A DEEP SEARCH for PROMPT RADIO EMISSION from THERMONUCLEAR SUPERNOVAE with the VERY LARGE ARRAY Laura Chomiuk1,11, Alicia M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE and GROUND-BASED OBSERVATIONS of the TYPE Iax SUPERNOVAE SN 2005Hk and SN 2008A

The Astrophysical Journal, 786:134 (19pp), 2014 May 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/786/2/134 C 2014. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE AND GROUND-BASED OBSERVATIONS OF THE TYPE Iax SUPERNOVAE SN 2005hk AND SN 2008A Curtis McCully1, Saurabh W. Jha1, Ryan J. Foley2,3, Ryan Chornock4, Jon A. Holtzman5, David D. Balam6, David Branch7, Alexei V. Filippenko8, Joshua Frieman9,10, Johan Fynbo11, Lluis Galbany12,13, Mohan Ganeshalingam8,14, Peter M. Garnavich15, Melissa L. Graham16,17,18,EricY.Hsiao18, Giorgos Leloudas11,19, Douglas C. Leonard20, Weidong Li8,29, Adam G. Riess21, Masao Sako22, Donald P. Schneider23, Jeffrey M. Silverman8,24,30, Jesper Sollerman11,25, Thea N. Steele8, Rollin C. Thomas26, J. Craig Wheeler24, and Chen Zheng27,28 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 136 Frelinghuysen Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; [email protected]. 2 Astronomy Department, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1002 West Green Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3 Department of Physics, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1110 West Green Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 4 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, MSC 4500, New Mexico State University, P.O. Box 30001, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA 6 Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 7 Homer L. Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA 8 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411, USA 9 Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics and Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 10 Center for Particle Astrophysics, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, P.O. -

Observational Studies of the Galaxy Peculiar Velocity Field

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES OF THE GALAXY PECULIAR VELOCITY FIELD by Philip Andrew James Astrophysics Group Blackett Laboratory Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine London SW7 2BZ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London and for the Diploma of Imperial College November 1988 1 ABSTRACT This thesis describes two observational studies of the peculiar velocity field of galaxies over scales of 50-100 Jr1 Mpc, and the consequences of these measurements for cosmological theories. An introduction is given to observational cosmology, emphasising the crucial questions of the nature of the dark matter and the formation of structure. The principal cosmological models are discussed, and the role of observations in developing these models is stressed. Consideration is given to those observations that are likely to prove good discriminators between the competing models, particular emphasis being given to studies of the coherent velocities of samples of galaxies. The first new study presented here uses optical photometry and redshifts, from the literature, for First Ranked Cluster Galaxies (FRCG’s). These galaxies are excellent standard candles, and thus ideal for peculiar velocity studies. A simple one dimensional analysis detects no relative motion between the Local Group of galaxies and 60 FRCG’s with redshifts of up to 15000 kms-1. This is shown to imply a streaming motion of the cluster galaxies of at least 600 kms_1 relative to the CBR. The second observational study is a reanalysis of the Rubin et al. (1976a,b) sample of Sc galaxies. Near-IR photometry is used in our reanalysis to minimise the effects of extinction and to facilitate the use of luminosity indicators in reducing the effects of selection biases. -

Pos(BASH 2013)009 † ∗ [email protected] Speaker

The Progenitor Systems and Explosion Mechanisms of Supernovae PoS(BASH 2013)009 Dan Milisavljevic∗ † Harvard University E-mail: [email protected] Supernovae are among the most powerful explosions in the universe. They affect the energy balance, global structure, and chemical make-up of galaxies, they produce neutron stars, black holes, and some gamma-ray bursts, and they have been used as cosmological yardsticks to detect the accelerating expansion of the universe. Fundamental properties of these cosmic engines, however, remain uncertain. In this review we discuss the progress made over the last two decades in understanding supernova progenitor systems and explosion mechanisms. We also comment on anticipated future directions of research and highlight alternative methods of investigation using young supernova remnants. Frank N. Bash Symposium 2013: New Horizons in Astronomy October 6-8, 2013 Austin, Texas ∗Speaker. †Many thanks to R. Fesen, A. Soderberg, R. Margutti, J. Parrent, and L. Mason for helpful discussions and support during the preparation of this manuscript. c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. http://pos.sissa.it/ Supernova Progenitor Systems and Explosion Mechanisms Dan Milisavljevic PoS(BASH 2013)009 Figure 1: Left: Hubble Space Telescope image of the Crab Nebula as observed in the optical. This is the remnant of the original explosion of SN 1054. Credit: NASA/ESA/J.Hester/A.Loll. Right: Multi- wavelength composite image of Tycho’s supernova remnant. This is associated with the explosion of SN 1572. Credit NASA/CXC/SAO (X-ray); NASA/JPL-Caltech (Infrared); MPIA/Calar Alto/Krause et al. -

![Arxiv:1402.6337V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 25 Feb 2014 Novae (SN Ia) Prevent Studies from Conclusively Singling Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2181/arxiv-1402-6337v1-astro-ph-he-25-feb-2014-novae-sn-ia-prevent-studies-from-conclusively-singling-et-al-282181.webp)

Arxiv:1402.6337V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 25 Feb 2014 Novae (SN Ia) Prevent Studies from Conclusively Singling Et Al

A review of type Ia supernova spectra J. Parrent1,2, B. Friesen3, and M. Parthasarathy4 Abstract SN 2011fe was the nearest and best-observed fairly certain that the progenitor system of SN Ia com- type Ia supernova in a generation, and brought previ- prises at least one compact C+O white dwarf (Chan- ous incomplete datasets into sharp contrast with the drasekhar 1957; Nugent et al. 2011; Bloom et al. 2012). detailed new data. In retrospect, documenting spectro- However, how the state of this primary star reaches scopic behaviors of type Ia supernovae has been more a critical point of disruption continues to elude as- often limited by sparse and incomplete temporal sam- tronomers. This is particularly so given that less than pling than by consequences of signal-to-noise ratios, ∼ 15% of locally observed white dwarfs have a mass a telluric features, or small sample sizes. As a result, few 0.1M greater than a solar mass; very few systems 5 type Ia supernovae have been primarily studied insofar near the formal Chandrasekhar-mass limit ,MCh ≈ as parameters discretized by relative epochs and incom- 1.38 M (Vennes 1999; Liebert et al. 2005; Napiwotzki plete temporal snapshots near maximum light. Here we et al. 2005; Parthasarathy et al. 2007; Napiwotzki et al. discuss a necessary next step toward consistently mod- 2007). eling and directly measuring spectroscopic observables Thus far observational constraints of SN Ia have of type Ia supernova spectra. In addition, we analyze been inconclusive in distinguishing between the follow- current spectroscopic data in the parameter space de- ing three separate theoretical considerations about pos- fined by empirical metrics, which will be relevant even sible progenitor scenarios. -

CFAIR2: NEAR INFRARED LIGHT CURVES of 94 TYPE IA SUPERNOVAE Andrew S

submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Supplements Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 05/12/14 CFAIR2: NEAR INFRARED LIGHT CURVES OF 94 TYPE IA SUPERNOVAE Andrew S. Friedman1,2, W. M. Wood-Vasey3, G. H. Marion1,4, Peter Challis1, Kaisey S. Mandel1, Joshua S. Bloom5, Maryam Modjaz6, Gautham Narayan1,7,8, Malcolm Hicken1, Ryan J. Foley9,10, Christopher R. Klein5, Dan L. Starr5, Adam Morgan5, Armin Rest11, Cullen H. Blake12, Adam A. Miller13, Emilio E. Falco1, William F. Wyatt1, Jessica Mink1, Michael F. Skrutskie14, and Robert P. Kirshner1 (Dated: July 23, 2018) submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Supplements ABSTRACT CfAIR2 is a large homogeneously reduced set of near-infrared (NIR) light curves for Type Ia super- novae (SN Ia) obtained with the 1.3m Peters Automated InfraRed Imaging TELescope (PAIRITEL). This data set includes 4637 measurements of 94 SN Ia and 4 additional SN Iax observed from 2005- 2011 at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona. CfAIR2 includes JHKs photometric measurements for 88 normal and 6 spectroscopically peculiar SN Ia in the nearby uni- verse, with a median redshift of z ∼ 0:021 for the normal SN Ia. CfAIR2 data span the range from -13 days to +127 days from B-band maximum. More than half of the light curves begin before the time of maximum and the coverage typically contains ∼ 13{18 epochs of observation, depending on the filter. We present extensive tests that verify the fidelity of the CfAIR2 data pipeline, including comparison to the excellent data of the Carnegie Supernova Project. CfAIR2 contributes to a firm local anchor for supernova cosmology studies in the NIR. -

Luminous Blue Variables: an Imaging Perspective on Their Binarity and Near Environment?,??

A&A 587, A115 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526578 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics Luminous blue variables: An imaging perspective on their binarity and near environment?;?? Christophe Martayan1, Alex Lobel2, Dietrich Baade3, Andrea Mehner1, Thomas Rivinius1, Henri M. J. Boffin1, Julien Girard1, Dimitri Mawet4, Guillaume Montagnier5, Ronny Blomme2, Pierre Kervella7;6, Hugues Sana8, Stanislav Štefl???;9, Juan Zorec10, Sylvestre Lacour6, Jean-Baptiste Le Bouquin11, Fabrice Martins12, Antoine Mérand1, Fabien Patru11, Fernando Selman1, and Yves Frémat2 1 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Alonso de Córdova 3107, Vitacura, 19001 Casilla, Santiago de Chile, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 Royal Observatory of Belgium, 3 avenue Circulaire, 1180 Brussels, Belgium 3 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching b. München, Germany 4 Department of Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5 Observatoire de Haute-Provence, CNRS/OAMP, 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France 6 LESIA (UMR 8109), Observatoire de Paris, PSL, CNRS, UPMC, Univ. Paris-Diderot, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France 7 Unidad Mixta Internacional Franco-Chilena de Astronomía (CNRS UMI 3386), Departamento de Astronomía, Universidad de Chile, Camino El Observatorio 1515, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 8 ESA/Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, -

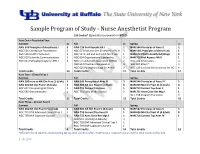

Sample Program of Study

Sample Program of Study - Nurse Anesthetist Program 126 Credits* (Specialty coursework in BOLD) Year One – Preclinical Year Summer Cr Fall Cr Spring Cr NAN 543 Principles of Anesthesia I 3 NAN 718 Prof Aspects NA I 1 NAN 544 Principles of Anes II 2 NGC 501 Conceptual Foundations 3 NGC 527 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC II 3 NAN 544L Principles of Anes II Lab 1 NGC 518 Health Promotion 3 NGC 527L Eval and Gen Evidence II Lab 1 NAN 672 Pharm Anesth/Adj Drugs 3 NGC 520 Scientific Communications 2 NGC 634 Organizational Leadership 3 NAN 719 Prof Aspects NA II 1 NGC 625 Pathophysiology for APN I 3 NGC 575 Adv Helth Assessmnt (CRNA) 2 NGC 502 Informatics 3 NGC 612 Pharmacotherapeutics 4 NGC 509 Ethics* 3 NGC 626 Pathophysiology for APN II 3 NGC 526 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC I 4 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 17 Total Credits 17 Year Two – Clinical Year I Summer Fall Spring NAN 598 Intro to NA Clin Prac (1 d/wk) 2 NAN 545 Principles of Anes III 3 NAN 546 Principles of Anes IV 3 NAN 601 NA Clin Pract I (3 d/wk) 6 NAN 602 NA Clin Pract II (4 d/wk) 8 NAN 603 NA Clin Pract III (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 632 Interpreting HC Policy 3 NAN 711 Current Top Anes 1 NAN 712 Current Top Anes II 1 NGC 692 Grantsmanship 1 NGC 701 State of the Science 3 NAN 721 Anes Crisis Res Mgt I 1 NGC 638 Program Evaluation 3 Total Credits 12 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 16 Year Three – Clinical Year II Summer Fall Spring NAN 604 NA Clin Pract IV (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 605 NA Clin Pract V (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 547 Principles of Anes V 3 NGC 725 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac I 2 NAN 713 Current Top Anes III 1 NAN 606 NA Clin Pract VI (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 798 DNP Capstone Course I 1 NAN 722 Anes Crisis Res Mgt II 1 NAN 714 Current Top Anes IV 1 NGC 533 Teaching in Nursing 3 NGC 726 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac II 2 NGC 799 DNP Capstone Course II 1 Total Credits 9 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 12 *Effective for all students matriculating Spring 2015 and thereafter, N509 is not a required course and the total credits will be 123. -

Supernovae in Dense and Dusty Environments

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA - SER. A I OSA - TOM. 456 ASTRONOMICA - CHEMICA - PHYSICA - MATHEMATICA SUPERNOVAE IN DENSE AND DUSTY ENVIRONMENTS by Erkki Kankare TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2013 From Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Turku FI-20014 Turku Finland Supervised by Dr. Seppo Mattila Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Turku Finland Reviewed by Prof. Juri Poutanen Dr. Dovi Poznanski Astronomy Division School of Physics and Astronomy Department of Physics Tel Aviv University University of Oulu Israel Finland Opponent Dr. Bruno Leibundgut European Southern Observatory Germany ISBN 978-951-29-5291-5 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-5292-2 (PDF) ISSN 0082-7002 Painosalama Oy - Turku, Finland 2013 Acknowledgements First of all a big thank you to my supervisor Seppo Mattila who introduced me to supernovae and relentlessly guided me through my long PhD process and never stopped listening to his student who so often walked into his office to bother him. Many thanks too to my MSc supervisor Pekka Teerikorpi who intro- duced me into making science in the first place. I would also like to thank Stuart Ryder for the very successful collaboration on the Gemini programme, and Stefano Benetti for including me in the ESO/NTT Large Programme. Similar thanks go to Rubina Kotak, Peter Lundqvist, Andrea Pastorello, Miguel Angel´ P´erez-Torres, Cristina Romero-Ca˜nizales, Jason Spyromilio, Stefano Valenti, Petri V¨ais¨anen and all the other colleagues with whom I have had the honour to work, but who are unfortunately far too many to name here. -

A Second Case of Variable Na ID Lines in a Highly-Reddened Type

Accepted for publication in ApJ A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 ERRATUM: “A SECOND CASE OF VARIABLE Na I D LINES IN A HIGHLY-REDDENED TYPE Ia SUPERNOVA” (2009, ApJ, 693, 207) Stephane´ Blondin,1,2,* Jose´ L. Prieto,3,† Ferdinando Patat,2 Peter Challis,1 Malcolm Hicken,1 Robert P. Kirshner,1,‡ Thomas Matheson,4 Maryam Modjaz5,§ 1. NO VARIABLE Na I D LINES IN SN 1999cl of SN 1999cl in a spiral arm with a blueshifted velocity The large variation in the Na I D equivalent width along the line of sight, as derived from kinematic maps (EW) observed in the Type Ia SN 1999cl (Blondin et al. of NGC 4501 based on H I emission by Chemin et al. ± ˚ (2006). We note that Garnavich et al. (1999) had in fact 2009), ∆EW = 1.66 0.21 A, results in fact from a mea- correctly reported a Na I D EW of 0.33nm for their first surement error. The origin of this error was traced back spectrum of SN 1999cl, consistent with our revised mea- I to observed wavelength shifts of the Na D profile with surement on the same spectrum. respect to its expected restframe location (5889.95 and All the other objects in our sample display significantly ˚ 5895.92 A for the D2 and D1 lines, respectively), which lower wavelength shifts of the Na I D profile (. 4 A˚ in were not properly taken into account in a revised im- absolute value; see Fig. 2). We have not investigated plementation of our EW computation (albeit correctly the exact nature of the observed wavelength shifts for displayed on the graphical interface developed for these all the objects in our sample, but simply note that ab- measurements; see Fig. -

Luminous Blue Variables: an Imaging Perspective on Their Binarity and Near Environment

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. article12LBVn5 c ESO 2016 January 15, 2016 Luminous blue variables: An imaging perspective on their binarity and near environment? Christophe Martayan1, Alex Lobel2, Dietrich Baade3, Andrea Mehner1, Thomas Rivinius1, Henri M. J. Boffin1, Julien Girard1, Dimitri Mawet4, Guillaume Montagnier5, Ronny Blomme2, Pierre Kervella6; 7, Hugues Sana8, Stanislav Štefl??9, Juan Zorec10, Sylvestre Lacour6, Jean-Baptiste Le Bouquin11, Fabrice Martins12, Antoine Mérand1, Fabien Patru11, Fernando Selman1, and Yves Frémat2 1 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Alonso de Córdova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Santiago de Chile, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 Royal Observatory of Belgium, 3 Avenue Circulaire, 1180 Brussels, Belgium 3 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching b. München, Germany 4 Department of Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA 5 Observatoire de Haute-Provence, CNRS/OAMP, 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France 6 LESIA, UMR 8109, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC, Univ. Paris-Diderot, PSL, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France 7 Unidad Mixta Internacional Franco-Chilena de Astronomía (UMI 3386), CNRS/INSU, France & Departamento de Astronomía, Universidad de Chile, Camino El Observatorio 1515, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 8 ESA / Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39