THE AMERICAN ART-1 Corregido

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery-Guide-Off-Kilter For-Web.Pdf

Dave Yust, Circular Composition (#11 Round), 1969 UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS 1400 Remington Street, Fort Collins, CO artmuseum.colostate.edu [email protected] | (970) 491-1989 TUES - SAT | 10 A.M.- 6 P.M. THURSDAY OPEN UNTIL 7:30 P.M. ALWAYS FREE OFF KILTER, ON POINT ART OF THE 1960s FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION ABOUT THE COLLECTION Drawing on the museum’s longstanding strength in 20th-century art of the United States and Europe and including long-time visitor favorites and recent acquisitions, Off Kilter, On Point: Art of the 1960s from the Permanent Collection highlights the depth and breadth of artworks in the museum permanent collection. The exhibition showcases a wide range of media and styles, from abstraction to pop, presenting novel juxtapositions that reflect the tumult and innovations of their time. The 1960s marked a time of undeniable turbulence and strife, but also a period of remarkable cultural and societal change. The decade saw the civil rights movement and the Civil Rights Act, the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam conflict, political assassinations, the moon landing, the first televised presidential debate, “The Pill,” and, arguably, a more rapid rate of technological advancement and cultural change than ever before. The accelerated pace of change was well reflected in the art of the time, where styles and movements were almost constantly established, often in reaction to one another. This exhibition presents most of the major stylistic trends of art of the 1960s in the United States and Europe, drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. An art collection began taking shape at CSU long before there was an art museum, and art of the 1960s was an early focus. -

Impersonality and the Cultural Work of Modernist Aesthetics Heather Arvidson a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Impersonality and the Cultural Work of Modernist Aesthetics Heather Arvidson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Jessica Burstein, Chair Carolyn Allen Gillian Harkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 Heather Arvidson University of Washington Abstract Impersonality and the Cultural Work of Modernist Aesthetics Heather Arvidson Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Jessica Burstein English Department This dissertation reanimates the multiple cultural and aesthetic debates that converged on the word impersonality in the first decades of the twentieth century, arguing that the term far exceeds the domain of high modernist aesthetics to which literary studies has consigned it. Although British and American writers of the 1920s and 1930s produced a substantial body of commentary on the unprecedented consolidation of impersonal structures of authority, social organization, and technological mediation of the period, the legacy of impersonality as an emergent cultural concept has been confined to the aesthetic innovations of a narrow set of writers. “Impersonality and the Cultural Work of Modernist Aesthetics” offers a corrective to this narrative, beginning with the claim that as human individuality seemed to become increasingly abstracted from urban life, the words impersonal and impersonality acquired significant discursive force, appearing in a range of publication types with marked regularity and emphasis but disputed valence and multiple meanings. In this context impersonality came to denote modernism’s characteristically dispassionate tone and fragmented or abstract forms, yet it also participated in a broader field of contemporaneous debate about the status of personhood, individualism, personality, and personal life. -

March 3-9, 2017 Books/Talks Santa Fe Ukulele Social Club Events ¡Chispa! at El Mesón Jordan Flaherty Thebeestrobistro, 101 W

CALENDAR LISTING GUIDELINES •Tolist an eventinPasa Week,sendanemail or press release to [email protected] or [email protected]. •Send material no less than twoweeks prior to the desired publication date. •For each event, provide the following information: time,day,date, venue/address,ticket prices,web address,phone number,and brief description of event(15 to 20 words). •All submissions arewelcome; however, events areincluded in Pasa Week as spaceallows. Thereisnocharge forlistings. • Returnofphotos and other materialscannot be guaranteed. • Pasatiempo reserves the righttopublish received information and photographs on The NewMexican's website. ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR •Toadd your eventtoThe New Mexican online calendar,visit santafenewmexican.com and click on the Calendar tab. March3-9,2017 •For further information contactPamela Beach: [email protected], 202 E. MarcySt., Santa Fe,NM87501, phone: 505-986-3019. CALENDAR COMPILED BYPAMELABEACH FRIDAY 3/3 available,505-988-1234, ticketssantafe.org, Saturdayencore. Galleryand Museum Openings Enfrascada AdobeGallery Teatro Paraguas Studio,3205 Calle Marie, 505-424-1601 221 Canyon Rd., 505-955-0550 Teatro Paraguas presents acomedy by playwright ACenturyofSan Ildefonso Painters: 1900-1999; TanyaSaracho,7:30 p.m., $12 and $20, enfrascada reception 5-7 p.m.; through April. .brownpapertickets.com, Thursdays-Sundays Axle Contemporary through March12. Look forthe mobile galleryinfront of the New Mexico Spring IntoMotion Museum of Art, 107W.PalaceAve. National DanceInstituteNew MexicoDanceBarns, Physical,mixed-media installation by Kathamann; 1140 Alto St. reception 5-7 p.m. Visit axleart.com forvan Astudentproduction, 7p.m., $10 and $15, locations through March26. ndi-nm.org, 505-983-7661. Back PewGallery UnnecessaryFarce First Presbyterian Church of SantaFe, 108 GrantAve., SantaFePlayhouse,142 E. -

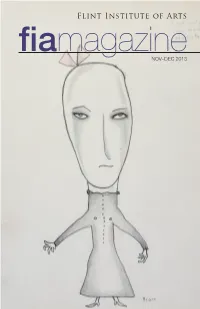

2013 Issue #5

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineNOV–DEC 2013 Website www.flintarts.org Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. contents Flint, MI 48503 Telephone 810.234.1695 from the director 2 Fax 810.234.1692 Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p exhibitions 3–4 Gallery Hours Mon–Wed & Fri, 12p–5p Thu, 12p–9p video gallery 5 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art on loan 6 Closed on major holidays Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p featured acquisition 7 Sun, 2p acquisitions 8 Museum Shop 810.234.1695 Mon–Wed, Fri & Sat, 10a–5p Thu, 10a–9p films 9–10 Sun, 1p–5p calendar 11 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Wed & Fri, 9a–5p Thu, 9a–9p news & programs 12–17 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art school 18–19 The Museum Shop and education 20–23 The Palette are open late for select special events. membership 24–27 Founders Art Sales 810.237.7321 & Rental Gallery Tue–Sat, 10a–5p contributions 28–30 Sun, 1p–5p or by appointment art sales & rental gallery 31 Admission to FIA members .............FREE founders travel 32 Temporary Adults .........................$7.00 Exhibitions 12 & under .................FREE museum shop 33 Students w/ ID ...........$5.00 Senior citizens 62+ ....$5.00 cover image From the exhibition Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada Beatrice Wood American, 1893–1998 I Eat Only Soy Bean Products pencil, color pencil on paper, 1933 12.0625 x 9 inches Gift of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC, 2011.370 FROM THE DIRECTOR 2 I never tire of walking through the sacred or profane, that further FIA’s permanent collection galleries enhances the action in each scene. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks COMPARATIVE LITERATURE/228 JONATHAN MAYHEW Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett for John Kronik, in memoriam, “il miglior fabbro” HAT DOES IT MEAN to be a modernist poet at the end of the twentieth Wcentury? Perhaps no poet more clearly embodies the ethos of “late mod- ernism” than José Angel Valente, whose final book, Fragmentos de un libro futuro, was published after his death in the final year of the millennium. This book is not only posthumous but also designed to be posthumous. According to its front flap, “José Angel Valente concibió una suerte de obra poética ‘abierta’, un libro que—como la parábola cervantina de Ginés de Pasamonte o la novela de Proust —no acabaría sino con la desaparición misma del autor” ( José Angel Valente conceived of a sort of “open” poetic work, a book that, like the Cervantine para- bole of Ginés de Pasamonte or Proust’s novel, would not end until the author himself disappeared; my translation here and throughout). The book’s futurity, then, lies beyond the lifespan of the poet. Yet, in relation to the avant-garde movements of the earlier part of the twentieth century, Valente’s book is decid- edly nostalgic rather than forward looking. Its predominant tone is elegiac. While steeped in the culture of modernity, it ultimately exemplifies an arrière-garde rather than an avant-garde spirit. Given Valente’s pre-eminent position within the canon of late twentieth-century Spanish poetry, an examination of his work during the last two decades of his life can also reveal the degree to which the modernist aesthetic has maintained its vitality in the contemporary period. -

Center Bridge Burning

Burning of Center Bridge, 1923 Edward W. Redfield (1869-1965 oil on canvas H. 50.25 x W 56.25 inches James A. Michener Art Museum, acquired with funds secured by State Senator Joe Conti, and gifts from Joseph and Anne Gardocki, and the Laurent Redfield Family Biography The Pennsylvania school born in the Academy at Philadelphia or in the person of Edward W. Redfield is a very concise expression of the simplicity of our language and of the prosaic nature of our sight. It is democratic painting—broad, without subtlety, vigorous in language if not absolutely in heart, blatantly obvious or honest in feeling. It is an unbiased, which means, inartistic, record of nature. —Guy Pene du Bois Among the New Hope impressionists, Edward Willis Redfield was the most decorated, winning more awards than any other American artist except John Singer Sargent. Primarily a landscape painter, Redfield was acclaimed as the most “American” artist of the New Hope school because of his vigor and individualism. Redfield favored the technique of painting en plein air, that is, outdoors amid nature. Tying his canvas to a tree, Redfield worked in even the most brutal weather. Painting rapidly, in thick, broad brushstrokes, and without attempting preliminary sketches, Redfield typically completed his paintings in one sitting. Although Redfield is best known for his snow scenes, he painted several spring and summer landscapes, often set in Maine, where he spent his summers. He also painted cityscapes, including, most notably, Between Daylight and Darkness (1909), an almost surreal, tonalist painting of the New York skyline in twilight. -

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project)

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project) Michael Hoctor Keywords: Paul Gauguin Mark Rothko Pablo Picasso Jackson Pollock Synchromy Peggy Guggenheim Armory Show Collage Abstract expressionism Color Field Painting Action Painting MODERN ABSTRACT ART Part Three This article will conclude with a class lesson to help students appreciate and better understand art without narrative. The class will produce a 20th-Century Abstract Art Project, with an optional step into 21st Century Digital Art. REALISM ABSTRACTION DIVIDE This article skips a small rock across a large body of well-documented art history, including 650,000 books covering fine art that are currently available, as well as approximately 55,000 on critical insights, and almost 15,000 books examining the methods of individual artists and how they approached their work. You, of course can read a lot of them in your spare time! But today, our goal is to is gain a better understanding of why, at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was a major departure in how some groups of "avant-garde" painters approached their canvas, abandoning realistic art. The rock's trajectory attempts to show how the camera's extraordinary technology provoked some phenomenal artists to re- examine how they painted, inventing new methods of applying colors in a far less photographic manner that was far more subjective, departing from: what we see to focus on what way we see. 2 These innovators produced art that in time became incredibly valued. -

Stanton Macdonald-Wright: Homage to Color for Immediate Release: July 30, 2013

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] Stanton Macdonald-Wright: Homage to Color For immediate release: July 30, 2013 Peyton Wright Gallery is pleased to announce “Stanton Macdonald-Wright: Homage to Color” The exhibition commences with an artist’s reception on Friday, September 6th, 2013 from 5:00 to 8:00 p.m., and continues through October 2nd, 2013. Peyton Wright Gallery is pleased to announce the second major exhibition of works by Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1890-1973). One of America's leading modernist painters and an early and prolific champion of abstract art, Macdonald- Wright moved to Paris as a teenager and founded the avant-garde painting movement Synchromism in 1912 with Morgan Russell. Often considered the first American abstract art style, the movement was described by Macdonald- Wright as follows: “Synchromism simply means ‘with color’ as symphony means ‘with sound’, and our idea was to produce an art whose genesis lay not in objectivity, but in form produced in color.” Macdonald-Wright and Russell wrote Treatise on Arrival Return of the Astronauts, 1965, oil on Color in 1924 to further panel, 72 x 42 inches; 73 x 43 inches framed. explain Synchromism. The book postulated that color and sound are exact and literal equivalents of each other, wherein color is responsive to and reflective of mood and thought; musical tones have corresponding hues, wherein warm colors translate to outward, convex surfaces and cool colors indicate areas of compositional repose, much like the way a break functions in a piece of music. -

American Impressionism Treasures from the Daywood Collection

American Impressionism Treasures from the Daywood Collection American Impressionism: Treasures from the Daywood Collection | 1 Traveling Exhibition Service The Art of Patronage American Paintings from the Daywood Collection merican Impressionism: Treasures from the Daywood dealers of the time, such as Macbeth Gallery in New York. Collection presents forty-one American paintings In 1951, three years after Arthur’s death, Ruth Dayton opened A from the Huntington Museum of Art in West Virginia. the Daywood Art Gallery in Lewisburg, West Virginia, as a The Daywood Collection is named for its original owners, memorial to her late husband and his lifelong pursuit of great Arthur Dayton and Ruth Woods Dayton (whose family works of art. In doing so, she spoke of her desire to “give surnames combine to form the moniker “Daywood”), joy” to visitors by sharing the collection she and Arthur had prominent West Virginia art collectors who in the early built with such diligence and passion over thirty years. In twentieth century amassed over 200 works of art, 80 of them 1966, to ensure that the collection would remain intact and oil paintings. Born into wealthy, socially prominent families on public display even after her own death, Mrs. Dayton and raised with a strong appreciation for the arts, Arthur and deeded the majority of the works in the Daywood Art Gallery Ruth were aficionados of fine paintings who shared a special to the Huntington Museum of Art, West Virginia’s largest admiration for American artists. Their pleasure in collecting art museum. A substantial gift of funds from the Doherty only increased after they married in 1916. -

Fine Art, Pop Art, Photographs: Day 1 of 3 Friday – September 27Th, 2019

Stanford Auctioneers Fine Art, Pop Art, Photographs: Day 1 of 3 Friday – September 27th, 2019 www.stanfordauctioneers.com | [email protected] 1: RUDOLF KOPPITZ - Zwei Bruder USD 1,200 - 1,500 Rudolf Koppitz (Czech/Austrian, 1884-1936). "Zwei Bruder [Two Brothers]". Original vintage photometalgraph. c1930. Printed 1936. Stamped with the photographer's name, verso. Edition unknown, probably very small. High-quality archival paper. Ample margins. Very fine printing quality. Very good to fine condition. Image size: 8 1/8 x 7 7/8 in. (206 x 200 mm). Authorized and supervised by Koppitz shortly before his death in 1936. [25832-2-800] 2: CLEMENTINE HUNTER - Zinnias in a Blue Pot USD 3,500 - 4,000 Clementine Hunter (American, 1886/1887-1988). "Zinnias in a Blue Pot". Gouache on paper. c1973. Signed lower right. Very good to fine condition; would be fine save a few very small paint spots, upper rght. Overall size: 15 3/8 x 11 3/4 in. (391 x 298 mm). Clementine Reuben Hunter, a self-taught African-American folk artist, was born at Hidden Hill, a cotton plantation close to Cloutierville, Louisiana. When she was 14 she moved to the Melrose Plantation in Cane River County. She is often referred to as "the black Grandma Moses." Her works in gouache are rare. The last auction record of her work in that medium that we could find was "Untitled," sold for $3,000 at Sotheby's New York, 12/19/2003, lot 1029. [29827-3-2400] 3: PAUL KLEE - Zerstoerung und Hoffnung USD 800 - 1,000 Paul Klee (Swiss/German, 1879 - 1940).