Constraints on the Adult-Offspring Size Relationship in Protists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy, Nomenclature, and Evolution of the Early Schubertellid Fusulinids Vladimir I

Boise State University ScholarWorks Geosciences Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Geosciences 3-1-2011 Taxonomy, Nomenclature, and Evolution of the Early Schubertellid Fusulinids Vladimir I. Davydov Boise State University This document was originally published by Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Copyright restrictions may apply. DOI: 10.4202/app.2010.0026 Taxonomy, nomenclature, and evolution of the early schubertellid fusulinids VLADIMIR I. DAVYDOV Davydov, V.I. 2011. Taxonomy, nomenclature, and evolution of the early schubertellid fusulinids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56 (1): 181–194. The types of the species belonging to the fusulinid genera Schubertella and Eoschubertella were examined from publica− tions and type collections. Eoschubertella in general possesses all the features of Schubertella and therefore is a junior synonym of the latter. However, the concept of Eoschubertella best describes the genus Schubertina with its type species Schubertina curculi. Schubertina is closely related to the newly established genus Grovesella the concept of which is emended in this paper. Besides Schubertella, Schubertina, and Grovesella, the genera Mesoschubertella, Biwaella are re− viewed and three new species, Grovesella nevadensis, Biwaella zhikalyaki, and Biwaella poletaevi, are described. The phylogenetic relationships of all Pennsylvanian–Cisuralian schubertellids are also proposed. Barrel−shaped Grovesella suggested being the very first schubertellid that appears sometimes in the middle–late Bashkirian time. In late Bashkirian it is then developed into ovoid to fusiform Schubertina. The latter genus gave rise into Schubertella in early Moscovian. First Fusiella derived from Schubertella in late Moscovian, Biwaella—in early Gzhelian and Boultonia—in late Gzhelian time. Genus Mesoschubertella also developed from Schubertella at least in Artinskian, but may be in late Sakmarian. -

Permian Fusulinids from Cobachi, Central Sonora, Mexico

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas,Permian v. 19, núm. fusulinids 1, 2002, from p. 25Cobachi,-37 central Sonora 25 Permian fusulinids from Cobachi, central Sonora, Mexico Olivia Pérez-Ramos1* and Merlynd Nestell2 1 Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Sonora Rosales y Transversal, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora 2 Geology Department, University of Texas at Arlington, UTA 76019 *e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Upper Paleozoic rocks in the Cobachi area of central Sonora, Mexico, include the Picacho Colorado and La Vuelta Colorada formation of Carboniferous?-Permian age. A 155 m carbonate succession of the Picacho Colorado Formation, exposed on the east side of Cerro Picacho Colorado, a few kilometers southeast of Cobachi, consists of pinkish and reddish limestone, cherty limestone with some recrystallization, and bioclastic gray limestone. Crinoids, bryozoa, brachiopods and fo- raminifers are present indicating a marine shallow water shelf depositional environment. Well pre- served fusulinaceans occur near the top of the section, but are scarce, partially silicified, and poorly preserved in the middle part and the base of the section. Skinnerella cobachiensis n. sp., Paraskin- nerella cf. P. durhami, Parafusulina P. cf. P. multisepta and three unnamed species of Parafusulina of early Permian (Leonardian) age are described from this succession. The fusulinacean assemblage from this area has affinities with forms found in rocks with similar age in east central California, west Texas, southeast Mexico, and Central and South America Key words: fusulinids, Permian, Cobachi, Sonora, Mexico RESUMEN Las rocas del Paleozoico Superior en el área de Cobachi, Mexico incluyen las formaciones Picacho Colorado y La Vuelta Colorada de edad Carbonífero? Pérmico. -

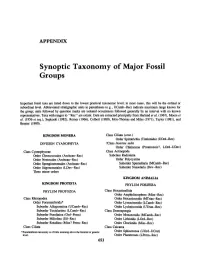

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Late Paleozoic Fossils from Pebbles in the San Cayetano Formation, Sierra Del Rosario, Cuba

Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae (1989). vol. 59: 27-40 PL ISSN 020H-W68 LATE PALEOZOIC FOSSILS FROM PEBBLES IN THE SAN CAYETANO FORMATION, SIERRA DEL ROSARIO, CUBA Andrzej Pszczółkowski Instytut Nauk Geologicznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Al. Żwirki i Wigury 93, 02-089 Warszawa, Poland Pszczółkowski. A., 1989. Late Paleozoic fossils from pebbles in the San Cayetano Formation, Siena del Rosario. Cuba. Ann. Soc. Geol. Polon.. 59: 27 40. Abstract: Late Paleozoic Foraminiferida and Bryozoa have been found in silicified limestone pebbles collected from the sandstones of the San Cayetano Formation in the Sierra del Rosario (western Cuba). All but one specimen of Foraminiferida belong to the Fusulinaeea and include Schwagerina sp. and Parafusulina sp. One specimen of Tetrataxis sp. has been found together with the bryozoan Rhabdomeson sp. The schwagerinids are of Permian (probably Leonardian) age, and the other fossils are of Carboniferous or Permian age. The fossiliferous pebbles were derived from Late Paleozoic rocks located at least some hundred kilometers from the San Cayetano basin during Middle Jurassic to Oxfordian time. The schwagerinid-bearing pebble of Permian age could have been transported from Central America, southwestern North America or northwestern South America (?). Key words: Foraminiferida, Late Paleozoic, Middle-Upper Jurassic, Cuba. Manuscript received February 17, 1988, accepted April 26, 1988 INTRODUCTION In the present paper the first occurrence of Late Paleozoic fossils in Cuba is reported. These fossils were found in pebbles collected from the San Cayetano Formation (Middle Jurassic-Middle Oxfordian) of the Sierra del Rosario in western Cuba (Fig. 1). Besides the characteristics of fossils, this study also deals with the problem of provenance of the fossil-bearing pebbles. -

This Is a Digitised Version of the Original

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/30654/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Glasgow Theses Project: ProQuest: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] FORAMINIFERA OF THE UPPER LIMESTONE GROUP OF THE SCOTTISH CARBONIFEROUS. A. N. Hutton. CONTENTS. VOLUME 1. CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1. Stratigraphy 1* Scope of Collection 7. Acknowledgments. ■ 8. CHAPTER 2. A New Technique for the Study of Smaller Foraminifera in Indurated Limestones. 10. INTRODUCTION 10. PROCEDURE 12. CHAPTER 5. Endothyra. Paramillerella and associated endothyrid and primitive fusulinid foraminifers. 18. MORPHOLOGY 18. The Wall 18. Secondary Deposits 32. Chambers 37. Septa 39. Aperture 40. POPULATION ANALYSIS 41. Explanation of Statistical Symbols 48. CONTENTS - VOLUME 1, CHAPTER 3» - cont. SYSTEMATIC S 65. Sub order Fusulinina 76. Superfamily Endothyracea 76. Family Endothyridea 78. Subfamily Endothyrinae 79. Genus Endothyra 79. Endothyra nhrissa (D.N. Zeller) 95. Endothyra barbata sp. nov. 100. Endothyra nandorae (D.N. Zeller) 103. Endothyra naucinodosa sp. -

Biostratigraphy of the Akiyoshi Limestone Group, Southwest Japan

Bull. Kitakyusku Mus. Nat. Hist., 16: 1-97. March 28, 1997 Middle Carboniferous and Lower Permian Fusulinacean Biostratigraphy of the Akiyoshi Limestone Group, Southwest Japan. Part I Yasuhiro Ota Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Kyushu University33, Hakozaki, Fukuoka 812,Japan (Received October 31, 1996) Abstract The Akiyoshi Limestone Group, oneof the most representative stratigraphic standards ofJapanese Carboniferous and Permian, is widely distributedin the Akiyoshi Terrane, Southwest Japan. TheJigoku-dani area, the main area for investigation, is located in the northwestern part of the Akiyoshi Plateau, where the Middle Carboniferous and Lower Permian limestones are widely exposed. They are mainly composed of micritic limestones, indicating a lagoonal facies, in the relatively low energy environments within the Akiyoshi organicreefcomplex. The limestones are alsocharacterized by abundant and well-preserved fusulinaccans, and the following nine zones including seven subzones, were recognized in ascending order as: 1. Fusulinella biconica Zone, 2. Fusulina cf. shikokuensis Zone: 2-1. Fusulinella cf. obesa Subzone, 2-2. Pseudofusulitulla hidaensis Subzone, 3. Obsoletes obsolelus Zone: 3-1. Protriticites toriyamai Subzone, 3-2. Protriticites matsumotoi Subzone, 4. Montiparus sp. A Zone, 5. Triticites yayamadakensis Zone: 5-1. Triticites saurini Subzone, 5-2. Schwagerina sp. A Subzone, 5-3. Triticites biconicus Subzone, 6. Schwagerina (?) cf. satoi Zone, 7. Pseudoschwagerina muongthensis Zone, 8. Pseudqfusulina vulgaris globosa Zone, 9. Pseudofusulina afi". ambigua Zone. The distribution of these fusulinacean zones shows well the inverted structure of limestones in this area. The second investigated AK area is located in front of the Akiyoshi-dai Museum of Natural History, where limestones with nearly complete successions of the Middle Carboniferous to Lower Permian are well exposed. -

Redalyc.Permian Fusulinids from Cobachi, Central Sonora, Mexico

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas ISSN: 1026-8774 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Pérez Ramos, Olivia; Nestell, Merlynd Permian fusulinids from Cobachi, central Sonora, Mexico Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, vol. 19, núm. 1, 2002, pp. 25-37 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Querétaro, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57219103 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas,Permian v. 19, núm. fusulinids 1, 2002, from p. 25Cobachi,-37 central Sonora 25 Permian fusulinids from Cobachi, central Sonora, Mexico Olivia Pérez-Ramos1* and Merlynd Nestell2 1 Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Sonora Rosales y Transversal, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora 2 Geology Department, University of Texas at Arlington, UTA 76019 *e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Upper Paleozoic rocks in the Cobachi area of central Sonora, Mexico, include the Picacho Colorado and La Vuelta Colorada formation of Carboniferous?-Permian age. A 155 m carbonate succession of the Picacho Colorado Formation, exposed on the east side of Cerro Picacho Colorado, a few kilometers southeast of Cobachi, consists of pinkish and reddish limestone, cherty limestone with some recrystallization, and bioclastic gray limestone. Crinoids, bryozoa, brachiopods and fo- raminifers are present indicating a marine shallow water shelf depositional environment. Well pre- served fusulinaceans occur near the top of the section, but are scarce, partially silicified, and poorly preserved in the middle part and the base of the section. -

Parafusulina (Permian Fusulinacea) from Hazegatoge, Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka Prefecture,Japan

Bull. Kitakyushu Mus. Nat. Hist., 19: 25-42, pis. 1-4. March 31, 2000 Parafusulina (Permian Fusulinacea) from Hazegatoge, Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka Prefecture,Japan Yasuhiro Ota Kitakyushu Museum and Institute of Natural History, Nishihon-machi 3, Yahatahigashi-ku, Kitakyushu 805-0061, JAPAN (Received November 25, 1999) Abstract Well-preserved Permian fusulinacean species are present in conglomerates within the Dobaru Formation, the stratigraphically lowest part of the Early Cretaceous Wakino Subgroup. Three species of Parafusulina (Permian Fusulinacea), Parafusulina cf. kaerimizensis (Ozawa), Parafusulina sp. A, and Parafusulina sp. B, are described and illustrated. These fusulinaceans in clasts of non-crystalline limestone reworked into Early Cretaceous conglomerates indicate that the limestone source was close to the sedimentary basin of the Dobaru Formation. Introduction Fusulinacean localities are scarce in Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan, and seldom yield well-preserved specimens, even though the Yobuno Group (M. Ota el al., 1992), one of the Carboniferous to Permian groups in the Akiyoshi Terrane, crops out widely there. Most limestones in the Yobuno Group generally are crystalline, as are other limestones of the Hirao Limestone Plateau, and sparsely contain fossils. Fusulinaceans were first reported by Yabe (1920) from limestone within the Otsumi Units (Nakae, 1997), and this was later confirmed by Fujimoto el al. (1961). The Early Cretaceous Wakino Subgroup also crops out widely in Kitakyushu City. This subgroup represents the lower part of the Kanmon Group and is divided into four formations, based on the biostratigraphic study of M. Ota and Yabumoto (1998). These formations are the Dobaru, Takatsuo, Gamo and Kumagai Formations, in ascending order. -

Sedimentology, Biostratigraphy and Mineralogy of the Lercara Formation (Triassic, Sicily) and Its Palaeogeographic Implications

UNIVERSITE DE GENEVE FACULTE DES SCIENCES Département de Géologie et Paléontologie Docteur R. Martini Sedimentology, Biostratigraphy and Mineralogy of the Lercara Formation (Triassic, Sicily) and its palaeogeographic implications THESE présentée à la Faculté des sciences de l’Université de Genève pour obtenir le grade de Docteur ès sciences, mention Sciences de la Terre par Lucia CAR C IONE de Longi (Italie) Thèse N° 3841 GENEVE Atelier de reproduction de la Section de Physique 2007 ai miei genitori, Lina e Pippo, con affetto. iii ABSTR A CT This thesis contributes to the resolution of one of the most controversial open questions about Sicilian geology: the age of the Lercara Formation. During the last century, it was variously attributed to the Permian, the Triassic, the Paleogene or the Miocene. A part from the question of the age, this work analyses the palaeoenvironmental context associated to the Lercara Formation deposition and the palaeogeographical evolution of the occidental part of the Tethys during the Permian and the Triassic. The study integrates sedimentological, biostratigraphic and mineralogical analyses, and proposes the reconstitution of the Sicanian basin subsidence history. The Lercara Formation deposited at the bottom of the Sicanian basin and constitutes the oldest formation cropping out in the Siculo-Maghrebian belts chain. It outcrops in western Sicily in the Roccapalumba- Lercara and Margana-Valle Riena areas, near Palazzo Adriano where it is better known as “Fiume Sosio deposits”, and in Portella Rossa near the village of Burgio. For this study, every known outcrop has been sampled, along with a new outcrop located in Portella Rossa. This field did not permit the recognition of any stratigraphic contact with the underlying formation or the basement, nor with the overlying Mufara Formation. -

University of Texas at Arlington Dissertation Template

MICROFAUNAL ASSEMBLAGES OF THE PLACID SHALE (MISSOURIAN, UPPER PENNSYLVANIAN), BRAZOS RIVER VALLEY, NORTH-CENTRAL TEXAS by BRITTANY E. MEAGHER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN GEOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2012 Copyright © by Brittany Meagher 2012 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my granddad Pope Meagher who as a geologist instilled in me, at a young age, my love for rocks. I don’t believe I would have gotten as far without this early love he planted and nurtured to grow within me. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people that I would like to thank for their guidance and patience throughout this thesis project. Without these people, this thesis would not have been possible. I would like to thank Dr. Merlynd Nestell, Committee Chairman, for suggesting this project to me. His advice and assistance throughout this research project has helped me learn as much as possible about various types of microfauna. His review and editing of this manuscript is greatly appreciated. Dr. Galina Nestell, thesis committee member, for teaching me exactly what goes into taxonomically describing a microfossil. Her expertise on the identification of foraminifers contributed to the completion of this thesis. Dr. John Wickham, thesis committee member, for his guiding and teaching me various topics throughout my time at University of Texas Arlington. His time, in both reviewing this manuscript and serving on my committee, is invaluable and greatly appreciated. -

Taxonomy, Nomenclature, and Evolution of the Early Schubertellid Fusulinids

Taxonomy, nomenclature, and evolution of the early schubertellid fusulinids VLADIMIR I. DAVYDOV Davydov, V.I. 2011. Taxonomy, nomenclature, and evolution of the early schubertellid fusulinids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56 (1): 181–194. The types of the species belonging to the fusulinid genera Schubertella and Eoschubertella were examined from publica− tions and type collections. Eoschubertella in general possesses all the features of Schubertella and therefore is a junior synonym of the latter. However, the concept of Eoschubertella best describes the genus Schubertina with its type species Schubertina curculi. Schubertina is closely related to the newly established genus Grovesella the concept of which is emended in this paper. Besides Schubertella, Schubertina, and Grovesella, the genera Mesoschubertella, Biwaella are re− viewed and three new species, Grovesella nevadensis, Biwaella zhikalyaki, and Biwaella poletaevi, are described. The phylogenetic relationships of all Pennsylvanian–Cisuralian schubertellids are also proposed. Barrel−shaped Grovesella suggested being the very first schubertellid that appears sometimes in the middle–late Bashkirian time. In late Bashkirian it is then developed into ovoid to fusiform Schubertina. The latter genus gave rise into Schubertella in early Moscovian. First Fusiella derived from Schubertella in late Moscovian, Biwaella—in early Gzhelian and Boultonia—in late Gzhelian time. Genus Mesoschubertella also developed from Schubertella at least in Artinskian, but may be in late Sakmarian. Key words: -

University of Nevada Reno Fusulinid Paleontology And

University of Nevada Reno Fusulinid Paleontology and Paleoecology of Eastern Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology by Robert Bruce Cline June 1967 &oS7*9 mines Tk<? s f-s (72 < L . X The thesis of Robert Bruce Cline is approved: Dean> Graduate School University of Nevada Reno ! June 1967 ABSTRACT Paleontological and paleoecological studies in White Pine and Eureka Counties, Nevada, revealed 24 fusulinid taxa. The optimum environment for fusulinids appears to have been shallow (10-50 m), light-penetrated, marine waters of about 35 ppm salinity. The schwagennids and triticitids are more numerous in the limestones containing about 20 per cent terrigenous materials. The parafusu- linids show a wide tolerance of impurities by species, but more individuals occur in the purer limestones. The smaller fusulinids appear not to be restricted by environment. I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .......... ii LIST OF TABLES . iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS v INTRODUCTION . , 1 Location and Accessibility • ; Climate and Vegetation ; ; ; Industry of the Area . ; Purpose and Scope . ; ; Method of Investigation ' ; . Previous Work Acknowledgments .......... GEOLOGICAL SETTING Stratigraphy Structure SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY General Statement Systematic Descriptions^ Discussions, and Occurrences ........ THE SEDIMENTS The Energy Index Classification ' ; , Carbonate Types ..... ........ PALEOECOLOGY ........ ..... PALEOECOLOGY AND FACIES .... BIBLIOGRAPHY ..... ........ APPENDIX A — GLOSSARY ...... APPENDIX B--PHOTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUE iii LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Carbonate Classification .......... 2. A Key to Figures 3 and 5 .......... 3. Sediments of Studied Areas ........ 4. Table of Measurements ....... iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figiire Page 1. Location .................................... 2 2. Alvaolfnella and Pseudofusulina compared ......... 48 3. Fusulinid distribution .................................. 55 4.