Butterfly Report.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

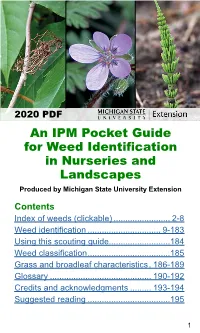

An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension

Back to table of contents Back to index 2020 PDF An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension Contents Index of weeds (clickable) ........................ 2-8 Weed identification ............................... 9-183 Using this scouting guide..........................184 Weed classification ...................................185 Grass and broadleaf characteristics . 186-189 Glossary ........................................... 190-192 Credits and acknowledgments ......... 193-194 Suggested reading ...................................195 1 Back to table of contents Back to index Index By common name Annual bluegrass ...........................................32-33 Annual sowthistle................................................73 Asiatic (common) dayflower ..........................18-19 Barnyardgrass ....................................................27 Bindweed, field ..........................................101-103 Bindweed, hedge .......................................102-103 Birdseye pearlwort ..............................................98 Birdsfoot trefoil...........................................109-110 Bittercress, hairy ............................................83-85 Bittercress, smallflowered...................................85 Black medic ............................................... 112-113 Blackseed plantain ...........................................150 Bluegrass, annual ..........................................32-33 Brambles ...................................................164-165 -

Depositing Archaeological Archives

Hampshire County Council Arts & Museums Service Archaeology Section Depositing Archaeological Archives Version 2.3 October 2012 Contents Contact information 1. Notification 2. Transfer of Title 3. Selection, Retention and Disposal 4. Packaging 5. Numbering and Labelling 6. Conservation 7. Documentary Archives 8. Transference of the Archive 9. Publications 10. Storing the Archive. Appendix 1 Archaeology Collections. Appendix 2 Collecting Policy (Archaeology). Appendix 3 Notification and Transfer Form. Appendix 4 Advice on Packaging. Appendix 5 Advice on marking, numbering and labelling. Appendix 6 Advice on presenting the Documentary Archive. Appendix 7 Storage Charge Contact us Dave Allen Keeper of Archaeology Chilcomb House, Chilcomb Lane, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 8RD. [email protected] Telephone: 01962 826738 Fax: 01962 869836 Location map http://www3.hants.gov.uk/museum/museum-finder/about-museumservice/map- chilcomb.htm Introduction Hampshire County Council Arts & Museums Service (hereafter the HCCAMS) is part of the Culture, Communities & Business Services Department of the County Council. The archaeology stores are located at the Museum headquarters at Chilcomb House, on the outskirts of Winchester, close to the M3 (see above). The museum collections are divided into four main areas, Archaeology, Art, Hampshire History and Natural Sciences. The Archaeology collection is already substantial, and our existing resources are committed to ongoing maintenance and improving accessibility and storage conditions for this material. In common with other services across the country, limited resources impact on our storage capacity. As such, it is important that any new accessions relate to the current collecting policy (Appendix 2). This document sets out the requirements governing the deposition of archaeological archives with the HCCAMS. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

M25 to Solent Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1

M25 to Solent Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of Route Strategies 2 Strategic themes 2 Stakeholder engagement 3 Transport Focus 3 2. The route 5 Route Strategy overview map 7 3. Current constraints and challenges 9 A safe and serviceable network 9 More free-flowing network 9 Supporting economic growth 10 An improved environment 10 A more accessible and integrated network 10 Diversionary routes 13 Maintaining the strategic road network 14 4. Current investment plans and growth potential 15 Economic context 15 Innovation 15 Investment plans 15 5. Future challenges and opportunities 19 6. Next steps 23 i R Lon ou don to Scotla te nd East London Or bital and M23 to Gatwick str Lon ategies don to Scotland West London to Wales The division of rou tes for the F progra elixstowe to Midlands mme of route strategies on t he Solent to Midlands Strategic Road Network M25 to Solent (A3 and M3) Kent Corridor to M25 (M2 and M20) South Coast Central Birmingham to Exeter A1 South West Peninsula London to Leeds (East) East of England South Pennines A19 A69 North Pen Newccaastlstlee upon Tyne nines Carlisle A1 Sunderland Midlands to Wales and Gloucest M6 ershire North and East Midlands A66 A1(M) A595 South Midlands Middlesbrougugh A66 A174 A590 A19 A1 A64 A585 M6 York Irish S Lee ea M55 ds M65 M1 Preston M606 M621 A56 M62 A63 Kingston upon Hull M62 M61 M58 A1 M1 Liver Manchest A628 A180 North Sea pool er M18 M180 Grimsby M57 A616 A1(M) M53 M62 M60 Sheffield A556 M56 M6 A46 A55 A1 Lincoln A500 Stoke-on-Trent A38 M1 Nottingham -

Butterfly Monitoring Scheme

BUTTERFLY MONITORING SCHEME Report to recorders 1999 INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) The Butterfly Monitoring Scheme Report to Recorders 1999 J NICK GREATOREX-DAVIES & DAVID B ROY ITE Monks Wood Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs PE17 2LS March 2000 CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Summary of the 1999 season 3 Percentage of counts completed 7 The proportion of annual indices calculated 8 Annual indices for the scarcer species 9 The number of weeks recorded for each site 10 Map showing the BMS regions and the distribution of monitored sites 11 The number of sites contributing data to the BMS 12 Comparison of the 24 years of the BMS 13 Numbers of butterflies recorded 14 Summary of changes at site level 1998-99 16 Individual species accounts 18 Publications in 1999/2000 29 Publications due in 2000 29 References 29 Acknowledgements 29 Appendix I: Graphs showing fluctuations in all-sites indices for 34 species 31 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1 The number of sites with completed transects in each recording week in 7 1998 2 The number of sites with completed transects in each recording week in 7 1999 3 The number of annual indices calculated for the scarcer species compared 9 with the number of sites where the species was actually recorded in 1998 4 The number of weeks recorded for each transect in 1998 10 5 The number of weeks recorded for each transect in 1999 10 6 The number of sites contributing data to the scheme. 12 7 Comparison of the years 1979-1999 for butterflies 13 8 a-d Log collated indices 1976-99 -

Dragonflies and Damselflies in Your Garden

Natural England works for people, places and nature to conserve and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and wildlife in rural, urban, coastal and marine areas. Dragonflies and www.naturalengland.org.uk © Natural England 2007 damselflies in your garden ISBN 978-1-84754-015-7 Catalogue code NE21 Written by Caroline Daguet Designed by RR Donnelley Front cover photograph: A male southern hawker dragonfly. This species is the one most commonly seen in gardens. Steve Cham. www.naturalengland.org.uk Dragonflies and damselflies in your garden Dragonflies and damselflies are Modern dragonflies are tiny by amazing insects. They have a long comparison, but are still large and history and modern species are almost spectacular enough to capture the identical to ancestors that flew over attention of anyone walking along a prehistoric forests some 300 million river bank or enjoying a sunny years ago. Some of these ancient afternoon by the garden pond. dragonflies were giants, with This booklet will tell you about the wingspans of up to 70 cm. biology and life-cycles of dragonflies and damselflies, help you to identify some common species, and tell you how you can encourage these insects to visit your garden. Male common blue damselfly. Most damselflies hold their wings against their bodies when at rest. BDS Dragonflies and damselflies belong to Dragonflies the insect order known as Odonata, Dragonflies are usually larger than meaning ‘toothed jaws’. They are often damselflies. They are stronger fliers and referred to collectively as ‘dragonflies’, can often be found well away from but dragonflies and damselflies are two water. When at rest, they hold their distinct groups. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

SPRING AUCTION 2021 Welcome to Our Spring Auction

Spring Auction BID TO GIVE BUTTERFLIES & MOTHS A BOOST - SPRING AUCTION 2021 Welcome to our Spring Auction 22nd February - April 9th 2021 We have over 60 unique and exciting experiences and items available in our Spring Auction. There is something for everyone, whether you fancy a weekend away to spot the British Swallowtail, would rather relax with family or friends over an eco cheese tasting experience, or want to try moth trapping in your own garden. Plus we’ve also got a wonderful array of art, items to help keep the kids entertained and some beautiful pieces of jewellery, including a brooch from actress Joanna Lumley’s personal collection. By taking part, you’ll be helping us to celebrate wildlife, champion conservation and help ensure butterflies and moths can thrive long into the future. Explore the wonderful items available in this booklet or visit https:// givergy.uk/ButterflyConservation If you do not have access to the internet but would like to make a bid, please phone us on 01929 400209. Lot 1 British Swallowtail Weekend Break Donated by Greenwings Lot 2 Classic car experience, stay & wildlife walk Donated by Maurice Avent Lot 3 Four-night Kendal break with butterfly tours Donated by Chris & Claire Winnick Lot 4 Purple Emperor Butterfly Safari for two Donated by Knepp Lot 5 Marsh Fritillary walk with BC scientist for 6 Donated by Butterfly Conservation Lot 6 Cryptic Wood White walk in N. Ireland for 6 Donated by Butterfly Conservation Lot 7 A champagne tour of Spencer House for six Donated by Spencer House Lot 8 Bombay Sapphire gin masterclass for 2 people Donated by Bombay Sapphire Lot 9 Golf for four people at Cumberwell Park Donated by Cumberwell Park Lot 10 Online eco cheese tasting experience for 6 Donated by Cambridge Cheese Co. -

The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011

EEA Technical report No 11/2013 The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011 ISSN 1725-2237 EEA Technical report No 11/2013 The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011 Cover design: EEA Cover photo © Chris van Swaay, Orangetip (Anthocharis cardamines) Layout: EEA/Pia Schmidt Copyright notice © European Environment Agency, 2013 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Information about the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 ISBN 978-92-9213-402-0 ISSN 1725-2237 doi:10.2800/89760 REG.NO. DK-000244 European Environment Agency Kongens Nytorv 6 1050 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel.: +45 33 36 71 00 Fax: +45 33 36 71 99 Web: eea.europa.eu Enquiries: eea.europa.eu/enquiries Contents Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Summary .................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 9 2 Building the European Grassland Butterfly Indicator ........................................... 12 Fieldwork .............................................................................................................. 12 Grassland butterflies ............................................................................................. -

Summer Moths

The group of members at Holtspur who had just been clearing scrub, refreshing the information boards, clearing the footpath of obstructions, removing seedling shrubs from the ‘wrong place’ and planted them into the central hedge and the windbreak on Lower Field, clearing dogwood from Triangle Bank, making a small scallop into the top hedge, checking wobbly posts and making repairs to the fencing. Nick Bowles Planting disease resistant elms in the Planting disease resistant elms in Lye Valley, Oxon - in the rain! Bottom Wood, Bucks. Peter Cuss Peter Cuss I will be pleased to see the spring (which seems very slow to arrive this year) for a variety of reasons. One, is to relax after the large number of work parties. I haven’t kept a list of the number of the tasks we attended in previous winters but this year we advertised and we had members working at 46 conservation tasks. As a group of people that love butterflies and moths (and therefore cherish the places in which they live) we can take pride and feel relief, that our expertise has positively influenced the management of those places. Our volunteers have acted to halt, and hopefully reverse, the decline in numbers and their efforts have been magnificent. Our Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/Butterflies.Berkshire.Buckinghamshire.Oxfordshire/)bears witness to the large numbers of members involved. Furthermore, I haven’t included events such as Elm tree planting (by small groups of members), the nurturing of seedlings by many members, the preparation of display board information for our reserve and a number of other largely individual acts which took place during the same winter season. -

Introduction

BULGARIA Nick Greatorex-Davies. European Butterflies Group Contact ([email protected]) Local Contact Prof. Stoyan Beshkov. ([email protected]) National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Sofia, Butterfly Conservation Europe Partner Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Stanislav Abadjiev compiled and collated butterfly records for the whole of Bulgaria and published a Local Recording Scheme distribution atlas in 2001 (see below). Records are still being gathered and can be sent to Stoyan Beshkov at NMNH, Sofia. Butterfly List See Butterflies of Bulgaria website (Details below) Introduction Bulgaria is situated in eastern Europe with its eastern border running along the Black Sea coast. It is separated from Romania for much of its northern border by the River Danube. It shares its western border with Serbia and Macedonia, and its southern border with Greece and Turkey. Bulgaria has a land area of almost 111,000 sq km (smaller than England but bigger than Scotland) and a declining human population of 7.15 million (as of 2015), 1.5 million of which live in the capital city, Sofia. It is very varied in both climate, topography and habitats. Substantial parts of the country are mountainous, particularly in the west, south-west and central ‘spine’ of the country and has the highest mountain in the Balkan Mountains (Musala peak in the Rila Mountains, 2925m) (Map 1). Almost 70% of the land area is above 200m and over 27% above 600m. About 40% of the country is forested and this is likely to increase through natural regeneration due to the abandonment of agricultural land. Following nearly 500 years under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria was independent for just a few years from 1908 before coming under the domination of the soviet communist regime in 1946. -

Lower Hawkstor Farm Hawkstor, Bodmin, Cornwall PL30 4HN

4HN PL30 Cornwall Bodmin, Hawkstor, Farm Hawkstor Lower www.kivells.com tel. 01579 384321 email [email protected] Lower Hawkstor Farm Hawkstor, Bodmin, Cornwall PL30 4HN £325,000 Detached renovated farmhouse on Bodmin Moor Character, yet double glazed, two wood burners and central heating Two reception, kitchen, utility, bathroom and three bedrooms Ample parking, plus double garage with potential and stone barns Private, yet accessible south facing site approximately 0.5 acre Property has been used for holiday letting and is fully furnished BT infinity broadband is connected Further land is available subject to moorland rights Ref: CA00004777 SITUATION DIRECTIONS Map Reference OS Land Ranger Map: 200 - 146/745. The house enjoys a sheltered From Bodmin proceed towards Launceston on the A30 road for approximately southerly aspect being less than 1/2 a mile off the A30 and accessed from a private 7 miles where at the bottom of a small hill immediately after a left hand turning to track which serves just two other dwellings. The major mid Cornwall town of St. Breward and a lay-by with picnic tables turn left onto a private road. This left Bodmin is some 7 miles to the west and provides a range of shops, services, schools, turn is also adjacent to a crossing point on the A30 dual carriageway. Proceed up etc. and access to the Camel Trail (foot/cycle path) which connects to Wadebridge this private road where within 1/2 a mile the property will be found on the right hand and Padstow. Just south of Bodmin with access off the A38 road is Bodmin Parkway side.