The Somerset & Dorset Railwayанаalong the Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desk-Based Assessment Report’, Wessex Archaeology Unpublished Report Ref: 47394.1, Salisbury Margary, I D, 1955, Roman Roads in Britain: Vol

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S S O U T H W E S T Land at Moons Hill Quarry, Stoke St Michael, Somerset An archaeological desk-based assessment by Tim Dawson Site Code MHQ12/56 (ST 6550 4630, ST 6570 4540, ST 6611 4540 and ST 6657 4547) Land at Moons Hill Quarry, Stoke St Michael, Somerset Archaeological Desk-based Assessment for John Wainwright and Company Limited by Tim Dawson Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code MHQ 12/56 April 2014 Summary Site name: Land at Moons Hill Quarry, Stoke St Michael, Somerset Grid reference: ST 6550 4630, ST 6570 4540, ST 6611 4540 and ST 6657 4547 Site activity: An archaeological desk-based assessment Project manager: Andrew Weale Site supervisor: Tim Dawson Site code: MHQ 12/56 Area of site: c.40.28ha Summary of results: This report assesses the archaeological potential of four proposal sites for the development of a quarry tip. The northern and eastern sites, (Areas A, D and parts of C), have lower potential as there are very few sites of archaeological interest in their immediate neighbourhood. It is suggested that mitigation of the development on any archaeological deposits present could be suitably achieved by a recording action implemented by an appropriately worded condition to any consent gained. The south western area (Area B and part of C), however, have higher potential due to the projected line of a Roman road crossing their location and the presence nearby of a possible round barrow cemetery. -

Walk Westward Now Along This High Ridge and from This Vantage Point, You Can Often Gaze Down Upon Kestrels Who in Turn Are Scouring the Grass for Prey

This e-book has been laid out so that each walk starts on a left hand-page, to make print- ing the individual walks easier. When viewing on-screen, clicking on a walk below will take you to that walk in the book (pity it can’t take you straight to the start point of the walk itself!) As always, I’d be pleased to hear of any errors in the text or changes to the walks themselves. Happy walking! Walk Page Walks of up to 6 miles 1 East Bristol – Pucklechurch 3 2 North Bristol – The Tortworth Chestnut 5 3 North Bristol – Wetmoor Wood 7 4 West Bristol – Prior’s Wood 9 5 West Bristol – Abbots Leigh 11 6 The Mendips – Charterhouse 13 7 East Bristol – Willsbridge & The Dramway 16 8 Vale of Berkeley – Ham & Stone 19 Walks of 6–8 miles 9 South Bristol – Pensford & Stanton Drew 22 10 Vale of Gloucester – Deerhurst & The Severn Way 25 11 Glamorgan – Castell Coch 28 12 Clevedon – Tickenham Moor 31 13 The Mendips – Ebbor Gorge 33 14 Herefordshire – The Cat’s Back 36 15 The Wye Valley – St. Briavels 38 Walks of 8–10 miles 16 North Somerset – Kewstoke & Woodspring Priory 41 17 Chippenham – Maud Heath’s Causeway 44 18 The Cotswolds – Ozleworth Bottom 47 19 East Mendips – East Somerset Railway 50 20 Forest of Dean – The Essence of the Forest 54 21 The Cotswolds – Chedworth 57 22 The Cotswolds – Westonbirt & The Arboretum 60 23 Bath – The Kennet & Avon Canal 63 24 The Cotswolds – The Thames & Severn Canal 66 25 East Mendips – Mells & Nunney 69 26 Limpley Stoke Valley – Bath to Bradford-on-Avon 73 Middle Hope (walk 16) Walks of over 10 miles 27 Avebury – -

Whitchurch Village Council Response

Whitchurch Village Council Community Centre Office Bristol Road Whitchurch Bristol BS14 0PT [email protected] nd 2 March 2019 Dear Sir/Madam, WVC: Objection to WECA JLTP4 2019-2036 Consultation Please find enclosed an objection to the WECA Joint Local Transport Plan for 2019 – 2036 on behalf of Whitchurch Village Council (WVC). WVC has responsibility for the whole parish of Whitchurch, and plays a vital role in acting on behalf of the community it represents. The Council has a wide range of powers and responsibilities including: ● Administration of open spaces, play areas, bus shelters, cemeteries, allotments. ● Assessment of planning applications and other proposals which may affect the parish ● Undertaking projects and schemes that benefit local residents ● Helping other tiers of local government keep in touch with their local communities The Village Council has previously objected to the Joint Spatial Plan (JSP). Specifically, it has significant concerns about, and has objected to the allocation of a strategic development location which allocates Whitchurch as an SDL in the JSP (7.2 Whitchurch). The WVC objection to the JLTP4 is also an objection to the principle of further unnecessary road developments which is seen as a precursor to an urban extension for Bristol, within Whitchurch, which will harm the character, setting and environment of the village. The JLTP is predicated on a false premise that the strategic development locations within the JSP are required, and are identified in the best locations. They are not. The only rationale for the relief road from Hicks Gate to Whitchurch is to open up land for development. -

Lower Hawkstor Farm Hawkstor, Bodmin, Cornwall PL30 4HN

4HN PL30 Cornwall Bodmin, Hawkstor, Farm Hawkstor Lower www.kivells.com tel. 01579 384321 email [email protected] Lower Hawkstor Farm Hawkstor, Bodmin, Cornwall PL30 4HN £325,000 Detached renovated farmhouse on Bodmin Moor Character, yet double glazed, two wood burners and central heating Two reception, kitchen, utility, bathroom and three bedrooms Ample parking, plus double garage with potential and stone barns Private, yet accessible south facing site approximately 0.5 acre Property has been used for holiday letting and is fully furnished BT infinity broadband is connected Further land is available subject to moorland rights Ref: CA00004777 SITUATION DIRECTIONS Map Reference OS Land Ranger Map: 200 - 146/745. The house enjoys a sheltered From Bodmin proceed towards Launceston on the A30 road for approximately southerly aspect being less than 1/2 a mile off the A30 and accessed from a private 7 miles where at the bottom of a small hill immediately after a left hand turning to track which serves just two other dwellings. The major mid Cornwall town of St. Breward and a lay-by with picnic tables turn left onto a private road. This left Bodmin is some 7 miles to the west and provides a range of shops, services, schools, turn is also adjacent to a crossing point on the A30 dual carriageway. Proceed up etc. and access to the Camel Trail (foot/cycle path) which connects to Wadebridge this private road where within 1/2 a mile the property will be found on the right hand and Padstow. Just south of Bodmin with access off the A38 road is Bodmin Parkway side. -

Appendix 1 A303 Prospectus , Item 39. PDF 1 MB

A303 Corridor Improvement Programme (including the A358 and A30) Outline economic case and proposed next steps April 2013 HEART OF THE SOUTH WEST Local Enterprise Partnership This campaign is supported by; Cornwall Council, Plymouth Council, Torbay Council, CBI, Cornwall & Isles of Scilly LEP, Devon and Somerset Fire & Rescue Service, Authorities along the corridor (Somerset, Devon, and Wiltshire), the Foreword Highways Agency and Heart of South West Local Enterprise Partnership have collaborated to bring together a case for investment as summarised in this document. This strategy complements the National Infrastructure Plan and “The A303 acts as a beaver dam across the fl owing river Government investments to remove barriers to growth in the South West bringing people to us. We totally support the upgrading such as funding for faster broadband connectivity, improvements to the A30 of the road as we know from experience how much the (Temple) and the South Devon Link Road. A30 improvements made a difference, we know that the We are seeking a commitment from Government to progress the whole route A303 will have a similar if greater impact still.” improvement over time, based on the considerable wider economic benefi ts Sir Tim Smit KBE, Chief Executive, Development and co-founder and direct transport benefi ts it would deliver. of The Eden Project. There is a clear case for the Highways Agency to take the scheme forward as a priority within their investment programme and deliver sections of the improvement in phases. Further detailed work will be required within forthcoming Agency Route Based Studies, but we have established that many An improvement to the A303/A358/A30 corridor has long been sections of the route represent high value for money when comparing the considered a priority by a strong coalition of businesses, LEPs, local cost of the improvements to the predicted transport and wider economic authorities, emergency services and cross-party MPs who are calling benefi ts. -

East Coker Monarch's Way Walk

East Coker Monarch’s Way Walk For nearly half of its length this walk (3.9 miles, 6.3 km) follows the long distance path known as Monarch’s Way. It returns round the northern area of the parish, passing one of the oldest properties in the area. It is marked in Dark Blue on the Discover East Coker map and walkers should refer to OS Explorer Map 129 for more detail. Countryside paths can be muddy at times and waterproof footwear is advised. Park considerately and start at the Village Hall (Grid Ref. ST537128) From the Village Hall turn right into Halves Lane and immediately right into Drakes Meadow. Follow the tarmac road round to the left and right onto a footpath and turn left onto the road towards a large old building (East Coker Mill) . Before the Mill, turn right onto the footpath signposted Chapel Row 1/6 mile over a stile. Follow the right of the field to the rear of Mill Close gardens. The Pavilion and playing fields are to the left. At the next stile, turn right past Chapel Row on Long Furlong Lane. This building originally housed the East Coker Workhouse. At the T junction, turn sharp left into Burton. After the row of cottages, take the kissing gate on the right signposted Naish Priory 3/4 mile. This follows a red brick wall and then joins a track adjoining North Coker House to the right. This walled garden supplied all the needs of the house in fruit and vegetables until North Coker House was converted into apartments. -

Aug-Nov 2017

SOUTH SOMERSET GROUP www.somersetramblers.co.uk A local group of the Ramblers’ Association. Registered. Charity No.1093577. Promoting rambling, protecting rights of way, campaigning for access to open country and defending the beauty of the countryside. AUG 2017 - NOV 2017 WALKS See Stop Press on Page 7 New walk leaders are always needed. Please contact the appropriate programme secretary. Walk leaders and designated back-markers should exchange mobile phone numbers so that contact may be maintained in cases of emergency. Those leaders and back-markers without phones should appoint substitutes. Numbers should be exchanged before the walk commences. Every effort should be made to ensure a first-aid kit is available on all walks. Walks are graded according to the following classification of pace:- A = Fast B = Brisk Medium = 5-7 miles Short = 4-5 miles approx Starting times of walks vary and need to be noted carefully. NOTICES Annual General Meeting. On Sat 4th Nov East Coker Village Hall 2.00 pm. Motions and other items should be sent to the secretary by 16th October. Meet with other members in reviewing the past year and planning for the future. Area Representative and Committee members needed. Interested parties contact a committee member. Group Committee Meeting: will be held on Thu Oct 5th 2017. Programme Distribution. Short walk distribution is on 9th November and Medium walk distribution is on 16th November. Christmas Lunch. This will be held at 1.00pm on Thursday 7th December at The Muddled Man, West Chinnock. The menu and cost will be known by October 1st. -

February 2014

PROPERTY February 2014 Day 1 EXETER tuesday 18th February at 1.00pm Day 2 LONDON Wednesday 19th February at 1.00pm Day 3 MANCHESTER thursday 20th February at 1.00pm auction calendar 2014 Regional & national Jan Feb Mar apr May Jun Jul aug Sept oct nov Dec Manchester 20th 1st 22nd 15th 4th 21st 9th london 19th 2nd 21st 16th 3rd 22nd 10th Sheffield 9th 29th 17th 2nd 23rd 11th exeter 18th 8th 28th 22nd 9th 28th 16th Closing Date 13th Jan 28th Feb 17th apr 13th June 31st July 19th Sept 7th nov heaD office LOnDon office Tel: 0207 963 0628 80–86 new london Road, chelmsford exeteR Office tel: 01395 275691 essex cM2 0PD SHEFFIELD Office tel: 0114 254 1185 tel: 0870 240 1140 email: [email protected] MancheSteR Office tel: 0161 956 8999 Venues SheffielD auction lonDon auction DoubletRee by hilton LE MeRiDIEN PICCADILLY Sheffield Park, chesterfield Road South, Sheffield S8 8bW Piccadilly, london W1J 0BH MancheSteR auction exeteR auction MancheSteR uniteD Football club LTD SanDy PaRk conFeRence centRe Sir Matt busby Way, old trafford, Manchester M16 0Ra Sandy Park Way, exeter EX2 7NN Managing Director’s note hello and Welcome to the countrywide Property auctions February catalogue. i hope that your festive period was suitably merry; and that auction coordinators. they’ve been successfully auctioning like us here at countrywide, you’re raring to go for the new property in South yorkshire for the last six years and i’m year. delighted to say that i’ll be able to introduce them to you formally in March, when the april catalogue is published. -

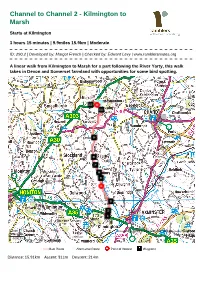

Kilmington to Marsh

Channel to Channel 2 - Kilmington to Marsh Starts at Kilmington 3 hours 15 minutes | 9.9miles 15.9km | Moderate ID: 290.2 | Developed by: Margot French | Checked by: Edward Levy | www.ramblersroutes.org A linear walk from Kilmington to Marsh for a part following the River Yarty, this walk takes in Devon and Somerset farmland with opportunities for some bird spotting. 1000 © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100033886 m Scale = 1 : 108K 5000 ft Main Route Alternative Route Point of Interest Waypoint Distance: 15.91km Ascent: 311m Descent: 214m Route Profile 200 150 100 Height (m) Height 50 0 0.0 0.8 1.8 2.8 3.8 4.6 5.6 6.6 7.4 8.3 9.1 9.8 10.8 11.8 12.8 13.6 14.4 15.1 15.9 *move mouse over graph to see points on route The Ramblers is Britain’s walking charity. We work to safeguard the footpaths, countryside and other places where we all go walking. We encourage people to walk for their health and wellbeing. To become a member visit www.ramblers.org.uk Starts at The Old Inn, Kilmington, Axminster, Devon. EX13 7RB Ends at The Flintlock Inn, Marsh, Honiton, Devon. EX14 9AJ Getting there The start at Kilmington can be accessed by Stagecoach bus route 380 running between Axminster and Honiton. There is one bus only per week on a Tuesday to Marsh and returning to Honiton. It's timing in the middle of the day makes it unsuitable for travel at the end of the walk. -

A358 Taunton to Southfields Dualling Scheme

A358 Taunton to Southfields Dualling Scheme Environmental Impact Assessment Scoping Report - Volume 1: Main Report HE551508-ARP-EGN-ZZ-RP-LE-000001 23/03/21 A358 Taunton to Southfields Dualling Scheme | HE551508 Highways England Table of contents Pages 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Purpose of the report 1 1.2 Overview of the proposed scheme 2 1.3 Legislative context and the need for environmental impact assessment 3 1.4 Planning policy context 3 2 The proposed scheme 5 2.1 Need for the proposed scheme 5 2.2 Proposed Scheme objectives 6 2.3 Proposed Scheme location 7 2.4 Proposed scheme description 10 2.5 Construction 18 3 Assessment of alternatives 21 3.1 Assessment methodology 21 3.2 Stages 0 and 1 options appraised 22 3.3 Stage 2 Further assessment of selected options 24 4 Consultation 32 4.1 Consultation undertaken to date 32 4.2 Proposed consultation 33 5 Environmental assessment methodology 35 5.1 Approach to aspects of EIA regulations 35 5.2 Surveys and predictive techniques and methods 39 5.3 General assessment assumptions and limitations 41 5.4 Mitigation and enhancement 41 5.5 Significance criteria 42 5.6 Cumulative effects 43 5.7 Supporting assessments 44 5.8 Environmental Statement 45 6 Air quality 47 6.1 NPSNN requirements 47 6.2 Study area 48 6.3 Baseline conditions 49 6.4 Potential impacts 52 6.5 Design, mitigation and enhancement measures 54 6.6 Description of the likely significant effects 54 6.7 Assessment methodology 56 6.8 Assessment assumptions and limitations 62 A358 Taunton to Southfields Dualling Scheme | HE551508 Highways -

Environmental Appraisal Report

St. Austell Link Road Environmental Appraisal Report CORMAC Project number: 60571547 20th August 2020 St. Austell Link Road Full Business Case Project number: 60571547 Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Sarah Roberts Steffan Shageer Alison Morrissy Graduate Environmental Principal Environmental Associate Director Consultant Consultant Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorised Name Position 1 20/06/19 Template Y SS Principal 2 11/07/09 FINAL Y AM Associate 3 20/08/20 FINAL Y SS Principal 4 Prepared for: CORMAC AECOM 1 St. Austell Link Road Full Business Case Project number: 60571547 Prepared for: CORMAC Prepared by: AECOM Limited Plumer House Third Floor, East Wing Tailyour Road Crownhill Plymouth PL6 5DH United Kingdom T: +44 (1752) 676700 aecom.com © 2019 AECOM Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Prepared for: CORMAC AECOM 2 St. Austell Link Road Full Business Case Project number: 60571547 Table of Contents 1. Introduction...................................................................................................6 -

Hayle Masterplan Consultation Report

Information Classification: PUBLIC Hayle Masterplan Consultation Report December 2019 Information Classification: PUBLIC Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 Statement of Community Involvement ...................................................................... 2 Sustainability Appraisal .............................................................................................. 3 Public Consultation & Responses received .................................................................... 4 Hayle Masterplan Document ...................................................................................... 4 Statutory consultees – Summary of Responses ......................................................... 7 Specific questions – Summary of Responses ........................................................... 13 Appendix 1: Newspaper Notice .................................................................................... 19 Appendix 2: List of Statutory consultees and other organisations .............................. 21 Appendix 3: Consultation Responses ........................................................................... 23 Statutory Consultees ................................................................................................ 23 All other comments .................................................................................................. 39 Hayle Draft Masterplan Consultation Report December 2019 1 Information