2 FEBBRAIO 2015 Palazzo Dell'istruzione

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Spiritual Matter of Art Curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020

on the spiritual matter of art curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020 JOHN ARMLEDER | MATILDE CASSANI | FRANCESCO CLEMENTE | ENZO CUCCHI | ELISABETTA DI MAGGIO | JIMMIE DURHAM | HARIS EPAMINONDA | HASSAN KHAN | KIMSOOJA | ABDOULAYE KONATÉ | VICTOR MAN | SHIRIN NESHAT | YOKO ONO | MICHAL ROVNER | REMO SALVADORI | TOMÁS SARACENO | SEAN SCULLY | JEREMY SHAW | NAMSAL SIEDLECKI with loans from: Vatican Museums | National Roman Museum | National Etruscan Museum - Villa Giulia | Capitoline Museums dedicated to Lea Mattarella www.maxxi.art #spiritualealMAXXI Rome, 16 October 2019. What does it mean today to talk about spirituality? Where does spirituality fit into a world dominated by a digital and technological culture and an ultra-deterministic mentality? Is there still a spiritual dimension underpinning the demands of art? In order to reflect on these and other questions MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts, is bringing together a number of leading figures from the contemporary art scene in the major group show on the spiritual matter of art, strongly supported by the President of the Fondazione MAXXI Giovanna Melandri and curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (from 17 October 2019 to 8 March 2020). Main partner Enel, which for the period of the exhibition is supporting the initiative Enel Tuesdays with a special ticket price reduction every Tuesday. Sponsor Inwit. on the spiritual matter of art is a project that investigates the issue of the spiritual through the lens of contemporary art and, at the same time, that of the ancient history of Rome. In a layout offering diverse possible paths, the exhibition features the works of 19 artists, leading names on the international scene from very different backgrounds and cultures. -

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E

HSAR 252 - Roman Architecture with Professor Diana E. E. Kleiner Lecture 6 – Habitats at Herculaneum and Early Roman Interior Decoration 1. Title page with course logo. 2. Map of Italy in Roman times. Credit: Yale University. 3. Herculaneum, aerial view of ancient remains. Credit: Google Earth. 4. Herculaneum, view of ancient remains with modern apartment houses. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 5. Herculaneum, view of ancient remains. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. 6. Casa a Graticcio, Herculaneum, general view. Image Credit: Diana E. E. Kleiner. Wooden partition, Herculaneum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herculaneum_Casa_del_Tramezzo_di_Legno_-8.jpg (Accessed January 29, 2009). Bed, Herculaneum [online image]. Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Herculaneum_Casa_del_Tramezzo_di_Legno_Letto.jpg (Accessed January 29, 2009). 7. Skeletons, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 556. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Skeletons, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 562. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 8. Rings, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 560 (bottom). Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Bracelets, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 561. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. Skeleton of woman, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 560 top. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 9. Skeleton of pregnant woman with fetus, Herculaneum. Reproduced from National Geographic vol. 165, no. 5, May 1984, p. 564. Photograph by O. Louis Mazzatenta. 10. Crib with skeletal remains of an infant, Herculaneum. -

Best Sculpture in Rome"

"Best Sculpture in Rome" Créé par: Cityseeker 11 Emplacements marqués Wax Museum "History in Wax" Linked to the famed Madame Tussaud's in London, the Museo delle Cere recreates historical scenes such as Leonardo da Vinci painting the Mona Lisa surrounded by the Medici family and Machiavelli. Another scene shows Mussolini's last Cabinet meeting. There is of course a chamber of horrors with a garrotte, a gas chamber and an electric chair. The museum by _Pek_ was built to replicate similar buildings in London and Paris. It is a must visit if one is ever in the city in order to take home some unforgettable memories. +39 06 679 6482 Piazza dei Santi Apostoli 68/A, Rome Capitoline Museums "Le premier musée du monde" Les musées Capitoline sont dans deux palais qui se font face. Celui sur la gauche des marches de Michelange est le Nouveau Palais, qui abrite l'une des plus importantes collections de sculptures d'Europe. Il fut dessiné par Michelange et devint le premier musée public en 1734 sur l'ordre du pape Clément XII. L'autre palais, le Conservatori, abrite d'importantes peintures by Anthony Majanlahti comme St Jean Baptiste de Caravaggio et des oeuvres de titian, veronese, Rubens et Tintoretto. Une sculpture d'un énorme pied se trouve dans la cours, et faisait autrefois partie d'une statue de l'empereur Constantin. Une des ouvres fameuses est sans aucun doute la louve, une sculpture étrusque du 5ème siècle avant J-C à laquelle Romulus et Rémus furent ajoutés à la Renaissance. +39 06 0608 www.museicapitolini.org/s info.museicapitolini@comu Piazza Campidoglio, Rome ede/piazza_e_palazzi/pala ne.roma.it zzo_dei_conservatori#c Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica "Sculpturally Speaking" The Palazzo della Piccola Farnesina, built in 1523, houses the Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica, formed from a collection of pre-Roman art sculptures, Assyrian bas-reliefs, Attic vases, Egyptian hieroglyphics and exceptional Etruscan and Roman pieces. -

Great Libraries of Rome TOUR HIGHLIGHTS

The Sistine Hall of the Vatican Library / Anna & Michal OCTOBER 3–11, 2020 Great Libraries of Rome TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Tour the most beautiful libraries of Rome and see their rare manuscript collections. By special arrangement, enter the Vatican Museums before they open to the public. Gain behind-the-scenes- access to a private villa opened by the owners exclusively for Manuscript Society travelers. Enter the Vatican Library by special permission to see important manuscripts housed in the collection. HOTEL ACCOMMODATIONS Luxe Rose Garden Hotel in Rome Enjoy the gracious amenities and central location of the Luxe Rose Garden Hotel, situated within walking distance of the Villa Borghese, the Spanish Steps, and the Trevi Fountain. The superior 4-star hotel’s Roseto restaurant allows guests to enjoy a range of Italian specialties in an idyllic rose garden setting. With a gym, spa, and lovely small indoor pool, the Rose Garden meets guests’ every need to relax after a long day of sightseeing. (left) Parnassus and School of Athens (details), Room of the Segnatura, c. 1508-1520, Raphael, Vatican Museums (Oro1) CUSTOM ITINERARY This custom travel program has been created uniquely for The Manuscript Society. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2020 Departures Travelers will board independent flights to Rome Fiumicino Airport (FCO) from the United States. SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2020 Welcome to Rome Upon arrival at the Rome Fiumicino Airport (FCO), take private car transfers to the Luxe Rose Garden Hotel to check in. Gather this evening for a private visit to the French Academy in Rome, housed in the breathtaking surroundings of the Villa Medici complex. -

Imperial Image Prescribed Sources: Study Notes 2

Open University Department of Classical Studies Resources for A-Level Classical Civilisation Imperial Image Prescribed Sources: Study Notes 2 Prima Porta Statue Propertius Elegies 3.4 (War and Peace) Propertius Elegies 3.11 (Woman’s Power) Propertius Elegies 3.12 (Chaste and Faithful Galla) Propertius Elegies 4.6. (The Temple of Palatine Apollo) Ovid Metamorphoses 15.745-870 Suetonius Life of Augustus The Forum of Augustus Coin: Octavian/Restorer of laws and rights Coin: Augustus/Comet Coin: Augustus/Gaius and Lucius Caesar Imperial Image Augustus of Prima Porta (Statue) Context: Parthia: What?: Statue of Augustus. • Decoration includes a depiction of the return of When?: c. 20 BC. the Parthian standards. Where?: Found at Villa of Livia at Prima Porta. • Crassus lost these legionary standards to the Material: Marble (may have been a copy of a bronze statue Parthians in 53 BC. 40,000 Roman soldiers were set up elsewhere in Rome). killed. Height: 2.08 metres. • Tiberius negotiated the return of the standards in 20 BC. • The return of the standards was presented as Parthia submitting to Roman control, but Parthia remained an independent state. Stance/Posture: At the Feet: • Standing statue of a male. • Adjacent to the right leg is a cupid riding a • The figure appears young and athletic. dolphin. • Musculature is defined in the arms, legs and • This addition gave stability to the statue. breastplate. • The dolphin recalls Venus’ birth from the sea. • The pose and weight distribution echoes the • Venus was the mother of Aeneas, an ancestor of Doryphoros statue type, an embodiment of the Julian clan. -

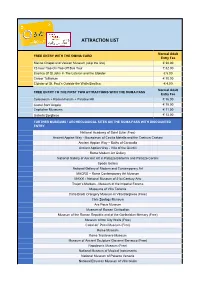

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

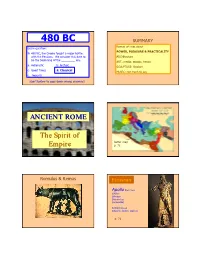

480 BC SUMMARY Roman Art Was About Exam Question: POWER, PLEASURE & PRACTICALITY in 480 BC, the Greeks Fought a Major Battle with the Persians

480 BC SUMMARY Roman art was about Exam question: POWER, PLEASURE & PRACTICALITY In 480 BC, the Greeks fought a major battle with the Persians. We consider this date to ARCHitecture be the beginning of the _________ era. ART: media: mosaic, fresco a. Hellenistic b. Archaic SCULPTURE: Realism c. Good Times d. Classical MUSIC: not much to say e. Imperial (don’t bother to copy down wrong answers!) map ANCIENT ROME The Spirit of better map Empire p. 72 Romulus & Remus Etruscan Apollo from Veii 500 b.c Life size Baked clay (terracotta) Archaic Greek influence (smile, stance) p. 71 But first some connections and 3 Roman Periods comparisons . Ancient Greek Hellenistic Age ends in • Roman Republic 509 - 27 BC 145 BC – why? • Early empire 27 BC - 180 AD PAX ROMANA ends with the reign of Marcus Aurelius • Late empire 180 - 395 AD ROMAN about 900 years CONQUEST Other cultures 3 timelines Ancient Egypt 3150 – 702 BC ROME – about 2500 years 900 years China Roman Republic Early & Late Imperial Rome Shang Dynasty starts 1523 BC; more-or-less continuous Chinese culture since then, Classical Greek Hellenistic about 3500 years Archaic Greek Qin Dynasty consolidates China, 221-206 BC, about 16 years HAN DYNASTY - CHINA Chin Zhou Qin 3 Kingdoms Han Dynasty 206 BC – 220 CE classical phase of Chinese civilization, 0 about 400 years Classical – some definitions Roman contributions 1. [culturally inclusive] Definitive (defining) and enduring • Literature 2. [narrow sense] art & architecture of Greek & Roman antiquity • Continuation of Greek models in art & philosophy 3. [another general sense] ‘art which aspires to emotional and physical • Architecture equilibrium, rationally rather than intuitively constructed’ Post & Lintel Post & Lintel drawbacks LINTEL construction P P O O LINTEL GREEK S S P P T T O O S S PARTHENON thick thick T T narrow Something new under the sun . -

“Empire Without End”: Augustan Rome and the Founding of the Principate Humanities and Religious Studies 196A

“Empire without End”: Augustan Rome and the Founding of the Principate Humanities and Religious Studies 196A A focused study of Roman cultural history at the time of the transition, orchestrated primarily by the emperor Augustus, from the republic to the principate (or empire). Emphasis will be on understanding Augustan values through attention to the literature, visual arts, architecture, and governmental, social, and economic policies that helped to establish the principate according to Augustus’ vision. Course time in Rome will be devoted primarily to visiting archaeological sites, monuments, and museum collections, and to ongoing discussion of their relationship to important literary works (to be studied prior to departure), and of the relevance of all these various manifestations of Augustan culture to the emperor’s program of reform. Expected Learning Outcomes Students will be able to: • Summarize the historical framework of the late republican and early imperial periods (i.e., 133 BCE to 68 CE) and explain key historical events for understanding Augustan culture • Define auctoritas as it applies to Augustus and the Augustan period, and cite examples drawn from various forms of literature and material culture • Identify traditional Roman values that Augustus emphasized, and explain how these values were manifested in Augustan culture • Describe a wide variety of literary works, archaeological sites, and architectural and artistic achievements from the Augustan period • Differentiate the main political and social components of the republican period from those of the early principate • Identify examples of Augustan influence on subsequent historical developments, as manifested in cultural features of Rome Course Requirements Required readings • Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture • Selected readings to be assigned by instructor (e.g. -

The Laurel Grove of the Caesars: Looking in and Looking Out*

The laurel grove of the Caesars: looking in and looking out* ALLAN KLYNNE Abstract The present paper represents an attempt to imagine the visual impact of the garden terrace in the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta. Excavations on the terrace have brought to light numerous planting pots and the remains of a double aisled portico. This evidence allows for a tentative reconstruction, which brings about considerations about the intentions behind the design of the garden sector of the villa and its date. It is argued that the sculpting of the hilltop should be understood as an intentional act to dominate the visual ideology of the landscape, where the outward display and the view had by others of the villa and its laurel grove was the prime concern. It is suggested that the complex might have served as a visual statement of the sacral dimension of the Augustan rule, alluding to the architecture of a sanctuary. In connection to this, other monuments, such as the tropaeum at Nikopolis, are brought in as analogies. Introduction difference in level (some 5–7 m) along the N side, has re- mained understudied over the years. In 1956 Heinz Käh- Whereas the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta is well known ler carried out a limited investigation of the terrace, with for its garden frescoes and the cuirassed statue of Au- the intention of finding the original spot of display for gustus found in 1863, the actual plan of the villa is still the statue of Augustus. From the weeds growing across incompletely understood. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR .... -

Best Museums in Rome"

"Best Museums in Rome" Créé par: Cityseeker 21 Emplacements marqués Complesso del Vittoriano "Warriors at Eternal Rest" Popular among locals as Il Milite Ignoto 'The Unknown Soldier', Complesso del Vittoriano is a museum that houses the bodies of various soldiers who fought in the World War I. After efforts of more than 20 years put into constructing this monument, it was finally completed in 1911. The architecture and exterior of the museum is of equal importance. The front by Paolo Costa Baldi facade of the museum is embellished with statues representing the various regions of Italy. The fountains of the two seas, greets visitors who enter through the gates. Do pay close attention to the inscriptions on various artifacts. +39 06 678 0664 www.ilvittoriano.com/ Via di San Pietro in Carcere, Rome Wax Museum "History in Wax" Linked to the famed Madame Tussaud's in London, the Museo delle Cere recreates historical scenes such as Leonardo da Vinci painting the Mona Lisa surrounded by the Medici family and Machiavelli. Another scene shows Mussolini's last Cabinet meeting. There is of course a chamber of horrors with a garrotte, a gas chamber and an electric chair. The museum by _Pek_ was built to replicate similar buildings in London and Paris. It is a must visit if one is ever in the city in order to take home some unforgettable memories. +39 06 679 6482 Piazza dei Santi Apostoli 68/A, Rome Capitoline Museums "Le premier musée du monde" Les musées Capitoline sont dans deux palais qui se font face. Celui sur la gauche des marches de Michelange est le Nouveau Palais, qui abrite l'une des plus importantes collections de sculptures d'Europe. -

St. Mary Major Termini Visitors Centre Vatican City

VISITORS CENTRE VATICAN CITY VIA LUDOVISI 8 VENETO VISITORS CENTRE 9 BARBERINI VISITORS CENTRE TERMINI STATION VISITORS CENTRE ST. PETER’S BASILICA TREVI 7 1 TERMINI FOUNTAIN VATICAN & ST ANGELO 6 17 12 ST. MARY MAJOR 10 2 11 1 7 15 13 16 PIAZZA FREE WALKING TOURS VENEZIA 5 2 Walk 1: In the heart of the Eternal City 6 14 2 Capitoline Hill 11 Piazza Farnese 5 13 Piazza Venezia 12 Piazza Navona 7 Largo Argentina 10 Pantheon 4 1 Campo de’ Fiori 17 Trevi Fountain 9 8 Walk 2: Colosseum and Ancient Forum 3 COLOSSEUM 2 Capitoline Hill 5 Forum 13 Piazza Venezia 4 Colosseum 3 15 Trajan’s Column 9 Palatine Hill 16 Trajan’s Markets CIRCO 4 MASSIMO Walk 3: From Ghetto to Colosseum 14 Teatro Marcello 3 Circus Maximus 6 Ghetto 9 Palatine Hill 8 Mouth of Truth 4 Colosseum MAP LEGEND STOPS AND ATTRACTIONS DATES AND TIMES PANORAMIC ROUTE / WEEKDAYS FREQUENCY PANORAMIC ROUTE / HOLIDAYS 1 TERMINI STATION DAILY First Dep: 8:30 AM | Last Complete Run: 6:45 PM | End of service: 8:30 PM 10/15 MINUTES LARGO DI VILLA PERETTI CORNER PIAZZA DEI CINQUECENTO I LOVE ROME Main Train Station, if you get o! here you can visit FIRST DEPARTURE POINTS the National Roman Museum , Piazza della Repubblica and Via Nazionale for relaxing shopping. TERMINI STATION 8:30 AM I LOVE ROME GUIDED TOURS AND ACTIVITIES 2 ST. MARY MAJOR First Dep: 8:40 AM | Last Complete Run: 5:10 PM | End of service: 6:55 PM LAST DEPARTURE PIAZZA ESQUILINO, 12 TERMINI STATION GENERAL INFORMATION Visit one of the most ancient Basilicas of Christianity and, very M T W T F S S close, the S.