The Artistic Legacy of Georgia O'keeffe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art History and Arthuk Submitted by David Haskins Fine Arts

Art History ~eminar NATUR8: lN TH8 LlV8~ Of G~UNG!A O'K~EfFhl AND ARTHUk DOVE Submitted by David Haskins fine Arts Department ln partial fulfillment or the requirements tor the Degree or Master ot fine Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado ~pring l~~<O LlS'l' OE' .t' l.l7UR!!.:S 1. Nature symbolized No. 2, 1914 P as t e l on 1 i n en , 1 8 " x 2 1 !::> I 8 ·· The Art Institute or Chicago, Altred Stieglitz collection 2. 1-rnsJ.c - Pmk and Blue 11, 1919 01.l on canvas ..:S~ 1/2" x 2'.::1" Emily .t'isher Landau J . J:'og Horns, 19 2 ~ 011 on canvas, 18" x 26" Colorado Springs .t' ine Arts Center Gitt ot Oliver ti. James 4. Black Ho.LJyhock, l:Jlue Larkspur, 19 L 9 Uil on canvas, 3b" x 30" ~he Metropolitan Museum or Art ~. P1eJ.ds Ot Urain As Seen Prom 'l'ra.ln, 1~31 Oil on canvas, 24" x 34" Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY Gitt ot Seymour H. Knox 6 . Nature J:1orms, Gaspe, 19 3 2 Oil on canvas, 10" x ~4" hlstate ot Georgia O'Keette 1. JacJ-:-In-'11he-Puipit no. V, l:t30 Oil on canvas, 48" x 30" Estate ot Georgia o Keette 8. J'Villow, 19 3 9 Watercolor on paper, ~" x I" Ph1ll1ps Memorial Gallery ~. J:'llght, 1~43 wax emulsion on canvas, 12" x ~0" Elmira Bier, Arlington, Virginia i LIS 1r Of' l;' lGURES 10. Black .tJlace lJ, 1 :144 O i l on canvas , ~ 3 II 8 " x 3 0 '' Metropolitan Museum ot Art Altred Stieglitz Collection 11. -

Arthur Dove: a Retrospective

Arthur Dove: A Retrospective 1997-1998 Finding Aid The Phillips Collection Library and Archives 1600 21st Street NW Washington D.C. 20009 www.phillipscollection.org CURATORIAL RECORDS IN THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION ARCHIVES INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION Collection Title: Arthur Dove: A Retrospective; exhibition records Author/Creator: The Phillips Collection Curatorial Department. Beth Turner, Senior Curator, Elsa Smithgall, Curatorial Assistant and her predecessor, Leigh Bullard Weisblat, Assistant Curator Size: 3.3 linear feet; 8 document boxes Bulk Dates: 1996-1997 Inclusive Dates: 1887-1998 Repository: The Phillips Collection Archives, 1600 21st St NW, Washington, DC 20009 INFORMATION FOR USERS OF THE COLLECTION Restrictions: The collection contains restricted materials. Please contact Karen Schneider, Librarian, with any questions regarding access. Handling Requirements: none Preferred Citation: Arthur Dove: A Retrospective. The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington, D.C. Publication and Reproduction Rights: See Karen Schneider, Librarian, for further information and to obtain required forms. SPECIAL NOTE: Most of the Research Series materials in this collection were photocopied or acquired by The Phillips Collection with the appropriate permissions and/or payments, but are not owned by The Phillips Collection Archives, which consequently cannot grant copying, publication or reproduction rights to these materials. For these permissions, the originating repository must be contacted, which is the sole responsibility of the researcher (see „Related Material‟ below for some contact information). ABSTRACT Arthur Dove: A Retrospective exhibition records contain materials created and collected by the Curatorial Department of The Phillips Collection during the course of organizing the exhibition. Included are research, catalogue, and exhibition planning files. Files for a one-gallery exhibition, Arthur Dove: Works on Paper, held during the dates of Arthur Dove: A Retrospective, have been made into their own collection housed in The Phillips Collection Archives. -

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Arthur Dove American, 1880 - 1946 Moon 1935 oil on canvas overall: 88.9 x 63.5 cm (35 x 25 in.) framed: 94.6 x 69.2 x 5.1 cm (37 1/4 x 27 1/4 x 2 in.) Inscription: lower center: Dove Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth 2000.39.1 ENTRY In the summer of 1933, after much hesitation, Arthur Dove moved back to his family home in Geneva, New York. [1] Although he felt there was “something terrible about ‘Up State,’” and described the prospect of returning to his hometown as “like walking on the bottom under water,” he and his wife Helen “Reds” Torr had endured grinding poverty during the early years of the Great Depression, and he knew that the struggle to survive was sapping his ability to focus on his painting. [2] With his mother's death earlier in the year, in Geneva Dove and Reds could live for free on the family property, farm and forage for food, and hope that his paintings would at least pay for more materials. Dove’s years in Geneva from 1933 to 1938 would prove to be remarkably productive. Shortly before he returned, Duncan Phillips agreed to provide him with a monthly stipend in exchange for paintings. [3] Although the payments were modest and fluctuated, and the checks occasionally late, for the first time in many years Dove had a steady source of income. Gradually, as he came to see that he could perhaps survive in his old haunts, his spirits were restored and his confidence returned. -

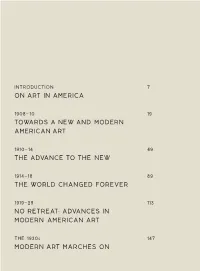

On Art in America Towards a New and Modern

INTRODUCTION 7 ON ART IN AMERICA 1908–10 19 TOWARDS A NEW AND MODERN AMERICAN ART 1910–14 49 THE ADVANCE TO THE NEW 1914–18 89 THE WORLD CHANGED FOREVER 1919–29 113 NO RETREAT: ADVANCES IN MODERN AMERICAN ART THE 1930S 147 MODERN ART MARCHES ON MAIA_pp1–144_Chapters1234.indd 4 09/11/2015 12:04 THE 1940S 185 A NEW WORLD ORDER THE 1950S 241 A NEW DEPTH IN AMERICAN ART THE 1960S 295 FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE NOTES 334 BIBLIOGRAPHY 342 INDEX 344 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 352 MAIA_pp1–144_Chapters1234.indd 5 30/10/2015 15:39 INTRODUCTION: ON ART IN AMERICA This book is a history – one of the many possible histories that could be written – of the years 1908 to 1968, the richest, most dynamic period of American art. It surveys the best of modern art in America made by four generations of exceptionally talented artists spanning the early years of the twentieth century to the late 1960s. Sometimes, familiar pictures will be examined in new contexts; at other times, little or virtually unknown works will be explored, all standing side by side, not always as equals, but all worthy of respect and attention. In 1970 Barnett Newman said: ‘about 25 years ago … painting was dead … I had to start from scratch as if painting didn’t exist.’1 But he was failing to acknowledge his debt to the American artists who had come before him. He was not the only one to think in this way. As art in the United States gained international attention after 1945, earlier American art was cast off by critics and curators as a kind of demented uncle, in favour of establishing a more elevated pedigree, a celebrated cast of exalted Europeans such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. -

American Paintings, 1900–1945

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 American Paintings, 1900–1945 Published September 29, 2016 Generated September 29, 2016 To cite: Nancy Anderson, Charles Brock, Sarah Cash, Harry Cooper, Ruth Fine, Adam Greenhalgh, Sarah Greenough, Franklin Kelly, Dorothy Moss, Robert Torchia, Jennifer Wingate, American Paintings, 1900–1945, NGA Online Editions, http://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/american-paintings-1900-1945/2016-09-29 (accessed September 29, 2016). American Paintings, 1900–1945 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 CONTENTS 01 American Modernism and the National Gallery of Art 40 Notes to the Reader 46 Credits and Acknowledgments 50 Bellows, George 53 Blue Morning 62 Both Members of This Club 76 Club Night 95 Forty-two Kids 114 Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett) 121 The Lone Tenement 130 New York 141 Bluemner, Oscar F. 144 Imagination 152 Bruce, Patrick Henry 154 Peinture/Nature Morte 164 Davis, Stuart 167 Multiple Views 176 Study for "Swing Landscape" 186 Douglas, Aaron 190 Into Bondage 203 The Judgment Day 221 Dove, Arthur 224 Moon 235 Space Divided by Line Motive Contents © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 244 Hartley, Marsden 248 The Aero 259 Berlin Abstraction 270 Maine Woods 278 Mount Katahdin, Maine 287 Henri, Robert 290 Snow in New York 299 Hopper, Edward 303 Cape Cod Evening 319 Ground Swell 336 Kent, Rockwell 340 Citadel 349 Kuniyoshi, Yasuo 352 Cows in Pasture 363 Marin, John 367 Grey Sea 374 The Written Sea 383 O'Keeffe, Georgia 386 Jack-in-Pulpit - No. -

Arthur Dove, Gray Woman, 1940 Oil on Canvas, 27 X 34 In

Arthur Dove, Gray Woman, 1940 Oil on canvas, 27 x 34 in. (68.6 x 86.4 cm.) New York Private Collection Known for his innovative, stylized paintings, Arthur Garfield Dove (1880–1946) is considered to have been at the forefront of the early 20th century American avant-garde, having been one of the first American artists to explore non-representational imagery. Through abstraction and bold color, Dove painted nature in its most simplified and organic form. Dove explained: “Why not make things look like nature? Because I do not consider that important and it is my nature to make them this way. I should like to take wind and water and sand as a motif and work with them, but it has to be simplified in most cases to color and force lines and substances, just as music is done with sound.”1 Gray Woman (Fig. 1) expounds upon the raw sense of nature through the power of color and line. Specifically, it takes a step further with the rare feature of portraiture, an uncommon element within Dove’s span of work. While we cannot know for certain who exactly is represented in this portrait, we can explore different theories based on the reverse of the canvas. Painted on the reverse are inventory identifications, PG. 65.54 (Fig. 2) and a frame tag from M. Grieve Co., Inc. (Fig. 3), a framing company that was a famous for their wood carving. The company was active in New York City between 1924 and 1955 when the company was dissolved, and their complete inventory was sold at auction.2 Most importantly, however, the painting title, date, and gallery (Fig. -

Arthur G. Dove

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz American, 1864 - 1946 Arthur G. Dove 1923 gelatin silver print sheet (trimmed to image): 24.1 x 19.1 cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.) Alfred Stieglitz Collection 1949.3.345 Stieglitz Estate Number 80E Key Set Number 855 KEY SET ENTRY Related Key Set Photographs Arthur G. Dove 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz Alfred Stieglitz Arthur G. Dove Arthur G. Dove 1923 1923 palladium print palladium print Key Set Number 856 Key Set Number 857 Remarks Dove is depicted in front of his painting Gear, c. 1922 (Morgan 22.2). On 18 July 1923 Stieglitz wrote to Arthur Dove that Rosenfeld was “writing his book & chapter on you.” Stieglitz continued that he had just gotten the “new negatives of you . you moved in the most interesting one . have a profile which is ghastly in a way but an addition. There is a full face which might be used for the book. .The first shot we made with your painting as ‘background.’ It just misses fine. Is photographically very fine” (Arthur Dove Papers, AAA). Other Collections A print corresponding with this photograph can also be found in the following collection(s): The Museum of Modern Art, New York, SC 97.88 (inscribed: With Permission An American Place / Arthur G. Dove (Photo by Alfred Stieglitz) / This photo must be returned to Alfred Stieglitz. 509 Madison Ave. -

Art Cram Kit ®

19 2 0 1 3 YEAR S 2 014 DOING OUR BES EDITIO N T, S O YOU CAN DO Y ART OURS ART Art in the CRAM KIT Early 1900s EDITOR ALPACA-IN-CHIEF Nicole Chu Daniel Berdichevsky ® the World Scholar’s Cup® ART CRAM KIT ® A Word from the Author ................................................................................................................................... 2 Elements of Art, Principles of Composition, and Techniques ........................................................................ 3 Introduction to Art History ............................................................................................................................... 8 Western Art History .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Nonwestern Art History .................................................................................................................................. 20 Woman with a Hat (1905) ............................................................................................................................. 22 Ma Jolie (1911-12) ............................................................................................................................................ 23 Street, Berlin (1913) ......................................................................................................................................... 24 Little Painting with Yellow (Improvisation) (1914) .................................................................................... -

Art from Europe and America, 1850-1950

Art from Europe and America, 1850-1950 Gallery 14 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 1 0 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sunday 1 - 5p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Auguste Rodin French, 1840 – 1917 Head of Balzac, 1897 bronze Ackland Fund, 63.27.1 About the Art • Nothing is subtle about this small head of the French author Honoré de Balzac. The profile view shows a protruding brow, nose, and mouth, and the hair falls in heavy masses. • Auguste Rodin made this sculpture as part of a major commission for a monument to Balzac. He began working on the commission in 1891 and spent seven more years on it. Neither the head nor the body of Rodin’s sculpture conformed to critical or public expectations for a commemorative monument, including a realistic portrait likeness. Consequently, another artist ultimately got the commission. About the Artist 1840: Born November 12 in Paris, France 1854: Began training as an artist 1871-76: Worked in Belgium 1876: Traveled to Italy 1880: Worked for the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory; received the commission for one of his most famous works, monumental bronze doors called The Gates of Hell 1882: Met sculptor Camille Claudel, who became Rodin’s pupil, lover, and trusted studio assistant. Claudel is believed to have created whole and partial figures for The Gates of Hell 1896: His nude sculpture of the French author Victor Hugo created a scandal 1897: Made the Ackland’s Head of Balzac 1898: Exhibited his monument to Balzac and created another scandal 1917: Died November 17 in Meudon, France 2 Edgar Degas French, 1834 – 1917 Spanish Dance, c. -

Dove/O'keeffe: Circles of Influence Was Organized by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

Dove/O’Keeffe Circles of Influence Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) is celebrated as one of the most significant American artists of the twentieth century. Yet one aspect of her early development is frequently overlooked: O’Keeffe credited the work of Arthur Dove (1880–1946) as her primary introduction to modern art. Dove, acknowledged as America’s first abstract painter, used colorful, dynamic forms to reflect his communion with June 7–September 7, 2009 the natural world—a passion shared by O’Keeffe. Introduced to one another by the photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), Dove and O’Keeffe main- tained a lifelong respect for each other’s work. Over the course of several decades, their artistic dialogue yielded a form of modernism grounded in their emotional responses to nature, and their profound aesthetic connection helped shape the course of art in America. Dove/O'Keeffe: Circles of Influence was organized by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. It is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. By the 1930s, O’Keeffe was dividing her time between New York and New Mexico, returning east only a few times a year to visit Stieglitz. Retreating to her home outside Santa Fe, O’Keeffe moved away from abstraction toward more representational painting. This new direction generated some of her most iconic work: paintings of skulls, flowers, and the southwestern landscape. Around the same time, Dove and Torr moved to Dove’s hometown of Geneva, New York, and later to Long Island. -

A Brief Summary of the Picture Frames Designed and Used by Georgia O

Frames of Preference: A brief summary of the picture frames designed and used by Georgia O’Keeffe Dale Kronkright, Head of Conservation, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Gokmconservation.org [email protected] The exhibition installation photographs of O’Keeffe’s first solo exhibition in 1923 at the Anderson Galleries document the earliest frame profiles authorized by Georgia O’Keeffe. These frames were fabricated and finished by the Manhattan artist and picture framer George F. Of, whose shop was located at 126 West 57th Street, New York. Shown in the photos taken by Alfred Stieglitz is a flat face, “L” profile wood moulding with evenly rounded edges, gilded in 12K silver tone and also in a lacquered black finish. There were also frames executed using an Ogee moulding finished in 12K, and her now- famous “clam shell” moulding finished in 12K over grey bole as well as occasionally painted in black lacquer. A simple half-round face, bull-nose moulding, finished in 12K frame profile is also seen on several works. All of the frames included a sheet of glass to protect the works. There are extant examples of each of these four profiles in private and public collections, all with the order specification written in George Of’s handwriting. One year later, the Stieglitz photographs of the 1924 exhibition demonstrate that all the frames appear exclusively in the 12K finish and that the clam shell and flat face profiles dominate, with the Ogee frame visible on only one work. While there are few Anderson-Intimate Gallery photos from 1925 – 1929, the flat face and clam shells are solely visible. -

The Michael Scharf Family Collection Leads Christie's

PRESS RELEASE | N E W Y O R K FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2 M A Y 2019 THE MICHAEL SCHARF FAMILY COLLECTION LEADS CHRISTIE’S AMERICAN ART MAY 22 SALE Georgia O’Keeffe, Inside Red Canna, 1919, Estimate: $4,000,000 - $6,000,000 New York – Christie’s is honored to announce The Michael Scharf Family Collection will lead the American Art sale on May 22. Considered one of the finest collections of American Modernism, this impressive group of twenty- eight paintings offers a strong representation from the Stieglitz Circle with works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove, as well as exceptional early explorations into abstraction by artists including Max Weber and Charles Green Shaw. Michael Scharf began his collection of American Modernism in 1972 when he purchased Arthur Dove’s Parabola and began to study the artist and his contemporaries. His collecting habits, however, were founded during his childhood with serial collections of stamps, porcelain pugs, early editions of Elizabethan plays and British literature, and early sixteenth-century Hebrew books printed in Constantinople. Michael Scharf comments, “The more I studied, the more I came to believe Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, Max Weber, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin were important artists who were responsible for instigating a transformation in the development of Modern American art. Also, the purchase of Parabola caused a bee to land in my bonnet. The bee stung me into activity, and a burning interest developed. Thus the Collection was born.” Eric Widing, Deputy Chairman, American Art, Christie’s remarks, “Over many decades, Michael Scharf assembled an authoritative collection which represents, in depth, the emergence of modernism in America.