Arxiv:1208.1409V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 7 Aug 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observational Studies of the Galaxy Peculiar Velocity Field

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES OF THE GALAXY PECULIAR VELOCITY FIELD by Philip Andrew James Astrophysics Group Blackett Laboratory Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine London SW7 2BZ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London and for the Diploma of Imperial College November 1988 1 ABSTRACT This thesis describes two observational studies of the peculiar velocity field of galaxies over scales of 50-100 Jr1 Mpc, and the consequences of these measurements for cosmological theories. An introduction is given to observational cosmology, emphasising the crucial questions of the nature of the dark matter and the formation of structure. The principal cosmological models are discussed, and the role of observations in developing these models is stressed. Consideration is given to those observations that are likely to prove good discriminators between the competing models, particular emphasis being given to studies of the coherent velocities of samples of galaxies. The first new study presented here uses optical photometry and redshifts, from the literature, for First Ranked Cluster Galaxies (FRCG’s). These galaxies are excellent standard candles, and thus ideal for peculiar velocity studies. A simple one dimensional analysis detects no relative motion between the Local Group of galaxies and 60 FRCG’s with redshifts of up to 15000 kms-1. This is shown to imply a streaming motion of the cluster galaxies of at least 600 kms_1 relative to the CBR. The second observational study is a reanalysis of the Rubin et al. (1976a,b) sample of Sc galaxies. Near-IR photometry is used in our reanalysis to minimise the effects of extinction and to facilitate the use of luminosity indicators in reducing the effects of selection biases. -

A DEEP SEARCH for PROMPT RADIO EMISSION from THERMONUCLEAR SUPERNOVAE with the VERY LARGE ARRAY Laura Chomiuk1,11, Alicia M

Draft version July 1, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 A DEEP SEARCH FOR PROMPT RADIO EMISSION FROM THERMONUCLEAR SUPERNOVAE WITH THE VERY LARGE ARRAY Laura Chomiuk1;11, Alicia M. Soderberg2, Roger A. Chevalier3, Seth Bruzewski1, Ryan J. Foley4,5, Jerod Parrent2, Jay Strader1, Carles Badenes6 Claes Fransson7 Atish Kamble2, Raffaella Margutti8, Michael P. Rupen9, & Joshua D. Simon10 Draft version July 1, 2018 ABSTRACT Searches for circumstellar material around Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) are one of the most powerful tests of the nature of SN Ia progenitors, and radio observations provide a particularly sensitive probe of this material. Here we report radio observations for SNe Ia and their lower-luminosity thermonu- clear cousins. We present the largest, most sensitive, and spectroscopically diverse study of prompt (∆t . 1 yr) radio observations of 85 thermonuclear SNe, including 25 obtained by our team with the unprecedented depth of the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. With these observations, SN 2012cg joins SN 2011fe and SN 2014J as a SN Ia with remarkably deep radio limits and excellent temporal −1 _ −9 M yr coverage (six epochs, spanning 5{216 days after explosion, yielding M=vw . 5 × 10 100 km s−1 , assuming B = 0:1 and e = 0:1). All observations yield non-detections, placing strong constraints on the presence of circumstellar material. We present analytical models for the temporal and spectral evolution of prompt radio emission from thermonuclear SNe as expected from interaction with either wind-stratified or uniform density media. These models allow us to constrain the progenitor mass loss rates, with limits ranging _ −9 −4 −1 −1 from M . -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

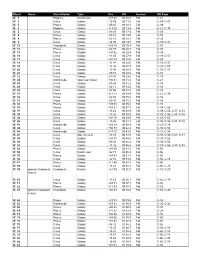

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

A Classical Morphological Analysis of Galaxies in the Spitzer Survey Of

Accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 03/07/07 A CLASSICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF GALAXIES IN THE SPITZER SURVEY OF STELLAR STRUCTURE IN GALAXIES (S4G) Ronald J. Buta1, Kartik Sheth2, E. Athanassoula3, A. Bosma3, Johan H. Knapen4,5, Eija Laurikainen6,7, Heikki Salo6, Debra Elmegreen8, Luis C. Ho9,10,11, Dennis Zaritsky12, Helene Courtois13,14, Joannah L. Hinz12, Juan-Carlos Munoz-Mateos˜ 2,15, Taehyun Kim2,15,16, Michael W. Regan17, Dimitri A. Gadotti15, Armando Gil de Paz18, Jarkko Laine6, Kar´ın Menendez-Delmestre´ 19, Sebastien´ Comeron´ 6,7, Santiago Erroz Ferrer4,5, Mark Seibert20, Trisha Mizusawa2,21, Benne Holwerda22, Barry F. Madore20 Accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series ABSTRACT The Spitzer Survey of Stellar Structure in Galaxies (S4G) is the largest available database of deep, homogeneous middle-infrared (mid-IR) images of galaxies of all types. The survey, which includes 2352 nearby galaxies, reveals galaxy morphology only minimally affected by interstellar extinction. This paper presents an atlas and classifications of S4G galaxies in the Comprehensive de Vaucouleurs revised Hubble-Sandage (CVRHS) system. The CVRHS system follows the precepts of classical de Vaucouleurs (1959) morphology, modified to include recognition of other features such as inner, outer, and nuclear lenses, nuclear rings, bars, and disks, spheroidal galaxies, X patterns and box/peanut structures, OLR subclass outer rings and pseudorings, bar ansae and barlenses, parallel sequence late-types, thick disks, and embedded disks in 3D early-type systems. We show that our CVRHS classifications are internally consistent, and that nearly half of the S4G sample consists of extreme late-type systems (mostly bulgeless, pure disk galaxies) in the range Scd-Im. -

Upper Limits on Very-High-Energy Gamma-Ray Emission from Core-Collapse Supernovae Observed with HESS

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. arxiv_submission c ESO 2019 April 25, 2019 Upper Limits on Very-High-Energy Gamma-ray Emission from Core-Collapse Supernovae Observed with H.E.S.S. H.E.S.S. Collaboration, H. Abdalla1, F. Aharonian3; 4; 5, F. Ait Benkhali3, E.O. Angüner19, M. Arakawa39, C. Arcaro1, C. Armand23, H. Ashkar17, M. Backes8; 1, V. Barbosa Martins35, M. Barnard1, Y. Becherini10, D. Berge35, K. Bernlöhr3, R. Blackwell13, M. Böttcher1, C. Boisson14, J. Bolmont15, S. Bonnefoy35, J. Bregeon16, M. Breuhaus3, F. Brun17, P. Brun17, M. Bryan9, M. Büchele34, T. Bulik18, T. Bylund10, M. Capasso27, S. Caroff15, A. Carosi23, S. Casanova20; 3, M. Cerruti15; 44, N. Chakraborty3, T. Chand1, S. Chandra1, R.C.G. Chaves16; 21, A. Chen22, S. Colafrancesco22 y, M. Curylo36, I.D. Davids8, C. Deil3, J. Devin25, P. deWilt13, L. Dirson2, A. Djannati-Ataï29, A. Dmytriiev14, A. Donath3, V. Doroshenko27, L.O’C. Drury4, J. Dyks32, K. Egberts33, G. Emery15, J.-P. Ernenwein19, S. Eschbach34, K. Feijen13, S. Fegan28, A. Fiasson23, G. Fontaine28, S. Funk34, M. Füßling35, S. Gabici29, Y.A. Gallant16, F. Gaté23, G. Giavitto35, D. Glawion24, J.F. Glicenstein17, D. Gottschall27, M.-H. Grondin25, J. Hahn3, M. Haupt35, G. Heinzelmann2, G. Henri30, G. Hermann3, J.A. Hinton3, W. Hofmann3, C. Hoischen33, T. L. Holch7, M. Holler12, D. Horns2, D. Huber12, H. Iwasaki39, M. Jamrozy36, D. Jankowsky34, F. Jankowsky24, I. Jung-Richardt34, M.A. Kastendieck2, K. Katarzynski´ 37, M. Katsuragawa40, U. Katz34, D. Khangulyan39, B. Khélifi29, J. King24, S. Klepser35, W. Klu´zniak32, Nu. Komin22, K. Kosack17, D. Kostunin35, M. Kraus34, G. Lamanna23, J. -

2015 Publication Year 2020-04-21T08:44:40Z Acceptance in OA@INAF Measuring Nickel Masses in Type Ia Supernovae Using Cobalt Emis

Publication Year 2015 Acceptance in OA@INAF 2020-04-21T08:44:40Z Title Measuring nickel masses in Type Ia supernovae using cobalt emission in nebular phase spectra Authors Childress, Michael J.; Hillier, D. John; Seitenzahl, Ivo; Sullivan, Mark; Maguire, Kate; et al. DOI 10.1093/mnras/stv2173 Handle http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12386/24142 Journal MONTHLY NOTICES OF THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY Number 454 Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 10 July 2015 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Measuring nickel masses in Type Ia supernovae using cobalt emission in nebular phase spectra Michael J. Childress1,2⋆, D. John Hillier3, Ivo Seitenzahl1,2, Mark Sullivan4, Kate Maguire5, Stefan Taubenberger5, Richard Scalzo1, Ashley Ruiter1,2, Nade- jda Blagorodnova7, Yssavo Camacho8,9, Jayden Castillo1, Nancy Elias-Rosa10, Morgan Fraser7, Avishay Gal-Yam11, Melissa Graham12, D. Andrew Howell13,14, Cosimo Inserra15, Saurabh W. Jha9, Sahana Kumar12, Paolo A. Mazzali16,17, Cur- tis McCully13,14, Antonia Morales-Garoffolo18, Viraj Pandya19,9, Joe Polshaw15, Brian Schmidt1, Stephen Smartt15, Ken W. Smith15, Jesper Sollerman20, Ja- son Spyromilio5, Brad Tucker1,2, Stefano Valenti13,14, Nicholas Walton7, Chris- tian Wolf1, Ofer Yaron11, D. R. Young15, Fang Yuan1,2, Bonnie Zhang1,2 1 Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia. 2ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO). 3Department of Physics and Astronomy & Pittsburgh Particle Physics, Astrophysics, and Cosmology Center (PITT PACC), University of Pittsburgh, 3941 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA. 4School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK. 5European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. -

Measuring Nickel Masses in Type Ia Supernovae Using Cobalt Emission in Nebular Phase Spectra

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 10 July 2015 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Measuring nickel masses in Type Ia supernovae using cobalt emission in nebular phase spectra Michael J. Childress1,2⋆, D. John Hillier3, Ivo Seitenzahl1,2, Mark Sullivan4, Kate Maguire5, Stefan Taubenberger5, Richard Scalzo1, Ashley Ruiter1,2, Nade- jda Blagorodnova7, Yssavo Camacho8,9, Jayden Castillo1, Nancy Elias-Rosa10, Morgan Fraser7, Avishay Gal-Yam11, Melissa Graham12, D. Andrew Howell13,14, Cosimo Inserra15, Saurabh W. Jha9, Sahana Kumar12, Paolo A. Mazzali16,17, Cur- tis McCully13,14, Antonia Morales-Garoffolo18, Viraj Pandya19,9, Joe Polshaw15, Brian Schmidt1, Stephen Smartt15, Ken W. Smith15, Jesper Sollerman20, Ja- son Spyromilio5, Brad Tucker1,2, Stefano Valenti13,14, Nicholas Walton7, Chris- tian Wolf1, Ofer Yaron11, D. R. Young15, Fang Yuan1,2, Bonnie Zhang1,2 1 Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia. 2ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO). 3Department of Physics and Astronomy & Pittsburgh Particle Physics, Astrophysics, and Cosmology Center (PITT PACC), University of Pittsburgh, 3941 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA. 4School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK. 5European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching b. M¨unchen, Germany. 7Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Rd., Cambridge, CB3 0HA, UK. 8Department of Physics, Lehigh University, 16 Memorial Drive East, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 18015, USA. 9Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 136 Frelinghuysen Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA. 10INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy. -

Hα Kinematics of S4G Spiral Galaxies - II

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1{?? (2015) Printed 27 April 2015 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Hα kinematics of S4G spiral galaxies - II. Data description and non-circular motions Santiago Erroz-Ferrer,1;2? Johan H. Knapen,1;2 Ryan Leaman,1;2;12 Mauricio Cisternas,1;2 Joan Font,1;2 John E. Beckman,1;2 Kartik Sheth,3 Juan Carlos Mu~noz-Mateos,4 Sim´onD´ıaz-Garc´ıa,5;6 Albert Bosma,7 E. Athanassoula,7 Bruce G. Elmegreen,8 Luis C. Ho,9;10 Taehyun Kim,3;4;9;11 Eija Laurikainen,5;6 Inma Martinez-Valpuesta,1;2 Sharon E. Meidt,12 and Heikki Salo5 1Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, V´ıaL´actea s/n 38205 La Laguna, Spain 2Departamento de Astrof´ısica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Spain 3National Radio Astronomy Observatory / NAASC, 520 Edgemont Road, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA 4European Southern Observatory, Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile 5Astronomy Division, Department of Physical Sciences, FIN-90014 University of Oulu, P.O. Box 3000, Oulu, Finland 6Finnish Centre of Astronomy with ESO (FINCA), University of Turku, V¨ais¨al¨antie20, FI-21500, Piikki¨o,Finland 7Aix Marseille Universit´eCNRS, LAM (Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille) UMR 7326, 13388, Marseille, France 8IBM Research Division, T.J. Watson Research Center, Yorktown Hts., NY 10598, USA 9The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA 10Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 11Astronomy Program, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Republic of Korea 12Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstronomie / K¨onigstuhl17 D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany Accepted 2015 April 23. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of

Draft version March 19, 2019 Typeset using LATEX modern style in AASTeX61 A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF SPITZER SUPERNOVAE Tamas´ Szalai,1,2 Szanna Zs´ıros,1 Ori D. Fox,3 Ondrejˇ Pejcha,4,5 and Tomas´ Muller¨ 6,7,8,9 1Department of Optics and Quantum Electronics, University of Szeged, H-6720 Szeged, D´om t´er 9., Hungary 2Konkoly Observatory, MTA CSFK, Konkoly-Thege M. ´ut 15-17, Budapest, 1121, Hungary 3Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 4Institute of Theoretical Physics, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic 5Lyman Spitzer Jr. Fellow, Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, 4 Ivy Lane, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA 6Millennium Institute of Astrophysics, Santiago, Chile 7Instituto de Astrof´ısica, Pontificia Universidad Cat´olica de Chile, Av. Vicu˜na Mackenna 4860, 782-0436 Macul, Santiago, Chile 8Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, Hampshire, SO17 1BJ, UK 9LSSTC Data Science Fellow (Received ...; Revised ...; Accepted ......) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT The mid-infrared (mid-IR) wavelength regime offers several advantages for following the late-time evolution of supernovae (SNe). First, the peaks of the SN spectral arXiv:1803.02571v2 [astro-ph.HE] 18 Mar 2019 energy distributions shift toward longer wavelengths following the photospheric phase. Second, mid-IR observations suffer less from effects of interstellar extinction. Third, and perhaps most important, the mid-IR traces dust formation and circumstellar interaction at late-times (>100 days) after the radioactive ejecta component fades. The Spitzer Space Telescope has provided substantial mid-IR observations of SNe since its launch in 2003. -

Comparative Internal Kinematics of the HII Regions in Interacting and Isolated Galaxies

MNRAS 451, 1307–1330 (2015) doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1024 Comparative internal kinematics of the H II regions in interacting and isolated galaxies: implications for massive star formation modes Javier Zaragoza-Cardiel,1,2‹ John E. Beckman,1,2,3 Joan Font,1,2 Begona˜ Garc´ıa-Lorenzo,1,2 Artemi Camps-Farina,˜ 1,2 Kambiz Fathi,4 Philip A. James,5 Santiago Erroz-Ferrer,1,2 Jorge Barrera-Ballesteros1,2 and Mauricio Cisternas1,2 1Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, C/ V´ıa Lactea´ s/n, E-38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 2Department of Astrophysics, University of La Laguna, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3CSIC, E-28006 Madrid, Spain 4Stockholm Observatory, Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, 146 Brownlow Hill, Liverpool L3 5RF, UK Downloaded from Accepted 2015 May 5. Received 2015 May 3; in original form 2014 November 14 http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ ABSTRACT We have observed 12 interacting galaxy pairs using the Fabry–Perot interferometer GH αFaS (Galaxy H α Fabry–Perot system) on the 4.2-m William Herschel Telescope at the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos, La Palma. We present here the Hα surface brightness, velocity and velocity dispersion maps for the 10 systems we have not previously observed using this technique, as well as the physical properties (sizes, Hα luminosities and velocity dispersion) of 1259 H II regions from the full sample. We also derive the physical properties of 1054 II H regions in a sample of 28 isolated galaxies observed with the same instrument in order at Liverpool John Moores University on August 11, 2015 to compare the two populations of H II regions. -

HB-NGC Index

Object Name Constellation Type Dec RA Season HB Page IC 1 Pegasus Double star +27 43 00 08.4 Fall C-21 IC 2 Cetus Galaxy -12 49 00 11.0 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 3 Pisces Galaxy -00 25 00 12.1 Fall C-39 IC 4 Pegasus Galaxy +17 29 00 13.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 5 Cetus Galaxy -09 33 00 17.4 Fall C-39 IC 6 Pisces Galaxy -03 16 00 19.0 Fall C-39 IC 8 Pisces Galaxy -03 13 00 19.1 Fall C-39 IC 9 Cetus Galaxy -14 07 00 19.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 10 Cassiopeia Galaxy +59 18 00 20.4 Fall C-03 IC 12 Pisces Galaxy -02 39 00 20.3 Fall C-39 IC 13 Pisces Galaxy +07 42 00 20.4 Fall C-39 IC 16 Cetus Galaxy -13 05 00 27.9 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 17 Cetus Galaxy +02 39 00 28.5 Fall C-39 IC 18 Cetus Galaxy -11 34 00 28.6 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 19 Cetus Galaxy -11 38 00 28.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 20 Cetus Galaxy -13 00 00 28.5 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 21 Cetus Galaxy -00 10 00 29.2 Fall C-39 IC 22 Cetus Galaxy -09 03 00 29.6 Fall C-39 IC 24 Andromeda Open star cluster +30 51 00 31.2 Fall C-21 IC 25 Cetus Galaxy -00 24 00 31.2 Fall C-39 IC 29 Cetus Galaxy -02 11 00 34.2 Fall C-39 IC 30 Cetus Galaxy -02 05 00 34.3 Fall C-39 IC 31 Pisces Galaxy +12 17 00 34.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 32 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.0 Fall C-39 IC 33 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.1 Fall C-39 IC 34 Pisces Galaxy +09 08 00 35.6 Fall C-39 IC 35 Pisces Galaxy +10 21 00 37.7 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 37 Cetus Galaxy -15 23 00 38.5 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 38 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 38.6 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 40 Cetus Galaxy +02 26 00 39.5 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 42 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 41.1 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC