Modernism American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 January 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Harding, J. (2015) 'European Avant-Garde coteries and the Modernist Magazine.', Modernism/modernity., 22 (4). pp. 811-820. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2015 by Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modernism/modernity 22:4 (2015), 811-820. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine Jason Harding Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2015, pp. 811-820 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605720 Access provided by Durham University (24 Jan 2017 12:36 GMT) Review Essay European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine By Jason Harding, Durham University MODERNISM / modernity The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist VOLUME TWENTY TWO, Magazines: Volume III, Europe 1880–1940. -

The Street—Design for a Poster

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz (editor/publisher) after Various Artists Alfred Stieglitz American, 1864 - 1946 The Street—Design for a Poster 1900/1901, printed 1903 photogravure image: 17.6 × 13.2 cm (6 15/16 × 5 3/16 in.) Alfred Stieglitz Collection 1949.3.1270.34 Key Set Number 266 Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art KEY SET ENTRY Related Key Set Photographs The Street—Design for a Poster 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Alfred Stieglitz Key Set Alfred Stieglitz Alfred Stieglitz The Street, Fifth Avenue Fifth Avenue—30th Street 1900/1901, printed 1903/1904 1900/1901, printed 1929/1937 photogravure gelatin silver print Key Set Number 267 Key Set Number 268 same negative same negative Remarks The date is based on stylistic similarities to Spring Showers—The Street Cleaner (Key Set number 269) and Spring Showers—The Coach (Camera Notes 5:3 [January 1902], pl. A). This photograph was made at Fifth Avenue and 30th Street with a Bausch & Lomb Extra Rapid Universal lens, and won a grand prize of $300 in the 1903 “Bausch & Lomb Quarter-Century Competition”(see Camera Work 5 [January 1904], 53; and The American Amateur Photographer 16 [February 1904], 92). Lifetime Exhibitions A print from the same negative—perhaps a photograph from the Gallery’s collection—appeared in the following exhibition(s) during Alfred Stieglitz’s lifetime: 1903, Hamburg (no. 424, as The Street, photogravure) 1903, San Francisco (no. 34a, as The Street—Winter) 1904, Washington (no. -

My New Cover.Pptx

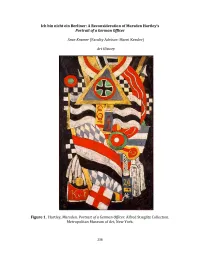

Ich bin nicht ein Berliner: A Reconsideration of Marsden Hartley's Portrait of a German Officer Sean Kramer (FacultyAdvisor: Marni Kessler) Art History Figure I7 8artley9 Marsden7 Portrait of a German Officer. Alfred ;tie<lit= >ollection7 Metro?olitan Museum of Art9 New York. 236 German Officer with a formal analysis of This painting, executed in November 1914, the painting. I then use semiotic theory to shows Hartley's assimilation of both Cubism begin to unpack notions of a singular, (the collagelike juxtapositions of visual fragments) and German Expressionism (the "correct" interpretation of the painting coarse brushwork and dramatic use of bright and to emphasize the multiform nature of colors and black). In 1916 the artist denied that reception. In this section, I seek to the objects in the painting had any special establish that the artist's personal meaning (perhaps as a defensive measure to connection to the artwork is not ward off any attacks provoked by the intense anti-German sentiment in America at the time). necessarily the most important However, his purposeful inclusion of medals, interpretive guideline for working with banners, military insignia, the Iron Cross, and this image. I then use examples of letters the German imperial flag does invoke a specific and numerals within the work to sense of Germany during World War I as well illustrate the plurality of cultural and as a collective psychological and physical linguistic processes which inform portrait of a particular officer.1 viewership of the painting. Meanings in a text, I posit, rely on the interaction between the contexts of the viewer and of This quotation comes from a section the author. -

Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’S 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann Lecture Transcript

MARSDEN HARTLEY ON CAPE ANN : HARTLEY’S 16 YEAR RELATIONSHIP WITH CAPE ANN LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Elyssa East Date: 8/18/2012 Runtime: 0:56:10 Camera Operator: unknown Identification: VL46 ; Video Lecture #46 Citation: East, Elyssa. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann : Hartley’s 16 Year Relationship with Cape Ann.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 8/18/2012. VL46, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for perMission to publish Material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Video Description: 2012 Press Release Subject List: Trudi Olivetti, 6/24/2020 Transcript: Linda Berard, 4/15/2020. Video Description FroM 2012 Press Release: In 1931, the AMerican Early Modernist painter Marsden Hartley spent a life-altering suMMer in Dogtown. But Hartley had a long-standing relationship with Cape Ann that began years earlier. Elyssa East, author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, will discuss Hartley's sixteen-year relationship with Cape Ann and how it Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann – VL46 – page 2 changed his life and work. “Marsden Hartley on Cape Ann” is offered in conjunction with the special exhibition Marsden Hartley: Soliloquy in Dogtown, which is on display at the Cape Ann MuseuM through October 14. The lecture is generously sponsored by the Cape Ann Savings Bank. Elyssa East is the author of Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, which won the 2010 P.E.N. New England/L. L. Winship award in Nonfiction. A Boston Globe bestseller, Dogtown was named a “Must-Read Book” by the Massachusetts Book Awards and an Editors’ Choice Selection of the New York TiMes Sunday Book Review. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Artist Resources – Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Artist Resources – Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) Alfred Stieglitz Collection and Archive, Art Institute of Chicago The Key Set Stieglitz Collection, National Gallery of Art Stieglitz at The Getty Stieglitz and Camera Work collection, Princeton University Art Museum Explore The National Gallery’s timeline of all known Stieglitz exhibitions, spanning from 1888 to 1946. View archival documents from MoMA’s 1947 exhibition, which comprised two floors and paired Stieglitz’s photography with his private art collection. The following year, MoMA introduced Photo-Secession (American Photography 1902-1910), organized by surviving co-founder Edward Steichen and featuring photography from the the journal Camera Work. The 1999 PBS American Master’s documentary, Alfred Stieglitz: The Eloquent Eye, charts the photographer’s immense influence and innovation, featuring intimate interviews with his widow, the painter Georgia O’Keefe, museum curators, and scholars. “What is of greatest importance is to hold a moment, to record something so completely that those who see it will relive an equivalent of what has been expressed,“ Stieglitz reflects in recorded audio of his writing, which is threaded throughout the film. Stieglitz, 1934 Photographer: Imogen Cunningham Smithsonian Magazine profiled Stieglitz in 2002 in honor of The National Gallery’s retrospective. Stieglitz was the subject of the NGA’s first exhibition dedicated exclusively to photography, in 1958. In 2011, The Metropolitan Museum of Art debuted the first large-scale exhibition of Stieglitz’s personal collection, acquired by the museum in 1949. Over 200 works display the photographer’s influence with his contemporaries and successive generations, including, among others, works by: Georgia O'Keeffe, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi, Vasily Kandinsky, and Francis Picabia. -

THE AMERICAN ART-1 Corregido

THE AMERICAN ART: AN INTRODUCTION Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection Paris-Boston, April 2011 SOMMARY INTRODUCTION 3 18th CENTURY 5 19th CENTURY 6 20th CENTURY 8 AMERICAN REALISM 8 ASHCAN SCHOOL 9 AMERICAN MODERNISM 9 MODERNIST PAINTING 13 THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST 14 HARLEM RENAISSANCE 14 NEW DEAL ART 14 ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 15 ACTION PAINTING 18 COLOR FIELD 19 POLLOCK AND ABSTRACT INFLUENCES 20 ART CRITICS OF THE POST-WORLD WAR II ERA 21 AFTER ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 23 OTHER MODERN AMERICAN MOVEMENTS 24 THE GELONCH VILADEGUT COLLECTION 2 http://www.gelonchviladegut.com The vitality and the international presence of a big country can also be measured in the field of culture. This is why Statesmen, and more generally the leaders, always have the objective and concern to leave for posterity or to strengthen big cultural institutions. As proof of this we can quote, as examples, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the British Museum, the Monastery of Escorial or the many American Presidential Libraries which honor the memory of the various Presidents of the United States. Since the Holy Roman Empire and, notably, in Europe during the Renaissance times cultural sponsorship has been increasingly active for the sake of art or for the sense of splendor. Nowadays, if there is a country where sponsors have a constant and decisive presence in the world of the art, this is certainly the United States. Names given to museum rooms in memory of devoted sponsors, as well as labels next to the paintings noting the donor’s name, are a very visible aspect of cultural sponsorship, especially in America. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Plastic Dynamism in Pastel Modernism: Joseph Stella's

PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION by MEREDITH LEIGH MASSAR Bachelor of Arts, 2007 Baylor University Waco, Texas Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Fine Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 ! ""! PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION Thesis approved: ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Major Professor ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Frances Colpitt ___________________________________________________________________________ Rebecca Lawton, Curator, Amon Carter Museum ___________________________________________________________________________ H. Joseph Butler, Graduate Studies Representative For the College of Fine Arts ! """! Copyright © 2009 by Meredith Massar. All rights reserved ! "#! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to all those who have assisted me throughout my graduate studies at Texas Christian University. Thank you to my professors at both TCU and Baylor who have imparted knowledge and guidance with great enthusiasm to me and demonstrated the academic excellence that I hope to emulate in my future career. In particular I would like to recognize Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite for his invaluable help and direction with this thesis and the entire graduate school experience. Many thanks also to Dr. Frances Colpitt and Rebecca Lawton for their wisdom, suggestions, and service on my thesis committee. Thank you to Chris for the constant patience, understanding, and peace given throughout this entire process. To Adrianna, Sarah, Coleen, and Martha, you all have truly made this experience a joy for me. I consider myself lucky to have gone through this with all of you. Thank you to my brothers, Matt and Patrick, for providing me with an unending supply of laughter and support. -

The Logic of Modernism Author(S): Adrian Piper Source: Callaloo, Vol

The Logic of Modernism Author(s): Adrian Piper Source: Callaloo, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Summer, 1993), pp. 574-578 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2932257 . Accessed: 15/09/2011 20:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Callaloo. http://www.jstor.org THE LOGIC OF MODERNISM* ByAdrian Piper There are four interrelated properties of Euroethnic art that are central to understand- ing the development of modernism, and in particular the development of contemporary art in the United States within the last few decades: 1) its appropriative character;2) its formalism; 3) its self-awareness; and 4) its commitment to social content. These four properties furnish strong conceptual and strategic continuities between the history of European art-modernism in particular-and recent developments in American art with explicitly political subject matter. Relative to these lines of continuity, the peculiarly American variety of modernism known as Greenbergian formalism is an aberration. Characterized by its repudiation of content in general and explicitly political subject matter in particular, Greenbergian formalism gained currency as an opportunistic ideo- logical evasion of the threat of cold war McCarthyite censorship and red-baiting in the fifties. -

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project)

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project) Michael Hoctor Keywords: Paul Gauguin Mark Rothko Pablo Picasso Jackson Pollock Synchromy Peggy Guggenheim Armory Show Collage Abstract expressionism Color Field Painting Action Painting MODERN ABSTRACT ART Part Three This article will conclude with a class lesson to help students appreciate and better understand art without narrative. The class will produce a 20th-Century Abstract Art Project, with an optional step into 21st Century Digital Art. REALISM ABSTRACTION DIVIDE This article skips a small rock across a large body of well-documented art history, including 650,000 books covering fine art that are currently available, as well as approximately 55,000 on critical insights, and almost 15,000 books examining the methods of individual artists and how they approached their work. You, of course can read a lot of them in your spare time! But today, our goal is to is gain a better understanding of why, at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was a major departure in how some groups of "avant-garde" painters approached their canvas, abandoning realistic art. The rock's trajectory attempts to show how the camera's extraordinary technology provoked some phenomenal artists to re- examine how they painted, inventing new methods of applying colors in a far less photographic manner that was far more subjective, departing from: what we see to focus on what way we see. 2 These innovators produced art that in time became incredibly valued. -

Rayonists and Futurists: a Manifesto, 1913

MIKHAIL LARIONOV AND NATALYA GONCHAROVA Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 For biographies see pp. 79 and 54. The text of this piece, "Luchisty i budushchniki. Manifest," appeared in the miscel- lany Oslinyi kkvost i mishen [Donkey's Tail and Target] (Moscow, July iQn), pp. 9-48 [bibl. R319; it is reprinted in bibl. R14, pp. 175-78. It has been translated into French in bibl. 132, pp. 29-32, and in part, into English in bibl. 45, pp. 124-26]. The declarations are similar to those advanced in the catalogue of the '^Target'.' exhibition held in Moscow in March IQIT fbibl. R315], and the concluding para- graphs are virtually the same as those of Larionov's "Rayonist Painting.'1 Although the theory of rayonist painting was known already, the "Target" acted as tReTormaL demonstration of its practical "acKieveffllBnty' Becau'S^r^ffie^anous allusions to the Knave of Diamonds. "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," and David Burliuk, this manifesto acts as a polemical гейроп^ ^Х^ШШУ's rivals^ The use of the Russian neologism ШШ^сТиШ?, and not the European borrowing futuristy, betrays Larionov's current rejection of the West and his orientation toward Russian and East- ern cultural traditions. In addition to Larionov and Goncharova, the signers of the manifesto were Timofei Bogomazov (a sergeant-major and amateur painter whom Larionov had befriended during his military service—no relative of the artist Alek- sandr Bogomazov) and the artists Morits Fabri, Ivan Larionov (brother of Mikhail), Mikhail Le-Dantiyu, Vyacheslav Levkievsky, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romano- vich, Aleksandr Shevchenko, and Kirill Zdanevich (brother of Ilya).