Holy Moly Under the Terebinth Tree: a Response to My Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sea Scenarios

SEA SCENARIOS ellas is said to be a land of a thousand islands, so warbands Determine the Scenario: The player in the Sea realm rolls a d6. often must necessarily travel by sea in pursuit of their For each battle that the player has won since his warband has been Hgoals. A warband that has entered the realm of the Sea has at Sea, the player adds 1 to the result. If the player’s last battle was loaded their men, horses, and equipment into penteconters – small a loss, the player subtracts 1 from the total. The final result is the warships with a single sail and fifty oars. In these ships they sail the player’s Scenario: waters of the Middle Sea, travelling ever further from their homes 1. (or less) Fresh Water in the city-states of Hellas. Each Sea Scenario represents an en- 2. The Hostage counter on one of the islands where the warband stops to resupply, 3. Shipwrecked and some even contain valuable Clues to be found that will guide 4. Defend the Ship them closer to their goal. The Scenarios are organized by number, 5. Safe Passage with the lower numbers representing early encounters close to the 6. The Isle of Torment safe waters of home, and the higher numbers are distant, mysteri- 7. Isle of the Cyclopes ous islands with strange and dangerous inhabitants. 8. All Men Are Pigs 9. Isle of the Lotus Eaters The Beach: In practical terms, the main difference between Land 10. Beyond the Pillars of Heracles and Sea Scenarios is that the Sea Scenarios always take place next Once a player progresses to Scenario #10 and wins, the player’s to the ocean – one table edge will always represent a beach. -

The Function of Pantagruelion in Rabelais's Quart Livre

[Expositions 11.2 (2017) 1–33] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 The Function of Pantagruelion in Rabelais’s Quart Livre TIMOTHY HAGLUND Ashbrook Center at Ashland University ABSTRACT The praise of the famous Pantagruelion herb that occupies the last four chapters of Rabelais’s Tiers Livre bears on the narrative of the Quart Livre. Although apparently frivolous or superfluous, the use of Pantagruelion as a blow-tube places it in the same class of beings as the other physeter in Rabelais’s text—the whale that later appears in chapters 33 and 34 of the Quart Livre. Pantagruel’s preparedness for the whale, compared with the misplaced fear of Panurge and overconfidence of the Pantagruelic artillery, rests in part on his knowledge that physeters are governed by necessities, by natures. Connecting Pantagruelion to the whale in this way reveals an order in nature, one that requires belief despite appearances. Pantagruelion supplies or inspires such belief. Nature and the Pantagruelion Herb φύσις: origin, growth, nature, constitution φυσητήρ: a blowpipe or blowtube, the blowhole or spiracle of a whale Like many of Rabelais’s passages, the praise of Pantagruelion that closes the Tiers Livre has a generative capacity, encouraging interpretation. There Rabelais cryptically describes the plant to be brought on board in preparation for the search for the Dive Bouteille, which supposedly holds the final answer to Panurge’s marriage question, initially raised with the end of the war against the Dipsodians and the onset of political peace in the Tiers Livre. The plant’s qualities seem to have little to do with this quest. -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

Sex in the Ancient World from a to Z the Ancient World from a to Z

SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z What were the ancient fashions in men’s shoes? How did you cook a tunny or spice a dormouse? What was the daily wage of a Syracusan builder? What did Romans use for contraception? This new Routledge series will provide the answers to such questions, which are often overlooked by standard reference works. Volumes will cover key topics in ancient culture and society—from food, sex and sport to money, dress and domestic life. Each author will be an acknowledged expert in their field, offering readers vivid, immediate and academically sound insights into the fascinating details of daily life in antiquity. The main focus will be on Greece and Rome, though some volumes will also encompass Egypt and the Near East. The series will be suitable both as background for those studying classical subjects and as enjoyable reading for anyone with an interest in the ancient world. Already published: Food in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Dalby Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z Mark Golden Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z John G.Younger Forthcoming titles: Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z Geoffrey Arnott Money in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Meadows Domestic Life in the Ancient World from A to Z Ruth Westgate and Kate Gilliver Dress in the Ancient World from A to Z Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones et al. SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z John G.Younger LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006. -

MMF Companion Bulfinch Myths

Reading Greek and Roman Mythology The Myth Louis Made Markos, act PhD through Christian Eyes COMPANION FILE: BULFINCH’S MYTHOLOGY PDF Excerpts selected from Bulfinch’s Mythology: Complete In One Volume for use in conjunction with The Myth Made Fact arn wit Le h Louis Markos o n m o Cl .c assicalU The Myth Made Fact: Reading Greek and Roman Mythology through Christian Eyes Companion File: Bulfinch’s Mythology PDF All myths in this PDF are taken, unedited, from Bulfinch’s Mythology, Complete In One Volume by Thomas Bulfinch. Courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Illustrations courtesy of Adobe Stock artist Matias Del Carmine Design by David Gustafson Classical Academic Press 515 S. 32nd Street Camp Hill, PA 17011 www.ClassicalAcademicPress.com Reading 1 Daedalus Read this myth along with chapter 1 of The Myth Made Fact. he labyrinth from which Theseus escaped by them, astonished at the sight, and thinking they were gods means of the clew of Ariadne was built by Daeda- who could thus cleave the air. lus, a most skilful artificer. It was an edifice with T They passed Samos and Delos on the left and Lebynthos numberless winding passages and turnings opening into on the right, when the boy, exulting in his career, began to one another, and seeming to have neither beginning nor leave the guidance of his companion and soar upward as if end, like the river Maeander, which returns on itself, and to reach heaven. The nearness of the blazing sun softened flows now onward, now backward, in its course to the sea. -

Stories of the Ancient Greeks

Conditions and Terms of Use PREFACE Copyright © Heritage History 2009 The tales in this book are old; some of them, it may be, Some rights reserved are even older than we suppose. But there is always a new This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization generation to whom the ancient stories must be told; and the dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the author has spent pleasant hours in trying to retell some of them promotion of the works of traditional history authors. for the boys and girls of to-day. The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and He remembers what joy it was to him to read about the are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced Greek gods and heroes; and he knows that life has been brighter within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. to him ever since because of the knowledge thus gained and the The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are fancies thus kindled. It is his hope to brighten, if possible, other the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some young lives by repeating for them the immortal fictions and the restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity deathless histories which have been delivered to new audiences of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that for thousands of years. -

Pharmacies for Pain and Trauma in Ancient Greece

International Orthopaedics (2019) 43:1529–1536 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4219-x ORTHOPAEDIC HERITAGE Pharmacies for pain and trauma in ancient Greece Andreas F. Mavrogenis1 & Theodosis Saranteas2 & Konstantinos Markatos3 & Antonia Kotsiou4 & Christina Tesseromatis4 Received: 17 August 2018 /Accepted: 29 October 2018 /Published online: 9 November 2018 # SICOT aisbl 2018 Abstract Purpose To summarize pharmacies for pain and trauma in ancient Greece, to present several pharmaceutical/therapeutical methods reported in myths and ancient texts, and to theorize on the medical explanation upon which these pharmacies were used. Method A thorough literature search was undertaken in PubMed and Google Scholar as well as in physical books in libraries to summarize the pharmacies and pain practices used for trauma in ancient Greece. Results Archeological findings and historical texts have revealed that humans have always suffered from diseases and trauma that were initially managed and healed by priests and magicians. In early Greek antiquity, the term pharmacy was related to herbal inquiries, with the occupants called charmers and pharmacists. Additionally, apart from therapeutic methods, ancient Greeks acknowledged the importance of pain therapy and had invented certain remedies for both acute and chronic pain management. With observations and obtaining experience, they used plants, herbs, metals and soil as a therapeutic method, regardless of the cultural level of the population. They achieved sedation and central and peripheral analgesia with opium and cold, as well as relaxation of smooth muscle fibers and limiting secretions with atropina. Conclusion History showed a lot of experience obtained from empirical testing of pain treatment in ancient people. Experience and reasoning constructed an explanatory account of diseases, therapies and health and have provided for the epistemology of medicine. -

![[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7259/pdf-the-myths-and-legends-of-ancient-greece-and-rome-4397259.webp)

[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome

The Myths & Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome E. M. Berens p q xMetaLibriy Copyright c 2009 MetaLibri Text in public domain. Some rights reserved. Please note that although the text of this ebook is in the public domain, this pdf edition is a copyrighted publication. Downloading of this book for private use and official government purposes is permitted and encouraged. Commercial use is protected by international copyright. Reprinting and electronic or other means of reproduction of this ebook or any part thereof requires the authorization of the publisher. Please cite as: Berens, E.M. The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. (Ed. S.M.Soares). MetaLibri, October 13, 2009, v1.0p. MetaLibri http://metalibri.wikidot.com [email protected] Amsterdam October 13, 2009 Contents List of Figures .................................... viii Preface .......................................... xi Part I. — MYTHS Introduction ....................................... 2 FIRST DYNASTY — ORIGIN OF THE WORLD Uranus and G (Clus and Terra)........................ 5 SECOND DYNASTY Cronus (Saturn).................................... 8 Rhea (Ops)....................................... 11 Division of the World ................................ 12 Theories as to the Origin of Man ......................... 13 THIRD DYNASTY — OLYMPIAN DIVINITIES ZEUS (Jupiter).................................... 17 Hera (Juno)...................................... 27 Pallas-Athene (Minerva).............................. 32 Themis .......................................... 37 Hestia -

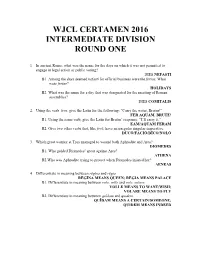

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Intermediate Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. In ancient Rome, what was the name for the days on which it was not permitted to engage in legal action or public voting? DIES NEFASTI B1. Among the days deemed nefasti for official business were the feriae. What were feriae? HOLIDAYS B2. What was the name for a day that was designated for the meeting of Roman assemblies? DIES COMITALIS 2. Using the verb fero, give the Latin for the following: “Carry the water, Brutus!” FER AQUAM, BRUTE! B1. Using the same verb, give the Latin for Brutus’ response: “I’ll carry it.” EAM/AQUAM FERAM B2. Give two other verbs that, like ferō, have an irregular singular imperative. DUCŌ/FACIŌ/DĪCO/NOLŌ 3. Which great warrior at Troy managed to wound both Aphrodite and Ares? DIOMEDES B1. Who guided Diomedes’ spear against Ares? ATHENA B2.Who was Aphrodite trying to protect when Diomedes injured her? AENEAS 4. Differentiate in meaning between rēgīna and rēgia. RĒGĪNA MEANS QUEEN; RĒGIA MEANS PALACE B1. Differentiate in meaning between volo, velle and volo, volare. VOLLE MEANS TO WANT/WISH; VOLARE MEANS TO FLY B2. Differentiate in meaning between quīdam and quidem. QUĪDAM MEANS A CERTAIN/SOMEONE; QUIDEM MEANS INDEED 5. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “I was sleeping under the tree.” DORMIĒBAM SUB ARBORE B1. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “Who spoke before you?” QUIS ANTE TĒ DĪXIT/DICĒBAT B2. Translate the following sentence into Latin using a participle: “I hear you singing.” AUDIŌ TĒ CANENTEM/CANTANTEM 6. At which battle of 202 BCE did Scipio Africanus achieve final victory over Hannibal, bringing an end to the Second Punic War? ZAMA B1. -

Bulfinch's Mythology the Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

1 BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE BY THOMAS BULFINCH Table of Contents PUBLISHERS' PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 7 ROMAN DIVINITIES ............................................................................................................................ 16 PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA ............................................................................................................ 18 APOLLO AND DAPHNE--PYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS ............................ 24 JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTO--DIANA AND ACTAEON--LATONA AND THE RUSTICS .................................................................................................................................................... 32 PHAETON .................................................................................................................................................. 41 MIDAS--BAUCIS AND PHILEMON ....................................................................................................... 48 PROSERPINE--GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA ............................................................................................. 53 PYGMALION--DRYOPE-VENUS -

21-29 the CHARACTER of CIRCE in the ODYSSEY JD Mcclymont

http://akroterion.journals.ac.za THE CHARACTER OF CIRCE IN THE ODYSSEY J D McClymont (University of Zimbabwe) The article describes the character of Circe in the Odyssey, emphasizing that she has not only an evil but a positive side to her character. The implications of her being a witch, swearing an oath to Odysseus and being a god are explored. She is also briefly compared with other characters in the Odyssey. One of the most noteworthy incidents in the Odyssey is the visit of Odysseus to Aeaea, where the enchantress Circe turns his crewmen to animals. Circe is the most well-known witch-figure in Greek mythology, and indicates an early presence of belief in magic in classical literature. As an enchantress, however, she is not merely a special effect in a heroic story. There is more to her than meets the eye. There is an overly simple image of Circe as a typical example of witchcraft, which we can trace in Perkins’ Discourse on the Damned Art of Witchcraft. For this seventeenth century author, Circe is viewed as a historical example of the sort of black witch in which he believed (Anglo 1977:10), and this “evil-witch” idea certainly has precedent in classical literature, if we consider the story of Meroe in Apuleius as a malevolent figure, who turns Aristomenes into an animal (Frangoulidis 1999:381). There is a certain sexual overtone to Apuleius’ story – Aristomenes watches or looks on the woman and becomes an animal; and we may expect Circe’s transformation of men into animals to have a similar significance. -

The Snowdrop (Galanthus Nivalis): from Odysseus to Alzheimer

HISTORY THE SNOWDROP (GALANTHUS NIVALIS): FROM ODYSSEUS TO ALZHEIMER M.R. Lee* INTRODUCTION The author Robert Graves, in his work on Greek mythology published some years ago, suggested that such myths embodied folk memories of ancient knowledge.1 For this reason, if no other, they deserve our serious consideration. In this article, I hope to develop that proposal in relation to the snowdrop and Odysseus’ encounter with the enchantress Circe. Since early Greek times there has been a desultory interest in the snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) for the treatment of pain and other neurological disorders. About 30 years ago, an active principle galanthamine was extracted from the plant and subsequently synthesised. This development quickened interest markedly and has led to studies with the compound in Alzheimer’s disease. THE PLANT (GALANTHUS NIVALIS) The common name for Galanthus nivalis, the snowdrop, appears to be derived from Germany in the sixteenth century where the flower was thought to resemble an earring or pendant (Schneetropf). The generic name Galanthus comes from the Greek gala (milk) and anthos (flower) and refers to the milk-white flower (Figure 1). The genus comprises some 12 species of small perennial bulbous herbs.2 The leaves are linear (or elliptical) and the flowers solitary and nodding. Originating in Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus, the plant was probably introduced into Great Britain in the early FIGURE 1 medieval period by religious communities and has naturalised The snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis). widely (see below).3 One species is named after the British naturalist Elwes and another after the distinguished physiologist Sir Michael Foster.2 Dunwich in Suffolk (the Greyfriars) and Brinkburn Priory The common snowdrop Galanthus nivalis has narrow at Rothbury in Northumberland.