Impersonality and the Cultural Work of Modernist Aesthetics Heather Arvidson a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN ART-1 Corregido

THE AMERICAN ART: AN INTRODUCTION Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection Paris-Boston, April 2011 SOMMARY INTRODUCTION 3 18th CENTURY 5 19th CENTURY 6 20th CENTURY 8 AMERICAN REALISM 8 ASHCAN SCHOOL 9 AMERICAN MODERNISM 9 MODERNIST PAINTING 13 THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST 14 HARLEM RENAISSANCE 14 NEW DEAL ART 14 ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 15 ACTION PAINTING 18 COLOR FIELD 19 POLLOCK AND ABSTRACT INFLUENCES 20 ART CRITICS OF THE POST-WORLD WAR II ERA 21 AFTER ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 23 OTHER MODERN AMERICAN MOVEMENTS 24 THE GELONCH VILADEGUT COLLECTION 2 http://www.gelonchviladegut.com The vitality and the international presence of a big country can also be measured in the field of culture. This is why Statesmen, and more generally the leaders, always have the objective and concern to leave for posterity or to strengthen big cultural institutions. As proof of this we can quote, as examples, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the British Museum, the Monastery of Escorial or the many American Presidential Libraries which honor the memory of the various Presidents of the United States. Since the Holy Roman Empire and, notably, in Europe during the Renaissance times cultural sponsorship has been increasingly active for the sake of art or for the sense of splendor. Nowadays, if there is a country where sponsors have a constant and decisive presence in the world of the art, this is certainly the United States. Names given to museum rooms in memory of devoted sponsors, as well as labels next to the paintings noting the donor’s name, are a very visible aspect of cultural sponsorship, especially in America. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks COMPARATIVE LITERATURE/228 JONATHAN MAYHEW Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett for John Kronik, in memoriam, “il miglior fabbro” HAT DOES IT MEAN to be a modernist poet at the end of the twentieth Wcentury? Perhaps no poet more clearly embodies the ethos of “late mod- ernism” than José Angel Valente, whose final book, Fragmentos de un libro futuro, was published after his death in the final year of the millennium. This book is not only posthumous but also designed to be posthumous. According to its front flap, “José Angel Valente concibió una suerte de obra poética ‘abierta’, un libro que—como la parábola cervantina de Ginés de Pasamonte o la novela de Proust —no acabaría sino con la desaparición misma del autor” ( José Angel Valente conceived of a sort of “open” poetic work, a book that, like the Cervantine para- bole of Ginés de Pasamonte or Proust’s novel, would not end until the author himself disappeared; my translation here and throughout). The book’s futurity, then, lies beyond the lifespan of the poet. Yet, in relation to the avant-garde movements of the earlier part of the twentieth century, Valente’s book is decid- edly nostalgic rather than forward looking. Its predominant tone is elegiac. While steeped in the culture of modernity, it ultimately exemplifies an arrière-garde rather than an avant-garde spirit. Given Valente’s pre-eminent position within the canon of late twentieth-century Spanish poetry, an examination of his work during the last two decades of his life can also reveal the degree to which the modernist aesthetic has maintained its vitality in the contemporary period. -

The “Knockings and Batterings” Within: Late Modernism’S

THE “KNOCKINGS AND BATTERINGS” WITHIN: LATE MODERNISM’S REANIMATIONS OF NARRATIVE FORM by JENNIFER E. NOYCE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jennifer E. Noyce Title: The “Knockings and Batterings” Within: Late Modernism’s Reanimations of Narrative Form This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Mark Quigley Chair Paul Peppis Core Member Helen Southworth Core Member Randall McGowen Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2014 ii © 2014 Jennifer Noyce iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jennifer E. Noyce Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2014 Title: The “Knockings and Batterings” Within: Late Modernism’s Reanimations of Narrative Form This dissertation corrects the notion that fiction written in the late 1920s through the early 1940s fails to achieve the mastery and innovation of high modernism. It posits late modernism as a literary dispensation that instead pushes beyond high modernism’s narrative innovations in order to fully express individuals’ lived experience in the era between world wars. This dissertation claims novels by Elizabeth Bowen, Evelyn Waugh, and Samuel Beckett, as exemplars of a late modernism characterized by invocation and redeployment of conventionalized narrative forms in service of fresh explorations of the dislocation, inauthenticity, and alienation that characterize this era. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

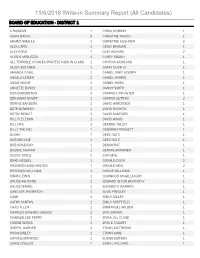

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

GEORGE RICHARDS MINOT December 2, 1885-February 25, 1950

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES G EORGE RICHARDS M INOT 1885—1950 A Biographical Memoir by W . B . C ASTLE Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1974 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. i GEORGE RICHARDS MINOT December 2, 1885-February 25, 1950 BY W. B. CASTLE EORGE MINOT was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on Decem- G ber 2, 1885, the eldest of three sons of Dr. James Jackson and Elizabeth Frances (Whitney) Minot. His ancestors had been successful in business and professional careers in Boston. His father was a private practitioner and for many years a clinical teacher of medicine as a member of the staff of the Massachusetts General Hospital. In the second half of the nineteenth century his great uncle, Francis Minot, became the third Hersey Pro- fessor of the Theory and Practice of Physic at Harvard; and his cousin, Charles Sedgwick Minot, a distinguished anatomist, was Professor of Histology there in the early years of the twentieth century. George Minot's grandmother was the daughter of Dr. James Jackson, the second Hersey Professor and a cofounder with John Collins Warren of the Massachusetts General Hos- pital, which opened its doors in 1821. Thus his forebears, like those of other Boston medical families, were influential par- ticipants in the activities of the Harvard Medical School and its affiliated teaching hospital. George was regarded by his physician-father as a delicate child who required physical protection and nourishing food. -

Hubert M. Sedgwick

HUBERT M. SEDGWICK A SEDGWICK GENEALOGY DESCENDANTS OF DEACON BENJAMIN SEDGWICK Compiled by Hubert M. Sedgwick New Haven Colony Historical Society 114 Whitney Avenue New Haven, Connecticut 1961 This book was composed and manufactured for the New Haven Colony Historical Society by The Shoe String Press, Inc. , Hamden, Connecticut, United States of America. CONTENTS The Sedgwick Family - a Chart vii Introduction ix The Numbering Code - an Explanation xi Deacon Benjamin Sedgwick - (B) 3 The Descendants of Benjamin Sedgwick Bl Sarah Sedgwick Gold 9 B2 John Sedgwick .53 B3 Benjamin Sedgwick Jr. 147 B4 Theodore Sedgwick 167 B5 Mary Ann Sedgwick Swift 264 B6 Lorain (Laura) Sedgwick Parsons 310 Index 315 THE-SEDGWICK FAMILY 1st ROBERT SEDGWICK, of London, England, son of William Gen. Sedgwicke, of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England; baptised at Woburn, May 6, 1613; married Joanna Blake, of Andover, England, emigrated to Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1635-6; became merchant at Charlestown and Boston; member of General Court; built first fort at Boston; first Major General of Massachusetts Bay Colony; died Jamaica, West Indies, May 24, 1656. 2nd WILLIAM SEDGWICK, 2nd son of Major General Robert, Gen. born 1643; married Elizabeth Stone, daughter of Reverend Samuel Stone, of Hartford, Connecticut; died 1674. 3rd CAPTAIN SAMUEL SEDGWICK, only son of William, born Gen. 1667; married Mary Hopkins, of Hartford; lived at West Hartford, Connecticut; died 173 5. They had eleven children, of whom we trace the descendants of the eleventh, BENJAMIN. 4th 1. Samuel, Jr. '7. Mary 1705-1759 Gen. 1690-1725 - 2. Jonathan 8. Elizabeth 1693-1771 1708-1738 3. Ebenezer 9. -

ED427369.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 369 CS 510 003 AUTHOR Whitney, Shawnlee A., Ed. TITLE National Developmental Conference on Individual Events Addressing Individual Events, NFA Lincoln-Douglas Debate, and NPDA Parliamentary Debate Conference Proceedings (3rd, Houston, Texas, August 13-16, 1997). PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 224p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Debate; *Debate Format; Higher Education; Oral Interpretation; Persuasive Discourse IDENTIFIERS *Debate Coaches; *Debate Tournaments; Individual Events (Forensics); National Parliamentary Debate Association ABSTRACT This proceedings presents 19 papers delivered a National Developmental Conference on Individual Events, addressing individual events, Lincoln-Douglas debate, and parliamentary debate. After presenting the conference schedule, the list of attendees, and resolutions, papers in the proceedings are: "The Ghostwriter, The Laissez-Faire Coach, and the Forensic Professional: Negotiating the Overcoaching vs. Undercoaching Dilemma in Original Contest Speeches" (James J. Kimble); "Professionalism and Forensics: A Matter of Choice" (Larry Schnoor and Bryant K. Alexander); "Creating Space for the Physically Challenged Competitor in Individual Events" (David L. Kosloski); "Creating an Individual Events Judging Philosophy" (Jeff Przybylo); "Challenging the Conventions of Oral Interpretation" (Chris S. Aspdal); "Returning to Our Roots: A New Direction for Oral Interpretation" (Trischa Knapp); "Developing Functional Standards as a means -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

The BIOLOGICAL BULLETIN (67 Copies of the BIOLOGICAL BULLE- TIN Sent and While New Sub- Being Out) ; 19 by Gift, Only 30 Paid Scriptions Have Been Added

Vol. LV July 1928 No. i BIOLOGICAL BULLETIN THE MARINE BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY. THIRTIETH REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1927 FORTIETH YEAR. .1. TRUSTEES AND EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (AS OF AUGUST * 9> 1927) LIBRARY COMMITTEE 3 II. ACT OF INCORPORATION 3 III. BY-LAWS OF THE CORPORATION 4 IV. REPORT OF THE TREASURER 5 V. REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN 1 1 VI. REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR 17 Statement 17 Addenda : 1 . The Staff, 1927 27 2. Investigators and Students, 1927 30 3. Tabular View of Attendance 41 4. Subscribing and Cooperating Institutions, 1927 42 5. Evening Lectures, 1927 43 6. Members of the Corporation 44 I. TRUSTEES. EX OFFICIO. FRANK R. LILLIE, President of the Corporation, The University of Chicago. MERKEL H. JACOBS, Director, University of Pennsylvania. LAWRASON RIGGS, JR., Treasurer, 25 Broad Street, New York City. L. L. WOODRUFF, Clerk of the Corporation, and Secretary of the Board of Trustees pro tan, Yale University. EMERITUS. CORNELIA M. CLAPP, Mount Holyoke College. OILMAN A. DREW, Eagle Lake, Florida. TO SERVE UNTIL IQ3I. H. C. BUMPUS, Brown University. W. C. CURTIS, University of Missouri. 1 i 2 MARINE BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY. B. M. DUGGAR, University of Wisconsin. GEORGE T. MOORE, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis. W. J. V. OSTERHOUT, Member of the Rockefeller Institute for Med- ical Research. J. R. SCHRAMM, University of Pennsylvania. WILLIAM M. WHEELER, Bussey Institution, Harvard University. LORANDE L. WOODRUFF, Yale University. TO SERVE UNTIL I93O. E. G. CONKLIN, Princeton University. OTTO C. GLASER, Amherst College. Ross G. HARRISON, Yale University. H. S. JENNINGS, John Hopkins University. F. P. KNOWLTON, Syracuse University. -

Spring 2015 Commencement Program

COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER FOLSOM STADIUM MAY 9, 2015 One Hundred Thirty-Ninth Year of the University The Regents of the University of Colorado Dear Graduate: One of the greatest honors for the University of Colorado Board of Regents, the institution’s governing board, is to be part of a graduation ceremony. Your success is a success for us all. Your degree is a measure not only of an accom- plishment of dedication and talent, but also notice to the world that you have the intellectual gifts and discipline to contribute greatly to our community. Your commencement ceremony, like every University of Colorado graduation since 1935, will close with the reading of the timeless Norlin Charge. Today “marks your initiation in the fullest sense of the fellowship of the university, as bearers of her torch, as centers of her influence, as promoters of her spirit.” Each year, the University of Colorado grants thousands of bachelor’s, master’s, pro- fessional and doctoral degrees to some of the greatest minds in our country and the world. Today, we proudly add your name to this notable group of individuals. Congratulations on your hard-earned accomplishment. Sincerely, The Regents of Colorado Back Row: Glen Gallegos, District 3 (Grand Junction); Steve Bosley, At Large (Longmont); Stephen Ludwig, At Large (Denver); Michael Carrigan, District 1 (Denver); John Carson, District 6 (Highlands Ranch). Front Row: Linda Shoemaker, District 2 (Boulder); Kyle Hybl, Chairman, District 5 (Colorado Springs); Irene Griego, Vice Chair, District 7 (Lakewood); Sue Sharkey, District 4 (Castle Rock). 2 Dear Graduate, Congratulations, your hard work has brought you to this day.