Colias Ponteni 47 Years of Investigation, Thought and Speculations Over a Butterfly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

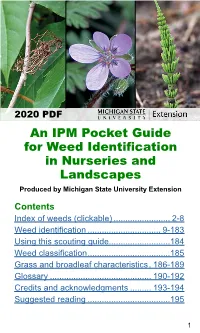

An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension

Back to table of contents Back to index 2020 PDF An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension Contents Index of weeds (clickable) ........................ 2-8 Weed identification ............................... 9-183 Using this scouting guide..........................184 Weed classification ...................................185 Grass and broadleaf characteristics . 186-189 Glossary ........................................... 190-192 Credits and acknowledgments ......... 193-194 Suggested reading ...................................195 1 Back to table of contents Back to index Index By common name Annual bluegrass ...........................................32-33 Annual sowthistle................................................73 Asiatic (common) dayflower ..........................18-19 Barnyardgrass ....................................................27 Bindweed, field ..........................................101-103 Bindweed, hedge .......................................102-103 Birdseye pearlwort ..............................................98 Birdsfoot trefoil...........................................109-110 Bittercress, hairy ............................................83-85 Bittercress, smallflowered...................................85 Black medic ............................................... 112-113 Blackseed plantain ...........................................150 Bluegrass, annual ..........................................32-33 Brambles ...................................................164-165 -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Orange Sulphur, Colias Eurytheme, on Boneset

Orange Sulphur, Colias eurytheme, on Boneset, Eupatorium perfoliatum, In OMC flitrh Insect Survey of Waukegan Dunes, Summer 2002 Including Butterflies, Dragonflies & Beetles Prepared for the Waukegan Harbor Citizens' Advisory Group Jean B . Schreiber (Susie), Chair Principal Investigator : John A. Wagner, Ph . D . Associate, Department of Zoology - Insects Field Museum of Natural History 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 Telephone (708) 485 7358 home (312) 665 7016 museum Email jwdw440(q-), m indsprinq .co m > home wagner@,fmnh .orq> museum Abstract: From May 10, 2002 through September 13, 2002, eight field trips were made to the Harbor at Waukegan, Illinois to survey the beach - dunes and swales for Odonata [dragonfly], Lepidoptera [butterfly] and Coleoptera [beetles] faunas between Midwest Generation Plant on the North and the Outboard Marine Corporation ditch at the South . Eight species of Dragonflies, fourteen species of Butterflies, and eighteen species of beetles are identified . No threatened or endangered species were found in this survey during twenty-four hours of field observations . The area is undoubtedly home to many more species than those listed in this report. Of note, the endangered Karner Blue butterfly, Lycaeides melissa samuelis Nabakov was not seen even though it has been reported from Illinois Beach State Park, Lake County . The larval food plant, Lupinus perennis, for the blue was not observed at Waukegan. The limestone seeps habitat of the endangered Hines Emerald dragonfly, Somatochlora hineana, is not part of the ecology here . One surprise is the. breeding population of Buckeye butterflies, Junonia coenid (Hubner) which may be feeding on Purple Loosestrife . The specimens collected in this study are deposited in the insect collection at the Field Museum . -

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis Samantha Lynn Davis Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Repository Citation Davis, Samantha Lynn, "Evaluating Threats to the Rare Butterfly, Pieris Virginiensis" (2015). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1433. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Samantha L. Davis B.S., Daemen College, 2010 2015 Wright State University Wright State University GRADUATE SCHOOL May 17, 2015 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY Samantha L. Davis ENTITLED Evaluating threats to the rare butterfly, Pieris virginiensis BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Don Cipollini, Ph.D. Director, Environmental Sciences Ph.D. Program Robert E.W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination John Stireman, Ph.D. Jeff Peters, Ph.D. Thaddeus Tarpey, Ph.D. Francie Chew, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Davis, Samantha. Ph.D., Environmental Sciences Ph.D. -

Superior National Forest

Admirals & Relatives Subfamily Limenitidinae Skippers Family Hesperiidae £ Viceroy Limenitis archippus Spread-wing Skippers Subfamily Pyrginae £ Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus clarus £ Dreamy Duskywing Erynnis icelus £ Juvenal’s Duskywing Erynnis juvenalis £ Northern Cloudywing Thorybes pylades Butterflies of the £ White Admiral Limenitis arthemis arthemis Superior Satyrs Subfamily Satyrinae National Forest £ Common Wood-nymph Cercyonis pegala £ Common Ringlet Coenonympha tullia £ Northern Pearly-eye Enodia anthedon Skipperlings Subfamily Heteropterinae £ Arctic Skipper Carterocephalus palaemon £ Mancinus Alpine Erebia disa mancinus R9SS £ Red-disked Alpine Erebia discoidalis R9SS £ Little Wood-satyr Megisto cymela Grass-Skippers Subfamily Hesperiinae £ Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon £ Macoun’s Arctic Oeneis macounii £ Common Roadside-Skipper Amblyscirtes vialis £ Jutta Arctic Oeneis jutta (R9SS) £ Least Skipper Ancyloxypha numitor Northern Crescent £ Eyed Brown Satyrodes eurydice £ Dun Skipper Euphyes vestris Phyciodes selenis £ Common Branded Skipper Hesperia comma £ Indian Skipper Hesperia sassacus Monarchs Subfamily Danainae £ Hobomok Skipper Poanes hobomok £ Monarch Danaus plexippus £ Long Dash Polites mystic £ Peck’s Skipper Polites peckius £ Tawny-edged Skipper Polites themistocles £ European Skipper Thymelicus lineola LINKS: http://www.naba.org/ The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/ in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national -

Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health

EN65CH11_Cameron ARjats.cls December 18, 2019 20:52 Annual Review of Entomology Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health Sydney A. Cameron1,∗ and Ben M. Sadd2 1Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; email: [email protected] 2School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020. 65:209–32 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on Bombus, pollinator, status, decline, conservation, neonicotinoids, pathogens October 14, 2019 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Bumble bees (Bombus) are unusually important pollinators, with approx- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118- imately 260 wild species native to all biogeographic regions except sub- 111847 Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As they are vitally important in Copyright © 2020 by Annual Reviews. natural ecosystems and to agricultural food production globally, the increase Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020.65:209-232. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved in reports of declining distribution and abundance over the past decade ∗ Corresponding author has led to an explosion of interest in bumble bee population decline. We Access provided by University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign on 02/11/20. For personal use only. summarize data on the threat status of wild bumble bee species across bio- geographic regions, underscoring regions lacking assessment data. Focusing on data-rich studies, we also synthesize recent research on potential causes of population declines. There is evidence that habitat loss, changing climate, pathogen transmission, invasion of nonnative species, and pesticides, oper- ating individually and in combination, negatively impact bumble bee health, and that effects may depend on species and locality. -

INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a Synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a Historical Sketch

ZOOLOGÍA-TAXONOMÍA www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm Caldasia 31(2):407-440. 2009 HACIA UNA SÍNTESIS DE LOS PAPILIONOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a historical sketch JOSÉ LUIS SALINAS-GUTIÉRREZ El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] CLAUDIO MÉNDEZ Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos, Ciudad Universitaria, Campus Central USAC, Zona 12. Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] MERCEDES BARRIOS Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (CECON), Universidad de San Carlos, Avenida La Reforma 0-53, Zona 10, Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] CARMEN POZO El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] JORGE LLORENTE-BOUSQUETS Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Apartado Postal 70-399, México D.F. 04510; México. [email protected]. Autor responsable. RESUMEN La riqueza biológica de Mesoamérica es enorme. Dentro de esta gran área geográfi ca se encuentran algunos de los ecosistemas más diversos del planeta (selvas tropicales), así como varios de los principales centros de endemismo en el mundo (bosques nublados). Países como Guatemala, en esta gran área biogeográfi ca, tiene grandes zonas de bosque húmedo tropical y bosque mesófi lo, por esta razón es muy importante para analizar la diversidad en la región. Lamentablemente, la fauna de mariposas de Guatemala es poco conocida y por lo tanto, es necesario llevar a cabo un estudio y análisis de la composición y la diversidad de las mariposas (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) en Guatemala. -

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

J OURNAL OF T HE L EPIDOPTERISTS’ S OCIETY Volume 62 2008 Number 2 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 61(2), 2007, 61–66 COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON THE IMMATURE STAGES AND DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY OF FIVE ARGYNNIS SPP. (SUBGENUS SPEYERIA) (NYMPHALIDAE) FROM WASHINGTON DAVID G. JAMES Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, 24105 North Bunn Road, Prosser, Washington 99350; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Comparative illustrations and notes on morphology and biology are provided on the immature stages of five Arg- ynnis spp. (A. cybele leto, A. coronis simaetha, A. zerene picta, A. egleis mcdunnoughi, A. hydaspe rhodope) found in the Pacific Northwest. High quality images allowed separation of the five species in most of their immature stages. Sixth instars of all species possessed a fleshy, eversible osmeterium-like gland located ventrally between the head and first thoracic segment. Dormant first in- star larvae of all species exposed to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination), 2.0–2.5 months after hatch- ing, did not feed and died within 6–9 days, indicating the larvae were in diapause. Overwintering of first instars for ~ 80 days in dark- ness at 5 ± 0.5º C, 75 ± 5% r.h. resulted in minimal mortality. Subsequent exposure to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination) resulted in breaking of dormancy and commencement of feeding in all species within 2–5 days. Durations of individual instars and complete post-larval feeding development durations were similar for A. coronis, A. zerene, A. egleis and A. -

Jammu and Kashmir) of India Anu Bala*, J

International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies (IJIMS), 2014, Vol 1, No.7, 24-34. 24 Available online at http://www.ijims.com ISSN: 2348 – 0343 Butterflies of family Pieridae reported from Jammu region (Jammu and Kashmir) of India Anu Bala*, J. S. Tara and Madhvi Gupta Department of Zoology, University of Jammu Jammu-180,006, India *Corresponding author: Anu Bala Abstract The present article incorporates detailed field observations of family Pieridae in Jammu region at different altitudes during spring, summer and autumn seasons of 2012-2013. The study revealed that 13 species of butterflies belonging to 10 genera of family Pieridae exist in the study area. Most members of Family Pieridae are white or yellow. Pieridae is a large family of butterflies with about 76 genera containing approximately 1,100 species mostly from tropical Africa and Asia. Keywords :Butterflies, India, Jammu, Pieridae. Introduction Jammu and Kashmir is the northernmost state of India. It consists of the district of Bhaderwah, Doda, Jammu, Kathua, Kishtwar, Poonch, Rajouri, Ramban, Reasi, Samba and Udhampur. Most of the area of the region is hilly and Pir Panjal range separates it from the Kashmir valley and part of the great Himalayas in the eastern districts of Doda and Kishtwar. The main river is Chenab. Jammu borders Kashmir to the north, Ladakh to the east and Himachal Pradesh and Punjab to the south. In east west, the line of control separates Jammu from the Pakistan region called POK. The climate of the region varies with altitude. The order Lepidoptera contains over 19,000 species of butterflies and 100,000 species of moths worldwide. -

Highlights in the History of Entomology in Hawaii 1778-1963

Pacific Insects 6 (4) : 689-729 December 30, 1964 HIGHLIGHTS IN THE HISTORY OF ENTOMOLOGY IN HAWAII 1778-1963 By C. E. Pemberton HONORARY ASSOCIATE IN ENTOMOLOGY BERNICE P. BISHOP MUSEUM PRINCIPAL ENTOMOLOGIST (RETIRED) EXPERIMENT STATION, HAWAIIAN SUGAR PLANTERS' ASSOCIATION CONTENTS Page Introduction 690 Early References to Hawaiian Insects 691 Other Sources of Information on Hawaiian Entomology 692 Important Immigrant Insect Pests and Biological Control 695 Culex quinquefasciatus Say 696 Pheidole megacephala (Fabr.) 696 Cryptotermes brevis (Walker) 696 Rhabdoscelus obscurus (Boisduval) 697 Spodoptera exempta (Walker) 697 Icerya purchasi Mask. 699 Adore tus sinicus Burm. 699 Peregrinus maidis (Ashmead) 700 Hedylepta blackburni (Butler) 700 Aedes albopictus (Skuse) 701 Aedes aegypti (Linn.) 701 Siphanta acuta (Walker) 701 Saccharicoccus sacchari (Ckll.) 702 Pulvinaria psidii Mask. 702 Dacus cucurbitae Coq. 703 Longuiungis sacchari (Zehnt.) 704 Oxya chinensis (Thun.) 704 Nipaecoccus nipae (Mask.) 705 Syagrius fulvitarsus Pasc. 705 Dysmicoccus brevipes (Ckll.) 706 Perkinsiella saccharicida Kirk. 706 Anomala orientalis (Waterhouse) 708 Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki 710 Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) 710 690 Pacific Insects Vol. 6, no. 4 Tarophagus proserpina (Kirk.) 712 Anacamptodes fragilaria (Grossbeck) 713 Polydesma umbricola Boisduval 714 Dacus dorsalis Hendel 715 Spodoptera mauritia acronyctoides (Guenee) 716 Nezara viridula var. smaragdula (Fab.) 717 Biological Control of Noxious Plants 718 Lantana camara var. aculeata 119 Pamakani,