World's Fairs and the Department Store 1800S to 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

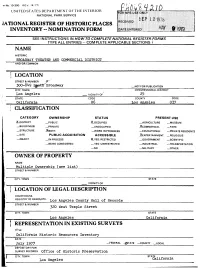

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Target Corporation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 4-7-2019 Strategic Audit: Target Corporation Andee Capell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Strategic Management Policy Commons Capell, Andee, "Strategic Audit: Target Corporation" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 192. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Strategic Audit: Target Corporation An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Andee Capell, BS Accounting College of Business April 7th, 2019 Faculty Mentor: Samuel Nelson, PhD, Management Abstract Target Corporation is a notable publicly traded discount retailer in the United States. In recent years they have gone through significant changes including a new CEO Brian Cornell and the closing of their Canadian stores. With change comes a new strategy, which includes growing stores in the United States. In order to be able to continue to grow Target should consider multiple strategic options. Using internal and external analysis, while examining Target’s profitability ratios recommendations were made to proceed with their growth both in profit and capacity. After recommendations are made implementation and contingency plans can be made. Key words: Strategy, Target, Ratio(s), Plan 1 Table of Contents Section Page(s) Background information …………………..…………………………………………….…..…...3 External Analysis ………………..……………………………………………………..............3-5 a. -

St John's University Undergraduate Student Managed Investment Fund Presents: Target Corporation Stock Analysis November 11, 20

St John’s University Undergraduate Student Managed Investment Fund Presents: Target Corporation Stock Analysis November 11, 2003 Recommendation: Purchase 300 shares of Target stock at market value Industry: Retail Analysts: Jennifer Tang – [email protected] Michael Vida – [email protected] Share Data: Fundamentals: Price - $39.15 P/E (2/03) – 21.63 Date – November 6, 2003 P/E (2/04E) – 21.96 Target Price – $44.58 P/E (2/05E) – 22.95 52 Week Price Range – $25.60 - $41.80 Book Value/Share – $11.03 Market Capitalization – $35.40 billion Price/Book Value – $3.60 Revenue 2002 – $43.917 billion Dividend Yield – 0.72% Projected EPS Growth – 15% Shares Outstanding – 910.9 million ROE 2002 – 17.51% Stock Chart: Executive Summary After analyzing Target Corp’s financials, industry and future outlook, we recommend the purchase of 300 shares of the company’s stock at market order. As a leading discount retailer, only behind Walmart, Target has made considerable growth in the industry over the past few years. Target offers an array of merchandise from women’s apparel, household products, toys and even food. One of the strengths of Target lies in its development of private brands, which helps create a strong image of the store in the customers’ minds. The company is able to further lower its costs through direct sourcing, buying merchandise at lower prices and strengthening its bargaining position with suppliers. While Target Corp hasn’t seen as much success with its other operations of Marshall Fields and Mervyn’s as it has with its namesake store, the company plans to invest resources into these two areas to turn around results. -

1 Draft Paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança

Draft paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança-Portugal University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Portugal [email protected] Power, cosmopolitanism and socio-spatial division in the commercial arena in Victorian and Edwardian London The developments of the English Revolution and of the British Empire expedited commerce and transformed the social and cultural status quo of Britain and the world. More specifically in London, the metropolis of the country, in the eighteenth century, there was already a sheer number of retail shops that would set forth an urban world of commerce and consumerism. Magnificent and wide-ranging shops served householders with commodities that mesmerized consumers, giving way to new traditions within the commercial and social fabric of London. Therefore, going shopping during the Victorian Age became mandatory in the middle and upper classes‟ social agendas. Harrods Department store opens in 1864, adding new elements to retailing by providing a sole space with a myriad of different commodities. In 1909, Gordon Selfridge opens Selfridges, transforming the concept of urban commerce by imposing a more cosmopolitan outlook in the commercial arena. Within this context, I intend to focus primarily on two of the largest department stores, Harrods and Selfridges, drawing attention to the way these two spaces were perceived when they first opened to the public and the effect they had in the city of London and in its people. I shall discuss how these department stores rendered space for social inclusion and exclusion, gender and race under the spell of the Victorian ethos, national conservatism and imperialism. -

Case No. DSP-15020-01 Capital Plaza Walmart Applicant

Case No. DSP-15020-01 Capital Plaza Walmart Applicant: Walmart Real Estate Business Trust FINAL DECISION ― DISAPPROVAL OF DETAILED SITE PLAN Detailed Site Plan 15020-01 (“DSP”), to construct a 35,287 square foot expansion to combine certain uses in the C-S-C Zone, is DISAPPOVED.1 FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW I. Procedural and Factual Background2 In September 2014, Walmart filed an application for a DSP with the Planning Department to expand its existing 144,227 square foot department store/retail “use”3 by 35,287 square 1 See the Land Use Article Section 25-210 (“LU”), Md. Ann. Code (2012 Ed. & Supp. 2015), the Prince George’s County Code, Subtitle 27, Section 27-290 (“PGCC”) (2015), and Cnty. Council of Prince George’s Cnty. v. Zimmer Dev. Co., 444 Md. 490; 120 A.3d 677 (2015) (The District Council is expressly authorized to review a final decision of the county planning board to approve or disapprove a detailed site plan and the District Council’s review results in a final decision). 2 The District Council may take judicial notice of any evidence contained in the record of any earlier phase of the approval process relating to all or a portion of the same property, including the approval of a preliminary plat of subdivision. See PGCC § 27-141. The District Council may also take administrative notice of facts of general knowledge, technical or scientific facts, laws, ordinances and regulations. It shall give effect to the rules of privileges recognized by law. The District Council may exclude incompetent, irrelevant, immaterial or unduly repetitious evidence. -

A Case Study: Tiffany &

F I R S T M E D I A Design Management Paper A CASE STUDY: TIFFANY & CO. PREPARED BY: TAN PEI LING DAPHNE TAN SHU MIN Introduction Tiffany & Co. (henceforth referred as “Tiffany”) is America’s premier purveyor of jewels and time- pieces, as well as luxury table, personal and household accessories. Founded in 1837 by Charles Lewis Tif- fany, Tiffany’s design philosophy has been based mainly on the central tenet that “good design is good busi- ness”1. All Tiffany’s designs are presented in the Tiffany Blue Box, recognized around the world as an icon of distinction and a symbol of the ultimate gift to celebrate life’s most joyous occasions. Today, the company’s 100 plus boutiques in 17 counties continue the company’s tradition of excellence2. This paper consists of several segments: (1) brief history of Tiffany; (2) organizational structure of the company; (3) marketing and product attributes; (4) target audience; (5) the unique selling proposition of its products; before concluding the paper. Brief History of Tiffany: 1837, Tiffany & Young is established Tiffany & Co. is a U.S. jewellery and silverware company founded by Charles Lewis Tiffany and Teddy Young in New York City in 1837 as a “stationery and fancy goods emporium.” The store initially sold a wide variety of stationery items, and operated as Tiffany, Young and Ellis in lower Manhattan. The name was shortened to Tiffany & Co in 1853 when Charles Tiffany took control, and the firm’s emphasis on jewel- lery was established. Tiffany & Co. has since opened stores in major cities all over the world. -

Automatic Merchandising of Grocery Products for Off-Premise Consumption

This dissertation has been 64—7067 microfilmed exactly as received VANDEMARK, Vern Alvin, 1917- AUTOMATIC MERCHANDISING OF GROCERY PRODUCTS FOR OFF-PREMISE CONSUMPTION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1963 Economics, commerce-business University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AUTOMATIC MERCHANDISING- OP GROCERY PRODUCTS FOR OFF-PREMISE CONSUMPTION dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor o f Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Vern Alvin Vandemark, B .S., M.A., M.S. ****** The Ohio State University 1963 Approved "by Adviser Department o f A gricultural Economics and Rural Sociology ACKK0WL3SDQMEHTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Automatic R etailers of America Educational Foundation, whose award o f a fellow ship made this study possible. The development and conclusions of the study, however, are wholly those of the author, who assumes all re sponsibility for the content of this dissertation. The author would also lik e to thank Professor Ralph W. Sherman for his counsel and guidance at every stage in the development of this study. Appreciation is expressed to Professors Elmer F. Baumer and George F. Henning who read the manuscript and offered valuable com ments and recommendations. The generous assistance and cooperation received from a great many individuals and organizations, without which this study would have been impossible, is gratefully acknowl edged. There is also need to mention the encouragement and moral support that I received from my wife, Joanne, and the continued interest and patience of my children, Susanne and John. Without the wholehearted support of my family, this study would have been most difficult, if not impossible. -

SUN BUILDING, 280 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Camnission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1439 SUN BUILDING, 280 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1845-46, 1850-51, 1852-53, 1872, 1884; architects Joseph Trench & Co., Trench & Snook, [Frederick] Schmidt, Edward D. Harris Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 153, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described building is situated. On June 14, 1983, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Sun Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 14}. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. The Camnission has received l etters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation, including a letter from the Camnissioner of the Department of General Services. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Sun Building, originally the A.T. Stewart Store, is one of the most influential buildings erected in New York City during the 19th century. Its appearance in 1846 (Fig.1} introduced a new architectural mode based on the palaces of the Italian Renaissance. Designed by the New York architects, Joseph Trench and John B. Snook, it was built by one of the century's greatest merchants, Alexander Turney Stewart. Within its marble walls, Stewart began the city's first department store, a type of commercial enterprise which was to have a great effect on the city's economic growth and which would change the way of merchandising in this country. -

Transformation

V. V. 03. 2019 23. Jahrgang 2019 | € 12 | ISSN 1614-7804 Seit 1996 das Verbandsmagazin des German Council of Shopping Centers e. V. (GCSC), dem bundesweit einzigen Interessenverband der Handelsimmobilienwirtschaft. German Council of Shopping Centers e. Impulse, Trends und Informationen für Handel, Städte, Immobilienwirtschaft und Omni channel-Marktplätze TRANSFORMATION 2019 INTERVIEW TRANSFORMATION INTERVIEW / 3 · »In Gelsenkirchen haben binnen »Piggly Wiggly« heißt »Wir wollen die Krise mit aller einer Dekade 10.000 Menschen wackelndes Schweinchen ... Macht aussitzen, statt sie zu einen neuen Job gefunden« Ein Deutscher und drei Amerikaner haben im beenden« Wirtschaftsförderer Dr. Christopher Schmitt über vergangenen Jahrhundert den Einzelhandel Dr. Stefan Kooths, Institut für Weltwirtschaft, Schalke 04 als Wegbereiter für eine boomende radikal verändert. Sie sind die Motoren der über mögliche Krisen in der Zukunft, die Gesundheitswirtschaft, Millionen-Investitionen Entwicklung von kleinen Läden hin zu expansive Geldpolitik der Europäischen · GERMAN COUNCIL MAGAZIN von BP und »Feierabendmärkte«, die den modernen Supermärkten mit Selbstbedie- Zentralbank, und warum Kassandra-Rufe GCM Einzelhandel stärken nungskassen und Internetshops aus der Wissenschaft selten erhört werden EmotionsCreating First Christmas by ROSENAU GmbH - The Specialist in Christmas Decorations T: +49 40 8664 8750 - [email protected] - www.firstchristmas.com VORWORT Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, wir haben die diesjährigen Inhalte und somit All das macht das Leben nicht einfacher. So antworten die Jungen, dass sie nicht wüssten, den Schwerpunkt des German Council Con- zumindest scheint in großen Teilen die öffentli- ob wir in 20 Jahren überhaupt noch Auto fah- gress unter die Überschrift TRANSFORMATION che Meinung zu sein. ren. gestellt. Auch in dieser Ausgabe wollen wir uns dem Thema auf unterschiedliche Weise wid- Der Mensch hat sich aber in seiner gesamten Veränderte Werte führen zu veränderten Be- men. -

Changing Patterns of Urban Retailing

ChangingPatterns of Urban Retailing: The 1920s JamesH. Madison Departmentof History,Indiana University During the 1920s fundamental changes occurred in business institutions responsible for retail distribution. Most signif- icantly, the large urban department store began a period of rela- tive decline and new forms of retailing emerged as strong compet- itors for sales volume. This paper describes these developments and attempts to show their relationship to the changing structure of American cities and to the changing strategies and structures of retail business institutions. It attempts also to show that changes in urban retailing commonly associated with post-World War II were well underway by the 1920s. First appearing in the third quarter of the 19th century, the department store occupied by 1900 the preeminent position in urban retailing, the consequence in part of the transformation of the city in the late 19th century. Rapid urban population growth and the spread of mass transit lines created a large number of consumers in a concentrated market area. Located at the conver- gence of transit lines and at the focal point of the newly con- centrated central business district, department stores drew cus- tomers from the entire city and increasingly from the surrounding countryside -- as many as 40,000 a day through Philadelphia's leading department store [18; 48; and 45, p. 467]. The compact and centralized spatial structure of late 19th century cities was a primary factor enabling the department store to achieve unprecedentedly high sales volume. That high volume resulted also from the strategy of selling under one roof goods of great variety, especially those appealing to a rapidly growing middle-class urban population. -

General Background

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 A Thesis in Geography by Wesley J Stroh © 2008 Wesley J Stroh Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Wesley J. Stroh was reviewed and approved* by the following: Deryck W. Holdsworth Professor of Geography Thesis Adviser Roger M. Downs Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ABSTRACT RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 Consolidation in the retail sector continues to restructure the department store, and the legacies of earlier forms of the department store laid the foundation for this consolidation. Using John Wanamaker’s and Strawbridge & Clothier, antecedents of Macy’s stores in Philadelphia, I undertake a case study of the development, through expansion and consolidation, which led to a homogenized department store retail market in the Philadelphia region. I employ archival materials, biographies and histories, and annual reports to document and characterize the development and restructuring Philadelphia’s department stores during three distinct phases: early expansions, the first consolidations into national corporations, and expansion through branch stores and into suburban shopping malls. In closing, I characterize the processes and structural legacies which department stores inherited by the latter half of the 20th century, as these legacies are foundational to national-scale retail homogenization. -

Dr. Marvin R. Bensman

Radio Pioneer: Victor H. Laughter Dr. Marvin R. Bensman We know rather little about the earliest history of wireless development other than stories about those particular pioneers whose efforts were influential or successful. It should not surprise those who study that history to discover that many individuals did not achieve success but contributed much. One fascinating story that has never been told is that of Mr. Victor H. Laughter. Victor H. Laughter was born January, 1888, in Byhalia, Mississippi. 1 At the age of 12, Laughter and his sister Belva boarded with Andersen W. Meely of Byhalia, Mississippi, while attending the Waverly Institute. 2 They may have been orphaned. It was during this time, in 1900, that Laughter built his first experimental wireless set. Later, Belva married a Mr. Joseph Thompson and moved to Memphis. 3 We have no direct record of Victor H. Laughter's further education in the field of wireless or electricity, but he most likely attended some college or institute between 1906 and 1909. In 1909, his book, Operator's Wireless Telegraph and Telephone Handbook, was published by Frederick J. Drake and Company. The book was written ". with the end in view of leading the student through the experimental stage, on up to the more complicated types of wireless telegraph and telephone instruments."4 The book was a well written and complete description of the wireless field up to that time, with a section on Dr. Lee deForest's audion which had only been patented that year. Laughter noted: "The Audion has proven very sensitive for use in wireless telephony, yet it is doubtful that it will ever come into wide use, owing to the difficulty in manufacture and short life."5 This was a true statement for that time.