitarian Law including, – protection for victims of armed confl ict and regulation of the means and meth- ods of warfare – questions of application of the various legal regimes for the conduct of armed confl ict – issues relating to the implementation of International Humanitarian Law obli- gations – national and international approaches to the enforcement of the law and – the interactions between International Humanitarian Law and other related areas of international law such as Human Rights, Refugee Law, Arms Control and Disarmament Law, and International Criminal Law. Th e titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ihul Judicial Reconstruction and the Rule of Law Reassessing Military Intervention in Iraq and Beyond by Angeline Lewis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, Angeline. -

The Invention of Tradition

The Invention of Tradition Edited by ERIC HOBSBA WM and TERENCE RANGER .:... ,.;.,.CAMBRIDGE - ::: UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarc6n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © E. J. Hobsbawm 1983 © Hugh Trevor-Roper 1983 © Prys Morgan 1983 © David Cannadine 1983 © Bernard S. Cohn 1983 © Terence Ranger 1983 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1983 First paperback edition 1984 Reprinted 1985,1986, 1987, 1988, 1989 Canto edition 1992 Reprinted 1993,1994,1995,1996,1997,1999,2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Library of Congress Catalogue card number: 82-14711 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data The invention of tradition- (Past and present publications) 1. Sociology 2. Folklore- History I. Hobsbawm, E. J. II. Ranger, Terence Ill. Series 303.3'72 HM201 ISBN 0 521 43773 3 paperback Cover illustration: Car! Haag, Evening at Balmoral. Watercolour, 1854. Windsor Castle, Royal Library. © Her Majesty The Queen. Contents Contributors page vi Introduction: Inventing Traditions ERIC HOBS BA WM 2 The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland HUGH TREVOR-ROPER 15 3 From a Death to a View: The Hunt for the Welsh Past in the Romantic Period PRYS MORGAN 43 4 The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the 'Invention of Tradition', c.