The Case of Apple TV's Aerial Screen Savers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artist's Voice Since 1981 Bombsite

THE ARTIST’S VOICE SINCE 1981 BOMBSITE Peter Campus by John Hanhardt BOMB 68/Summer 1999, ART Peter Campus. Shadow Projection, 1974, video installation. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. My visit with Peter Campus was partially motivated by my desire to see his new work, a set of videotapes entitled Video Ergo Sum that includes Dreams, Steps and Karneval und Jude. These new works proved to be an extraordinary extension of Peter’s earlier engagement with video and marked his renewed commitment to the medium. Along with Vito Acconci, Dara Birnbaum, Gary Hill, Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and Bill Viola, Peter is one of the central artists in the history of the transformation of video into an art form. He holds a distinctive place in contemporary American art through a body of work distinguished by its articulation of a sophisticated poetics of image making dialectically linked to an incisive and subtle exploration of the properties of different media—videotape, video installations, photography, photographic slide installations and digital photography. The video installations and videotapes he created between 1971 and 1978 considered the fashioning of the self through the artist’s and spectator’s relationship to image making. Campus’s investigations into the apparatus of the video system and the relationship of the 1 of 16 camera to the space it occupied were elaborated in a series of installations. In mem [1975], the artist turned the camera onto the body of the specator and then projected the resulting image at an angle onto the gallery wall. -

The Role of Art in Enterprise

Report from the EU H2020 Research and Innovation Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation The Role of Art in Enterprise Tom O’Dea, Ana Alacovska, and Christian Fieseler This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870726. Report of the EU H2020 Research Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation State-of-the-art literature review on the role of Art in enterprise Tom O’Dea1, Ana Alacovska2, and Christian Fieseler3 1 Trinity College, Dublin 2 Copenhagen Business School 3 BI Norwegian Business School This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870726 Suggested citation: O’Dea, T., Alacovska, A., and Fieseler, C. (2020). The Role of Art in Enterprise. Artsformation Report Series, available at: (SSRN) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3716274 About Artsformation: Artsformation is a Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation project that explores the intersection between arts, society and technology Arts- formation aims to understand, analyse, and promote the ways in which the arts can reinforce the social, cultural, economic, and political benefits of the digital transformation. Artsformation strives to support and be part of the process of making our communities resilient and adaptive in the 4th Industrial Revolution through research, innovation and applied artistic practice. To this end, the project organizes arts exhibitions, host artist assemblies, creates new artistic methods to impact the digital transformation positively and reviews the scholarly and practi- cal state of the arts. -

Paul Robeson Galleries

Paul Robeson Galleries Exhibitions 1979 Green Magic April 9 – June 29, 1979 An exhibition consisting of two parts: Green Magic I and Green Magic II. Green Magic I displayed useful plants of northern New Jersey, including history, properties, and myths. Green Magic II displayed plant forms in art of the ‘70’s. Includes the work of Carolyn Brady, Brad Davis, Jim Dine, Tina Girouard, George Green, Hanna Kay, Bob Kushner, Ree Morton, Joseph Raffael, Ned Smyth, Pat Steir, George Sugarman, Fumio Yoshimura, and Barbara Zucker. Senior Thesis Exhibition May 7 – June 1, 1979 An annual exhibition of work by graduating Fine Arts seniors from Rutgers – Newark. Includes the work of Hugo Bastidas, Connie Bower, K. Stacey Clarke, Joseph Clarke, Stephen Delceg, Rose Mary Gonnella, Jean Hom, John Johnstone, Mathilda Munier, Susan Rothauser, Michael Rizzo, Ulana Salewycz, Carol Somers Kathryn M. Walsh. Jazz Images June 19 – September 14, 1979 An exhibition displaying the work of black photographers photographing jazz. The show focused on the Institute of Jazz Studies of Rutgers University and contemporary black photographers who use jazz musicians and their environment as subject matter. The aim of the exhibition was to emphasize the importance of jazz as a serious art form and to familiarize the general public with the Jazz Institute. The black photographers whose work was exhibited were chosen because their compositions specifically reflect personal interpretations of the jazz idiom. Includes the work of Anthony Barboza, Rahman Batin, Leroy Henderson, Milt Hinton, and Chuck Stewart. Paul Robeson Campus Center Rutgers – The State University of New Jersey 350 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. -

A One Day Exhibition

New Video at EAI: A One Day Exhibition New Video at EAI: A One Day Exhibition Saturday, September 8, 2001 12 - 6 pm, 535 West 22 Street, 5th floor New Video at EAI is presented in conjunction with the Downtown Arts Festival's Chelsea Art Walk day and with the cooperation of Dia Center for the Arts. Monitor 1 Joan Jonas Mirage 2, 2000, 30 min, b&w Mirage 2 is a reconsideration of the past, a new work edited by Jonas from footage recorded in the 1970s as part of her Mirage project. Eder Santos Projeto Apollo, 2000, 4 min, color Combining artfully designed sets and digital processing, Santos recreates the historic Apollo lunar landing, using simulation to interrogate representation. Ursula Hodel Cinderella 2001, 2001, 12 min, color Cinderella 2001 is a vibrant performance tape with an unnerving, compulsive narrative concerned with image and obsession. Phyllis Baldino 16 Minutes Lost, 2000, 16:54 min, color Baldino's 16 Minutes Lost is the perfect portrayal of scatterbrainedness, testament to the clutter of modern living and the inevitable failings of manmade systems. Monitor 2 Cheryl Donegan The Janice tapes: Lieder, 2000, 4 min, color; Whoa Whoa Studio (for Courbet), 2000, 4:30 min, color; Cellardoor, 2000, 2 min, silent In her new performance trilogy, Donegan sets up a series of charged relationships -- between artist and model, art object and artistic "gesture," performer and viewer. Mike Kelley Superman Recites Selections from 'The Bell Jar' and Other Works, 1999, 7:19 min, color, sound "In a dark no-place evocative of Superman?s own psychic ?Fortress of Solitude? the alienated Man of Steel recites those sections of Plath?s writings that utilize the image of the bell jar." Mike Kelley Kristin Lucas Involuntary Reception, 2000, 16:45 min, color Involuntary Reception is a double-imaged, double-edged report from a young woman lost in the telecommunications ether. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

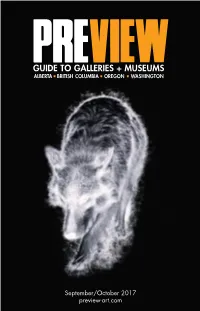

September/October 2017 Preview-Art.Com

September/October 2017 preview-art.com Installation Storage Shipping Transport Framing Providing expert handling of your fine art for over thirty years. 155 West 7th Avenue, Vancouver, BC Canada V5Y 1L8 604 876 3303 denbighfas.com [email protected] Installation Storage Shipping Transport Framing Providing expert handling of your fine art for over thirty years. 155 West 7th Avenue, Vancouver, BC Canada V5Y 1L8 604 876 3303 denbighfas.com [email protected] BRITISH COLUMBIA ALBERTA Laxgalts’ap Prince Rupert Prince George St. Albert Skidegate Edmonton HAIDA GWAII North Vancouver Deep Cove West Vancouver Port Moody Williams Lake Vancouver Coquitlam Burnaby Maple Ridge Richmond New Westminster Chilliwack Banff Calgary Surrey Fort Langley Salmon Arm Tsawwassen White Rock Abbotsford Kamloops Black Diamond Vernon Campbell River Courtenay Whistler Kelowna Medicine Hat Cumberland Roberts Creek Penticton Nelson Qualicum Beach Vancouver Lethbridge Port Alberni (see map above) Grand Forks Castlegar Nanaimo Salt Spring Is. Bellingham Victoria La Conner Friday Harbor Everett Port Angeles Spokane Bellevue Bainbridge Is. Seattle Tacoma WASHINGTON Pacific Ocean Astoria Cannon Beach Portland Salem OREGON 6 PREVIEW n SEP-OCT 2017 H OPEN LATE ON FIRST THURSDAYS September/October 2017 Vol. 31 No.4 ALBERTA PREVIEWS & FEATURES 8 Banff, Black Diamond, Calgary 10 Yechel Gagnon: Midwinter Thaw 13 Edmonton Newzones 14 Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, St. Albert 12 Citizens of Craft Alberta Craft Gallery, Calgary BRITISH COLUMBIA 15 Cutline: From the Archives of the Globe -

Campus' Closed-Circuit Slavko Kacunko Slavko Kacunko

Campus' Closed-Ci rcu it Campus' Closed-Circuit Slavko Kacunko Slavko Kacunko Lr) oo oo f_E Die Uberwindung der empha- rischen Praktiken zwischen dem ln order to arrive at an impartial As we all know, the writing ai his- ==OC) Closet l- l- tischen 0pposition zwischen dem hermeneutischen Kontextuber- view of media art that derives its tory like 'directness' * is a C)(J - schen 13Etl (I)(l) ,spezifisch Medialen' und dem druss und semiotischer Kontext- pertinence from the spheres of construct. A discourse abou; the <t) a gerat oo ,historisch Gewordenen' ist eine euphorie. both media theory and art history, 'directness' of media from an (J (J br/Pr Voraussetzung fiir den unbefange- Das Historieschreiben ist ebenso it is essential to overcome the art-historical perspective mev -(n -u) auditit nen Blick auf die Medienkunst, wie die,Unmittelbarkeit' bekannt- emphatic opposition between what illuminate the conflux of technical (f_== o_ lung, t (\,EE (g der seine Kompetenzen sowohl lich eine Konstruktion. Ein Diskurs is 'specific to media' and what and human viewpoints and rrreigh (JO ftir die Bereich Medien- 'has aus dem der [iber die mediale,Unmittelbarkeit' become historical'. up the opportunities and the bildet. theorie wie auch der Kunstge- aus kunsthistorischer Perspektive A future history of media art will dangers brought about by their sowol schichte beziehen will. Eine krlnfti- kann das Ndherbringen von have to counter 'post-historical' convergence, even their mul,.:al deren ge Medienkunstgeschichte wird technischen und menschlichen apocalyptic paranoia and fantasies penetration, schen der,posthistorischen' End zeitpar a- Sichtweisen durchleuchten und die of abolition with a thesis of conti- The attempts made during trie So ist noia und den Aufhebungsfantasien Chancen und Gefahren ihrer An- nuity which does not construct early period of 'video art'to differ- des e eine Kontinuititsthese entgegen niherung und lnterpenetration 'pre-established harmonies' in entiate it from other media r;f des b setzen mtlssen, welche nicht abwagen. -

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents

Henriette Huldisch Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents 5 Director’s Foreword 9 Acknowledgments 13 Before and Besides Projection: Notes on Video Sculpture, 1974–1995 Henriette Huldisch Artist Entries Emily Watlington 57 Dara Birnbaum 81 Tony Oursler 61 Ernst Caramelle 85 Nam June Paik 65 Takahiko Iimura 89 Friederike Pezold 69 Shigeko Kubota 93 Adrian Piper 73 Mary Lucier 97 Diana Thater 77 Muntadas 101 Maria Vedder 121 Time Turned into Space: Some Aspects of Video Sculpture Edith Decker-Phillips 135 List of Works 138 Contributors 140 Lenders to the Exhibition 141 MIT List Visual Arts Center 5 Director’s Foreword It is not news that today screens occupy a vast amount of our time. Nor is it news that screens have not always been so pervasive. Some readers will remember a time when screens did not accompany our every move, while others were literally greeted with the flash of a digital cam- era at the moment they were born. Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 showcases a generation of artists who engaged with monitors as sculptural objects before they were replaced by video projectors in the gallery and long before we carried them in our pockets. Curator Henriette Huldisch has brought together works by Dara Birnbaum, Ernst Caramelle, Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota, Mary Lucier, Muntadas, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Friederike Pezold, Adrian Piper, Diana Thater, and Maria Vedder to consider the ways in which artists have used the monitor conceptually and aesthetically. Despite their innovative experimentation and per- sistent relevance, many of the sculptures in this exhibition have not been seen for some time—take, for example, Shigeko Kubota’s River (1979–81), which was part of the 1983 Whitney Biennial but has been in storage for decades. -

La Videodanza 184 James Seawright, P

orizzonti La pubblicazione del presente volume è stata realizzata con il contributo dell’Università degli Studi di Torino, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici. © edizioni kaplan 2020 Via Saluzzo, 42 bis – 10125 Torino Tel. e fax 011-7495609 [email protected] www.edizionikaplan.com ISBN 978-88-99559-41-0 In copertina: immagine di Alessandro Amaducci Alessandro Amaducci Screendance Sperimentazioni visive intorno al corpo tra film, video e computer grafica k a p l a n Indice Introduzione 11 Screendance 11 Le differenti forme della screendance, p. 13 Risorse web, p. 17 Capitolo 1 18 Dance film: il cinema di danza 18 La danza delle forme, p. 18 Gli albori del film di danza, p. 22 Marie Louise Fuller, p. 22 Danza e natura, p. 23 Charles Allen, Francis Trevelyan Miller, p. 24 Emlen Etting, p. 24 Dudley Murphy, p. 25 Coreografie animate: danze macabre e Surrealismo, p. 27 Walt Disney, p. 28 Le mani che danzano, p. 29 Stella F. Simon, Miklós Bándy (Nicolas Baudy), p. 29 Norman Bel Goddes, p. 30 Maya Deren, p. 31 Gli esordi della documentazione potenziata: Martha Graham, p. 40 Peter Glushnakov, p. 40 Alexander Hammid (Alexander Siegfried Hackenschmied), p. 41 Filmmaker sperimentali e danza, p. 43 Len Lye, p. 43 Sara Kathryn Arledge, p. 45 Shirley Clarke, p. 47 Ed Emshwiller, p. 50 Bruce Conner, p. 57 Norman McLaren, p. 59 Richard O. Moore, p. 63 5 Doris Chase, p. 68 Amy Greenfield, p. 69 Téo Hernandez, p. 76 Henry Hills, p. 78 I coreografi diventano registi, p. 80 Yvonne Rainer, p. 81 Twyla Tharp, p. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Press Release

Positions I Bruce and Norman Yonemoto (in collaboration with Mike Kelley) Kappa (1986) 7 – 11 July 2015 Evening Screening and & Drinks Reception, Thursday 9 July, 6-8pm For the first week of Positions—a series of five week-long, single channel video installations running through July and August 2015—Hales Gallery is delighted to present Bruce and Norman Yonemoto’s 1986 film Kappa, made in collaboration with artist Mike Kelley. Bruce and Norman Yonemoto are known for their pioneering body of work deconstructing and exploring mythologies created within mass media culture, as well as for their independent video and installation work produced in more recent years. Beginning in 1976, the artists would appropriate the styles of popular media forms (soap operas, Hollywood melodramas and television advertising) to create ironic, stylised fictions exposing the media’s manipulation of reality, fantasy and identity. Underlying their critique of culture is the brothers’ Japanese-American heritage and their upbringing in California’s Silicon Valley, as well as their proximity to Hollywood and the entertainment industry. The film Kappa combines the Greek myth of Oedipus with the figure of the ‘Kappa’ from Japanese folklore to explore the presence and relative positions of Eastern and Western mythologies in everyday life. The Kappa (a freshwater deity or sprite known for its sexual and violent behaviours, played by Mike Kelley) encounters an Oedipal scene reframed in a contemporary south-Californian setting, watching and commenting as Jocasta (Oedipus’s mother, played by famous Warhol Factory member and B-movie actress Mary Woronov) and Eddie (a pun on ‘Oedipus’, played by Eddie Ruscha, son of artist Ed Ruscha) consummate their dangerous desire. -

5 Old-School NYC Video Artists You Should Know (And Follow)

https://hyperallergic.com/121286/5-old-school-nyc-video-artists-you-should-know-and-follow/[9/27/18, 2:47:40 PM] � � � � ARTICLES 5 Old-School NYC Video Artists You Should Know (and Follow) Jason Varone April 18, 2014 Peter Campus, still from “Kiva” (1971) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic) Most written accounts of the origins of video art trace the medium back to the Sony Portapak, the first affordable, battery-powered, portable video-recording device that could be operated by a single individual. The resulting democratization of video was quickly seen as having radical potential. Artists could challenge the rising influence of broadcast media. All of a sudden, the barriers to working in this time-based medium were removed. Looking at the work of a few pioneers, specifically those on the scene in New York City, it’s obvious that technology was a catalyst for a new type of electronic art; these artists were trailblazers in both fields. And this remains true of their current work, 37 years after the first Portapak hit the market. Here, then, are five old-school NYC video artists whose work you should know about and (still) be following. Mary Lucier Mary Lucier (b. 1944, Bucyrus, OH) burned vidicon tubes with lasers and pointed the video camera directly at the sun, testing the limits of technology in her pieces from the 1970s, such as “Dawn Burn” and “Fire Writing.” She’s also known for telling subtle but powerful human stories in multichannel video installations, and the natural landscape is featured prominently in her current work.