Uzbekistan by Bruce Pannier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Responsibilities in Combating Trafficking in Persons in Central Asia, 27 Loy

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 27 Number 2 Article 1 3-1-2005 State Responsibilities in Combating Trafficking inersons P in Central Asia Mohamed Y. Mattar Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mohamed Y. Mattar, State Responsibilities in Combating Trafficking in Persons in Central Asia, 27 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 145 (2005). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol27/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. State Responsibilities in Combating Trafficking in Persons in Central Asia MOHAMED Y. MATAR* I. INTRODUCTION Since the early 1990s, trafficking in persons has been among the major human rights problems in the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe. In more recent years, however, "the focus of human traffickers ha[s] shifted to... Central Asia, a region fraught with social, political, and economic tension."' Existing research on the issue suggests that the fastest growth rates of trafficking are currently observed in the former Soviet Union, including Central Asia,2 and estimates that the region "is becoming the most important geographical source of trafficking in women in Asia."3 Further, trafficking in persons is a significant problem in the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, * Mohamed Y. -

RUSSIA and CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI

RUSSIA AND CHINA. ANATOMY OF A A PARTNERSHIP OF AND RUSSIA CHINA. ANATOMY Aldo Ferrari While the “decline of the West” is now almost taken is Head of the Russia, Caucasus for granted, China’s impressive economic performance RUSSIA AND CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI. and the political influence of an assertive Russia in the international arena are combining to make Eurasia a key Founded in 1934, ISPI is Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti Anatomy of a Partnership hub of political and economic power. That, certainly, an independent think tank is a Research Fellow committed to the study of is the story which Beijing and Moscow have been telling at the Russia, Caucasus and international political and Central Asia Centre at ISPI. for years. edited by Aldo Ferrari and Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti economic dynamics. Are the times ripe for a “Eurasian world order”? What It is the only Italian Institute exactly does the supposed Sino-Russian challenge to introduction by Paolo Magri – and one of the very few in the liberal world entail? Are the two countries’ worsening Europe – to combine research clashes with the West drawing them closer together? activities with a significant This ISPI Report tackles every aspect of the apparently commitment to training, events, solidifying alliance between Moscow and Beijing, but also and global risk analysis for points out its growing asymmetries. It also recommends companies and institutions. some policies that could help the EU to deal with this ISPI favours an interdisciplinary “Eurasian shift”, a long-term and multi-faceted power and policy-oriented approach made possible by a research readjustment that may lead to the end of the world team of over 50 analysts and as we have known it. -

Russia's Foreign Policy: Key Regions and Issues

Forschungsstelle Osteuropa Bremen Arbeitspapiere und Materialien No. 87 – November 2007 Russia's Foreign Policy: Key Regions and Issues Edited by Robert Orttung, Jeronim Perovic, Heiko Pleines, Hans-Henning Schröder Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen Klagenfurter Straße 3, D-28359 Bremen Tel. +49 421 218-3687, Fax +49 421 218-3269 http://www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Arbeitspapiere und Materialien – Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen Working Papers of the Research Centre for East European Studies, Bremen No. 87: Robert Orttung, Jeronim Perovic, Heiko Pleines, Hans-Henning Schröder (eds.): Russia’s Foreign Policy: Key Regions and Issues November 2007 ISSN: 1616-7384 All contributions in this Working Paper are reprints from the Russian Analytical Digest. About the Russian Analytical Digest: The Russian Analytical Digest is a bi-weekly internet publication which is jointly produced by the Research Centre for East European Studies [Forschungsstelle Osteuropa] at the University of Bremen (www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de) and the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich) (www.css.ethz.ch). It is supported by the Otto-Wolff-Foundation and the German Association for East European Studies (DGO). The Digest draws from contributions to the German-language Russlandanalysen, the CSS analytical network Russian and Eurasian Security Network (RES) and the Russian Regional Report. For a free subscription and for back issues please visit the Russian Analytical Digest website at www.res.ethz.ch/analysis/rad Technical Editor: Matthias Neumann Cover based on a work of art by Nicholas Bodde Opinions expressed in publications of the Research Centre for East European Studies are solely those of the authors. -

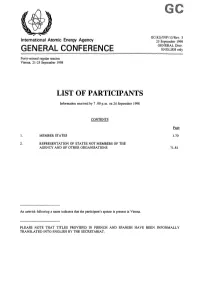

List of Participants

GC(42)/INF/13/Rev. 3 International Atomic Energy Agency 25 September 1998 GENERAL Distr. GENERAL CONFERENCE ENGLISH only Forty-second regular session Vienna, 21-25 September 1998 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Information received by 7 .00 p.m. on 24 September 1998 CONTENTS 1. MEMBER STATES 1-70 2. REPRESENTATION OF STATES NOT MEMBERS OF THE AGENCY AND OF OTHER ORGANISATIONS 71-81 An asterisk following a name indicates that the participant's spouse is present in Vienna. PLEASE NOTE THAT TITLES PROVIDED IN FRENCH AND SPANISH HAVE BEEN INFORMALLY TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY THE SECRETARIAT. 1. MEMBER STATES AFGHANISTAN Delegate: Mr. Farid A. AMIN Acting Resident Representative to the Agency ALBANIA Delegate: Mr. Spiro KOÇI First Secretary Alternate to the Resident Representative Alternate: Mr. Robert KUSHE Director Institute of Nuclear Physics, Tirana ALGERIA Delegate: Mr. Abderrahmane KADRİ Chairman, Atomic Energy Commission Head of the Delegation Advisers: Mr. Mokhtar REGUIEG Ambassador to Austria Resident Representative to the Agency Mr. El Arbi ALIOUA Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Mohamed CHIKOUCHE Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Salah DJEFFAL Director Center for Radiation Protection and Security (CRS) Mr. YoussefTOUIL Director Center for Development of Nuclear Technologies (CDTN) Mr. Ali AISSAOUI Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Abdelmadjid DRAIA Counsellor Permanent Mission in Vienna Mr. Boualem CHEBIHI Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs ARGENTINA Delegate: Mr. Juan Carlos KRECKLER Ambassador to Austria Designated Resident Representative to the Agency Alternates: Mr. Dan BENINSON President of the Board Nuclear Regulatory Authority (ARN) Alternate to the Governor Mr. Pedro VILLAGRA DELGADO Director, International Security Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship Alternate to the Governor Mr. -

Kazakh President Addresses Global Issues in Astana Club Speech AIFC, Green Tech Centre and IT Start-Up Hub to Begin Operating

0° / -6°C WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2017 No 22 (136) www.astanatimes.com Kazakh President addresses global Nazarbayev, Putin discuss issues in Astana Club speech developing human capital at interregional forum “Experts forecast that by 2030, By Aigerim Seisembayeva about 60 professions in various spheres will vanish, and more than ASTANA – A number of inter- 180 new ones will emerge. Accord- state, intergovernmental, regional ing to the Human Development and commercial documents were Report, in the next five years, more signed Nov. 9 at the 14th Forum of than a third of knowledge and skills Interregional Cooperation between necessary for work will change. Kazakhstan and Russia in Chely- This is a serious challenge, and its abinsk. Visiting Kazakh President solution should become one of our Nursultan Nazarbayev and his cooperation’s top priorities,” he Russian counterpart Vladimir Pu- said, adding that it is important to tin also signed a joint statement develop human capital in educa- devoted to the 25th anniversary of tion, health and social protection. diplomatic relations between the “To date, more than 30 Ka- two states (Oct. 22, 1992). zakh universities conduct joint “Our interregional cooperation is scientific research with Russian the basis of economic interaction, universities. I propose to create President Nursultan Nazarbayev (C) speaks to the politicians and experts in Astana on Nov. 13, flanked by Parliament Senate Chairman Kassym-Jomart Tokayev (L) and Institute of World Economy and Politics Director Yerzhan Saltybayev. which, despite all the difficulties, is Kazakh-Russian scientific con- growing. In the past nine months, our sortiums in promising areas, such trade turnover grew 31 percent. -

Osce Conflict Management in Central Asia Fighting Windmills Like Don Quixote

security and human rights 27 (2016) 479-497 brill.com/shrs osce Conflict Management in Central Asia Fighting Windmills like Don Quixote Pál Dunay Professor of nato and European Security Issues, George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany Abstract Conflicts and their management in Central Asia have never been prioritised by the osce although five states of the region are among its participating states. This has been due to that unlike in some other parts of the post-Soviet space most of the con- flicts did not threaten with military escalation, and the intensity of strategic rivalry is less noticeable in this distant part of the osce area than closer to the heart of E urope. The fact Russia is not a direct party to the conflicts in Central Asia also reduces the interests of many participating states. There was one high intensity conflict in the re- gion, the Tajik civil war that came too early for the osce. Lower intensity conflicts, ranging from border skirmishes, disputes about access to water, violation of rights of national minority groups, rigged elections are monitored and their resolutions are fa- cilitated by the organisation. Some of them, like the 2010 Kyrgyz-Uzbek conflict had such short shelf-life internationally that no consensus-based inter-governmental organisation could have effectively intervened into it. The osce has been successful in conflict management when the party or parties also wanted to break the stale-mate that the Organization could facilitate. Domestic change in some Central Asian states is essential for advancing the osces cooperative security approach. -

Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests

Order Code RS21238 Updated August 27, 2008 Uzbekistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Uzbekistan is a potential Central Asian regional power by virtue of its relatively large population, energy and other resources, and location in the heart of the region. It has failed to make progress in economic and political reforms, and many observers criticize its human rights record. This report discusses U.S. policy and assistance. Basic facts and biographical information are provided. This report may be updated. Related products include CRS Report RL33458, Central Asia: Regional Developments and Implications for U.S. Interests. U.S. Policy According to the Administration, “it is in the U.S. and Uzbekistan’s interest to promote democracy, respect for human rights, territorial integrity, and the transition to a market-based economy in order to bolster greater social and political stability.” However, the Uzbek government’s continued “repression of civil society, religious groups, and political opposition [decreases] options for U.S. assistance.”1 Cumulative U.S. assistance budgeted for Uzbekistan in FY1992-FY2007 was $845.5 million (FREEDOM Support Act and agency budgets). In FY2008, estimated budgeted assistance was $10.19 million, and the Administration has requested $7.94 million for FY2009 (FREEDOM Support Act and other Function 150 foreign aid, excluding Defense and Energy Department funds). The main priorities of U.S. assistance requested for FY2009 are planned to be democratization, healthcare, and agricultural reforms. Plans for FY2009 include support for local groups, lawyers, and 1 U.S. -

5 December 2008 HELSINKI

MC.INF/13/08/Rev.5 5 December 2008 ENGLISH only FINAL List of Participants for the 16th OSCE Ministerial Council Meeting 4 - 5 December 2008 HELSINKI 1 ALBANIA Mr. Lulzim BASHA Minister of Foreign Affairs Head of Delegation Mr. Gilbert GALANXHI Ambassador, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Albania to the OSCE Mr. Spiro KOCI General Director, Euro-Atlantic Integration and Multilateral Relations, Ministry for Foreign Affairs Mr. Xhodi SAKIQI Head of OSCE and CoE Section, Ministry¨ of Foreign Affairs Mr. Entela GJIKA First Secretary, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Albania to the OSCE GERMANY Dr. Frank-Walter STEINMEIER Federal Foreign Minister, Head of Delegation Mr. Heiner HORSTEN Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Mr. Klaus-Peter GOTTWALD Federal Government Commissioner for Disarmament and Arms Control, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Mr. Eberhard POHL Deputy Political Director at the Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Mr. Cyrill Jean NUNN Deputy Head of the Federal Foreign Ministers´ Office Mr. Gerhard KÜNTZLE Minister, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Mr. Wolfgang RICHTER Colonel, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Mr. Michael BIONTINO First Counsellor, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Ms. Margit HELLWIG-BÖTTE First Counsellor, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Ms. Perry Andrea NOTBOHM-RUH Interpreter, Federal Foreign Office, Berlin 2 Mr. Jens-Uwe PLÖTNER Spokesperson of the Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Mr. Walter SCHWEIZER Colonel, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Mr. Hans-Joachim RATZLAFF Colonel, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Mr. Bernd PFAFFENBACH Lieutenant Colonel, Ministry of Defence, Berlin Mr. Jan KANTORCZYK Counsellor, Permanent Mission of Germany to the OSCE Ms. -

List of Participants

INTERNATIONAL AFGHANISTAN CONFERENCE LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Chair Host Afghanistan Germany H.E. Mr. Hamed Karzai H.E. Dr. Guido Westerwelle President Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs and H.E. Dr. Zalmai Rassoul Minister of Foreign Affairs PARTICIPANTS (in alphabetical order) Albania Belgium Cyprus H.E. Mr. Edmond Haxhinasto H.E. Mr. Jean-Arthur Regibeau H.E. Mr. Pantias D. Eliades Deputy Prime Minister and Director General for Political Ambassador* Minister of Foreign Affairs Affairs Czech Republic Algeria Bosnia and Herzegovina H.E. Mr. Karel Schwarzenberg H.E. Mr. Madjid Bouguerra H.E. Mr. Sven Alkalaj First Deputy Prime Minister and Ambassador* Minister of Foreign Affairs Minister of Foreign Affairs Argentina Brazil Denmark H.E. Mr. Victorio Taccetti H.E. Mr. Everton Vieira Vargas H.E. Mr. Villy Søvndal Ambassador* Ambassador* Minister for Foreign Affairs Armenia Brunei Egypt H.E. Mr. Edward Nalbandian H.E. Mr. Pehin Mohammad H.E. Ambassador Wafaa Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusof Abu Bakar Bassim Ambassador* Assistant Minister of Australia Foreign Affairs H.E. Mr. Kevin Rudd Bulgaria Minister for Foreign Affairs H.E. Mr. Nickolay Mladenov El Salvador Minister of Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Anita Cristina Escher Austria Echeverría H.E. Dr. Johannes Kyrle Canada Ambassador* Secretary-General for Foreign H.E. Mr. John Baird Affairs Minister of Foreign Affairs Estonia H.E. Mr. Urmas Paet Azerbaijan China Minister of Foreign Affairs H.E. Mr. Elmar Mammadyarov H.E. Mr. Yang Jiechi Minister of Foreign Affairs Minister of Foreign Affairs Finland H.E. Mr. Erkki Tuomioja Bahrain Colombia Minister for Foreign Affairs H.E. -

Nations in Transit 2015 Executive Summary

Uzbekistan by Sarah Kendzior Capital: Tashkent Population: 30.7 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$5,840 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators 2015. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Electoral Process 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Independent Media 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 National Democratic Governance 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Local Democratic Governance 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Corruption 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Democracy Score 6.82 6.82 6.86 6.89 6.93 6.93 6.93 6.93 6.93 6.93 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

RUSSIA and CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI

RUSSIA AND CHINA. ANATOMY OF A A PARTNERSHIP OF AND RUSSIA CHINA. ANATOMY Aldo Ferrari While the “decline of the West” is now almost taken is Head of the Russia, Caucasus for granted, China’s impressive economic performance RUSSIA AND CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI. and the political influence of an assertive Russia in the international arena are combining to make Eurasia a key Founded in 1934, ISPI is Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti Anatomy of a Partnership hub of political and economic power. That, certainly, an independent think tank is a Research Fellow committed to the study of is the story which Beijing and Moscow have been telling at the Russia, Caucasus and international political and Central Asia Centre at ISPI. for years. edited by Aldo Ferrari and Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti economic dynamics. Are the times ripe for a “Eurasian world order”? What It is the only Italian Institute exactly does the supposed Sino-Russian challenge to introduction by Paolo Magri – and one of the very few in the liberal world entail? Are the two countries’ worsening Europe – to combine research clashes with the West drawing them closer together? activities with a significant This ISPI Report tackles every aspect of the apparently commitment to training, events, solidifying alliance between Moscow and Beijing, but also and global risk analysis for points out its growing asymmetries. It also recommends companies and institutions. some policies that could help the EU to deal with this ISPI favours an interdisciplinary “Eurasian shift”, a long-term and multi-faceted power and policy-oriented approach made possible by a research readjustment that may lead to the end of the world team of over 50 analysts and as we have known it. -

Russia and China's Quiet Rivalry in Central Asia

CENTRAL ASIA INITIATIVE R C’ Q R C A N Y All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Niva Yau The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy- oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities. Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Editing: Thomas J. Shattuck Design: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute September 2020 OUR MISSION The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. We educate those who make and influence policy, as well as the public at large, through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S.