Propositional Logic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and Pragmatics Christopher Gauker Semantics deals with the literal meaning of sentences. Pragmatics deals with what speakers mean by their utterances of sentences over and above what those sentences literally mean. However, it is not always clear where to draw the line. Natural languages contain many expressions that may be thought of both as contributing to literal meaning and as devices by which speakers signal what they mean. After characterizing the aims of semantics and pragmatics, this chapter will set out the issues concerning such devices and will propose a way of dividing the labor between semantics and pragmatics. Disagreements about the purview of semantics and pragmatics often concern expressions of which we may say that their interpretation somehow depends on the context in which they are used. Thus: • The interpretation of a sentence containing a demonstrative, as in “This is nice”, depends on a contextually-determined reference of the demonstrative. • The interpretation of a quantified sentence, such as “Everyone is present”, depends on a contextually-determined domain of discourse. • The interpretation of a sentence containing a gradable adjective, as in “Dumbo is small”, depends on a contextually-determined standard (Kennedy 2007). • The interpretation of a sentence containing an incomplete predicate, as in “Tipper is ready”, may depend on a contextually-determined completion. Semantics and Pragmatics 8/4/10 Page 2 • The interpretation of a sentence containing a discourse particle such as “too”, as in “Dennis is having dinner in London tonight too”, may depend on a contextually determined set of background propositions (Gauker 2008a). • The interpretation of a sentence employing metonymy, such as “The ham sandwich wants his check”, depends on a contextually-determined relation of reference-shifting. -

Reference and Sense

REFERENCE AND SENSE y two distinct ways of talking about the meaning of words y tlkitalking of SENSE=deali ng with relationshippggs inside language y talking of REFERENCE=dealing with reltilations hips bbtetween l. and the world y by means of reference a speaker indicates which things (including persons) are being talked about ege.g. My son is in the beech tree. II identifies persons identifies things y REFERENCE-relationship between the Enggplish expression ‘this p pgage’ and the thing you can hold between your finger and thumb (part of the world) y your left ear is the REFERENT of the phrase ‘your left ear’ while REFERENCE is the relationship between parts of a l. and things outside the l. y The same expression can be used to refer to different things- there are as many potential referents for the phrase ‘your left ear’ as there are pppeople in the world with left ears Many expressions can have VARIABLE REFERENCE y There are cases of expressions which in normal everyday conversation never refer to different things, i.e. which in most everyday situations that one can envisage have CONSTANT REFERENCE. y However, there is very little constancy of reference in l. Almost all of the fixing of reference comes from the context in which expressions are used. y Two different expressions can have the same referent class ica l example: ‘the MiMorning St’Star’ and ‘the Evening Star’ to refer to the planet Venus y SENSE of an expression is its place in a system of semantic relati onshi ps wit h other expressions in the l. -

Pragmatics Is a Systematic Way of Explaining Language Use in Context

Pragmatics is a systematic way of explaining language use in context. It seeks to explain aspects of meaning which cannot be found in the plain sense of words or structures, as explained by semantics. As a field of language study, pragmatics is fairly new. Its origins lie in philosophy of language and the American philosophical school of pragmatism. As a discipline within language science, its roots lie in the work of (Herbert) Paul Grice on conversational implicature and the cooperative principle, and on the work of Stephen Levinson, Penelope Brown and Geoff Leech on politeness. We can illustrate how pragmatics works by an example from association football (and other field sports). It sometimes happens that a team-mate will shout at me: “Man on!” Semantic analysis can only go so far with this phrase. For example, it can elicit different lexical meanings of the noun “man” (mankind or the human race, an individual person, a male person specifically) and the preposition “on” (on top of, above, or other relationships as in “on fire”, “on heat”, “on duty”, “on the fiddle” or “on the telly”). And it can also explain structural meaning, and account for the way this phrase works in longer sequences such as the “first man on the moon”, “a man on the run” or “the man on top of the Clapham omnibus”. We use language all the time to make things happen. We ask someone to pass the salt or marry us - not, usually at the same time. We order a pizza or make a dental appointment. Speech acts include asking for a glass of beer, promising to drink the beer, threatening to drink more beer, ordering someone else to drink some beer, and so on. -

CAS LX 522 Syntax I

It is likely… CAS LX 522 IP This satisfies the EPP in Syntax I both clauses. The main DPj I′ clause has Mary in SpecIP. Mary The embedded clause has Vi+I VP is the trace in SpecIP. V AP Week 14b. PRO and control ti This specific instance of A- A IP movement, where we move a likely subject from an embedded DP I′ clause to a higher clause is tj generally called subject raising. I VP to leave Reluctance to leave Reluctance to leave Now, consider: Reluctant has two θ-roles to assign. Mary is reluctant to leave. One to the one feeling the reluctance (Experiencer) One to the proposition about which the reluctance holds (Proposition) This looks very similar to Mary is likely to leave. Can we draw the same kind of tree for it? Leave has one θ-role to assign. To the one doing the leaving (Agent). How many θ-roles does reluctant assign? In Mary is reluctant to leave, what θ-role does Mary get? IP Reluctance to leave Reluctance… DPi I′ Mary Vj+I VP In Mary is reluctant to leave, is V AP Mary is doing the leaving, gets Agent t Mary is reluctant to leave. j t from leave. i A′ Reluctant assigns its θ- Mary is showing the reluctance, gets θ roles within AP as A θ IP Experiencer from reluctant. required, Mary moves reluctant up to SpecIP in the main I′ clause by Spellout. ? And we have a problem: I vP But what gets the θ-role to Mary appears to be getting two θ-roles, from leave, and what v′ in violation of the θ-criterion. -

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics YEUNG, \y,ang -C-hun ...:' . '",~ ... ~ .. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy In Philosophy The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2010 Abstract of thesis entitled: Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics Submitted by YEUNG, Wang Chun for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in July 2009 This ,thesis investigates problems surrounding the lively debate about how Kripke's examples of necessary a posteriori truths and contingent a priori truths should be explained. Two-dimensionalism is a recent development that offers a non-reductive analysis of such truths. The semantic interpretation of two-dimensionalism, proposed by Jackson and Chalmers, has certain 'descriptive' elements, which can be articulated in terms of the following three claims: (a) names and natural kind terms are reference-fixed by some associated properties, (b) these properties are known a priori by every competent speaker, and (c) these properties reflect the cognitive significance of sentences containing such terms. In this thesis, I argue against two arguments directed at such 'descriptive' elements, namely, The Argument from Ignorance and Error ('AlE'), and The Argument from Variability ('AV'). I thereby suggest that reference-fixing properties belong to the semantics of names and natural kind terms, and not to their metasemantics. Chapter 1 is a survey of some central notions related to the debate between descriptivism and direct reference theory, e.g. sense, reference, and rigidity. Chapter 2 outlines the two-dimensional approach and introduces the va~ieties of interpretations 11 of the two-dimensional framework. -

The Metamathematics of Putnam's Model-Theoretic Arguments

The Metamathematics of Putnam's Model-Theoretic Arguments Tim Button Abstract. Putnam famously attempted to use model theory to draw metaphysical conclusions. His Skolemisation argument sought to show metaphysical realists that their favourite theories have countable models. His permutation argument sought to show that they have permuted mod- els. His constructivisation argument sought to show that any empirical evidence is compatible with the Axiom of Constructibility. Here, I exam- ine the metamathematics of all three model-theoretic arguments, and I argue against Bays (2001, 2007) that Putnam is largely immune to meta- mathematical challenges. Copyright notice. This paper is due to appear in Erkenntnis. This is a pre-print, and may be subject to minor changes. The authoritative version should be obtained from Erkenntnis, once it has been published. Hilary Putnam famously attempted to use model theory to draw metaphys- ical conclusions. Specifically, he attacked metaphysical realism, a position characterised by the following credo: [T]he world consists of a fixed totality of mind-independent objects. (Putnam 1981, p. 49; cf. 1978, p. 125). Truth involves some sort of correspondence relation between words or thought-signs and external things and sets of things. (1981, p. 49; cf. 1989, p. 214) [W]hat is epistemically most justifiable to believe may nonetheless be false. (1980, p. 473; cf. 1978, p. 125) To sum up these claims, Putnam characterised metaphysical realism as an \externalist perspective" whose \favorite point of view is a God's Eye point of view" (1981, p. 49). Putnam sought to show that this externalist perspective is deeply untenable. To this end, he treated correspondence in terms of model-theoretic satisfaction. -

Verifying the Unification Algorithm In

Verifying the Uni¯cation Algorithm in LCF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory Corn Exchange Street Cambridge CB2 3QG England August 1984 Abstract. Manna and Waldinger's theory of substitutions and uni¯ca- tion has been veri¯ed using the Cambridge LCF theorem prover. A proof of the monotonicity of substitution is presented in detail, as an exam- ple of interaction with LCF. Translating the theory into LCF's domain- theoretic logic is largely straightforward. Well-founded induction on a complex ordering is translated into nested structural inductions. Cor- rectness of uni¯cation is expressed using predicates for such properties as idempotence and most-generality. The veri¯cation is presented as a series of lemmas. The LCF proofs are compared with the original ones, and with other approaches. It appears di±cult to ¯nd a logic that is both simple and exible, especially for proving termination. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of uni¯cation 2 3 Overview of LCF 4 3.1 The logic PPLAMBDA :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 3.2 The meta-language ML :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 3.3 Goal-directed proof :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 3.4 Recursive data structures ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 4 Di®erences between the formal and informal theories 7 4.1 Logical framework :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.2 Data structure for expressions :::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.3 Sets and substitutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4.4 The induction principle :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 5 Constructing theories in LCF 10 5.1 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Syntax and Semantics of Propositional Logic

INTRODUCTIONTOLOGIC Lecture 2 Syntax and Semantics of Propositional Logic. Dr. James Studd Logic is the beginning of wisdom. Thomas Aquinas Outline 1 Syntax vs Semantics. 2 Syntax of L1. 3 Semantics of L1. 4 Truth-table methods. Examples of syntactic claims ‘Bertrand Russell’ is a proper noun. ‘likes logic’ is a verb phrase. ‘Bertrand Russell likes logic’ is a sentence. Combining a proper noun and a verb phrase in this way makes a sentence. Syntax vs. Semantics Syntax Syntax is all about expressions: words and sentences. ‘Bertrand Russell’ is a proper noun. ‘likes logic’ is a verb phrase. ‘Bertrand Russell likes logic’ is a sentence. Combining a proper noun and a verb phrase in this way makes a sentence. Syntax vs. Semantics Syntax Syntax is all about expressions: words and sentences. Examples of syntactic claims ‘likes logic’ is a verb phrase. ‘Bertrand Russell likes logic’ is a sentence. Combining a proper noun and a verb phrase in this way makes a sentence. Syntax vs. Semantics Syntax Syntax is all about expressions: words and sentences. Examples of syntactic claims ‘Bertrand Russell’ is a proper noun. ‘Bertrand Russell likes logic’ is a sentence. Combining a proper noun and a verb phrase in this way makes a sentence. Syntax vs. Semantics Syntax Syntax is all about expressions: words and sentences. Examples of syntactic claims ‘Bertrand Russell’ is a proper noun. ‘likes logic’ is a verb phrase. Combining a proper noun and a verb phrase in this way makes a sentence. Syntax vs. Semantics Syntax Syntax is all about expressions: words and sentences. Examples of syntactic claims ‘Bertrand Russell’ is a proper noun. -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

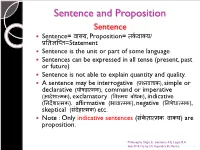

Logic- Sentence and Propositions

Sentence and Proposition Sentence Sentence= वा啍य, Proposition= त셍कवा啍य/ प्रततऻप्तत=Statement Sentence is the unit or part of some language. Sentences can be expressed in all tense (present, past or future) Sentence is not able to explain quantity and quality. A sentence may be interrogative (प्रश्नवाच셍), simple or declarative (घोषड़ा配म셍), command or imperative (आदेशा配म셍), exclamatory (ववमयतबोध셍), indicative (तनदेशा配म셍), affirmative (भावा配म셍), negative (तनषेधा配म셍), skeptical (संदेहा配म셍) etc. Note : Only indicative sentences (सं셍ेता配म셍तवा啍य) are proposition. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 1 All kind of sentences are not proposition, only those sentences are called proposition while they will determine or evaluate in terms of truthfulness or falsity. Sentences are governed by its own grammar. (for exp- sentence of hindi language govern by hindi grammar) Sentences are correct or incorrect / pure or impure. Sentences are may be either true or false. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 2 Proposition Proposition are regarded as the material of our reasoning and we also say that proposition and statements are regarded as same. Proposition is the unit of logic. Proposition always comes in present tense. (sentences - all tenses) Proposition can explain quantity and quality. (sentences- cannot) Meaning of sentence is called proposition. Sometime more then one sentences can expressed only one proposition. Example : 1. ऩानीतबरसतरहातहैत.(Hindi) 2. ऩावुष तऩड़तोत (Sanskrit) 3. It is raining (English) All above sentences have only one meaning or one proposition. -

Data Types & Arithmetic Expressions

Data Types & Arithmetic Expressions 1. Objective .............................................................. 2 2. Data Types ........................................................... 2 3. Integers ................................................................ 3 4. Real numbers ....................................................... 3 5. Characters and strings .......................................... 5 6. Basic Data Types Sizes: In Class ......................... 7 7. Constant Variables ............................................... 9 8. Questions/Practice ............................................. 11 9. Input Statement .................................................. 12 10. Arithmetic Expressions .................................... 16 11. Questions/Practice ........................................... 21 12. Shorthand operators ......................................... 22 13. Questions/Practice ........................................... 26 14. Type conversions ............................................. 28 Abdelghani Bellaachia, CSCI 1121 Page: 1 1. Objective To be able to list, describe, and use the C basic data types. To be able to create and use variables and constants. To be able to use simple input and output statements. Learn about type conversion. 2. Data Types A type defines by the following: o A set of values o A set of operations C offers three basic data types: o Integers defined with the keyword int o Characters defined with the keyword char o Real or floating point numbers defined with the keywords