THIRD PRESENTATION of the CHARLES LANG FREER MEDAL September 15, 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SORS-2021-1.2.Pdf

Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC The Smithsonian Opportunities for Research and Study Guide Can be Found Online at http://www.smithsonianofi.com/sors-introduction/ Version 1.1 (Updated August 2020) Copyright © 2021 by Smithsonian Institution Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 How to Use This Book .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Archives of American Art (AAA) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (CHNDM) ............................................................................................................................. -

Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery of Art : Turn-Of-The-Century Politics and Aesthetics on the National Mall

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2007 Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall. Patricia L. Guardiola University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guardiola, Patricia L., "Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 543. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/543 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2007 CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Approved on June 8, 2007 By the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION In memory of my grandfathers, Mr. -

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery/Freer Gallery of Art

ARTHUR M. SACKLER GALLERY/FREER GALLERY OF ART APPLICATION OF OPERATING RESOURCES FEDERAL GENERAL DONOR/SPONSOR- GOV’T GRANTS APPROPRIATIONS TRUST DESIGNATED & CONTRACTS FTE $000 FTE $000 FTE $000 FTE $000 FY 2007 48 5,679 0 0 57 10,543 0 0 ACTUAL FY 2008 57 5,787 0 434 65 12,480 0 0 ESTIMATE FY 2009 57 5,937 0 434 65 12,480 0 0 ESTIMATE STRATEGIC GOALS: INCREASED PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT; STRENGTHENED RESEARCH; AND ENHANCED MANAGEMENT EXCELLENCE Federal Resource Summary by Performance Objective and Program Category Performance Objective/ FY 2008 FY 2009 Change Performance Category FTE $000 FTE $000 FTE $000 Increased Public Engagement Public Programs Engage and inspire diverse audiences 8 812 8 834 0 22 Provide reference services and information to the 8 812 8 833 0 21 public Exhibitions Offer compelling, first-class exhibitions 15 1,523 15 1,562 0 39 Collections Improve the stewardship of the national 14 1,421 14 1,458 0 37 collections Strengthened Research Research Ensure the advancement of knowledge in the 4 406 4 417 0 11 humanities Enhanced Management Excellence Information Technology Modernize the Institution’s information technology 3 305 3 312 0 7 systems and infrastructure Management Operations Modernize the Institution’s financial management 5 508 5 521 0 13 and accounting operations Total 57 5,787 57 5,937 0 150 77 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (FSG) celebrate the artistic traditions of Asia and are widely regarded as one of the world’s most important centers for collections of Asian art. -

Freer Sackler Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet Freer|Sackler Smithsonian Institution ABOUT THE FREER|SACKLER The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, located on the National Mall in Washington, DC, comprise the Smithsonian’s museum of Asian art. The Freer|Sackler contains one of the most important collections of Asian art in the world, featuring more than 40,000 objects dating from the Neolithic period to the present day, with especially fine groupings of Islamic art; Chinese jades, bronzes, and paintings; and the art of the ancient Near East. The museum also contains important masterworks from Japan, ancient Egypt, South and Southeast Asia, and Korea, as well as a noted collection of American art. The Freer|Sackler is committed to expanding public knowledge of the collections through exhibitions, research, and publications. As of 2016, the Freer building is closed for renovation. It will reopen in 2017 with modernized technology and infrastructure, refreshed gallery spaces, and an enhanced Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Auditorium. Visit asia.si.edu/future for more information. BACKGROUND AND COLLECTIONS Charles Lang Freer, a self-taught connoisseur, began purchasing American art in the 1880s. With the encouragement of American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Freer also began to collect Asian art, assembling a preeminent group of works. In 1904, Freer offered his collection to the nation, to be held in trust by the Smithsonian Institution. The Freer Gallery of Art opened to the public in 1923—the first Smithsonian museum dedicated to fine art. The Freer’s collection spans six thousand years and many different cultures. Besides Asian art, the Freer houses a collection of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art, including the world’s largest number of works by Whistler. -

The Smithsonian Comprehensive Campaign

1002435_Smithsonian.qxp:Layout 1 6/29/10 10:03 AM Page 1 JUNE 2010 briefing paper for the smithsonian comprehensive campaign Smithsonian Institution 1002435_Smithsonian.qxp:Layout 1 6/29/10 10:03 AM Page 2 SMITHSONIAN CAMPAIGN BRIEFING PAPER Smithsonian Institution at a Glance MUSEUMS Anacostia Community Museum Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden National Air and Space Museum and Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center National Museum of African American History and Culture National Museum of African Art National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center National Museum of the American Indian and the George Gustav Heye Center National Museum of Natural History National Portrait Gallery National Postal Museum National Zoological Park Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery RESEARCH CENTERS Archives of American Art Museum Conservation Institute Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Smithsonian Environmental Research Center Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Libraries Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (Panama) EDUCATION AND OUTREACH Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage National Science Resources Center Office of Fellowships Smithsonian Affiliations Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program Smithsonian Center for Education and Museum Studies Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service Smithsonian Latino Center The Smithsonian Associates 1002435_Smithsonian.qxp:Layout 1 6/29/10 10:03 AM Page 1 SMITHSONIAN CAMPAIGN BRIEFING PAPER The Smithsonian Stands in Singular Space WE ARE KEEPERS OF THE AMERICAN SPIRIT and stewards of our sacred objects. We speak with voices that reflect our diversity and tell the stories that define our common experience. -

The Oscartek Journal

___________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 102 May 2021 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ New U.S refrigerant The Journal mandate; read below Smithsonian Museum reopens to visitors; Vibrant History is coming alive ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CHANTILLY, Va. May 1, 2021 — The Smithsonian reopened the first of several museums on Wednesday after closing because of the COVID-19 crisis. A bit of bright news for the Washington, D.C., cultural scene (and tourism machine): A slew of Smithsonian Institution-operated museums—seven in total—along with the National Zoo will reopen throughout May after being shuttered for over a year, save for a brief phased reopening last summer and fall. The sweeping closures were instituted as part of a second District-wide rollout of COVID-19 shutdowns in November put in place as a new wave of infections swept the nation. With the Smithsonian being a notable holdout, many smaller private museums across the nation’s capital, and the country, have already The Smithsonian, Maryland Ave DC welcomed back (a limited number of) guests in recent weeks with health and safety protocols in place. (Be sure to check out AN’s non- exhaustive list of new exhibitions to check out this spring at reopened museums in D.C. The first Smithsonian institution to reopen will be the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at the National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia, on May 5, an event that coincides with the 60th anniversary of Alan Shepard becoming the second man, and first American, to travel to space. The National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery are all slated to reopen on May 14. -

Smithsonian Institution Freer Gallery of Art Water Infiltration Remediation – Third Party Review Washington, District of Columbia

Smithsonian Institution Freer Gallery of Art Water Infiltration Remediation – Third Party Review Washington, District of Columbia Circa 1920, the Freer Gallery of Art was designed by Charles A. Platt in the Renaissance Revival style. The Freer Gallery of Art houses over 26,000 objects from the Neolithic to modern eras. It connects to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery using an underground passageway. The building’s facade is composed of v-jointed, rusticated-pink granite block walls terminated by a granite entablature and balustrade. The building walls consist of granite face stone with brick masonry back-up. The masonry back-up wall extends up to the underside of the full depth granite coping stone below the balustrade. A skylight system provides natural light to a secondary translucent skylight in the Gallery ceiling. The asphaltic roof membrane extends from the roof skylights down to the flat surface of the concrete deck and then wraps up the parapet wall, terminating five levels below the top of the masonry back-up wall. In 1993, renovations to the Gallery were completed which included a new copper gutter and roof. The roof was replaced in 2011 due to leaks at the roof drains. Concurrent with the roof installation, the granite mortar joints on the inside and outside faces of the parapet wall above the cornice, including the balustrade and top rail, as well as the exposed brick masonry mortar joints on the inside face of the parapet, were repointed. Hoffmann Architects was retained by Lend Lease (US) Construction, Inc. , on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution, to perform a 3rd-party investigation to determine the causes of water infiltration through the mortar and parapets. -

Dangerous Liaisons Revisited

Asian Art hires logo 15/8/05 8:34 am Page 1 ASIAN ART The newspaper for collectors, dealers, museums and galleries june 2005 £5.00/US$8/€10 The Taj Mahal and the Battle of Air Pollution THE GOVERNMENT OF India buy the more expensive ticket if they courtyard and its cloisters were added announced earlier this year that it is to want to get around the limit. Night subsequently and the complex was restrict the number of daily visitors to viewing is still permitted, but restricted fnally completed in 1653, with the the Taj Mahal in an attempt to to fve nights a month (including full tomb being the central focus of the preserve the 17th-century monument. moon). entire complex of the Taj Mahal. One of the best known buildings in Smog and heavy air pollution has It was inscribed on the World the world, and arguably India’s greatest been yellowing the Taj Mahal for Heritage List in 1983. Although the monument, makes it one of the most- many years and conservationists have Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ), which visited tourist attractions in the world. been fghting through the courts to looks after 40 protected monuments, Millions of mostly Indian tourists visit control the levels of pollution in Agra. including three World Heritage Sites, the Taj Mahal every year and their Te Taj faces numerous threats, not Taj Mahal, Agra Fort and Fatehpur numbers are increasing steadily, as only from air pollution, but also insects, Sikri, delivered a court ban on the use domestic travel becomes easier. -

Ann C. Gunter

Ann C. Gunter Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities Northwestern University Mailing address: Department of Art History 1800 Sherman Ave., Suite 4400 Evanston, IL 60201 Voice mail 847 467-0873 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Columbia University Ph.D. 1976 Columbia University M.Phil. 1975 Columbia University M.A. 1973 Bryn Mawr College A.B. magna cum laude with departmental honors Professional Employment Bertha and Max Dressler Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2013– Professor of Art History, Classics, and in the Humanities, Northwestern University, 2008– Head of Scholarly Publications and Programs, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2004–08 Assistant Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution (1987–92); Associate Curator (1992–2004); Curator (2004–08) Visiting Assistant Professor, Art History Department, Emory University, Atlanta (1986–87) Visiting Assistant Professor, Departments of Art History and Classics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1981–85) Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley (Winter– Spring 1981) Director, American Research Institute in Turkey at Ankara (1978–79) Fellowships, Grants, and Awards Visiting Professor (Directrice d’études), École Pratique des Hautes Études, University of Paris (lecture series to be presented in May 2016) Fritz Thyssen Stiftung 2000–01 -

Puja: Expressions of Hindu Devotion. Guide for Educators. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 992 SO 030 951 AUTHOR Ridley, Sarah TITLE Puja: Expressions of Hindu Devotion. Guide for Educators. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 41p.; Accompanying videotape and three posters not available from ERIC. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Public Affairs, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery/Freer Gallery of Art, MRC 707, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 ($26). For full text: http://www.asia.si.edu/pujaonline. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Context; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Indians; Middle Schools; Multicultural Education; Non Western Civilization; Religion Studies; *Religious Cultural Groups; Secondary Education; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Hindu Art; *Hinduism; India ABSTRACT This teaching packet serves as a unit by itself or as part of preparation unit for a visit to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery to see the exhibition "Puja: Expressions of Hindu Devotion." Focusing on Hindu religious objects found in an art museum, the packet suggests connections between art and world studies themes. In addition, these highly symbolic objects provide much material for discussion of the creation of images, whether in two or three dimensions, in speech, or in music. In this way, study of the objects provides a springboard for creativity in art, language arts, and music. This guide explains that puja is the act of showing reverence to a god, or to aspects of the divine, through invocations, prayers, songs, and rituals. An essential part of puja for the Hindu devotee is making a spiritual connection with a deity (often facilitated through an element of nature, a sculpture, a vessel, a painting, or a print). -

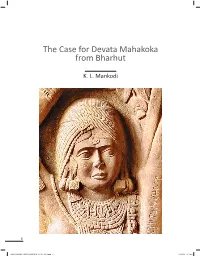

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut K. L. Mankodi 6 FINAL DUMMY CSMVS JOURNAL 16_06_2016.indd 6 17/06/16 8:17 pm IT is assumed that everything worth 10, H. Lűders listed all the Bharhut inscriptions then known knowing about the ancient Buddhist Stupa of Bharhut has in Epigraphia Indica X.1 In the 1940s, during British rule, the already been published and is easily available. For, did not Archaeological Survey of India had proposed a publication Alexander Cunningham, pioneer of Archaeological Survey by Lűders which would present a revised version of of India, who discovered the great site nearly one hundred Cunningham’s original readings of the inscriptions from and forty years ago, himself give an exhaustive description Bharhut. Unfortunately, this project did not materialise. of it together with illustrations of hundreds of remains Later, in 1963, the Archaeological Survey of India published as early as 1879? And did not Cunningham himself, and Bharhut Inscriptions edited by Lűders and revised by E. thereafter Heinrich Lűders, followed by Ernst Waldschmidt Waldschmidt and M. A. Mehendale.2 In between, other and M. A. Mehendale, re-edit and revise the hundreds of books and articles by B. M. Barua-Gangananda Sinha, and inscriptions that Bharhut had yielded? by S. C. Kala have appeared on the subject. For this paper, references to Cunningham and Lűders-Waldschmidt- Mehendale will suffice. Bharhut: discovery and documentation Cunningham, in his explorations in central India during Devata Chulakoka 1873 came across the remains of the ancient stupa at the One sculpture recovered from the ruins and now in the village of Bharhut, twenty kilometres to the south of the Indian Museum bears the inscription Chulakoka Devata, present district headquarters of Satna in Madhya Pradesh the Sanskrit form of which would be Kshudrakoka Devata. -

Smithsonian Intern Handbook

Smithsonian Institution Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Intern Handbook • Welcome to the Smithsonian ... page 3 • Brief History … page 4 • Mission … page 6 • Structure … page 7 • Organization … page 8 • Internship Resources … page 15 • Web Resources … page 15 • Get There … page 17 • Pre-arrival … page 19 • Arrival … page 20 • Departure … page 21 • International … page 21 • General Information … page 22 • Safety and Health … page 23 • Policies … page 24 Smithsonian Intern Orientation Guide (May 2013) Page 2 Welcome to the Smithsonian Institution! As the world’s largest museum complex, the Smithsonian spans 19 museums, the National Zoo, 9 cutting edge research facilities, and 140 extensive education and outreach programs across the world. At any given time, the Smithsonian employs 6,300 staff members, thousands of researchers, volunteers, and hosts 1,300 interns yearly. The Smithsonian is headquartered in Washington, D.C., and operates museums and facilities in New York, Virginia, Maryland, Florida, Massachusetts, Arizona, and Panama. This is an exciting time to be at the Smithsonian, and we hope you will make the most of it. Smithsonian interns learn by doing. By helping us to produce our world class programs, exhibits, and research, you will have an opportunity to make a real impact, develop personally and professionally, and learn from people who are experts in their fields. The Office of Fellowships and Internships (OFI) has gathered the following information to guide you through your internship. If you have any questions, please contact: 202-633-7070 or [email protected]. On behalf of the Office of Fellowships and Internships, best wishes for a rewarding internship! Sincerely, Eric Woodard Director Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Intern Orientation Guide (May 2013) Page 3 The Smithsonian Institution owes its origin to a British scientist named James Smithson, the illegitimate son of the Duke of Northumberland, who died in 1829.