Algebraic Structuralism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Formalization of Logic in Diagonal-Free Cylindric Algebras Andrew John Ylvisaker Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 A formalization of logic in diagonal-free cylindric algebras Andrew John Ylvisaker Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Ylvisaker, Andrew John, "A formalization of logic in diagonal-free cylindric algebras" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12536. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12536 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A formalization of logic in diagonal-free cylindric algebras by Andrew John Ylvisaker A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Mathematics Program of Study Committee: Roger D. Maddux, Major Professor Maria Axenovich Cliff Bergman Bill Robinson Paul Sacks Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright c Andrew John Ylvisaker, 2012. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES . iii LIST OF FIGURES . iv CHAPTER 1. BACKGROUND MATERIAL . 1 1.1 Introduction . .1 1.2 First-order logic . .4 1.3 General algebra and Boolean algebras with operators . .6 1.4 Relation algebras . 11 1.5 Cylindric algebras . 17 CHAPTER 2. RELATION ALGEBRAIC REDUCTS . 21 2.1 Definitions . 21 2.2 Preliminary lemmas . 27 + 2.3 Q RA reducts in Df3 ..................................... -

Weak Representation Theory in the Calculus of Relations Jeremy F

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2006 Weak representation theory in the calculus of relations Jeremy F. Alm Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Alm, Jeremy F., "Weak representation theory in the calculus of relations " (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1795. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1795 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Weak representation theory in the calculus of relations by Jeremy F. Aim A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Mathematics Program of Study Committee: Roger Maddux, Major Professor Maria Axenovich Paul Sacks Jonathan Smith William Robinson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright © Jeremy F. Aim, 2006. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3217250 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Verifying the Unification Algorithm In

Verifying the Uni¯cation Algorithm in LCF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory Corn Exchange Street Cambridge CB2 3QG England August 1984 Abstract. Manna and Waldinger's theory of substitutions and uni¯ca- tion has been veri¯ed using the Cambridge LCF theorem prover. A proof of the monotonicity of substitution is presented in detail, as an exam- ple of interaction with LCF. Translating the theory into LCF's domain- theoretic logic is largely straightforward. Well-founded induction on a complex ordering is translated into nested structural inductions. Cor- rectness of uni¯cation is expressed using predicates for such properties as idempotence and most-generality. The veri¯cation is presented as a series of lemmas. The LCF proofs are compared with the original ones, and with other approaches. It appears di±cult to ¯nd a logic that is both simple and exible, especially for proving termination. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of uni¯cation 2 3 Overview of LCF 4 3.1 The logic PPLAMBDA :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 3.2 The meta-language ML :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 3.3 Goal-directed proof :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 3.4 Recursive data structures ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 4 Di®erences between the formal and informal theories 7 4.1 Logical framework :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.2 Data structure for expressions :::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.3 Sets and substitutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4.4 The induction principle :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 5 Constructing theories in LCF 10 5.1 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

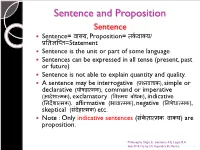

Logic- Sentence and Propositions

Sentence and Proposition Sentence Sentence= वा啍य, Proposition= त셍कवा啍य/ प्रततऻप्तत=Statement Sentence is the unit or part of some language. Sentences can be expressed in all tense (present, past or future) Sentence is not able to explain quantity and quality. A sentence may be interrogative (प्रश्नवाच셍), simple or declarative (घोषड़ा配म셍), command or imperative (आदेशा配म셍), exclamatory (ववमयतबोध셍), indicative (तनदेशा配म셍), affirmative (भावा配म셍), negative (तनषेधा配म셍), skeptical (संदेहा配म셍) etc. Note : Only indicative sentences (सं셍ेता配म셍तवा啍य) are proposition. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 1 All kind of sentences are not proposition, only those sentences are called proposition while they will determine or evaluate in terms of truthfulness or falsity. Sentences are governed by its own grammar. (for exp- sentence of hindi language govern by hindi grammar) Sentences are correct or incorrect / pure or impure. Sentences are may be either true or false. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 2 Proposition Proposition are regarded as the material of our reasoning and we also say that proposition and statements are regarded as same. Proposition is the unit of logic. Proposition always comes in present tense. (sentences - all tenses) Proposition can explain quantity and quality. (sentences- cannot) Meaning of sentence is called proposition. Sometime more then one sentences can expressed only one proposition. Example : 1. ऩानीतबरसतरहातहैत.(Hindi) 2. ऩावुष तऩड़तोत (Sanskrit) 3. It is raining (English) All above sentences have only one meaning or one proposition. -

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis Julian Hartman September 4, 2010 Abstract This paper is intended as an exploration of nonstandard analysis, and the rigorous use of infinitesimals and infinite elements to explore properties of the real numbers. I first define and explore first order logic, and model theory. Then, I prove the compact- ness theorem, and use this to form a nonstandard structure of the real numbers. Using this nonstandard structure, it it easy to to various proofs without the use of limits that would otherwise require their use. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 An Introduction to First Order Logic 2 2.1 Propositional Logic . 2 2.2 Logical Symbols . 2 2.3 Predicates, Constants and Functions . 2 2.4 Well-Formed Formulas . 3 3 Models 3 3.1 Structure . 3 3.2 Truth . 4 3.2.1 Satisfaction . 5 4 The Compactness Theorem 6 4.1 Soundness and Completeness . 6 5 Nonstandard Analysis 7 5.1 Making a Nonstandard Structure . 7 5.2 Applications of a Nonstandard Structure . 9 6 Sources 10 1 1 Introduction The founders of modern calculus had a less than perfect understanding of the nuts and bolts of what made it work. Both Newton and Leibniz used the notion of infinitesimal, without a rigorous understanding of what they were. Infinitely small real numbers that were still not zero was a hard thing for mathematicians to accept, and with the rigorous development of limits by the likes of Cauchy and Weierstrass, the discussion of infinitesimals subsided. Now, using first order logic for nonstandard analysis, it is possible to create a model of the real numbers that has the same properties as the traditional conception of the real numbers, but also has rigorously defined infinite and infinitesimal elements. -

Unification: a Multidisciplinary Survey

Unification: A Multidisciplinary Survey KEVIN KNIGHT Computer Science Department, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-3890 The unification problem and several variants are presented. Various algorithms and data structures are discussed. Research on unification arising in several areas of computer science is surveyed, these areas include theorem proving, logic programming, and natural language processing. Sections of the paper include examples that highlight particular uses of unification and the special problems encountered. Other topics covered are resolution, higher order logic, the occur check, infinite terms, feature structures, equational theories, inheritance, parallel algorithms, generalization, lattices, and other applications of unification. The paper is intended for readers with a general computer science background-no specific knowledge of any of the above topics is assumed. Categories and Subject Descriptors: E.l [Data Structures]: Graphs; F.2.2 [Analysis of Algorithms and Problem Complexity]: Nonnumerical Algorithms and Problems- Computations on discrete structures, Pattern matching; Ll.3 [Algebraic Manipulation]: Languages and Systems; 1.2.3 [Artificial Intelligence]: Deduction and Theorem Proving; 1.2.7 [Artificial Intelligence]: Natural Language Processing General Terms: Algorithms Additional Key Words and Phrases: Artificial intelligence, computational complexity, equational theories, feature structures, generalization, higher order logic, inheritance, lattices, logic programming, natural language -

Coll041-Endmatter.Pdf

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/coll/041 AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY COLLOQUIUM PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 41 A FORMALIZATION OF SET THEORY WITHOUT VARIABLES BY ALFRED TARSKI and STEVEN GIVANT AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND 1985 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primar y 03B; Secondary 03B30 , 03C05, 03E30, 03G15. Library o f Congres s Cataloging-in-Publicatio n Dat a Tarski, Alfred . A formalization o f se t theor y withou t variables . (Colloquium publications , ISS N 0065-9258; v. 41) Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Se t theory. 2 . Logic , Symboli c an d mathematical . I . Givant, Steve n R . II. Title. III. Series: Colloquium publications (American Mathematical Society) ; v. 41. QA248.T37 198 7 511.3'2 2 86-2216 8 ISBN 0-8218-1041-3 (alk . paper ) Copyright © 198 7 b y th e America n Mathematica l Societ y Reprinted wit h correction s 198 8 All rights reserve d excep t thos e grante d t o th e Unite d State s Governmen t This boo k ma y no t b e reproduce d i n an y for m withou t th e permissio n o f th e publishe r The pape r use d i n thi s boo k i s acid-fre e an d fall s withi n th e guideline s established t o ensur e permanenc e an d durability . @ Contents Section interdependenc e diagram s vii Preface x i Chapter 1 . Th e Formalis m £ o f Predicate Logi c 1 1.1. Preliminarie s 1 1.2. -

An Application of First-Order Compactness in Canonicity Of

An application of first-order compactness in canonicity of relation algebras Ian Hodkinson∗ June 17, 2019 Abstract The classical compactness theorem is a central theorem in first-order model theory. It sometimes appears in other areas of logic, and in per- haps surprising ways. In this paper, we survey one such appearance in algebraic logic. We show how first-order compactness can be used to sim- plify slightly the proof of Hodkinson and Venema (2005) that the variety of representable relation algebras, although canonical, has no canonical axiomatisation, and indeed every first-order axiomatisation of it has in- finitely many non-canonical sentences. 1 Introduction The compactness theorem is a fundamental result in first-order model theory. It says that every first-order theory (set of first-order sentences) that is consistent, in the sense that every finite subset of it has a model, has a model as a whole. Equivalently, if T;U are first-order theories, T j= U (meaning that every model of T is a model of U), and U is finite, then there is a finite subset T0 ⊆ T with T0 j= U. Though not nowadays the most sophisticated technique in model theory, compactness is still very powerful and has a firm place in my affections | as I believe it does in Mara's, since she devoted an entire chapter of her Model Theory book to it [26, chapter 5]. See [26, theorem 5.24] for the theorem itself. This paper was intended to be a short and snappy survey of a couple of applications of compactness in algebraic logic. -

A Short Proof of Representability of Fork Algebras

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Theoretical Computer Science ELSEVIER Theoretical Computer Science 188 ( 1997) 2 1l-220 A short proof of representability of fork algebras V&or Gyuris * Received June 1995; revised September IY96 Communicated by G. Mirkowska Abstract In this paper a strong relationship is demonstrated between fork algebras and quasi-projective relation algebras. With the help of Tarski’s classical representation theorem for quasi-projective relation algebras, a short proof is given for the representation theorem of fork algebras. As a by-product, we will discuss the difference between relative and absolute representation theorems. Fork algebras, due to their cxprcssive power and applicability in computer science, have been intensively studied in the last four years. Their literature is alive and pro- ductive. See e.g. Baum et al. [33,34.3,6-lo] and Sain-Simon [27]. As described in the textbook [15] 2.7.46, in algebra, there are two kinds of rep- resentation theorems: absolute and relative representation. For fork algebras absolute representation was proved almost impossible in [ l&27,26]. ’ However, relative repre- sentation is still possible and is quite useful (see e.g. [2]). The distinction between the two kinds of representation is not absolutely neces- sary for understanding the main contribution of this paper; therefore we postpone the description of this distinction to Remark 1 1 at the end of the paper. Several papers concentrate on giving a proof or an outline of proof for relative representability of fork algebras (e.g. -

Abstract Relation-Algebraic Interfaces for Finite Relations Between Infinite

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector The Journal of Logic and Algebraic Programming 76 (2008) 60–89 www.elsevier.com/locate/jlap Relational semigroupoids: Abstract relation-algebraic interfaces for finite relations between infinite types Wolfram Kahl ∗ Department of Computing and Software, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1 Available online 13 February 2008 Abstract Finite maps or finite relations between infinite sets do not even form a category, since the necessary identities are not finite. We show relation-algebraic extensions of semigroupoids where the operations that would produce infinite results have been replaced with variants that preserve finiteness, but still satisfy useful algebraic laws. The resulting theories allow calculational reasoning in the relation-algebraic style with only minor sacrifices; our emphasis on generality even provides some concepts in theories where they had not been available before. The semigroupoid theories presented in this paper also can directly guide library interface design and thus be used for principled relation-algebraic programming; an example implementation in Haskell allows manipulating finite binary relations as data in a point-free relation-algebraic programming style that integrates naturally with the current Haskell collection types. This approach enables seamless integration of relation-algebraic formulations to provide elegant solutions of problems that, with different data organisation, are awkward to tackle. © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. AMS classification: 18B40; 18B10; 03G15; 04A05; 68R99 Keywords: Finite relations; Semigroupoids; Determinacy; Restricted residuals; Direct products; Functional programming; Haskell 1. Introduction The motivation for this paper arose from the desire to use well-defined algebraic interfaces for collection datatypes implementing sets, partial functions, and binary relations. -

Lindström Theorems for Fragments of First-Order Logic

Logical Methods in Computer Science Vol. 5 (3:3) 2009, pp. 1–27 Submitted Feb. 16, 2008 www.lmcs-online.org Published Aug. 3, 2009 LINDSTROM¨ THEOREMS FOR FRAGMENTS OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC ∗ JOHAN VAN BENTHEM a, BALDER TEN CATE b, AND JOUKO VA¨ AN¨ ANEN¨ c a,c ILLC, University of Amsterdam e-mail address: {johan,vaananen}@science.uva.nl b ISLA, University of Amsterdam e-mail address: [email protected] Abstract. Lindstr¨om theorems characterize logics in terms of model-theoretic conditions such as Compactness and the L¨owenheim-Skolem property. Most existing characterizations of this kind concern extensions of first-order logic. But on the other hand, many logics relevant to computer science are fragments or extensions of fragments of first-order logic, e.g., k-variable logics and various modal logics. Finding Lindstr¨om theorems for these languages can be on coding arguments that seem to require the full expressive power of first-order logic. In this paper, we provide Lindstr¨om theorems for several fragments of first-order logic, including the k-variable fragments for k > 2, Tarski’s relation algebra, graded modal logic, and the binary guarded fragment. We use two different proof techniques. One is a modification of the original Lindstr¨om proof. The other involves the modal concepts of bisimulation, tree unraveling, and finite depth. Our results also imply semantic preserva- tion theorems. 1. Introduction There are many ways to capture the expressive power of a logical language L. For instance, one can characterize L as being a model-theoretically well behaved fragment of a richer language L′ (a preservation theorem), or as being maximally expressive while satis- fying certain model-theoretic properties (a Lindstr¨om theorem). -

First-Order Logic

Lecture 14: First-Order Logic 1 Need For More Than Propositional Logic In normal speaking we could use logic to say something like: If all humans are mortal (α) and all Greeks are human (β) then all Greeks are mortal (γ). So if we have α = (H → M) and β = (G → H) and γ = (G → M) (where H, M, G are propositions) then we could say that ((α ∧ β) → γ) is valid. That is called a Syllogism. This is good because it allows us to focus on a true or false statement about one person. This kind of logic (propositional logic) was adopted by Boole (Boolean Logic) and was the focus of our lectures so far. But what about using “some” instead of “all” in β in the statements above? Would the statement still hold? (After all, Zeus had many children that were half gods and Greeks, so they may not necessarily be mortal.) We would then need to say that “Some Greeks are human” implies “Some Greeks are mortal”. Unfortunately, there is really no way to express this in propositional logic. This points out that we really have been abstracting out the concept of all in propositional logic. It has been assumed in the propositions. If we want to now talk about some, we must make this concept explicit. Also, we should be able to reason that if Socrates is Greek then Socrates is mortal. Also, we should be able to reason that Plato’s teacher, who is Greek, is mortal. First-Order Logic allows us to do this by writing formulas like the following.