Define Term in Logic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotle's Assertoric Syllogistic and Modern Relevance Logic*

Aristotle’s assertoric syllogistic and modern relevance logic* Abstract: This paper sets out to evaluate the claim that Aristotle’s Assertoric Syllogistic is a relevance logic or shows significant similarities with it. I prepare the grounds for a meaningful comparison by extracting the notion of relevance employed in the most influential work on modern relevance logic, Anderson and Belnap’s Entailment. This notion is characterized by two conditions imposed on the concept of validity: first, that some meaning content is shared between the premises and the conclusion, and second, that the premises of a proof are actually used to derive the conclusion. Turning to Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, I argue that there is evidence that Aristotle’s Assertoric Syllogistic satisfies both conditions. Moreover, Aristotle at one point explicitly addresses the potential harmfulness of syllogisms with unused premises. Here, I argue that Aristotle’s analysis allows for a rejection of such syllogisms on formal grounds established in the foregoing parts of the Prior Analytics. In a final section I consider the view that Aristotle distinguished between validity on the one hand and syllogistic validity on the other. Following this line of reasoning, Aristotle’s logic might not be a relevance logic, since relevance is part of syllogistic validity and not, as modern relevance logic demands, of general validity. I argue that the reasons to reject this view are more compelling than the reasons to accept it and that we can, cautiously, uphold the result that Aristotle’s logic is a relevance logic. Keywords: Aristotle, Syllogism, Relevance Logic, History of Logic, Logic, Relevance 1. -

Verifying the Unification Algorithm In

Verifying the Uni¯cation Algorithm in LCF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory Corn Exchange Street Cambridge CB2 3QG England August 1984 Abstract. Manna and Waldinger's theory of substitutions and uni¯ca- tion has been veri¯ed using the Cambridge LCF theorem prover. A proof of the monotonicity of substitution is presented in detail, as an exam- ple of interaction with LCF. Translating the theory into LCF's domain- theoretic logic is largely straightforward. Well-founded induction on a complex ordering is translated into nested structural inductions. Cor- rectness of uni¯cation is expressed using predicates for such properties as idempotence and most-generality. The veri¯cation is presented as a series of lemmas. The LCF proofs are compared with the original ones, and with other approaches. It appears di±cult to ¯nd a logic that is both simple and exible, especially for proving termination. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of uni¯cation 2 3 Overview of LCF 4 3.1 The logic PPLAMBDA :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 3.2 The meta-language ML :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 3.3 Goal-directed proof :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 3.4 Recursive data structures ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 4 Di®erences between the formal and informal theories 7 4.1 Logical framework :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.2 Data structure for expressions :::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.3 Sets and substitutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4.4 The induction principle :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 5 Constructing theories in LCF 10 5.1 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

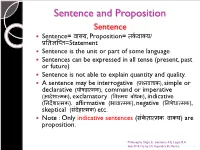

Logic- Sentence and Propositions

Sentence and Proposition Sentence Sentence= वा啍य, Proposition= त셍कवा啍य/ प्रततऻप्तत=Statement Sentence is the unit or part of some language. Sentences can be expressed in all tense (present, past or future) Sentence is not able to explain quantity and quality. A sentence may be interrogative (प्रश्नवाच셍), simple or declarative (घोषड़ा配म셍), command or imperative (आदेशा配म셍), exclamatory (ववमयतबोध셍), indicative (तनदेशा配म셍), affirmative (भावा配म셍), negative (तनषेधा配म셍), skeptical (संदेहा配म셍) etc. Note : Only indicative sentences (सं셍ेता配म셍तवा啍य) are proposition. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 1 All kind of sentences are not proposition, only those sentences are called proposition while they will determine or evaluate in terms of truthfulness or falsity. Sentences are governed by its own grammar. (for exp- sentence of hindi language govern by hindi grammar) Sentences are correct or incorrect / pure or impure. Sentences are may be either true or false. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 2 Proposition Proposition are regarded as the material of our reasoning and we also say that proposition and statements are regarded as same. Proposition is the unit of logic. Proposition always comes in present tense. (sentences - all tenses) Proposition can explain quantity and quality. (sentences- cannot) Meaning of sentence is called proposition. Sometime more then one sentences can expressed only one proposition. Example : 1. ऩानीतबरसतरहातहैत.(Hindi) 2. ऩावुष तऩड़तोत (Sanskrit) 3. It is raining (English) All above sentences have only one meaning or one proposition. -

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis Julian Hartman September 4, 2010 Abstract This paper is intended as an exploration of nonstandard analysis, and the rigorous use of infinitesimals and infinite elements to explore properties of the real numbers. I first define and explore first order logic, and model theory. Then, I prove the compact- ness theorem, and use this to form a nonstandard structure of the real numbers. Using this nonstandard structure, it it easy to to various proofs without the use of limits that would otherwise require their use. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 An Introduction to First Order Logic 2 2.1 Propositional Logic . 2 2.2 Logical Symbols . 2 2.3 Predicates, Constants and Functions . 2 2.4 Well-Formed Formulas . 3 3 Models 3 3.1 Structure . 3 3.2 Truth . 4 3.2.1 Satisfaction . 5 4 The Compactness Theorem 6 4.1 Soundness and Completeness . 6 5 Nonstandard Analysis 7 5.1 Making a Nonstandard Structure . 7 5.2 Applications of a Nonstandard Structure . 9 6 Sources 10 1 1 Introduction The founders of modern calculus had a less than perfect understanding of the nuts and bolts of what made it work. Both Newton and Leibniz used the notion of infinitesimal, without a rigorous understanding of what they were. Infinitely small real numbers that were still not zero was a hard thing for mathematicians to accept, and with the rigorous development of limits by the likes of Cauchy and Weierstrass, the discussion of infinitesimals subsided. Now, using first order logic for nonstandard analysis, it is possible to create a model of the real numbers that has the same properties as the traditional conception of the real numbers, but also has rigorously defined infinite and infinitesimal elements. -

Unification: a Multidisciplinary Survey

Unification: A Multidisciplinary Survey KEVIN KNIGHT Computer Science Department, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-3890 The unification problem and several variants are presented. Various algorithms and data structures are discussed. Research on unification arising in several areas of computer science is surveyed, these areas include theorem proving, logic programming, and natural language processing. Sections of the paper include examples that highlight particular uses of unification and the special problems encountered. Other topics covered are resolution, higher order logic, the occur check, infinite terms, feature structures, equational theories, inheritance, parallel algorithms, generalization, lattices, and other applications of unification. The paper is intended for readers with a general computer science background-no specific knowledge of any of the above topics is assumed. Categories and Subject Descriptors: E.l [Data Structures]: Graphs; F.2.2 [Analysis of Algorithms and Problem Complexity]: Nonnumerical Algorithms and Problems- Computations on discrete structures, Pattern matching; Ll.3 [Algebraic Manipulation]: Languages and Systems; 1.2.3 [Artificial Intelligence]: Deduction and Theorem Proving; 1.2.7 [Artificial Intelligence]: Natural Language Processing General Terms: Algorithms Additional Key Words and Phrases: Artificial intelligence, computational complexity, equational theories, feature structures, generalization, higher order logic, inheritance, lattices, logic programming, natural language -

The Peripatetic Program in Categorical Logic: Leibniz on Propositional Terms

THE REVIEW OF SYMBOLIC LOGIC, Page 1 of 65 THE PERIPATETIC PROGRAM IN CATEGORICAL LOGIC: LEIBNIZ ON PROPOSITIONAL TERMS MARKO MALINK Department of Philosophy, New York University and ANUBAV VASUDEVAN Department of Philosophy, University of Chicago Abstract. Greek antiquity saw the development of two distinct systems of logic: Aristotle’s theory of the categorical syllogism and the Stoic theory of the hypothetical syllogism. Some ancient logicians argued that hypothetical syllogistic is more fundamental than categorical syllogistic on the grounds that the latter relies on modes of propositional reasoning such as reductio ad absurdum. Peripatetic logicians, by contrast, sought to establish the priority of categorical over hypothetical syllogistic by reducing various modes of propositional reasoning to categorical form. In the 17th century, this Peripatetic program of reducing hypothetical to categorical logic was championed by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In an essay titled Specimina calculi rationalis, Leibniz develops a theory of propositional terms that allows him to derive the rule of reductio ad absurdum in a purely categor- ical calculus in which every proposition is of the form AisB. We reconstruct Leibniz’s categorical calculus and show that it is strong enough to establish not only the rule of reductio ad absurdum,but all the laws of classical propositional logic. Moreover, we show that the propositional logic generated by the nonmonotonic variant of Leibniz’s categorical calculus is a natural system of relevance logic ¬ known as RMI→ . From its beginnings in antiquity up until the late 19th century, the study of formal logic was shaped by two distinct approaches to the subject. The first approach was primarily concerned with simple propositions expressing predicative relations between terms. -

Logic: a Brief Introduction Ronald L

Logic: A Brief Introduction Ronald L. Hall, Stetson University Chapter 1 - Basic Training 1.1 Introduction In this logic course, we are going to be relying on some “mental muscles” that may need some toning up. But don‟t worry, we recognize that it may take some time to get these muscles strengthened; so we are going to take it slow before we get up and start running. Are you ready? Well, let‟s begin our basic training with some preliminary conceptual stretching. Certainly all of us recognize that activities like riding a bicycle, balancing a checkbook, or playing chess are acquired skills. Further, we know that in order to acquire these skills, training and study are important, but practice is essential. It is also commonplace to acknowledge that these acquired skills can be exercised at various levels of mastery. Those who have studied the piano and who have practiced diligently certainly are able to play better than those of us who have not. The plain fact is that some people play the piano better than others. And the same is true of riding a bicycle, playing chess, and so forth. Now let‟s stretch this agreement about such skills a little further. Consider the activity of thinking. Obviously, we all think, but it is seldom that we think about thinking. So let's try to stretch our thinking to include thinking about thinking. As we do, and if this does not cause too much of a cramp, we will see that thinking is indeed an activity that has much in common with other acquired skills. -

Aristotle on Predication

DOI: 10.1111/ejop.12054 Aristotle on Predication Phil Corkum Abstract: A predicate logic typically has a heterogeneous semantic theory. Sub- jects and predicates have distinct semantic roles: subjects refer; predicates char- acterize. A sentence expresses a truth if the object to which the subject refers is correctly characterized by the predicate. Traditional term logic, by contrast, has a homogeneous theory: both subjects and predicates refer; and a sentence is true if the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. In this paper, I will examine evidence for ascribing to Aristotle the view that subjects and predicates refer. If this is correct, then it seems that Aristotle, like the traditional term logician, problematically conflates predication and identity claims. I will argue that we can ascribe to Aristotle the view that both subjects and predicates refer, while holding that he would deny that a sentence is true just in case the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. In particular, I will argue that Aristotle’s core semantic notion is not identity but the weaker relation of consti- tution. For example, the predication ‘All men are mortal’ expresses a true thought, in Aristotle’s view, just in case the mereological sum of humans is a part of the mereological sum of mortals. A predicate logic typically has a heterogeneous semantic theory. Subjects and predicates have distinct semantic roles: subjects refer; predicates characterize. A sentence expresses a truth if the object to which the subject refers is correctly characterized by the predicate. Traditional term logic, by contrast, has a homo- geneous theory: both subjects and predicates refer; and a sentence is true if the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. -

The History of Logic

c Peter King & Stewart Shapiro, The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (OUP 1995), 496–500. THE HISTORY OF LOGIC Aristotle was the first thinker to devise a logical system. He drew upon the emphasis on universal definition found in Socrates, the use of reductio ad absurdum in Zeno of Elea, claims about propositional structure and nega- tion in Parmenides and Plato, and the body of argumentative techniques found in legal reasoning and geometrical proof. Yet the theory presented in Aristotle’s five treatises known as the Organon—the Categories, the De interpretatione, the Prior Analytics, the Posterior Analytics, and the Sophistical Refutations—goes far beyond any of these. Aristotle holds that a proposition is a complex involving two terms, a subject and a predicate, each of which is represented grammatically with a noun. The logical form of a proposition is determined by its quantity (uni- versal or particular) and by its quality (affirmative or negative). Aristotle investigates the relation between two propositions containing the same terms in his theories of opposition and conversion. The former describes relations of contradictoriness and contrariety, the latter equipollences and entailments. The analysis of logical form, opposition, and conversion are combined in syllogistic, Aristotle’s greatest invention in logic. A syllogism consists of three propositions. The first two, the premisses, share exactly one term, and they logically entail the third proposition, the conclusion, which contains the two non-shared terms of the premisses. The term common to the two premisses may occur as subject in one and predicate in the other (called the ‘first figure’), predicate in both (‘second figure’), or subject in both (‘third figure’). -

Review of Philosophical Logic: an Introduction to Advanced Topics*

Teaching Philosophy 36 (4):420-423 (2013). Review of Philosophical Logic: An Introduction to Advanced Topics* CHAD CARMICHAEL Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis This book serves as a concise introduction to some main topics in modern formal logic for undergraduates who already have some familiarity with formal languages. There are chapters on sentential and quantificational logic, modal logic, elementary set theory, a brief introduction to the incompleteness theorem, and a modern development of traditional Aristotelian Logic: the “term logic” of Sommers (1982) and Englebretsen (1996). Most of the book provides compact introductions to the syntax and semantics of various familiar formal systems. Here and there, the authors briefly indicate how intuitionist logic diverges from the classical treatments that are more fully explored. The book is appropriate for an undergraduate-level second course in logic that will approach the topic from a philosophical (rather than primarily mathematical) perspective. Philosophical topics (sometimes very briefly) touched upon in the book include: intuitionist logic, substitutional quantification, the nature of logical consequence, deontic logic, the incompleteness theorem, and the interaction of quantification and modality. The book provides an effective jumping-off point for several of these topics. In particular, the presentation of the intuitive idea of the * George Englebretsen and Charles Sayward, Philosophical Logic: An Introduction to Advanced Topics (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2013), 208 pages. 1 incompleteness theorem (chapter 7) is the right level of rigor for an undergraduate philosophy student, as it provides the basic idea of the proof without getting bogged down in technical details that would not have much philosophical interest. -

First-Order Logic

Lecture 14: First-Order Logic 1 Need For More Than Propositional Logic In normal speaking we could use logic to say something like: If all humans are mortal (α) and all Greeks are human (β) then all Greeks are mortal (γ). So if we have α = (H → M) and β = (G → H) and γ = (G → M) (where H, M, G are propositions) then we could say that ((α ∧ β) → γ) is valid. That is called a Syllogism. This is good because it allows us to focus on a true or false statement about one person. This kind of logic (propositional logic) was adopted by Boole (Boolean Logic) and was the focus of our lectures so far. But what about using “some” instead of “all” in β in the statements above? Would the statement still hold? (After all, Zeus had many children that were half gods and Greeks, so they may not necessarily be mortal.) We would then need to say that “Some Greeks are human” implies “Some Greeks are mortal”. Unfortunately, there is really no way to express this in propositional logic. This points out that we really have been abstracting out the concept of all in propositional logic. It has been assumed in the propositions. If we want to now talk about some, we must make this concept explicit. Also, we should be able to reason that if Socrates is Greek then Socrates is mortal. Also, we should be able to reason that Plato’s teacher, who is Greek, is mortal. First-Order Logic allows us to do this by writing formulas like the following. -

Accuracy Vs. Validity, Consistency Vs. Reliability, and Fairness Vs

Accuracy vs. Validity, Consistency vs. Reliability, and Fairness vs. Absence of Bias: A Call for Quality Accuracy vs. Validity, Consistency vs. Reliability, and Fairness vs. Absence of Bias: A Call for Quality Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education (AACTE) New Orleans, LA. February 2008 W. Steve Lang, Ph.D. Professor, Educational Measurement and Research University of South Florida St. Petersburg Email: [email protected] Judy R. Wilkerson, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Research and Assessment Florida Gulf Coast University email: [email protected] Abstract The National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE, 2002) requires teacher education units to develop assessment systems and evaluate both the success of candidates and unit operations. Because of a stated, but misguided, fear of statistics, NCATE fails to use accepted terminology to assure the quality of institutional evaluative decisions with regard to the relevant standard (#2). Instead of “validity” and ”reliability,” NCATE substitutes “accuracy” and “consistency.” NCATE uses the accepted terms of “fairness” and “avoidance of bias” but confuses them with each other and with validity and reliability. It is not surprising, therefore, that this Standard is the most problematic standard in accreditation decisions. This paper seeks to clarify the terms, using scholarly work and measurement standards as a basis for differentiating and explaining the terms. The paper also provides examples to demonstrate how units can seek evidence of validity, reliability, and fairness with either statistical or non-statistical methodologies, disproving the NCATE assertion that statistical methods provide the only sources of evidence. The lack of adherence to professional assessment standards and the knowledge base of the educational profession in both the rubric and web-based resource materials for this standard are discussed.